Chapter 7 Self-help strategies

Aims and sources

Some of the biomechanical self-help approaches in this chapter are derived from a series of copyright-free articles by Craig Liebenson DC (2001) that were written for the Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, entitled ‘Self-help for the clinician’ and ‘Self-help for the patient’. The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr Liebenson’s far-sighted contribution to the field of rehabilitation, with earnest appreciation. Other strategies, designed for patient use, that have been included in this chapter are summarized from the text Multidisciplinary Approaches to Breathing Pattern Disorders (Chaitow et al 2002) of which one of the authors of this text (LC) is a co-author. Grateful thanks are due to the other authors, Dinah Bradley Morrison PT (1998) and Chris Gilbert PhD (2002).

Coherence, compliance and concordance

Gilbert (2002) provides insights into what is a very real problem for anyone trying to encourage a patient to modify habitual patterns of use, whether this relates to posture, breathing or other activities. Gilbert’s focus is on breathing, which, as he points out, has its own unique dynamics.

In Volume 1, second edition, Chapter 8 (pages 173 and 174 in particular – see also Fig. 8.3 in that chapter) rehabilitation and compliance issues are discussed. An abbreviated summary of some of the key elements of that discussion is included in Box 7.1 of this text.

Box 7.1 Summary of rehabilitation and compliance issues from Volume 1, Chapter 8

Psychosocial factors in pain management: the cognitive dimension

Liebenson (1996) states:

Motivating patients to share responsibility for their recovery from pain or injury is challenging. Skeptics insist that patient compliance with self-treatment protocols is poor and therefore should not even be attempted. However, in chronic pain disorders, where an exact cause of symptoms can only be identified 15% of the time, the patient’s participation in their treatment program is absolutely essential (Waddell 1998). Specific activity modification advice aimed at reducing exposure to repetitive strain is one aspect of patient education (Waddell et al 1996). Another includes training in specific exercises to perform to stabilize a frequently painful area (Liebenson 1996, Richardson & Jull 1995). Patients who feel they have no control over their symptoms are at greater risk of developing chronic pain (Kendall et al 1997). Teaching patients what they can do for themselves is an essential part of caring for the person who is suffering with pain. Converting a pain patient from a passive recipient of care to an active partner in their own rehabilitation involves a paradigm shift from seeing the doctor as healer to seeing him or her as helper (Waddell et al 1996).

Guidelines for pain management (Bradley 1996)

• Assist the person in altering beliefs that the problem is unmanageable and beyond his control.

• Inform the person about the condition.

• Assist the person in moving from a passive to an active role.

• Enable the person to become an active problem solver and to develop effective ways of responding to pain, emotion and the environment.

• Help the person to monitor thoughts, emotions and behaviors and to identify how internal and external events influence these.

• Give the person a feeling of competence in the execution of positive strategies.

• Help the person to develop a positive attitude to exercise and personal health management.

• Help the person to develop a program of paced activity to reduce the effects of physical deconditioning.

• Assist the person in developing coping strategies that can be continued and expanded once contact with the pain management team or health-care provider has ended.

Barriers to progress in pain management (Gil et al 1988, Keefe et al 1996)

• Litigation and compensation issues, which may act as a deterrent to compliance.

• Distorted perceptions about the nature of the problem.

• Beliefs based on previous diagnosis and treatment failure.

• Lack of hope created by practitioners whose prognosis was limiting (‘Learn to live with it’).

• Dysfunctional beliefs about pain and activity.

• Negative expectation about the future.

• Lack of awareness of the potential for (self) control of the condition.

Goal setting and pacing (Bucklew 1994, Gil et al 1988)

Rehabilitation goals should be set in three separate fields.

• Physical – the number of exercises to be performed, or the duration of the exercise, and the level of difficulty.

• Functional tasks – this relates to the achievement of functional tasks of everyday living.

• Social – where goals are set relating to the performance of activities in the wider social environment. These should be personally relevant, interesting, measurable and, above all, achievable.

Low back pain rehabilitation

In regard to rehabilitation from painful musculoskeletal dysfunction. Liebenson (1996, 2007) maintains:

• train awareness of postural (neutral range joint) control during activities

• prescribe beginner (‘no brainer’) exercises

• facilitate automatic activity in ‘intrinsic’ muscles by reflex stimulation

• progress to more challenging exercises (i.e. labile surfaces, whole-body exercises)

• transition to activity-specific exercises

Concordance

Compliance, adherence and participation are extremely poor regarding exercise programs (as well as other health enhancement self-help programs), even when the individuals felt that the effort was producing benefits. Research indicates that most rehabilitation programs report a reduction in participation in exercise (Lewthwaite 1990, Prochaska & Marcus 1994). Wigers et al (1996) found that 73% of patients failed to continue an exercise program when followed up, although 83% felt they would have been better if they had done so. Participation in exercise is more likely if the individual finds it interesting and rewarding.

Research into patient participation in their recovery program in fibromyalgia settings has noted that a key element is that whatever is advised (exercise, self-treatment, dietary change, etc.) needs to make sense to the individual, in his own terms, and that this requires consideration of cultural, ethnic and educational factors (Burckhardt 1994, Martin 1996). In general, most experts, including Lewit (1992), Liebenson (2007) and Lederman (1997), highlight the need (in treatment and rehabilitation of dysfunction) to move as rapidly as possible from passive (operator-controlled) to active (patient-controlled) methods. The rate at which this happens depends largely on the degree of progress, pain reduction and functional improvement.

• Why is this being suggested?

• What evidence is there of benefit?

• What reactions might be expected?

• What should I do if there is a reaction?

• Can I call or contact you if I feel unwell after exercise (or other self-applied treatment)?

Background information for the clinician will mainly be found in Chapter 6, although in some instances there are brief introductory notes for the clinician in this chapter as well.

What we can learn from research into compliance

In the 2nd edition of Rehabilitation of the Spine, Liebenson (2007) embraces a remarkable shift to a new patient-centered model of management of spine disorders. ‘Rather than focusing merely on pathology and symptoms, the emphasis is on recovery, reactivation, and self-management. Passive care approaches utilizing medication, modalities, and manipulation are being replaced with an active self-care paradigm.’ He provides overwhelming evidence in support of these concepts along with the ‘reasons why a traditional biomedical way of thinking is far from ideal for a multifactorial problem such as spine pain.’

Åsenlöf et al (2009) examined the long-term effects of a Tailored Behavioural Treatment (TBT) protocol, compared with an Exercise Based Physical Therapy (EBPT) protocol. Compliance and outcomes were far better in the TBT group. One interesting outcome, apart from the compliance issue, was that fear of movement/(re)injury increased in the EBPT-group, but not the TBT group.

The key elements of TBT are summarized as follows:

• Identify goals for daily activity – create a priority list of goals

• Select a first goal to target based on an activity in everyday-life – this could be almost anything that is relevant to the patient, for example, a particular distance to be able to walk pain free.

• Identify physical activity of the person’s own choice, as well as intermediate objectives.

• There should be discussion of hypothesized physical, cognitive, behavioral, and psychosocial features that relate to the pain or dysfunction

• The skills required to achieve the goals that have been chosen should be identified and basic exercises practiced, particularly as these relate to everyday-life situations.

• As initial gains are made, additional goals on the priority list should be identified and prioritized to extend the application of acquired skills to new activities and situations

• Maintenance and relapse prevention, involving strategies for maintenance of new skills, should be incorporated.

Howard & Gosling (2008) found that patients who have a positive attitude, more education and more previous positive experiences in relation to health, sport and exercise are more likely to be compliant to practitioner prescribed exercise rehabilitation programs. They also found that personal characteristics – such as attitude, education and past experience relating to health, sport and exercise – need to be assessed prior to exercise prescription. Gaining an early insight into whether a patient is likely to be ‘compliant’ or ‘non-compliant’ can provide practitioners a basis upon which to design their rehabilitation processes.

Biomechanical self-help methods

Positional release self-help methods (for tight, painful muscles and trigger points) (Chaitow 2006)

But how are we to know in which direction to move tissues that are very painful and tense? There are some very simple rules and we can use these on ourselves in an easy-to-apply ‘experiment’. Now, perform the steps in Box 7.2.

Box 7.2 Patient self-help. PRT exercise (Chaitow 2007)

• Sit in a chair and, using a finger, search around in the muscles of the side of your neck, just behind your jaw, directly below your ear lobe about an inch. Most of us have painful muscles here. Find a place that is sensitive to pressure.

• Press just hard enough to hurt a little and grade this pain for yourself as a ‘10’ (where 0 = no pain at all). However, do not make it highly painful; the 10 is simply a score you assign.

• While still pressing the point bend your neck forward, very slowly, so that your chin moves toward your chest.

• Keep deciding what the ‘score’ is in the painful point.

• As soon as you feel it ease a little start turning your head a little toward the side of the pain, until the pain drops some more.

• By ‘fine tuning’ your head position, with a little turning, sidebending or bending forward some more, you should be able to get the score close to ‘0’ or at least to a ‘3’.

• When you find that position you have taken the pain point to its ‘position of ease’ and if you were to stay in that position (you don’t have to keep pressing the point) for up to a minute and a half, when you slowly return to sitting up straight the painful area should be less sensitive and the area will have been flushed with fresh oxygenated blood.

• If this were truly a painful area and not an ‘experimental’ one, the pain would ease over the next day or so and the local tissues would become more relaxed.

• You can do this to any pain point anywhere on the body, including a trigger point, which is a local area that is painful on pressure and that also refers a pain to an area some distance away or that radiates pain while being pressed. It may not cure the problem (sometimes it will) but it usually offers ease.

The rules for self-application of PRT are as follows.

• Locate a painful point and press just hard enough to score ‘10’.

• If the point is on the front of the body, bend forward to ease it and the further it is from the mid-line of your body, the more you should ease yourself toward that side (by slowly sidebending or rotating).

• If the point is on the back of the body ease slightly backward until the ‘score’ drops a little and then turn away from the side of the pain, and then ‘fine tune’ to achieve ease.

• Hold the ‘position of ease’ for not less than 30 seconds (up to 90 seconds) and very slowly return to the neutral starting position.

• Make sure that no pain is being produced elsewhere when you are fine tuning to find the position of ease.

• Do not treat more than five pain points on any one day as your body will need to adapt to these self-treatments.

• Expect improvement in function (ease of movement) fairly soon (minutes) after such self-treatment but reduction in pain may take a day or so and you may actually feel a little stiff or achy in the previously painful area the next day. This will soon pass.

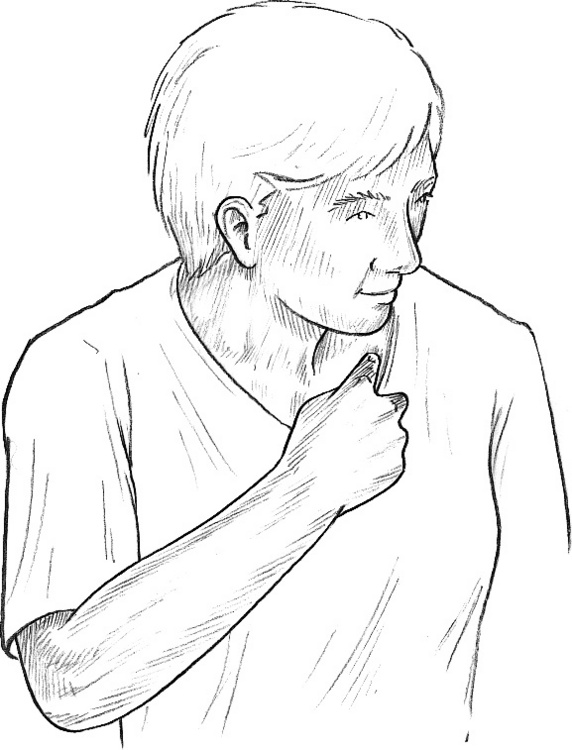

• If intercostal muscle (between the ribs) tender points are being self-treated, in order to ease feelings of tightness or discomfort in the chest, breathing should be felt to be easier and less constricted after PRT self-treatment. Tender points to help release ribs are often found either very close to the sternum (breast bone) or between the ribs, either in line with the nipple (for the upper ribs) or in line with the front of the axilla (armpit) (for ribs lower than the 4th) (Fig. 7.1).

• If you follow these instructions carefully, creating no new pain when finding your positions of ease and not pressing too hard, you cannot harm yourself and might release tense, tight and painful muscles.

Figure 7.1 Positional release self-treatment for an upper rib tender point

(reproduced from Chaitow 2000).

Muscle energy self-help methods (for tight, painful muscles and trigger points)

In this sort of exercise light contractions only are used, involving no more than a quarter of your available strength. Now, practice the steps in Box 7.3.

Box 7.3 Patient self-help. MET neck relaxation exercise (Chaitow 2004)

Phase 1

• Sit close to a table with your elbows on the table and rest your hands on each side of your face.

• Turn your head as far as you can comfortably turn it in one direction, say to the right, letting your hands move with your face, until you reach your pain-free limit of rotation in that direction.

• Now use your left hand to resist as you try to turn your head back toward the left, using no more than a quarter of your strength and not allowing the head to actually move. Start the turn slowly, building up force which is matched by your resisting left hand, still using 25% or less of your strength.

• Hold this push, with no movement at all taking place, for about 7–10 seconds and then slowly stop trying to turn your head left.

• Now turn your head round to the right as far as is comfortable.

• You should find that you can turn a good deal further than the first time you tried, before the isometric contraction. You have been using MET to achieve what is called postisometric relaxation in tight muscles that were restricting you.

Phase 2

• Your head should be turned as far as is comfortable to the right and both your hands should still be on the sides of your face.

• Now use your right hand to resist your attempt to turn (using only 25% of strength again) even further to the right starting slowly, and maintaining the turn and the resistance for a full 7–10 seconds.

• If you feel any pain you may be using too much strength and should reduce the contraction effort to a level where no pain at all is experienced.

• When your effort slowly stops see if you can now go even further to the right than after your first two efforts. You have been using MET to achieve a different sort of release called reciprocal inhibition.

Exercises for spinal flexibility

The four exercises described below (one flexion – Box 7.4, one extension – Box 7.5 and two rotation – Box 7.6) as well as those in Box 7.7, will help maintain flexibility or help to restore it if the spine is stiff. They should not be done if they cause any pain. Do these in sequence every day to maintain suppleness. The exercises described are designed to safely restore and maintain this flexibility

• If it hurts to perform any of the described exercises or you are in pain after their use, stop doing them. Either they are unsuitable for your particular condition or you are performing them incorrectly, too energetically or excessively.

• Remember that these exercises are prevention exercises, meant to be performed in a sequence so that all the natural movements of the spine can benefit, and are not designed for treatment of existing back problems.

Box 7.4 Patient self-help. Prevention: flexion exercise (Chaitow 2004)

Perform daily but not after a meal.

• Sit on the floor with both legs straight out in front of you, toes pointing toward the ceiling. Bend forward as far as is comfortable and grasp one leg with each hand.

• Hold this position for about 30 seconds – approximately four slow deep breathing cycles. You should be aware of a stretch on the back of the legs and the back. Be sure to let your head hang down and relax into the stretch. You should feel no actual pain and there should be no feeling of strain.

• As you release the fourth breath ease yourself a little further down the legs and grasp again. Stay here for a further half minute or so before slowly returning to an upright position, which may need to be assisted by a light supporting push upward by the hands.

• Bend one leg and place the sole of that foot against the inside of the other knee, with the bent knee lying as close to the floor as possible.

• Stretch forward down the straight leg and grasp it with both hands. Hold for 30 seconds as before (while breathing in a similar manner) and then, on an exhalation, stretch further down the leg and hold for a further 30 seconds (while continuing to breathe).

• Slowly return to an upright position and alter the legs so that the straight one is now bent, and the bent one straight. Perform the same sequence as described above.

• Perform the same sequence with which you started, with both legs out straight.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree