18 SPEECH AND SWALLOWING THERAPY Speech and swallowing abnormalities occur frequently in patients with movement disorders. The evaluation and treatment of motor speech disorders (ie, dysarthria and apraxia of speech [AOS]) and of oropharyngeal dysphagia are typically performed by speech–language pathologists. These evaluations and treatments can accomplish the following: This chapter summarizes the procedures that speech–language pathologists use to evaluate speech and swallowing. The Mayo classification system of motor speech disorders is introduced, with an emphasis on its relevance for physicians and other health care providers. Finally, speech and swallowing disorders and their treatment in a variety of movement disorders are discussed. Figure 18.1 Table 18.1 Type Localization Neuromotor Basis Flaccid dysarthria Lower motor neuron Weakness Spastic dysarthria Bilateral upper motor neuron Spasticity Ataxic dysarthria Cerebellar control circuit Incoordination Hypokinetic dysarthria Basal ganglia control circuit Rigidity or reduced range of movements Hyperkinetic dysarthria Basal ganglia control circuit Abnormal movements Mixed dysarthria More than one More than one Apraxia of speech Left (dominant) hemisphere Motor planning and programming Figure 18.2 Figure 18.3

SPEECH AND SWALLOWING ABNORMALITIES ASSOCIATED WITH MOVEMENT DISORDERS

Determine whether speech and swallowing are affected

Determine whether speech and swallowing are affected

Determine the severity of speech and swallowing involvement and the patient’s prognosis

Determine the severity of speech and swallowing involvement and the patient’s prognosis

Assist in the formulation of a treatment plan

Assist in the formulation of a treatment plan

Improve the patient’s functioning and quality of life

Improve the patient’s functioning and quality of life

Assist the medical team in making the differential diagnosis

Assist the medical team in making the differential diagnosis

EVALUATION OF SPEECH

Speech–language pathologists use primarily auditory–perceptual methods to evaluate speech disorders, although the use of instrumental assessment techniques, such as direct laryngoscopy, acoustic analysis of speech, and kinematic measurement, is becoming increasingly common.

Speech–language pathologists use primarily auditory–perceptual methods to evaluate speech disorders, although the use of instrumental assessment techniques, such as direct laryngoscopy, acoustic analysis of speech, and kinematic measurement, is becoming increasingly common.

A traditional clinical motor speech evaluation consists of four components:

A traditional clinical motor speech evaluation consists of four components:

History

History

Examination of the speech mechanism with nonspeech activities

Examination of the speech mechanism with nonspeech activities

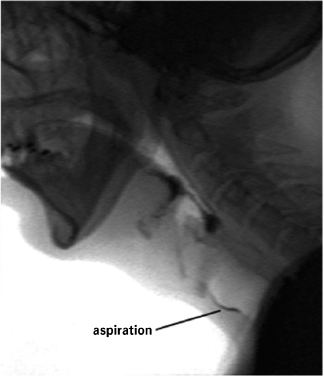

Key components of a traditional clinical motor speech evaluation.

Maximum performance testing of the speech mechanism

Maximum performance testing of the speech mechanism

Evaluation of speech performance during a variety of speaking tasks (See Appendix A for a typical paragraph that a patient is asked to read to evaluate speech.)

Evaluation of speech performance during a variety of speaking tasks (See Appendix A for a typical paragraph that a patient is asked to read to evaluate speech.)

Figure 18.1 reviews the components of typical assessment procedures for speech disorders in greater detail.1–4

Figure 18.1 reviews the components of typical assessment procedures for speech disorders in greater detail.1–4

The Mayo Classification of Speech Disorders

Darley et al5–7 refined the auditory–perceptual method of classifying speech disorders in a series of seminal works. This classification system, now known as the Mayo system, is based on several premises:

Darley et al5–7 refined the auditory–perceptual method of classifying speech disorders in a series of seminal works. This classification system, now known as the Mayo system, is based on several premises:

Speech disorders can be categorized into different types.

Speech disorders can be categorized into different types.

They can be characterized by distinguishable auditory–perceptual characteristics.

They can be characterized by distinguishable auditory–perceptual characteristics.

They have different underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms associated with different neuromotor deficits.

They have different underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms associated with different neuromotor deficits.

Therefore, the Mayo system has value for localizing neurological disease and can assist the medical team in formulating a differential diagnosis.1

Therefore, the Mayo system has value for localizing neurological disease and can assist the medical team in formulating a differential diagnosis.1

The Mayo system also provides guidance for treatment planning.8

The Mayo system also provides guidance for treatment planning.8

Table 18.1 details the types of motor speech disorders, their localization, and their neuromotor basis.

Table 18.1 details the types of motor speech disorders, their localization, and their neuromotor basis.

Types of Motor Speech Disorders With Their Localization and Neuromotor Basis

Behavioral Treatment of Speech Disorders

Most of the approaches to the treatment of speech abnormalities in patients with movement disorders are presented later in this chapter under the sections on specific medical diagnoses. However, regardless of the medical or speech diagnosis, certain therapeutic principles apply:

Most of the approaches to the treatment of speech abnormalities in patients with movement disorders are presented later in this chapter under the sections on specific medical diagnoses. However, regardless of the medical or speech diagnosis, certain therapeutic principles apply:

Treatment should be aimed at maximizing intelligibility and naturalness.

Treatment should be aimed at maximizing intelligibility and naturalness.

For maximum benefit, patients and families must be committed to rehabilitation.

For maximum benefit, patients and families must be committed to rehabilitation.

In many instances, treatment will need to be intensive.

In many instances, treatment will need to be intensive.

For further details regarding the principles of treatment for motor speech disorders, see Rosenbek and Jones.9

For further details regarding the principles of treatment for motor speech disorders, see Rosenbek and Jones.9

EVALUATION OF SWALLOWING

Swallowing function is typically considered to comprise three stages:

Swallowing function is typically considered to comprise three stages:

Oral stage

Oral stage

Pharyngeal stage

Pharyngeal stage

Esophageal stage

Esophageal stage

The assessment and treatment of the oral and pharyngeal stages of swallowing are within the scope of practice of speech–language pathologists as part of an interdisciplinary team that includes physicians, surgeons, occupational therapists, dieticians, nurses, dentists, and other health care professionals. Esophageal dysphagia is managed primarily by physicians (ie, gastroenterologists).

The assessment and treatment of the oral and pharyngeal stages of swallowing are within the scope of practice of speech–language pathologists as part of an interdisciplinary team that includes physicians, surgeons, occupational therapists, dieticians, nurses, dentists, and other health care professionals. Esophageal dysphagia is managed primarily by physicians (ie, gastroenterologists).

The evaluation of oropharyngeal swallowing typically begins with a clinical swallowing evaluation. The traditional components include the following:

The evaluation of oropharyngeal swallowing typically begins with a clinical swallowing evaluation. The traditional components include the following:

History

History

Oral motor examination, often with sensory testing

Oral motor examination, often with sensory testing

Physical examination to assess voice quality and strength of cough, and palpation of laryngeal excursion during swallowing

Physical examination to assess voice quality and strength of cough, and palpation of laryngeal excursion during swallowing

Observation of how foods and liquids are swallowed

Observation of how foods and liquids are swallowed

Instrumental assessment techniques may also be necessary, such as videofluoroscopic swallowing evaluation (VFSE) and/or fiber-optic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES), which allow a skilled clinician to accomplish the following:

Instrumental assessment techniques may also be necessary, such as videofluoroscopic swallowing evaluation (VFSE) and/or fiber-optic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES), which allow a skilled clinician to accomplish the following:

Assess the integrity of the oropharyngeal swallowing mechanism

Assess the integrity of the oropharyngeal swallowing mechanism

Establish the biomechanical abnormalities causing dysphagia

Establish the biomechanical abnormalities causing dysphagia

Make appropriate recommendations with regard to oral intake, therapeutic intervention, and consultations with other health care professionals

Make appropriate recommendations with regard to oral intake, therapeutic intervention, and consultations with other health care professionals

VFSE and FEES also allow the assessment of penetration and aspiration, which are often critical because of their potential negative effects on health.

VFSE and FEES also allow the assessment of penetration and aspiration, which are often critical because of their potential negative effects on health.

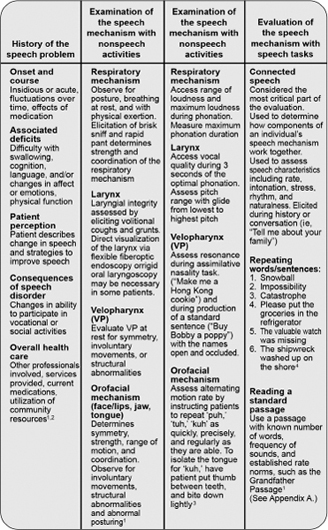

Penetration occurs when material enters the larynx but does not pass into the trachea. Figure 18.2 shows penetration during VFSE.

Penetration occurs when material enters the larynx but does not pass into the trachea. Figure 18.2 shows penetration during VFSE.

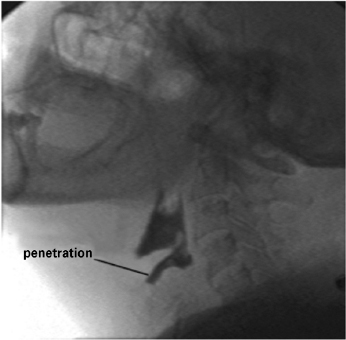

Aspiration occurs when material passes through the larynx and into the trachea. Figure 18.3 shows aspiration during VFSE.

Aspiration occurs when material passes through the larynx and into the trachea. Figure 18.3 shows aspiration during VFSE.

Both aspiration and penetration can be measured during VFSE with the penetration–aspiration scale, an 8-point scale to quantitatively measure the depth of airway entry and whether or not the material is expelled.10

Both aspiration and penetration can be measured during VFSE with the penetration–aspiration scale, an 8-point scale to quantitatively measure the depth of airway entry and whether or not the material is expelled.10

Penetration, or entry of material into the larynx but not the trachea, during videofluoroscopic swallowing evaluation.

Aspiration, or entry of material into the trachea, during videofluoroscopic swallowing evaluation.

Penetration and aspiration can both occur without overt signs and symptoms (ie, coughing, throat clearing, wet vocal quality). This is referred to as silent penetration and silent aspiration.

Penetration and aspiration can both occur without overt signs and symptoms (ie, coughing, throat clearing, wet vocal quality). This is referred to as silent penetration and silent aspiration.

Behavioral Treatment of Swallowing Disorders

Behavioral treatments for dysphagia in patients with movement disorders are based primarily on the biomechanical abnormalities observed during evaluation. Treatments for dysphagia tend to be less condition-specific than those for speech. Therefore, the most common methods are discussed next, and this list is referenced in subsequent sections. Specific treatment approaches with application to particular patient populations follow later in this chapter.

Behavioral treatments for dysphagia in patients with movement disorders are based primarily on the biomechanical abnormalities observed during evaluation. Treatments for dysphagia tend to be less condition-specific than those for speech. Therefore, the most common methods are discussed next, and this list is referenced in subsequent sections. Specific treatment approaches with application to particular patient populations follow later in this chapter.

Regardless of the medical diagnosis, if swallowing (a) remains unsafe, (b) is inadequate to maintain hydration and nutrition, or (c) requires more effort than the patient can tolerate, a variety of behavioral treatments should be considered.

Regardless of the medical diagnosis, if swallowing (a) remains unsafe, (b) is inadequate to maintain hydration and nutrition, or (c) requires more effort than the patient can tolerate, a variety of behavioral treatments should be considered.

Behavioral treatments can be categorized into rehabilitative and compensatory approaches. General behavioral treatments for patients with dysphagia are described below.

Behavioral treatments can be categorized into rehabilitative and compensatory approaches. General behavioral treatments for patients with dysphagia are described below.

Rehabilitative treatments include the following:

Rehabilitative treatments include the following:

Supraglottic swallow is an airway protection technique in which forceful laryngeal adduction is followed by throat clearing/coughing and a repeated swallow.11

Supraglottic swallow is an airway protection technique in which forceful laryngeal adduction is followed by throat clearing/coughing and a repeated swallow.11

Super-supraglottic swallow is airway protection technique similar to the supraglottic swallow, but in which the patient bears down while holding his or her breath.11,12

Super-supraglottic swallow is airway protection technique similar to the supraglottic swallow, but in which the patient bears down while holding his or her breath.11,12

Effortful swallow is used to increase posterior tongue base movement and improve bolus clearance from the vallecula by squeezing the muscles forcefully during swallowing.13

Effortful swallow is used to increase posterior tongue base movement and improve bolus clearance from the vallecula by squeezing the muscles forcefully during swallowing.13

The Mendelsohn maneuver is primarily a technique to prolong upper esophageal sphincter (UES) opening.14 The larynx is held for 1 to 3 seconds in its most anterior–superior position, followed by completion of the swallow.11

The Mendelsohn maneuver is primarily a technique to prolong upper esophageal sphincter (UES) opening.14 The larynx is held for 1 to 3 seconds in its most anterior–superior position, followed by completion of the swallow.11

Shaker head raise is an exercise for increasing UES opening in which the patient lies supine and repetitively raises and lowers his or her head.15,16

Shaker head raise is an exercise for increasing UES opening in which the patient lies supine and repetitively raises and lowers his or her head.15,16

Lee Silverman voice treatment (LSVT) is a series of maximum performance exercises primarily associated with dysarthria rehabilitation. LSVT may also have a general therapeutic effect on swallowing movements.17

Lee Silverman voice treatment (LSVT) is a series of maximum performance exercises primarily associated with dysarthria rehabilitation. LSVT may also have a general therapeutic effect on swallowing movements.17

Expiratory muscle strength training (EMST) is an exercise in which a pressure threshold device is used to overload the muscles of expiration. EMST may have a general therapeutic effect on speech and swallowing movements.18

Expiratory muscle strength training (EMST) is an exercise in which a pressure threshold device is used to overload the muscles of expiration. EMST may have a general therapeutic effect on speech and swallowing movements.18

The Showa maneuver requires forceful elevation of the tongue against the palate followed by a long, hard swallow, during which the patient is instructed to squeeze all the muscles of the face and neck. This technique appears to influence oral and pharyngeal movements during swallowing.

The Showa maneuver requires forceful elevation of the tongue against the palate followed by a long, hard swallow, during which the patient is instructed to squeeze all the muscles of the face and neck. This technique appears to influence oral and pharyngeal movements during swallowing.

The Masako technique is an exercise to increase posterior pharyngeal wall movement. The patient protrudes and holds the tongue while executing a forceful dry swallow.19

The Masako technique is an exercise to increase posterior pharyngeal wall movement. The patient protrudes and holds the tongue while executing a forceful dry swallow.19

In the falsetto exercise, the patient elevates the larynx by sliding up a pitch scale and holding the highest note for several seconds with as much effort as possible.11

In the falsetto exercise, the patient elevates the larynx by sliding up a pitch scale and holding the highest note for several seconds with as much effort as possible.11

Sensory therapies include stimulation with cold, sour, and electrical current. These treatments may improve oral and pharyngeal stage function.21,22

Sensory therapies include stimulation with cold, sour, and electrical current. These treatments may improve oral and pharyngeal stage function.21,22

Intention/attention treatment is a new type of treatment with no formal protocols established.23

Intention/attention treatment is a new type of treatment with no formal protocols established.23

If rehabilitative treatments are unsuccessful or impractical, a variety of compensatory treatments can be considered.

If rehabilitative treatments are unsuccessful or impractical, a variety of compensatory treatments can be considered.

General postural stabilization

General postural stabilization

Postural adjustments to the swallowing mechanism, including the chin tuck and head turn

Postural adjustments to the swallowing mechanism, including the chin tuck and head turn

Throat clearing or coughing to clear the airway after swallowing

Throat clearing or coughing to clear the airway after swallowing

Repeated swallows to clear oropharyngeal residue

Repeated swallows to clear oropharyngeal residue

Use of a “liquid wash” to clear oropharyngeal residue

Use of a “liquid wash” to clear oropharyngeal residue

Controlling bolus size with instruction or adaptive equipment

Controlling bolus size with instruction or adaptive equipment

Increasing the frequency and reducing the size of meals to optimize nutritional intake and swallowing function, especially if swallowing is effortful or causes fatigue

Increasing the frequency and reducing the size of meals to optimize nutritional intake and swallowing function, especially if swallowing is effortful or causes fatigue

Eliminating troublesome foods from the diet or preparing them in a softer, moister form

Eliminating troublesome foods from the diet or preparing them in a softer, moister form

Using dietary supplements

Using dietary supplements

Timing eating and drinking to coincide with maximal medication effects

Timing eating and drinking to coincide with maximal medication effects

Thickening liquids and pureeing foods as a last resort

Thickening liquids and pureeing foods as a last resort

If rehabilitative and compensatory strategies are inadequate, decisions about enteral nutrition may become necessary.

If rehabilitative and compensatory strategies are inadequate, decisions about enteral nutrition may become necessary.

SPEECH AND SWALLOWING IN PARKINSON’S DISEASE

Speech Disorders

Hypokinetic dysarthria occurs in most individuals with Parkinson’s disease (PD) at some point in the progression of the disease, with approximately 90% of patients with PD having dysarthria in some series.24,25 See Appendix B for a description of the perceptual features of hypokinetic dysarthria.

Hypokinetic dysarthria occurs in most individuals with Parkinson’s disease (PD) at some point in the progression of the disease, with approximately 90% of patients with PD having dysarthria in some series.24,25 See Appendix B for a description of the perceptual features of hypokinetic dysarthria.

The term hypophonia is often used to describe the decreased vocal loudness of patients with PD.

The term hypophonia is often used to describe the decreased vocal loudness of patients with PD.

Inappropriate silences may occur frequently and be associated with difficulty initiating movements for speech production.

Inappropriate silences may occur frequently and be associated with difficulty initiating movements for speech production.

Neurogenic stuttering, consisting most often of sound and word repetitions, may also be observed in some patients with PD.

Neurogenic stuttering, consisting most often of sound and word repetitions, may also be observed in some patients with PD.

Patients with PD appear to have a perceptual disconnect between their actual loudness level and their own internal perception of loudness.

Patients with PD appear to have a perceptual disconnect between their actual loudness level and their own internal perception of loudness.

When patients have insight into their speech problem, they often describe the presence of a “weak” voice. They may report avoiding social situations that require speech.

When patients have insight into their speech problem, they often describe the presence of a “weak” voice. They may report avoiding social situations that require speech.

The severity of dysarthria may not correspond to the duration of PD or the severity of other motor symptoms.

The severity of dysarthria may not correspond to the duration of PD or the severity of other motor symptoms.

Hyperkinetic dysarthria, rather than hypokinetic dysarthria, may also be encountered. This most often occurs in the presence of dyskinesia, particularly after prolonged levodopa therapy. Other “communication disorders” commonly encountered in patients with PD include cognitive impairments, masked facies, and micrographia.

Hyperkinetic dysarthria, rather than hypokinetic dysarthria, may also be encountered. This most often occurs in the presence of dyskinesia, particularly after prolonged levodopa therapy. Other “communication disorders” commonly encountered in patients with PD include cognitive impairments, masked facies, and micrographia.

TREATMENT

Although a variety of medical and surgical approaches have been attempted to improve the speech of patients with PD, behavioral treatments have shown the most sustained beneficial effect.26

Although a variety of medical and surgical approaches have been attempted to improve the speech of patients with PD, behavioral treatments have shown the most sustained beneficial effect.26

LSVT has a robust literature supporting its beneficial effects and is considered the treatment of choice for individuals with PD and hypokinetic dysarthria.27–30

LSVT has a robust literature supporting its beneficial effects and is considered the treatment of choice for individuals with PD and hypokinetic dysarthria.27–30

Other maximum performance treatments, such as EMST, may also be beneficial.31

Other maximum performance treatments, such as EMST, may also be beneficial.31

A variety of other behavioral techniques may be indicated.

A variety of other behavioral techniques may be indicated.

Speaker-oriented treatments focus on compensatory strategies to improve intelligibility.32

Speaker-oriented treatments focus on compensatory strategies to improve intelligibility.32

Communication-oriented strategies are often used along with speaker-oriented strategies to improve understanding between speaker and listener.32

Communication-oriented strategies are often used along with speaker-oriented strategies to improve understanding between speaker and listener.32

Rate control techniques, such as delayed auditory feedback (DAF), pitch-shifted feedback, and pacing boards, may be used.

Rate control techniques, such as delayed auditory feedback (DAF), pitch-shifted feedback, and pacing boards, may be used.

For many patients with PD, pharmacologic treatment does not appear to have a significant beneficial impact on speech production, although speech function may be improved in some patients.

For many patients with PD, pharmacologic treatment does not appear to have a significant beneficial impact on speech production, although speech function may be improved in some patients.

Surgical treatments for PD also do not appear to have a consistently significant benefit for the speech disorders encountered in PD. Although speech performance may be improved in some patients after surgery, this is not considered an expected outcome. Speech may be unchanged or worsened following surgery.

Surgical treatments for PD also do not appear to have a consistently significant benefit for the speech disorders encountered in PD. Although speech performance may be improved in some patients after surgery, this is not considered an expected outcome. Speech may be unchanged or worsened following surgery.

Swallowing Disorders

Oropharyngeal dysphagia has been reported in up to 90% to 100% of people with PD. However, dysphagia is often unrecognized or underestimated by patients.33–35

Oropharyngeal dysphagia has been reported in up to 90% to 100% of people with PD. However, dysphagia is often unrecognized or underestimated by patients.33–35

Oropharyngeal dysphagia may be the initial symptom, and a particular pattern of lingual fenestration characterized by repetitive tongue pumping motions is considered a pathognomic sign of PD.11

Oropharyngeal dysphagia may be the initial symptom, and a particular pattern of lingual fenestration characterized by repetitive tongue pumping motions is considered a pathognomic sign of PD.11

The severity of dysphagia may not correspond to the duration of PD or the severity of other motor symptoms.

The severity of dysphagia may not correspond to the duration of PD or the severity of other motor symptoms.

All stages of swallowing function can be affected in patients with PD.

All stages of swallowing function can be affected in patients with PD.

Oral stage deficits may include drooling, increased oral transit time, repetitive tongue pumping motions, and premature spillage of the bolus.

Oral stage deficits may include drooling, increased oral transit time, repetitive tongue pumping motions, and premature spillage of the bolus.

Pharyngeal stage function may be remarkable for a pharyngeal swallow delay, post-swallow pharyngeal residue, penetration, and aspiration.

Pharyngeal stage function may be remarkable for a pharyngeal swallow delay, post-swallow pharyngeal residue, penetration, and aspiration.

Esophageal stage swallowing problems are also common and most frequently include abnormalities in esophageal motility.

Esophageal stage swallowing problems are also common and most frequently include abnormalities in esophageal motility.

TREATMENT

General treatment strategies can be found in the earlier section on the behavioral treatment of swallowing disorders.

General treatment strategies can be found in the earlier section on the behavioral treatment of swallowing disorders.

Patients with PD often respond well to active range-of-motion and falsetto exercises, effortful swallow, Mendelsohn maneuver, and effortful breath-hold.11

Patients with PD often respond well to active range-of-motion and falsetto exercises, effortful swallow, Mendelsohn maneuver, and effortful breath-hold.11

Maximum performance techniques typically used in the rehabilitation of speech disorders in PD, such as LSVT and EMST, may also improve oropharyngeal swallow function.17

Maximum performance techniques typically used in the rehabilitation of speech disorders in PD, such as LSVT and EMST, may also improve oropharyngeal swallow function.17

Although dopaminergic medications are not typically associated with significant improvements in swallow function, in some patients these medications may provide benefit. In these selected cases, “on” effects can be timed to coincide with meals.

Although dopaminergic medications are not typically associated with significant improvements in swallow function, in some patients these medications may provide benefit. In these selected cases, “on” effects can be timed to coincide with meals.

The surgical treatment of PD does not appear to improve swallowing function for most patients, and postoperative dysphagia has been described in the literature as an adverse event.

The surgical treatment of PD does not appear to improve swallowing function for most patients, and postoperative dysphagia has been described in the literature as an adverse event.

Although dysphagia is common in PD, it rarely is severe enough that patients require an alternative means of nutritional support.

Although dysphagia is common in PD, it rarely is severe enough that patients require an alternative means of nutritional support.

SPEECH AND SWALLOWING DISORDERS IN MULTIPLE SYSTEM ATROPHY

Speech Disorders

Dysarthria is a common symptom of multiple system atrophy (MSA) and has been reported in up to 100% of unselected patients in some studies.36

Dysarthria is a common symptom of multiple system atrophy (MSA) and has been reported in up to 100% of unselected patients in some studies.36

Dysarthria in MSA is usually more severe than in PD and often emerges earlier in the course of the disease.1

Dysarthria in MSA is usually more severe than in PD and often emerges earlier in the course of the disease.1

Because of the involvement of multiple brain systems in MSA, the presentation of dysarthria can be expected to be heterogeneous and complex.

Because of the involvement of multiple brain systems in MSA, the presentation of dysarthria can be expected to be heterogeneous and complex.

A mixed dysarthria with features of hypokinetic, ataxic, and spastic types of dysarthria is described most frequently in patients with MSA.1 See Appendix B for a description of the perceptual features of these dysarthria types.1

A mixed dysarthria with features of hypokinetic, ataxic, and spastic types of dysarthria is described most frequently in patients with MSA.1 See Appendix B for a description of the perceptual features of these dysarthria types.1

In patients with prominent features of parkinsonism (ie, MSA-P subtype), features of hypokinetic dysarthria may be expected to predominate.

In patients with prominent features of parkinsonism (ie, MSA-P subtype), features of hypokinetic dysarthria may be expected to predominate.

In patients with prominent features of cerebellar dysfunction (ie, MSA-C subtype), features of ataxic dysarthria may be most notable.

In patients with prominent features of cerebellar dysfunction (ie, MSA-C subtype), features of ataxic dysarthria may be most notable.

In patients with prominent features of autonomic failure and ataxia, hypokinetic, and/or spastic dysarthria, alone or in combination, have been described.37

In patients with prominent features of autonomic failure and ataxia, hypokinetic, and/or spastic dysarthria, alone or in combination, have been described.37

Stridor may occur in patients with MSA. This may result in respiratory ataxia and even necessitate a tracheostomy in severe cases. Stridor in MSA has usually been attributed to vocal cord paralysis, but some data suggest that the cause is laryngeal–pharyngeal dystonia.36

Stridor may occur in patients with MSA. This may result in respiratory ataxia and even necessitate a tracheostomy in severe cases. Stridor in MSA has usually been attributed to vocal cord paralysis, but some data suggest that the cause is laryngeal–pharyngeal dystonia.36

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree