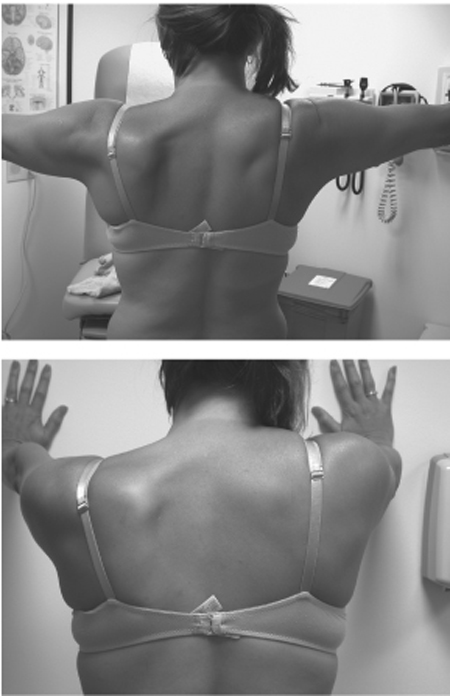

15 Spinal Accessory Nerve Palsy A 17-year-old, right-handed woman in previously good health went to her family physician for evaluation of “glandular swelling” on the left side of her neck. She complained that there had been variable swelling in the back and side of her neck over the last 2 years that was now worse. She was evaluated for this condition and serological tests for Epstein-Barr virus, bartonellosis, brucellosis, toxoplasmosis, and Lyme disease were negative. She was then advised and consented to lymph node biopsy. She was taken to the operating room elsewhere where she underwent local and standby anesthesia. The neck was prepped and local anesthetic was injected over the palpated mass. A 1.5 cm incision was made, carried through the skin to the subcutaneous tissue to what appeared to be a fibrotic area in the fascia along the lateral border of the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle. This area was dissected free and submitted to pathology. It was read as benign fibrous tissue on frozen section. The patient tolerated the procedure well and was taken to the recovery room in good condition. Initial diagnosis of the biopsied tissue disclosed fibrovascular fibromuscular tissue containing neural elements. Upon returning home the patient complained of persistent soreness in the neck and shoulder. Her mother noted that the pain was present immediately after the surgery and, though decreased with pain medication, was constant. She still had similar complaints at her 3-week checkup. Furthermore, her weakness became more aggravating and her arm tired. She worked part-time in a day care facility and found that lifting the toddlers became a difficult and pain-provoking activity. She started to notice tingling in the first three fingers of her left hand. She developed additional complaints of tonsillitis and sinusitis. Repeated serology was now positive for Epstein-Barr virus. At 6 weeks, still with persistent pain and weakness, she was referred to a neurologist who made the diagnosis of left spinal accessory nerve palsy. Inspection revealed along the posterior border of the SCM one third to two thirds junction a 1.5 cm transverse well-healed incision. The left shoulder was lower than the right (Fig. 15–1). The patient’s shoulder shrug strength was 4/5 on the left, 5/5 on the right. Abduction of the arm was possible to 90 degrees, but elevating beyond 90 degrees required moderate adduction of the arm medially. When she supinated the forearm this motion was facilitated. Forward extension of the flexed arm made the mild winging of the scapula more pronounced, whereas in a fully extended position the scapula did not wing (Fig. 15–1). SCM strength was normal bilaterally. Sensation was preserved. She was sent for electromyography and all three segments of the trapezius demonstrated positive sharp waves and fibrillation potentials, indicating complete denervation. No nascent motor unit potentials (MUPs) were seen, suggesting lack of reinnervation. This patient’s history suggested a spinal accessory nerve palsy by virtue of the onset of symptoms. The delay in symptomatology reflects the gradual atrophy of the trapezius and loss of muscular tone. Posterior triangle cervical lymph node biopsy may be associated with a 5 to 15% incidence of spinal accessory nerve palsy. The pathology report identified nerve fibers and strongly suggested nerve transection. The physical examination supports a complete palsy. The shoulder shrug or elevation is a combined function of the trapezius and levator scapulae and does not indicate a partial nerve injury. Electromyography (EMG) further supports a complete injury. The patient at 4 months would not show profuse degenerative findings for a neurapraxic injury, and if the injury was axonotmetic, nascent units should be seen in the most proximal segment of the trapezius. This not being the case, the patient was scheduled for surgery. Spinal accessory nerve palsy The spinal accessory nerve exits the jugular foramen at the base of the skull. It then courses under cover of the SCM, which it innervates, and emerges in close proximity to the great auricular and lesser occipital nerves. Finally, it passes down on the anterior surface of the trapezius muscle, innervating this muscle. As the spinal accessory nerve emerges from under the SCM, it assumes a relatively superficial course protected only by skin and subcutaneous fat. But it is not only this superficial location that puts the nerve at risk at this site but rather its close association with cervical lymph nodes. Although the nerve may be injured in trauma, gunshot wounds, or even robust lovemaking, by far the most common injury seen to this nerve is iatrogenic in nature—usually as a consequence of lymph node biopsy and occasionally associated with lipoma removal or radical neck dissection. The common clinical presentation of spinal accessory nerve palsy is after cervical lymph node biopsy or other operations in the posterior triangle of the neck. Often the patient notices the weakness immediately, but even with nerve transection some patients are not aware of symptoms for days or weeks after the operation. Invariably, with the passage of time all come to note the extreme difficulty in abducting the extremity of the affected side above the horizontal. They also note that the shoulder is slouched on the affected side and that the shoulder blade will “wing” posteriorly with abduction. Many patients notice severe pain in the shoulder immediately following the lymph node biopsy procedure. Although the spinal accessory nerve is generally considered a nearly pure motor nerve, it contains pain fibers that provoke a pain response with injury. A significant portion of the pain may also be due to mechanical dysfunction of the shoulder induced by the severe trapezius weakness.

Case Presentation

Case Presentation

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Anatomy

Anatomy

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree