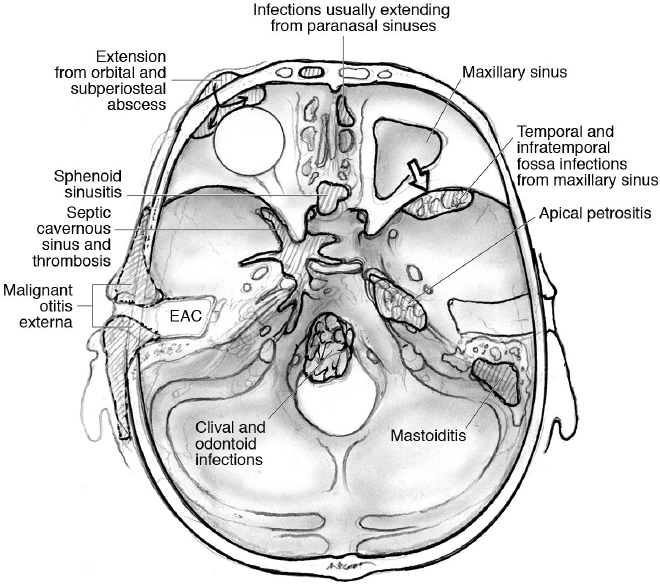

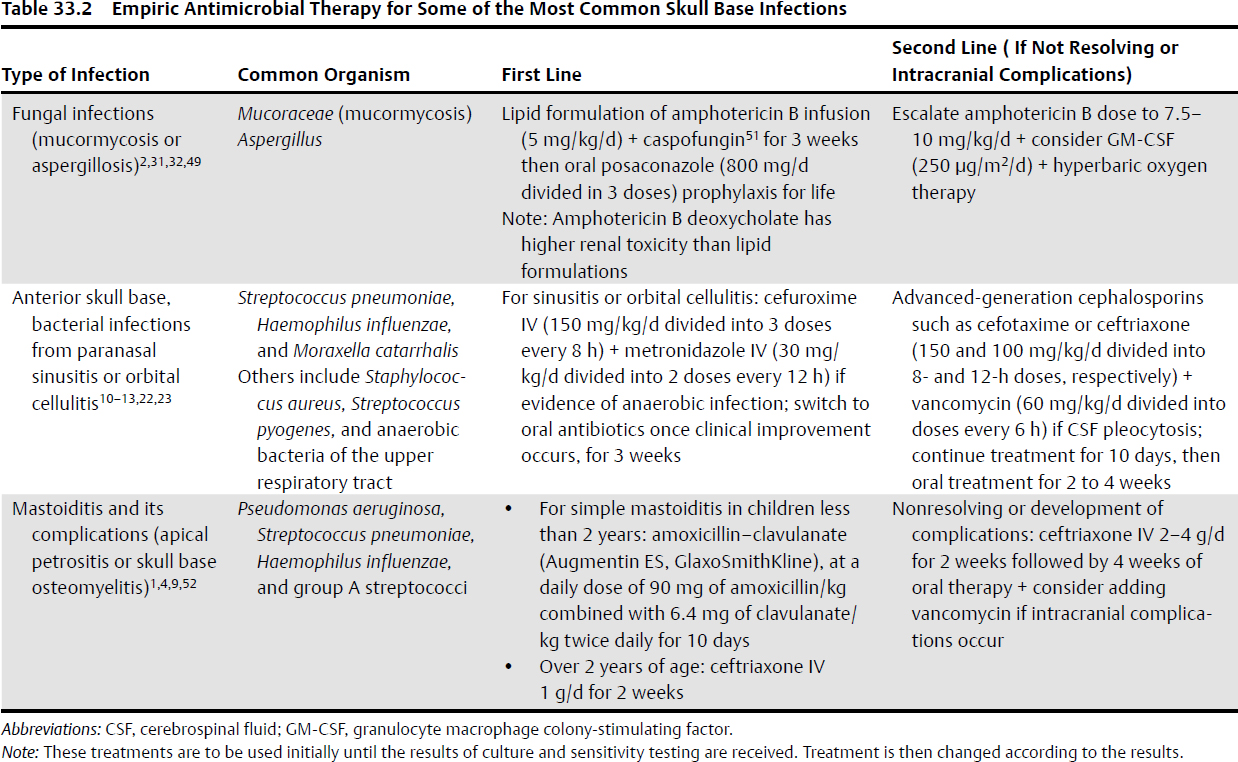

33 Skull Base Infections With the introduction and use of antibiotics over the past century, infections of the skull base have become rare, especially in the Western countries.1 These serious conditions occur most often in predisposed patient populations, including diabetic, elderly, or immunocompromised individuals,2–11 making their management difficult (Table 33.1). The most common skull base infections, according to location, are illustrated in Fig. 33.1. • Osteomyelitis with, or without, bony erosion and destruction • Mass lesions, e.g., subperiosteal abscesses or fungal masses • Basal meningitis • Cerebritis Sinusitis affects an estimated 16% of the adult population in the United States.12 Intracranial complications of paranasal sinusitis include subdural empyema, brain abscess, meningitis, subperiosteal abscess, and osteomyelitis of the anterior skull base.13–15 Infection spreads in susceptible individuals to the anterior cranial base and orbit through either direct extension (from the nose, ethmoid, sphenoid, or frontal air sinuses) or retrograde thrombophlebitis.13 Although bacterial and viral infections are more common in sinusitis, they are usually noninvasive and thus are infrequently associated with a skull base infection.12 The only exception is posttraumatic sinusitis with pyocele formation, ultimately leading to subperiosteal abscess, brain abscess, osteomyelitis, and bony destruction.13,14 This condition is most commonly seen in frontal sinus penetrating injuries. Fungal infections tend to be more invasive. Invasive fungal sinusitis most commonly starts in the nose or paranasal sinuses, then extends to the orbit, with the destruction of the cribriform plate or orbital apex, and to the cranial base, causing mass effect on intracranial structures.2 The most common pathogens for invasive fungal sinusitis are Mucoraceae (mucormycosis) followed by Aspergillus2 (Table 33.2). Mortality from invasive fungal sinusitis in immunocompromised patients is 50 to 90%. Table 33.1 Precipitating Factors of the Most Common Skull Base Infections, and Patients Affected2–11

Infections of the Anterior Skull Base

Infections of the Anterior Skull Base

Extension from Paranasal Sinus Infections

Pathophysiology

General | Diabetes Old age Trauma Surgery Immunocompromised CNS infections causing basal arachnoiditis (e.g., cysticercosis) |

Specific |

|

• Paranasal sinus infection | Pediatrics and young adults |

• Orbital infections | Pediatrics |

• Osteomyelitis | Trauma, surgery |

• Malignant otitis externa | Old age, DM |

• Mastoiditis | Pediatrics, immunocompromised |

• Fungal infections | DM, AIDS, immunocompromised |

• Odontoid infections | Old age, immunocompromised |

• Apical petrositis | Middle ear infections |

Abbreviations: AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; CNS, central nervous system; DM, diabetes mellitus.

Clinical Presentation and Sequelae

Presentation often occurs in childhood or young adulthood, and the condition is usually precipitated by trauma, diabetes mellitus (DM), or immunocompromised states, such as corticosteroids therapy, malignancies, burns, AIDS, or renal failure.16 Fever and other constitutional manifestations are usually absent in fungal and chronic sinus infections. The most common presentations are as follows2,11–16:

• History of trauma or recurrent sinusitis.

• Local pain, swelling, and redness over the affected sinus. Frontal sinusitis can cause a Pott’s puffy tumor, which is swelling and edema over the eyebrow due to subperiosteal abscess formation, and is usually associated with frontal bone osteomyelitis.17 This was originally described with a tuberculous subperiosteal abscess.

• Focal neurologic manifestations or symptoms of increased intracranial pressure from intracranial mass effect (e.g., fungal mass).

• Mass lesions from mucormycosis can extend to involve the temporal and infratemporal fossae.

• Ophthalmoplegia, proptosis, or blindness from extension to the orbit or cavernous sinus thrombosis (see Box 33.1).

• Other intracranial complications of paranasal sinusitis include basal meningitis, cavernous sinus thrombosis, subdural empyema, and brain abscess. Approximately half of subdural empyema and parenchymal brain abscesses are caused by paranasal sinusitis.

Workup12,18

• Laboratory:

Leukocytosis is nonspecific, but may denote acute infection, with elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) (nonspecific and elevated in many inflammatory and infectious conditions).

Leukocytosis is nonspecific, but may denote acute infection, with elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) (nonspecific and elevated in many inflammatory and infectious conditions).

Neutropenia can occur with fungal infections.

Neutropenia can occur with fungal infections.

Culture and sensitivity analysis of the sinus aspiration.

Culture and sensitivity analysis of the sinus aspiration.

Blood cultures are usually sterile. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) cultures may be indicated in selected patients, but, because of the potential presence of mass effects, should be considered only after imaging is completed.

Blood cultures are usually sterile. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) cultures may be indicated in selected patients, but, because of the potential presence of mass effects, should be considered only after imaging is completed.

Box 33.1. Cavernous Sinus Thrombosis21–25

Septic cavernous sinus thrombosis is a serious complication of acute sinusitis and orbital and midface infections in an otherwise healthy individual. Infection usually spreads directly through the valveless ophthalmic veins. In the pre-antibiotic era, mortality was almost 100%, but with antimicrobial agents it is now less than 30%.

The clinical presentation is usually acute, and includes the following:

1. Retro-orbital pain is usually the first sign. It is followed by periorbital edema and ecchymosis.

2. Ophthalmoplegia (abducens nerve is affected first).

3. Exophthalmos.

4. Increased intraocular pressure.

5. Sluggish papillary responses and decreased visual acuity.

6. Extension to the contralateral eye is suggestive.

7. Meningeal signs.

8. Subarachnoid hemorrhage or carotid occlusion can occur with fungal infections.

Imaging studies include CT and MRI with contrast, supplemented by magnetic resonance venography (MRV), magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) and diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (DW-MRI). Common findings with imaging are as follows:

1. Filling defects within the cavernous sinus with contrast injection indicating thrombi

2. Widening of the cavernous sinus evident by its walls turning convex instead of concave

3. Absence of flow signals and restricted diffusion, especially in superior ophthalmic veins

4. Dilation of cavernous sinus tributaries

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for detection of circulating DNA from mucorales.19,20

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for detection of circulating DNA from mucorales.19,20

• Imaging: computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain, orbit, and paranasal sinuses

Opacification of the paranasal sinuses or air–fluid level

Opacification of the paranasal sinuses or air–fluid level

Mucosal thickening or enhancement within the sinus

Mucosal thickening or enhancement within the sinus

Orbital cellulitis (see below)

Orbital cellulitis (see below)

CT to assess bony destruction within the anterior cranial base and its extent

CT to assess bony destruction within the anterior cranial base and its extent

Herniation of the brain through cranial base defects, into orbits or ethmoid

Herniation of the brain through cranial base defects, into orbits or ethmoid

Subperiosteal abscess, subdural empyema, or intracranial mass lesions

Subperiosteal abscess, subdural empyema, or intracranial mass lesions

Cavernous sinus thrombosis (see Box 33.1)

Cavernous sinus thrombosis (see Box 33.1)

• D-dimer testing

A recent study suggested that D-dimer testing may be useful in diagnosing cavernous sinus thrombosis.24

A recent study suggested that D-dimer testing may be useful in diagnosing cavernous sinus thrombosis.24

Extension from Orbital Cellulitis

Pathophysiology

Orbital cellulitis is an orbital infection commonly seen in the pediatric age group following (1) direct spread from ethmoid, maxillary, or sphenoid sinusitis; (2) traumatic inoculation; or (3) hematogenous spread from nasopharyngeal pathogens.7,15,26 The usual causative organisms are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis, as well as others7 (Table 33.2). Orbital cellulitis can be associated with subperiosteal abscess formation and osteomyelitis. Infection can spread through the roof of the orbit to the anterior base, causing anterior skull base osteomyelitis and bony destruction.27 Septic thrombosis of the ophthalmic veins can result in cavernous sinus thrombosis.7,28

Clinical Presentation and Sequelae7,27,28

Presentation usually occurs in childhood, or, less commonly, young adulthood, and usually consists of one or more of the following:

• Fever, headache, and malaise

• Orbital pain, swelling, and ecchymosis

• Ophthalmoplegia and proptosis from cavernous sinus thrombosis, subperiosteal abscess, or rarely herniation of the brain through the osteomyelitic orbital roof

• Enophthalmos, if the roof of the maxillary sinus (floor of the orbit) is destroyed

• Progression to blindness

Workup7,21,29

• Laboratory

Complete blood count may reveal leukocytosis, with elevated ESR and CRP.

Complete blood count may reveal leukocytosis, with elevated ESR and CRP.

Blood cultures reveals an organism in 30 to 60% of the cases.

Blood cultures reveals an organism in 30 to 60% of the cases.

CSF cultures are usually negative, but may show pleocytosis.

CSF cultures are usually negative, but may show pleocytosis.

Cultures and sensitivity analysis of aspirate from the affected sinus or percutaneously from the orbital subperiosteal abscess.

Cultures and sensitivity analysis of aspirate from the affected sinus or percutaneously from the orbital subperiosteal abscess.

• Imaging: CT and MRI of the brain, orbit and paranasal sinuses. Intracranial and paranasal sinuses as described above for paranasal sinusitis; orbital findings include the following:

Edema of the orbital contents (best seen on T2) and proptosis

Edema of the orbital contents (best seen on T2) and proptosis

Differentiation among subperiosteal abscess, orbital abscess, and cellulitis

Differentiation among subperiosteal abscess, orbital abscess, and cellulitis

Thrombosis of the superior ophthalmic veins: engorged superior ophthalmic vein (best seen on T2 coronal to differentiate from rectus muscle); DW-MRI shows restricted diffusion within the vessel22,23

Thrombosis of the superior ophthalmic veins: engorged superior ophthalmic vein (best seen on T2 coronal to differentiate from rectus muscle); DW-MRI shows restricted diffusion within the vessel22,23

Infections of the Middle and Posterior Skull Base

Infections of the Middle and Posterior Skull Base

Sphenoid Sinusitis

Pathophysiology

Isolated sphenoid sinus infections are the rarest form of paranasal sinus infections and account for roughly 2.5% of all sinus infections. Commonly, sphenoidal sinus infections follow initial infections of another group of paranasal sinuses.30 As with other paranasal sinuses, the infection could be viral, bacterial, or fungal (Table 33.2). More than 60% of cases of isolated sphenoid sinusitis, especially the invasive type, are fungal. Aspergillus is the most common species.31 Invasive fungal sinusitis usually occurs in immunocompromised individuals, although case reports of isolated and invasive disease in immunocompetent patients have been described.32 Due to close proximity of the sphenoid sinus to the cavernous sinus, invasive fungal sinusitis can spread to the cavernous sinus through afferent communicating veins or directly through osteomyelitis of the sphenoid bone or bony defects within the sphenoid sinus walls.30

Classically, Aspergillus hyphae proliferate within the sinus. Necrosis and deposition of calcium crystals follows with mucopurulent discharge.30,31 Some authors refer to the fungal mass inside the sphenoid as a “fungal ball or a mycetoma.”31

Clinical Presentation and Sequelae30–33

The most common presentations of isolated sphenoid sinusitis are headache, retro-orbital pain, and purulent rhinorrhea. Constitutional manifestations are rarely present. Sphenoid sinusitis produces very few localizing symptoms, and thus is difficult to diagnose by routine clinical and radiological examination. Consequently, sphenoid sinusitis is frequently misdiagnosed on presentation; patients are referred initially to clinicians other than otolaryngologists, and the condition is suspected only after the development of complications.

Possible sequelae of the disease include the following:

• Osteomyelitis and destruction of the sphenoid bone

• Extension to other paranasal sinuses

• Extension to the orbit

• Cavernous sinus thrombosis, infection, or compression by mucocele or fungal balls (also with eventual invasion of the internal carotid artery [ICA] by Aspergillus)

• Meningitis and brain abscess

• Extension to a pneumatized anterior clinoid through the optic strut, eventually compressing the optic nerve33

Workup30,31

Workup and imaging findings for sphenoid sinus infections are similar to those of other paranasal sinus infections described above. Fungal sinusitis, however, have some pathognomonic features:

• Laboratory

Culture or pathology the sphenoid sinus contents during endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) can reveal the fungal hyphae.

Culture or pathology the sphenoid sinus contents during endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) can reveal the fungal hyphae.

Blood: elevated ESR and CRP, sometimes with neutropenia and eosinophilia. Culture is often negative.

Blood: elevated ESR and CRP, sometimes with neutropenia and eosinophilia. Culture is often negative.

• Imaging

CT usually shows central hyperdense areas of calcification (calcium crystals) and areas of bone destruction, if invasive.

CT usually shows central hyperdense areas of calcification (calcium crystals) and areas of bone destruction, if invasive.

MRI can assess intracranial and intraorbital complications, such as cavernous sinus thrombosis, meningitis, and others. Of particular note, fungal elements are typically hypodense on T2-weighted images.

MRI can assess intracranial and intraorbital complications, such as cavernous sinus thrombosis, meningitis, and others. Of particular note, fungal elements are typically hypodense on T2-weighted images.

Sphenoid Wing, Temporal, and Infratemporal Fossa Infections

• Usually an extension of mucormycosis or maxillary sinus infections.

Mastoiditis

Pathophysiology

Acute mastoiditis is a serious complication of acute otitis media (AOM). It is more common in the pediatric age group, as most patients are younger than 4 years of age.4 AOM extends through the aditus to the mastoid antrum into mastoid air cells, and inflammation of mastoid epithelium blocks adequate drainage, facilitating the propagation of the infection.3 There are two stages for the disease: stage 1, which is mastoiditis with periostitis, and stage 2, termed acute coalescent mastoiditis. The most common organisms causing the infection are Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and group A Streptococcus.34 With progression, especially in immunocompromised individuals, the disease could extend to the surrounding areas of the cranial base with development of malignant otitis externa, also known as skull base osteomyelitis35 (see Box 33.2).

Box 33.2. Malignant Otitis Externa (Skull Base Osteomyelitis)35,37,38

A serious osteomyelitis of the temporal bone and skull base usually follows otitis externa, or less commonly otitis media, in elderly patients. One of the hallmarks of this progression is granulation tissue in the bone–cartilage junction of the external auditory canal. With the exception of a few case reports, the causative organism is Pseudomonas and the condition is usually facilitated by impaired host immunity. There is usually a history of otitis externa or acute otitis media with the following superimposed:

• Severe otalgia and ear discharge, not responding to medical treatment.

• Severe headache.

• Cranial nerve deficits due to secretion of neurotoxins or the compressive effect of the destructive process through the relevant foramina. The facial nerve is usually the first nerve affected, followed by lower cranial nerve palsies in advanced cases.

• Late osteomyelitis can spread to other skull base locations, such as the sphenoid bone or infratemporal fossa.

• Central nervous system (CNS) complications (see Mastoiditis. above).

In addition to the clinical picture, diagnosis can be made by any of the following:

• Pathological examination of granulation tissue in the external auditory canal.

• CT scan of the petrous bone and skull base in order to assess the extent of disease and bone destruction.

• MRI of the brain is useful for detecting intracranial complications.

• CT bone scan and gallium scans are positive with skull base osteomyelitis. Gallium scan assesses mainly soft tissue disease. Both can also be used to monitor the response to treatment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree