10

SLEEP-RELATED MOVEMENT DISORDERS

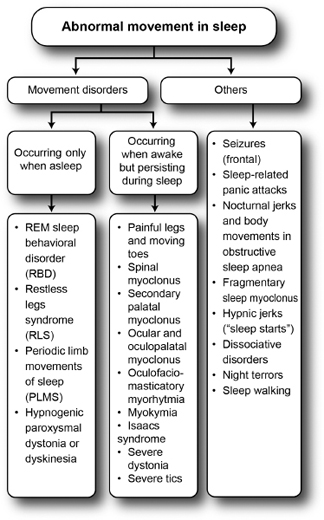

Although most movement disorders typically disappear during sleep, some persist, and some even occur almost exclusively while the patient is asleep or falling asleep. Movement disorders that occur during sleep should be distinguished from mimickers (Figure 10.1).1,2

MOVEMENT DISORDERS THAT OCCUR ONLY DURING SLEEP/FALLING ASLEEP AND DISAPPEAR DURING WAKEFULNESS

REM Sleep Behavioral Disorder (RSBD)

Sleep with rapid eye movements (REM sleep) is the stage of sleep in which dreaming occurs. It is associated with ocular movements and atonia of the other somatic muscles.

Sleep with rapid eye movements (REM sleep) is the stage of sleep in which dreaming occurs. It is associated with ocular movements and atonia of the other somatic muscles.

In RSBD, muscle atonia is absent, thereby enabling the patient to unwarily “act out his or her dreams.”

In RSBD, muscle atonia is absent, thereby enabling the patient to unwarily “act out his or her dreams.”

The patient can wake up and injure himself or herself or, more commonly, a bed partner.

The patient can wake up and injure himself or herself or, more commonly, a bed partner.

Polysomnography (PSG) showing excessive chin muscle tone and limb jerking during REM sleep is needed for a definitive diagnosis.3

Polysomnography (PSG) showing excessive chin muscle tone and limb jerking during REM sleep is needed for a definitive diagnosis.3

RSBD may precede by several years a synucleinopathy (eg, Parkinson’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, or multiple systems atrophy), and its presence in a middle-aged man implies a 52.4% risk for the development of Parkinson’s disease or dementia at 12 years.4

RSBD may precede by several years a synucleinopathy (eg, Parkinson’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, or multiple systems atrophy), and its presence in a middle-aged man implies a 52.4% risk for the development of Parkinson’s disease or dementia at 12 years.4

Medications commonly associated with RSBD are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and tricyclic antidepressants.5

Medications commonly associated with RSBD are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and tricyclic antidepressants.5

Figure 10.1

Differential diagnosis of abnormal movement in sleep.

Source: From Refs. 1, 2.

Treatment may not be necessary if symptoms are mild or intermittent, but it will be needed if the behavior is violent and dangerous for either the patient or the bed partner.

Treatment may not be necessary if symptoms are mild or intermittent, but it will be needed if the behavior is violent and dangerous for either the patient or the bed partner.

Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS)

RLS is now considered the most frequent movement disorder.2

RLS is now considered the most frequent movement disorder.2

It is characterized by a deep, ill-defined sensation of discomfort or dysesthesia in the legs that arises during prolonged rest or when the patient is drowsy and trying to fall asleep (Table 10.1).7 Wayne Hening coined the acronym URGE as a convenient reminder of the key features of RLS (Table 10.2).8

It is characterized by a deep, ill-defined sensation of discomfort or dysesthesia in the legs that arises during prolonged rest or when the patient is drowsy and trying to fall asleep (Table 10.1).7 Wayne Hening coined the acronym URGE as a convenient reminder of the key features of RLS (Table 10.2).8

Table 10.1

Essential Diagnostic Criteria for Restless Legs Syndrome

1 | An urge to move the legs, usually accompanied or caused by uncomfortable and unpleasant sensations in the legs. (Sometimes the arms or other body parts are involved in addition to the legs.) |

2 | The urge to move or unpleasant sensations begin or worsen during periods of rest or inactivity such as lying or sitting. |

3 | The urge to move or unpleasant sensations are partially or totally relieved by movement, such as walking or stretching, at least as long as the activity continues. |

4 | The urge to move or unpleasant sensations are worse in the evening or night than during the day or only occur in the evening or night. (When symptoms are very severe, the worsening at night may not be noticeable but must have been previously present.) |

Source: From Ref. 7: Allen RP, Picchietti D, Hening WA, Trenkwalder C, et al; Restless Legs Syndrome Diagnosis and Epidemiology workshop at the National Institutes of Health; International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group. Restless legs syndrome: diagnostic criteria, special considerations, and epidemiology. A report from the restless legs syndrome diagnosis and epidemiology workshop at the National Institutes of Health. Sleep Med. 2003; 4(2):101–119.

Table 10.2

The URGE Acronym for Restless Legs Syndrome

U: Urge to move the legs, usually associated with unpleasant leg sensations.

R: Rest induces symptoms.

G: Getting active (physically and mentally) brings relief.

E: Evening and night make symptoms worse.

Supportive clinical features of RLS include a family history and a good initial response to low doses of levodopa or a dopamine receptor agonist.

Supportive clinical features of RLS include a family history and a good initial response to low doses of levodopa or a dopamine receptor agonist.

The physical examination is generally normal and does not contribute to the diagnosis, except for comorbid conditions or causes of secondary RLS.

The physical examination is generally normal and does not contribute to the diagnosis, except for comorbid conditions or causes of secondary RLS.

RLS is generally a condition of middle to old age, but at least one-third of patients experience their first symptoms before the age of 20. If the patient is older than 50 years at symptom onset, the symptoms often develop abruptly and severely, whereas if the patient is younger than 50 years, the onset is often more insidious. Symptoms usually worsen with age.8

RLS is generally a condition of middle to old age, but at least one-third of patients experience their first symptoms before the age of 20. If the patient is older than 50 years at symptom onset, the symptoms often develop abruptly and severely, whereas if the patient is younger than 50 years, the onset is often more insidious. Symptoms usually worsen with age.8

The prevalence of RLS among the first-degree relatives of people with RLS is 3 to 5 times greater than the prevalence in people without RLS. An autosomal dominant genetic transmission is suspected, but no single causal gene has been identified.

The prevalence of RLS among the first-degree relatives of people with RLS is 3 to 5 times greater than the prevalence in people without RLS. An autosomal dominant genetic transmission is suspected, but no single causal gene has been identified.

Periodic limb movements in sleep (PLMS) occur in 85% of patients with RLS. The clinical spectrum may also include myoclonic jerks, more sustained dystonic movements, or stereotypic movements that occur while the patient is awake.2

Periodic limb movements in sleep (PLMS) occur in 85% of patients with RLS. The clinical spectrum may also include myoclonic jerks, more sustained dystonic movements, or stereotypic movements that occur while the patient is awake.2

RLS can be divided into primary and secondary forms.

RLS can be divided into primary and secondary forms.

Primary RLS is idiopathic and frequently familial, and it starts at a younger age.

Primary RLS is idiopathic and frequently familial, and it starts at a younger age.

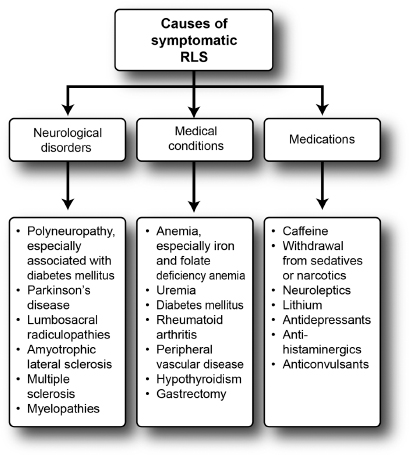

Secondary, or symptomatic, RLS is associated with iron deficiency anemia, pregnancy, or end-stage renal disease, and also with chronic myelopathies, peripheral neuropathies, gastric surgery, chronic lung disease, and some drugs (Figure 10.2).

Secondary, or symptomatic, RLS is associated with iron deficiency anemia, pregnancy, or end-stage renal disease, and also with chronic myelopathies, peripheral neuropathies, gastric surgery, chronic lung disease, and some drugs (Figure 10.2).

The diagnosis of RLS is clinical. PSG is not necessary. The differences between RLS and akathisia are listed in Table 10.3. RLS must also be distinguished from the syndrome of painful legs and moving toes (see below).

The diagnosis of RLS is clinical. PSG is not necessary. The differences between RLS and akathisia are listed in Table 10.3. RLS must also be distinguished from the syndrome of painful legs and moving toes (see below).

The treatment of secondary RLS requires addressing its cause (stopping the offending medication, correcting iron deficiency, treating uremia, etc).

The treatment of secondary RLS requires addressing its cause (stopping the offending medication, correcting iron deficiency, treating uremia, etc).

Dopamine agonists are the first-line pharmacotherapy. They are associated with less risk for augmentation (defined as an increase in the severity of symptoms, a shift in the time when symptoms start to earlier in the day, a shorter latency to the start of symptoms during rest, and sometimes the spread of symptoms to other body parts) than levodopa, which is also effective.2,8

Dopamine agonists are the first-line pharmacotherapy. They are associated with less risk for augmentation (defined as an increase in the severity of symptoms, a shift in the time when symptoms start to earlier in the day, a shorter latency to the start of symptoms during rest, and sometimes the spread of symptoms to other body parts) than levodopa, which is also effective.2,8

Gabapentin and gabapentin enacarbil are second-line therapy and can be especially beneficial in cases of painful RLS.9,10

Gabapentin and gabapentin enacarbil are second-line therapy and can be especially beneficial in cases of painful RLS.9,10

Figure 10.2

Causes of symptomatic restless legs syndrome.

Source: From Ref. 1: Bhidayasiri R. Movement disorders. In: Bhidayasiri R, Waters MF, Giza C, eds. Neurological Differential Diagnosis: A Prioritized Approach. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2005: 203–239.

A recent study found pregabalin to be beneficial with less risk of augmentation than pramipexole.11

A recent study found pregabalin to be beneficial with less risk of augmentation than pramipexole.11

Opiates and benzodiazepines can be used as third-line therapy.

Opiates and benzodiazepines can be used as third-line therapy.

The off-label use of an antiepileptic drug, such as topiramate, can be considered in cases of refractory RLS, especially if it is painful.12

The off-label use of an antiepileptic drug, such as topiramate, can be considered in cases of refractory RLS, especially if it is painful.12

Iron infusion must be reserved for severe cases unresponsive to other therapies and associated with low plasma levels of ferritin. A high-dose intravenous infusion of iron dextran (1,000 mg) or iron sucrose (5 infusions of 200 mg each over 3 weeks) can be used, the former being more effective but carrying a higher risk for anaphylactic shock. Patients receiving ferritin should be monitored closely during therapy to avoid hemochromatosis. Oral iron does not seem to be effective except to correct an iron deficiency anemia.7

Iron infusion must be reserved for severe cases unresponsive to other therapies and associated with low plasma levels of ferritin. A high-dose intravenous infusion of iron dextran (1,000 mg) or iron sucrose (5 infusions of 200 mg each over 3 weeks) can be used, the former being more effective but carrying a higher risk for anaphylactic shock. Patients receiving ferritin should be monitored closely during therapy to avoid hemochromatosis. Oral iron does not seem to be effective except to correct an iron deficiency anemia.7

Table 10.3

Restless Legs Syndrome Versus Akathisia

Features | Restless Legs Syndrome | Akathisia |

Definition | See Tables 10.1 and 10.2. | Inner restlessness, fidgetiness with jittery feeling, or generalized restlessness |

Occurs as a side effect of neuroleptics | Less common | More common |

Disease course | Chronic and progressive | Can be acute, chronic, or tardive |

Character of restlessness | Tossing, turning in bed, floor pacing, leg stretching, leg flexion, foot rubbing, need to get up and walk | Swaying and rocking movements, crossing and uncrossing the legs, shifting body positions, inability to sit still; resembles mild chorea |

Schedule | Mostly in the evening or at night | Mostly during the day |

Worsening factor | Inactivity or rest. | Anxiety or stress |

Alleviating factor | Moving the legs, walking | Moving around, walking |

Source: Adapted from Ref. 1: Bhidayasiri R. Movement disorders. In: Bhidayasiri R, Waters MF, Giza C, eds. Neurological Differential Diagnosis: A Prioritized Approach. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2005:203–239.

Periodic Limb Movements of Sleep (PLMS) (Table 10.4)

PLMS can affect one or both legs.

PLMS can affect one or both legs.

Movements are brief (1–2 seconds).

Movements are brief (1–2 seconds).

Dorsiflexion of big toe and foot.

Dorsiflexion of big toe and foot.

Flexion of hip and knee also possible. The movement then resembles a flexion reflex.

Flexion of hip and knee also possible. The movement then resembles a flexion reflex.

Occurs every 20 seconds, for minutes or hours.

Occurs every 20 seconds, for minutes or hours.

Can wake up bed partner and may cause a sleep disturbance in the patient, who then experiences excessive daytime drowsiness.

Can wake up bed partner and may cause a sleep disturbance in the patient, who then experiences excessive daytime drowsiness.

The diagnosis is confirmed by PSG. PLMS usually occurs during stages I and II of sleep and decreases in stages III and IV. Unusual in REM sleep.

The diagnosis is confirmed by PSG. PLMS usually occurs during stages I and II of sleep and decreases in stages III and IV. Unusual in REM sleep.

Occasionally seen in an awake, drowsy patient.2

Occasionally seen in an awake, drowsy patient.2

Although PLMS can be seen alone, RLS occurs in 30% of cases of PLMS.

Although PLMS can be seen alone, RLS occurs in 30% of cases of PLMS.

Table 10.4

Periodic Movements of Sleep

• Brief (lasting 1–2 seconds) jerks in one or both legs

• Occur in runs (every 20 seconds) for minutes to hours

• Initial jerk followed by tonic spasm

• Dorsiflexion of big toe and foot (or flexion of whole leg)

• Occurs during light sleep (stages I and II)

• Occasionally seen in an awake, drowsy patient

• Usually asymptomatic, may wake sleeping partner or, less often, the patient

• Prevalence increases with age: younger than 30 years, rare; 30 to 50 years, 5%; older than 50 years, 29%

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree