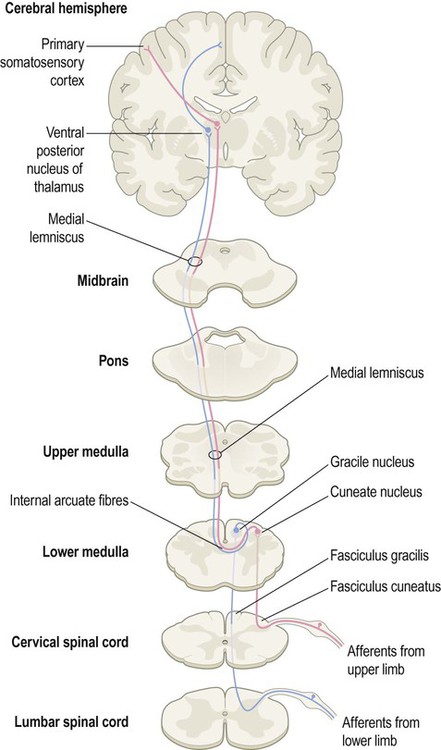

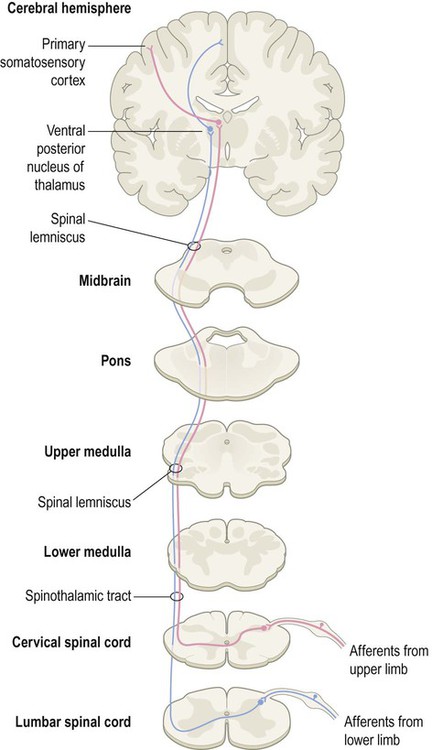

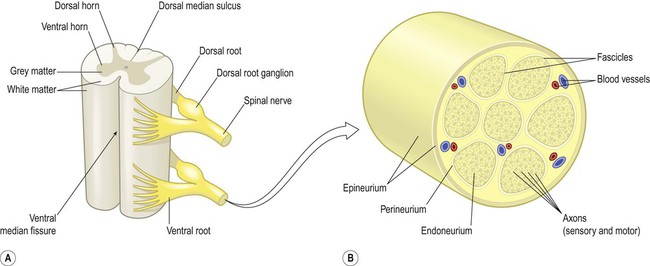

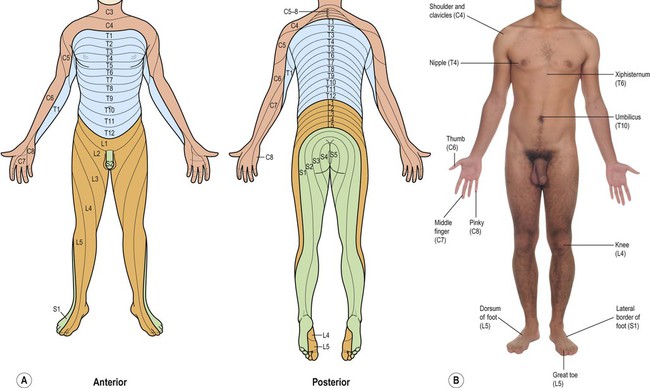

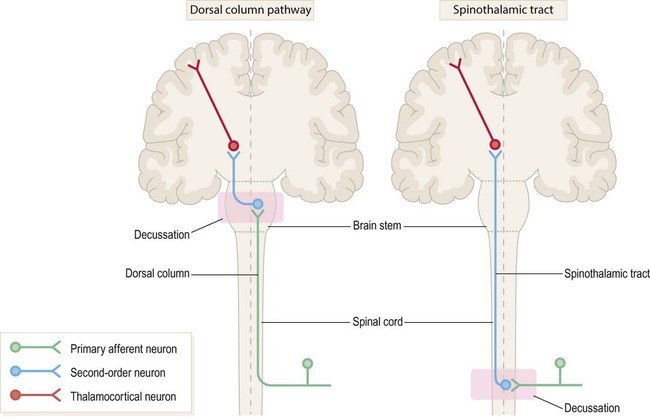

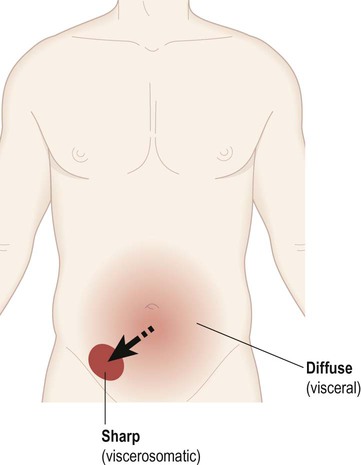

The spinal cord is divided into 31 segments (Fig. 4.1A), each with a pair of dorsal (sensory) roots and a pair of ventral (motor) roots. The dorsal and ventral roots unite on each side to form a mixed spinal nerve (spinal nerve root) (Fig. 4.1B). Each nerve root divides into a small dorsal ramus, which supplies the paravertebral muscles and provides cutaneous sensation to the back, and a large ventral ramus which innervates the limbs and trunk. The dorsal root ganglia at each spinal level contain the cell bodies of sensory neurons that innervate an area of skin called a dermatome (Fig. 4.2). They also contain the cell bodies of sensory neurons innervating muscles, tendons, ligaments and joints. Two major spinal cord pathways carry sensory information to the cerebral cortex where it can be consciously perceived. The dorsal column pathway is concerned with precisely localized touch and joint position sense. The spinothalamic tract is primarily responsible for pain and temperature sensation. Each pathway is composed of a three-neuron chain with a similar arrangement (Fig. 4.3): The dorsal column pathway is mainly responsible for precisely localized touch and proprioception (awareness of one’s own body; Latin: proprius, one’s own) including joint position sense. It contains large myelinated axons (A-alpha fibres) which transmit impulses at speeds of up to 120 metres per second. Integrity of the dorsal columns is best assessed clinically using a tuning fork (Clinical Box 4.1). The spinothalamic tract mediates pain and temperature sensations. Impulses are transmitted by small-diameter unmyelinated c-fibres and thinly-myelinated A-delta fibres which conduct impulses at relatively slow speeds of 0.5–15 metres per second. This pathway can be tested clinically using a sterile pin (Clinical Box 4.2). Some spinothalamic axons contribute to a spinoreticular pathway which synapses in the reticular formation of the brain stem. From here, reticulothalamic fibres ascend to the intralaminar nuclei of the thalamus before projecting on to the limbic lobe and insula, which have visceral and emotional roles including pain perception (Clinical Box 4.3). Visceral pain is diffuse, poorly localized and centred on the midline. It is often associated with autonomic features such as sweating, nausea, vomiting and pallor. In contrast, viscerosomatic pain is sharp and well-localized. It occurs when inflammatory exudate from a diseased organ makes contact with a somatic (body-wall) structure such as the parietal peritoneum. Abdominal pathology (e.g. appendicitis) may therefore present with diffuse visceral pain, before progressing to sharp viscerosomatic pain (Fig. 4.6).

Sensory and motor pathways

Spinal segments

(A) Schematic illustrating two spinal cord segments; (B) A spinal nerve root shown in transverse section. The nerve root consists of sensory and motor axons arranged in bundles (fascicles) surrounded by connective tissue (endoneurium, perineurium, epineurium) and blood vessels. Modified from Fitzgerald: Clinical Neuroanatomy and Neuroscience 5e (2006) with permission.

(A) Illustration of the complete dermatome map from anterior and posterior aspects, with the spinal root values indicated; (B) Photograph showing a number of key dermatome levels that it is clinically-useful to be familiar with.

Somatic sensory pathways

The first-, second- and third-order neurons are coloured green, blue and red respectively. Note that in both pathways the second-order neuron has its cell body in the central nervous system (CNS) and gives rise to an axon that crosses the midline and ascends to the thalamus. The main difference between the two pathways is the location of the second neuron (which in turn determines where each pathway crosses the midline).

The first-order neurons have their cell bodies in the dorsal root ganglia, each with one process that contributes to a peripheral nerve and another that enters the spinal cord.

The first-order neurons have their cell bodies in the dorsal root ganglia, each with one process that contributes to a peripheral nerve and another that enters the spinal cord.

The second-order neurons have their cell bodies in the grey matter of the brain stem or spinal cord and give rise to axons that cross the midline, before ascending to the thalamus.

The second-order neurons have their cell bodies in the grey matter of the brain stem or spinal cord and give rise to axons that cross the midline, before ascending to the thalamus.

The third-order neurons are located in the ventral posterior (VP) nucleus of the thalamus and project to the primary somatosensory cortex, via the posterior limb of the internal capsule (see Ch. 3).

The third-order neurons are located in the ventral posterior (VP) nucleus of the thalamus and project to the primary somatosensory cortex, via the posterior limb of the internal capsule (see Ch. 3).

Dorsal column pathway

Spinothalamic tract

The spinoreticulothalamic pathway

Pain arising from the internal organs

Visceral and viscerosomatic pain

In the early stages of appendicitis the patient typically describes a dull, nauseating, poorly localized (visceral) pain centred on the umbilicus. As the inflammation spreads to involve the abdominal wall, a sharp (viscerosomatic) pain arises in the lower right quadrant of the abdomen, corresponding to the position of the appendix.![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Sensory and motor pathways

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue