Chapter 222 Spondylotic Myelopathy with Cervical Kyphotic Deformity

Ventral Approach

The development of cervical spine deformity may be secondary to advanced degenerative disease, trauma, neoplastic disease, or surgery.1 It may also occur in patients with systemic arthritides, such as ankylosing spondylitis and rheumatoid arthritis.

The most common cause of cervical kyphosis is iatrogenic (postsurgical).2 This most commonly occurs after laminectomy. The surgical procedure involves disruption of the dorsal tension-band. The incidence of clinically significant kyphosis in this situation may be as high as 21%.3 Kyphosis may also occur following ventral cervical surgery. This may be due to pseudarthrosis or failure to restore the anatomic cervical lordosis during surgery.4,5

Whatever the cause, the development of cervical deformity should be avoided and corrected when appropriate. Axial loading tends to further the kyphosis, thus creating a vicious cycle and progression of the deformity.6 The deformity tends to cause neck pain, which is mechanical in nature.7 The pain is due to a biomechanical disadvantage placed on the cervical musculature and degeneration of the adjacent cervical discs. In advanced cases, forward gaze, swallowing, and respiration may be adversely affected.

Ventral versus Dorsal Approach

Sagittal plane deformity in the cervical spine may be corrected ventrally,8–11 dorsally,12,13 or ventrally and dorsally (in combination).12,14–16 The ventral approach is one that is familiar to most spine surgeons and may be performed with minimal morbidity.

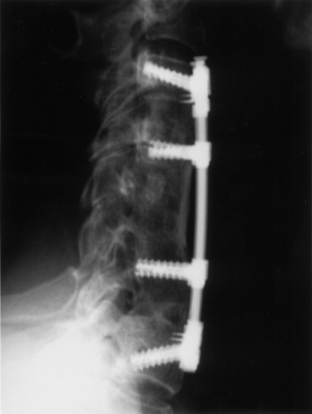

Many patients with cervical kyphosis have had a prior cervical operation, often a laminectomy (Fig. 222-1). A dorsal revision strategy is associated with increased morbidity with regard to wound complications, pain, and the risk of neurologic injury. A ventral approach is advantageous in that “virgin” surgical territory is entered. If a prior ventral approach had been performed, the same approach may be used without difficulty, or the opposite side of the neck may be entered for the revision. These factors decrease the morbidity associated with revision cervical surgery.

Using a dorsal-alone strategy, one is most often unable to correct cervical kyphosis significantly. Only if the deformity is “flexible” and is able to be corrected with cervical traction may a dorsal alone strategy be used. This finding is not at all common. More often, a ventral release procedure is required prior to the dorsal deformity correction procedure. A dorsal deformity correction procedure, with or without a ventral release, may not fully correct the deformity. Even with the use of cervical pedicle screws, Abumi et al. were able to correct cervical deformity only from 28.4 to 5.1 degrees of kyphosis, with all patients achieving a solid arthrodesis.12 A ventral strategy provides a better surgical leverage for deformity correction while providing very solid fixation points if intermediate points of fixation are used.6

As mentioned previously, using multiple points of intermediate fixation is optimal with ventral deformity correction strategies. This is accomplished by leaving intermediate vertebral bodies in place, instead of performing multiple adjacent corpectomies. These intermediate bodies provide solid fixation points for intermediate points of screw fixation. These intermediate points facilitate the “bringing of the spine” to a contoured implant to achieve further lordotic correction. They also provide three- or four-point bending forces to prevent deformity progression and construct failure.6 These intermediate fixation points may also be provided with dorsal lateral mass fixation, but entail the addition of a dorsal procedure, in addition to a ventral decompression procedure.

Axially dynamic cervical implants further add to the success of a ventral deformity correction procedure.17 These constructs are able to provide for the placement of multiple intermediate points of fixation. The dynamic aspect of the implant is able to off-load stresses at the screw/implant interface, which aids in the prevention of nonunion and construct failure, and also provides solid fixation for the prevention of cervical deformity progression.

Clinical Experience

We use a ventral-only approach for the correction of cervical kyphosis in specific clinical scenarios. This technique is optimally used when the kyphosis is fixed (i.e., rigid) and the facet joints are not ankylosed. If the facet joints or other dorsal elements are fused, a dorsal osteotomy is required. Ankylosis may easily be determined by fine-cut CT scanning. The clinical technique has been previously described,17,18 and surgical steps will be briefly outlined here.

We have reported our experience with this technique with 12 patients. A dynamic implant was us in most patients.17 The majority of patients presented with mechanical neck pain as part of their symptom complex. The average magnitude of deformity correction (preoperative to postoperative) was 20 degrees of lordosis. The average postoperative sagittal angle was 6 degrees of lordosis. The average change in the sagittal angle during the follow-up period was 2.2 degrees of lordosis.

Using this ventral technique, lordosis was attained in all but one patient (Fig. 222-2). This posture was effectively maintained during the follow-up period. All patients demonstrated improvement postoperatively, and three had complete resolution of their preoperative symptoms.

Albert T.J., Vacarro A. Postlaminectomy kyphosis. Spine. 1998;23:2738-2745.

Buttler J.C., Whitecloud T.S.III. Postlaminectomy kyphosis: causes and surgical management. Clin Orthop North Am. 1992;23:505-511.

Herman J.M., Sonntag V.K. Cervical corpectomy and plate fixation for post-laminectomy kyphosis. J Neurosurg. 1994;80:963-970.

Kaptain G.J., Simmons N., Replogle R.E., Pobereskin L. Incidence and outcome of kyphotic deformity following laminectomy for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. J Neurosurg. 2000;93(Suppl 2):199-204.

Steinmetz M.P., Kager C., Benzel E.C. Anterior correction of postsurgical cervical kyphosis. J Neurosurg. 2003;98(Suppl 2):1-7.

Zdeblick T.A., Bohlman H.H. Cervical kyphosis and myelopathy: treatment by anterior corpectomy and strut-grafting. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1989;71:170-182.

1. Johnston F.G., Crockard H.A. One stage internal fixation an anterior fusion in complex cervical spinal disorders. J Neurosurg. 1995;82:234-238.

2. Albert T.J., Vacarro A. Postlaminectomy kyphosis. Spine. 1998;23:2738-2745.

3. Kaptain G.J., Simmons N., Replogle R.E., Pobereskin L. Incidence and outcome of kyphotic deformity following laminectomy for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. J Neurosurg. 2000;93(Suppl 2):199-204.

4. Caspar W., Pitzen T. Anterior cervical fusion and trapezoidal plate stabilization for re-do surgery. Surg Neurol. 1999;52:345-352.

5. Geisler F.H., Caspar W., Pitzen T., et al. Reoperation in patients after anterior cervical plate stabilization in degenerative disease. Spine. 1998;23:911-920.

6. Benzel E.C. Biomechanics of spine stabilization. Rolling Meadows, IL: American Association of Neurological Surgeons; 2001.

7. Katsuura A., Hukuda S., Imanaka T., et al. Anterior cervical plate used in degenerative disease can maintain cervical lordosis. J Spine Disord. 1996;9:470-476.

8. Buttler J.C., Whitecloud T.S.III. Postlaminectomy kyphosis: causes and surgical management. Clin Orthop North Am. 1992;23:505-511.

9. Cattrell H.S., Clark G.J.Jr. Cervical kyphosis and instability following multiple laminectomies in children. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1967;49:713-720.

10. Herman J.M., Sonntag V.K. Cervical corpectomy and plate fixation for post-laminectomy kyphosis. J Neurosurg. 1994;80:963-970.

11. Zdeblick T.A., Bohlman H.H. Cervical kyphosis and myelopathy: treatment by anterior corpectomy and strut-grafting. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1989;71:170-182.

12. Abumi K., Shono Y., Taneichi H. Correction of cervical kyphosis using pedicle screw fixation systems. Spine. 1999;24:2389-2396.

13. Callahan R.A., Johnson R.M., Margolis R.N. Cervical facet fusion for control of instability following laminectomy. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1977;59:991-1002.

14. Heller J.G., Silcox D.H.III, Sutterlin C.E.III. Complications of posterior cervical plating. Spine. 1995;20:2442-2448.

15. McAfee P.C., Bohlman H.H., Ducker T.B. One stage anterior cervical decompression and posterior stabilization. A study of one hundred patients with a minimum of two years of follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1995;77:1791-1800.

16. Savini R., Parisini P., Cervellati S. The surgical treatment of late instability of flexion-rotation injuries in the lower cervical spine. Spine. 1987;12:178-182.

17. Steinmetz M.P., Kager C., Benzel E.C. Anterior correction of postsurgical cervical kyphosis. J Neurosurg. 2003;98(Suppl 2):1-7.

18. Steinmetz M.P., Stewart T.J., Kager C., et al. Cervical deformity correction. Neurosurgery. 2007;60(Suppl 1):S90-S97.

Dorsal Approach

Cervical spondylotic myelopathy (CSM) is a chronic spinal degenerative condition characterized by progressive symptoms of neck pain, upper extremity numbness and motor weakness, spastic gait disturbance, urinary dysfunction, hyperreflexia, and impotence. The primary pathophysiologic mechanism is a progressive narrowing of the sagittal diameter of the spinal canal due to a host of mechanical factors.1 White and Panjabi have subdivided the mechanical factors into two groups: static factors (congenital spinal canal stenosis, disc herniation, osteophytosis, and ligament hypertrophy) and dynamic factors (abnormal forces placed on the spinal cord during normal range of motion of the cervical spine).2 As the degenerative spinal elements compress the spinal cord, blood vessels can simultaneously be compressed, causing chronic cord ischemia and myelomalacia.3 Several studies have demonstrated that early surgical intervention can improve prognosis and prevent continued neurologic decline, as well as decrease the risk of sudden spinal cord injury from minor events.4–7

There has been much debate as to the most optimal surgical approach for a patient with CSM, and once the recommendation has been made for surgery, often the approach is tailored to the individual patient. Assessment of the sagittal alignment of the patient’s cervical spine is of utmost importance when considering the best surgical approach, because CSM is often associated with loss of cervical lordosis (so-called “spine straightening”) or cervical kyphotic deformity. In the case of cervical kyphotic deformity, the spinal cord shifts ventrally in the canal and abuts the ventral spinal elements at the apex of the deformity. As the deformity progresses, the static and dynamic mechanical stresses applied to the spinal cord increase, leading to worsening neurologic function.8 To most effectively manage patients with this pathologic variation, surgical intervention must be targeted at adequate decompression of the neural elements and prevention of progression, if not outright correction, of the cervical kyphosis.

There are three major options for surgical management of CSM: the ventral approach, dorsal approach, or a combination of the two. Several studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of the ventral approach in treating CSM.9,10 The ventral approach is heavily favored by many surgeons who treat CSM, especially in the presence of a cervical kyphotic deformity.11 The ventral approach can be used to treat pathology limited to one or two levels (via ventral cervical discectomy and fusion) and over three or more levels (via subtotal cervical corpectomy and strut graft, usually in conjunction with dorsal instrumentation). Unfortunately, long-segment ventral procedures have been associated with a high rate of pseudarthrosis, graft dislodgement and subsidence, or construct failure.9,12 Several options are available if the surgeon chooses to use solely a dorsal approach. However, because the source of the pathology in CSM with kyphotic deformity is ventral to the spinal cord, the chosen dorsal approach must not only effectively decompress the neural elements, but also correct the kyphotic deformity to allow the spinal cord to migrate dorsally away from the ventral compressive elements. In this chapter, the focus is placed on the major dorsal approaches available to treat CSM and the pros and cons of each.

Cervical Laminectomy and Lateral Mass Fusion

Cervical laminectomy for the treatment of CSM has been shown to be safe and effective. As a stand-alone treatment for CSM, cervical laminectomy has recently fallen out of favor with many surgeons because of the risk of development of postlaminecomy kyphosis. Ryken et al.13 performed a systematic review of the National Library of Medicine and the Cochrane database to examine the efficacy of cervical laminectomy for the treatment of CSM and concluded that it remains a viable consideration for treatment of CSM. They found that the risk of developing postlaminectomy kyphosis in patients undergoing laminectomy for CSM ranges from 14% to 47%. It is unclear how this risk relates to clinical outcome; however, a straight or kyphotic cervical spine alignment is associated with an augmented risk of developing a postlaminectomy kyphosis.

In an attempt to avoid the development of late kyphosis after laminectomy, many surgeons opt to perform a lateral mass fusion at the time of laminectomy. Gok et al.14 retrospectively reviewed 54 patients who underwent cervical laminectomy and fusion for CSM. Patients were selected if they had clinical signs of myelopathy and cervical lordosis or straight spine with advanced age (>65 years) and significant medical comorbidities. In this study, 81% of patients improved in Nurick grade, and the remaining 19% remained the same. Ten percent required revision surgery, and only 4% (2 patients) had lateral mass screw pull-out. Anderson et al.15 performed a systematic review of the Cochrane database and the National Libary of Medicine to examine the efficacy of cervical laminectomy and fusion for CSM. Although the evidence is largely class III, the investigators concluded that 70% to 95% of patients show neurologic improvement with this procedure, and overall recovery is approximately 50% of the initial Japanese Orthopaedic Association (JOA) score deficit. Several other studies16–18 reported good success with cervical laminectomy and fusion. However, patients with preexisting cervical kyphosis were universally excluded from all of these studies.

Although cervical laminectomy with or without lateral mass fusion may be successful in the treatment of CSM in patients with lordotic or slightly straight cervical alignment, these procedures are contraindicated in patients with a kyphotic spine. Because the spinal cord is draped over a kyphotic deformity, it does not shift dorsally after laminectomy. This often results in suboptimal surgical results and progression of neurologic decline. Furthermore, a laminectomy in the presence of kyphosis may worsen the deformity.13,14,17 Therefore, kyphosis in the setting of CSM is considered to be a contraindication to laminectomy with or without lateral mass fusion.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree