Spinal Angiography: Technical Aspects

Key Point

The challenges of spinal angiography can be kept to a minimum by a methodical approach, careful expenditure of contrast, and a fastidious attention to details such as positioning and radiation use.

Indications

Spinal angiography can be intimidating to beginners. However, with practice and attention to expenditure of contrast in the early part of a procedure, it is a rare patient in whom a satisfactory examination cannot be obtained safely and completely at one session. Spinal angiography is used to evaluate certain vascular diseases, or to identify the origins of the spinal arteries prior to spinal surgery. Alternatively, the study may be necessary to evaluate lesions of the spine or vertebral column in the setting of a presurgical angiogram or embolization. When a complete spinal angiogram is required to search for a possible dural arteriovenous malformation or fistula, then the study must evaluate the entire dural vasculature from the skull base to the sacrum without omission (Table 3-1). Spinal dural arteriovenous malformations are notoriously elusive and difficult to see unless a technically adequate injection is made directly into the affected pedicle. Furthermore, dural arteriovenous malformations of the spine may present with conal symptoms or myelographic findings quite remote from the site of the fistula. Except for knowing that spinal dural arteriovenous malformations are more likely to be found in the thoracic and lumbar spine than in the cervical area, there is usually no a priori way of focusing a spinal angiogram for this disease unless one happens to have a hint of the origin from magnetic resonance arteriography or myelogram. A spinal angiogram in which “most” of the vessels were injected would be the equivalent of a cerebral angiogram for aneurysm detection in which “most” of the cerebral vessels were visualized, that is, not adequate in a certain number of patients.

Spinal tumors and intramedullary arteriovenous malformations, on the other hand, are often more defined with respect to suspected location. Even in a limited examination, it is, nevertheless, always worthwhile and usually essential to extend the study until the next neighboring uninvolved anterior spinal artery is visualized. The locations of the anterior and posterior spinal arteries are a particular concern in all situations where embolization of the paraspinal vessels is being considered.

Anesthesia During Spinal Arteriography

Since many of the critical vessels of interest during a spinal arteriogram are of such small size, the quality of images can be significantly degraded by a slight amount of motion or respiratory artifact. Most spinal angiograms are long procedures, and it is difficult for patients to remain absolutely still during that time. Depending on the indications for the study, a spinal angiogram can be focused on a known lesion or area, or may require a diagnostic evaluation of the entire spinal axis. In either event, the procedure is invariably tedious for the patient and is best done under general anesthesia, if possible. The main purpose of this is to avoid obtaining a technically inadequate study due to motion artifact. Furthermore, under general anesthesia, respirations can be suspended for the duration of each angiographic run, eliminating respiratory artifact. Occasionally, when embolization is considered for a known focal lesion in a particularly cooperative patient, the study can be performed with a lighter degree of anesthesia. Intravenous glucagon to suppress bowel motion during the lumbar phase of the study might be considered.

Technical Considerations in Spinal Arteriography

Spinal angiography, being something of a major undertaking for all involved, must be done with an eye to technical perfection (Figs. 3-1–3-3) in order to dispel subsequent considerations of whether the study might need to be repeated because of perceived errors or omissions (1,2,3,4,5).

Enumerating the vertebral bodies is the first task in a complete or focused spinal study, in order to avoid miscommunication about anatomic levels. The number of rib-bearing vertebrae must be counted under the fluoroscope and collated with the number of lumbar-type bodies. In situations of an indeterminate configuration, an arbitrary decision on a system of nomenclature

should be established and explicitly described in the report of the case, for example, “There are 11 rib-bearing vertebrae which for the purposes of this study will be numbered T1 to T11, and 5 nonrib-bearing vertebrae which will be numbered L1 to L5.” In addition, a plastic ruler included on the imaging field placed under the patient during the procedure can be helpful to avoid confusion about levels already studied and those yet needed.

should be established and explicitly described in the report of the case, for example, “There are 11 rib-bearing vertebrae which for the purposes of this study will be numbered T1 to T11, and 5 nonrib-bearing vertebrae which will be numbered L1 to L5.” In addition, a plastic ruler included on the imaging field placed under the patient during the procedure can be helpful to avoid confusion about levels already studied and those yet needed.

Table 3-1 Vessels Required for a Complete Spinal Arteriogram | |

|---|---|

|

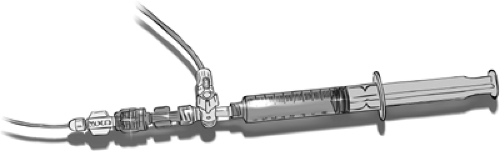

Figure 3-1. Setup for diagnostic spinal angiography. For diagnostic spinal angiography, a continuous flush system would generate too much dead space and, thus, excessive waste of contrast load with each injection. A three-way stopcock and a swivel adapter attached to the syringe and catheter provide an efficient means of rapidly searching for the next vessel and immediately toggling from syringe to injector tubing for the run. For coaxial spinal manipulations, a continuous flush system is used during interventional procedures.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|