INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW OF DEMENTIA STAGING

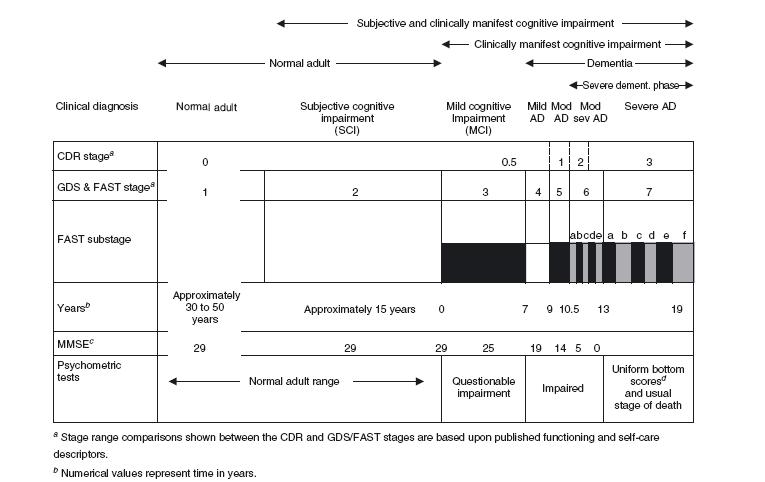

Dementia is a progressive pathological process extending over a period of many years. Clinicians and scientists have long endeavoured to describe the nature of dementia progression. Such descriptions have generally been encompassed within two broad categories: global staging and more specific staging, sometimes referred to as axial or multi-axial staging. A comparison of the major current dementia staging systems with the most widely used mental status assessment in Alzheimer’s disease, the major cause of dementia, is shown in Figure 31.1.

This Figure illustrates some of the major potential advantages of staging. These advantages include: (i) staging can identify premorbid, but potentially manifest conditions which may be associated with the evolution of subsequent dementia, such as subjective cognitive impairment, a condition which is not differentiated with mental status or psychometric tests; (ii) staging can be very useful in identifying subtle predementia states, such as mild cognitive impairment (MCI), wherein mental status assessments and psychometric tests, while frequently altered, are generally within the normal range and, consequently, are not reliable markers17-19 ; and (iii) staging can track the latter 50% of the potential time course of dementias such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), when mental status assessments are virtually invariably at bottom (zero) scores20. Furthermore, apart from their utility in portions of dementia where mental status and psychometric assessments are out of range, or insensitive, there are clear data indicating that staging procedures can more accurately and sensitively identify the course of dementia in the portion of the condition which is conventionally charted with mental status assessments. This latter evidence comes from longitudinal investigation of the course of AD9, pharmacological treatment investigation of AD21-23, and study of independent psychometric assessments of AD24. For example, longitudinal study has demonstrated that the Functional Assessment Staging procedure (FAST)5 and the Global Deterioration Scale (GDS)3 accounted for more than twice the variance in the course of AD over a five-year mean interval, compared to the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)7,9. When employed together, the GDS and the FAST staging procedures explained nearly three times the variance in the temporal course of AD compared to the MMSE (i.e. change in measure versus change in time), with the MMSE encompassing only 10% of temporal change variance and the GDS and FAST together encompassing 28% of the temporal change variance9. In pharmacological studies, staging procedures have frequently demonstrated sensitivity to effects of the interventions in pivotal studies where mental status assessment has not shown a significant effect. This superiority in the demonstration of pharmacological treatment efficacy for staging procedures over mental status assessment has been seen for both classes of currently approved pharmacotherapeutic agents; that is, for N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist treatment decreasing glutamate-induced excitotoxicity, and for cholinesterase inhibitor treatment enhancing cholinergic brain functioning. For example, a pivotal, multicentre trial associated with worldwide approvals of memantine treatment for AD found a robust statistically significant effect of the memantine, NMDA receptor antagonist treatment with the FAST staging procedure, but no significant effect was observed with the MMSE evaluation21. Similarly, in a pivotal study associated with worldwide approval of the cholinesterase inhibitor, rivastigmine, it was found that low dose treatment (1-4mg/day) was associated with significant improvement on the GDS staging procedure, but not on the MMSE assessment22. Additionally, study of predominantly institutionalized persons with more advanced AD in the latter portion of the MMSE range (i.e. with MMSE scores of 10 or below), with specially designed psychometric procedures for advanced AD patients, have clearly shown that the FAST staging procedures can robustly track progressive change in these more advanced AD patients, in conjunction with special psychometric procedures, whereas the MMSE does not sensitively change in this more severe range24. Another potential advantage of staging procedures in comparison with mental status

Figure 31.1 Typical time course of normal brain ageing; mild cognitive impairment associated with Alzheimer’s disease and the dementia of Alzheimer’s disease. AD, Alzheimer’s disease; CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating1,2; GDS, Global Deterioration Scale3,4; FAST, Functional Assessment Staging5,6; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination7; Mod AD, moderate Alzheimer’s disease; Mod sev AD, moderately severe Alzheimer’s disease. Copyright © 2007, 2009 Barry Reisberg, MD. All rights reserved

a Stage range comparisons shown between the CDR and GDS/FAST stages are based upon published functioning and self-care descriptors.

b Numerical values represent time in years.

For GDS and FAST stage 1, the temporal values are subsequent to the onset of adult life.

For GDS and FAST stage 2, the temporal value is prior to onset of mild cognitive impairment symptoms.

For GDS and FAST stage 3 and above, the values are subsequent to the onset of mild cognitive impairment symptoms.

In all cases, the temporal values refer to the evolution of Alzheimer’s disease pathology.

All temporal estimates are based upon the GDS and FAST scales and were initially published based upon clinical observations in Reisberg, Geriatrics 1986; 41(4): 30-468. These estimates have been supported by subsequent clinical and pathological cross-sectional and longitudinal investigations (e.g. Reisberg et al., Int Psychogeriatr 1996; 8: 291-3119; Bobinski et al., Dementia 1995; 6: 205-1010; Bobinski et al., J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1997; 56: 414-2011;

Kluger et al., J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1999; 12: 168-7912; Prichep et al., Neurobiol Aging, 2006; 27: 471-8113 ; Reisberg and Gauthier, Int Psychogeriatr2008; 20: 1-1614; Wegiel et al., Acta Neuropathol 2008; 116: 391-40715; Reisberg et al., Alzheimers Dement 2010; 6(1): 11-2416).

The spacing in the figure is approximately proportional to the temporal duration of the respective stages and substages, with the exception of GDS and FAST stage 1, for which the broken lines signify an abbreviated temporal duration spacing for this normal adult condition which lasts approximately 30 to 50 years.

c MMSE scores are approximate mean values from prior published studies.

d For typical adult psychometric tests.

or psychometric assessment of AD and other dementias, is in identifying the management concomitants of severity assessments25,26. Staging procedures have also been successfully applied postmortem to retrospectively assess the diagnoses (i.e. AD or other non-AD dementia) of a diverse assortment of dementia-related cases available for ‘brain banking’, but on which no antemortem clinical data were available27. Similarly, postmortem retrospective staging procedures have been successful in establishing remarkably robust clinicopathological correlations in longitudinally studied AD cohorts10,11,15,20.

Efforts to globally stage progressive dementia can be traced back at least to the early nineteenth century when the English psychiatrist, James Prichard, described four stages in the progression of dementia: ‘(1) impairment of recent memory, (2) loss of reason, (3) incomprehension, (4) loss of instinctive action’28,29. More recently, the American Psychiatric Association’s30 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd edition (DSM-III) recognized three broad stages in its definition of primary degenerative dementia30. Subsequently, in 1982, two more detailed global descriptions of the progression of dementia were published. One of these, the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale1, describes five broad stages from normality to severe dementia. The other, the Global Deterioration Scale (GDS)3, identifies seven clinically recognizable stages from normality to most severe dementia of the Alzheimer type. A recently published abridged version of the GDS is shown in Table 31.131.

Complete versions of the CDR and the GDS scales can be found in the literature (e.g. for the original CDR, references1,32 and for the CDR ‘current version’, reference2; for the GDS, reference3, and for the tabular format of the GDS, reference4). These two global staging instruments, the GDS and the CDR, are generally compatible except that the GDS is more detailed and specific and identifies two stages which the CDR staging does not.

One of these stages identified by the GDS staging procedure but not by the CDR is a stage in which subjective complaints of cognitive deficit occur in the absence of clinically identifiable symptoms (GDS stage 2). These subjective complaints are now recognized as occurring very commonly in older persons (e.g.33-35). Although this stage of subjective complaints continues to be identified only by the GDS staging system, studies have indicated that persons with these complaints are at increased risk for subsequent overt dementia (e.g.12,16,36-38). A distinct diagnostic terminology, namely, ‘subjective cognitive impairment’ (SCI), has recently been suggested for otherwise healthy older persons with these symptoms who are free of overtly manifest symptoms of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia14,39. A recent study, which is apparently the first to systematically examine the prognosis of GDS stage 2, SCI persons, in comparison with persons with no cognitive impairment (NCI, GDS stage 1), from the perspective of the subsequent development of MCI or dementia, has indicated the true morbidity associated with this SCI condition. Over a mean seven-year follow-up, the risk of subsequent decline to MCI or dementia was 4.5-times greater in persons with SCI (GDS stage 2) than in persons who are free of these subjective complaints, after controlling for differences in age and other demographic variables, as well as follow-up time16. Physiological differences between otherwise healthy older persons with these subjective complaints of cognitive impairment and similarly aged persons without these symptoms (i.e. between GDS stage 2 and GDS stage 1 subjects) have now been reported for brain metabolism and cortisol levels40,41. Longitudinal studies are also presently confirming13,14 a previously estimated 15-year duration8 for this GDS stage 2 condition, identifying subjective impairment only, in the evolution of brain ageing and AD pathology.

The GDS staging measure and associated assessments from the GDS staging system also identify a stage, GDS stage 3, for which the terminology mild cognitive impairment (MCI) was originally coined in 198842. ThisGDS stage 3 is described, in part, as a stage in which: (i) the ‘earliest clear-cut deficits’ become manifest; (ii) ‘objective evidence of memory deficit is obtained only with an intensive interview’, and (iii) there is ‘decreased performance in demanding employment and social settings’. Many of the early observations with respect to the nature of MCI were made using this GDS stage 3 definition (see17 for a review), and the GDS 3 definition of MCI remains compatible

Table 31.1 Abridged global deterioration scale

Stage 1: NCI. No subjective memory deficit (no cognitive impairment); no problems with activities of daily living. Stage 2: SCI. Subjective cognitive impairment (subjective memory and/or other cognitive complaints): observations, sometimes accompanied by complaints, of being forgetful, such as of difficulties with recall of names, and/or of misplacing objects. Stage 3: MCI. Earliest subtle deficits (mild cognitive impairment): difficulties often noted at work; may have become lost; may have misplaced a valuable object. Stage 4: Mild dementia. Clear deficits on clinical examination (moderate cognitive impairment): decreased knowledge of personal and/or current events; often difficulties with finances or shopping or meal preparation or travel. Stage 5: Moderate dementia. Can no longer survive independently in the community without some assistance (moderately severe cognitive impairment): difficulty with recall of some important personal details (e.g. address, names of one or more important schools attended); may require cueing for activities for daily living. Stage 6: Moderately severe dementia. Largely unable to verbalize recent events in their life (severe cognitive impairment): may forget name of spouse; incontinence develops as this stage progresses; requires increasing assistance with activities for daily living such as dressing and showering. Increased behavioural problems (e.g. agitation) or other personality problems are common. Stage 7: Severe dementia. Few intelligible words or no verbal abilities (very severe cognitive impairment): the ability to walk is lost as this stage evolves. Later, basic capacities such as the ability to sit up independently, to smile, and to move and/or to hold up the head independently are progressively lost. |

Copyright © 1983, 2008, 2009 Barry Reisberg, MD. All rights reserved.

2009 abridged version. Original abridged version published in Canadian Medical Association Journal 2008; 179(12): 1281. Modified from Reisberg B, Ferris SH, de Leon MJ et al. The global deterioration scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. Am J Psychiatry 1982; 139: 1136-9.

with the current international consensus definition of MCI, published by Winblad et al. in 200419. The CDR staging methodology identifies a CDR 0.5 stage originally termed ‘questionable dementia’, which is somewhat broader in scope than the MCI entity, and which encompasses some of early (mild) dementia, as well as the MCI clinical timeframe.

At the other end of the pathological spectrum, the CDR does not identify any stage beyond that in which dementia patients ‘require much help with personal care’ and are ‘often incontinent’. In contrast, the GDS identifies a final seventh GDS stage in which patients are already incontinent and over the course of which language and motor capacities are progressively lost. Importantly, the CDR does not stage or substage the latter portion of the dementia of AD, representing nine or more years of potential life and continuing decline for these patients (see Figure 31.1

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree