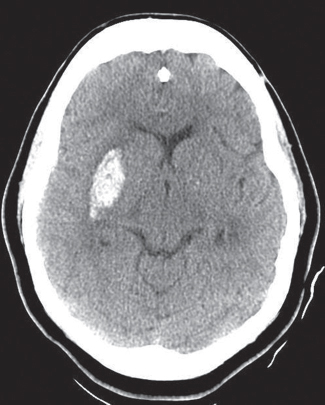

53 What is a stroke? A neurological deficit resulting from poor perfusion of a portion of the brain or brainstem What is the mechanism by which poor perfusion leads to neuronal injury and death? An inability to undergo aerobic glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation leads to: • Deficiency of ATP and failure of the Na+/K+ ATPase (resulting in cell swelling) • Failure of the Ca2+,Mg2+ ATPase (leading to an influx of Ca2+) • Reduced protein synthesis (which requires ATP) • Activation of phospholipases, proteases, and endonucleases (by the increased intracellular Ca2+) • Accumulation of free radicals (leading to membrane lipid peroxidation, DNA fragmentation, and protein cross-linking and fragmentation) • Accumulation of glutamate and other excitatory neurotransmitters (leading to excitotoxic damage) What are the three types of stroke? • Ischemic infarct: most common (87% of strokes)1 • Hemorrhagic stroke (10% of strokes)1 • Venous infarct What are some modifiable risk factors for stroke? Hypertension, tobacco smoking (doubles the risk of ischemic stroke2), heavy alcohol consumption, diabetes, dysrhythmia, pregnancy, physical inactivity, low HDL cholesterol What EEG changes are typically seen in the penumbra region? Isoelectric silence Which brain regions are most susceptible to global cerebral ischemia (“watershed zones”)? Those regions at the most distal fields of arterial irrigation. The border zone between ACA and MCA distributions is at greatest risk. A stroke in this watershed region may be seen as a “sickle-shaped” necrotic band a few centimeters lateral to the interhemispheric fissure in the setting of hypotensive episodes. What inflammatory conditions can lead to vessel occlusion and cerebral infarcts? Arteritis • Infectious • Polyarteritis nodosa • Primary (granulomatous) angiitis of the CNS What is cerebral autosomal-dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL)? A hereditary condition leading to stroke. Caused by mutations in the Notch3 gene. Characterized by recurrent strokes and dementia. Diagnosis is by demonstration of basophilic, PAS-positive granules in walls of affected vessels as well as in skin and muscle.3 What is cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA)? A condition (may be sporadic or familial) in which an amyloidogenic peptide (Aβ40) is deposited in the walls of meningeal and cortical vessels, weakening vessel walls and resulting in an increased risk of hemorrhage4 Where do emboli causing embolic strokes typically originate? • Cardiac mural thrombi (e.g., in atrial fibrillation, MI, valvular disease) • Paradoxical thrombi in patients with cardiac anomalies or patent foramen ovale • Emboli from carotid artery atheromatous plaques Which artery is most frequently occluded by embolic strokes? What is the most common underlying cause of spontaneous (nontraumatic) intra cerebral (intraparenchymal) hemorrhage (ICH)? Hypertension (>50% of ICHs). Other causes include systemic coagulopathy, neoplasms, amyloid angiopathy, vasculitis, aneurysms, vascular malformations, drugs (e.g., cocaine) Where are the most common sites for hypertensive intra-cerebral hemorrhage? Putamen (50–60%), thalamus, pons, cerebellum (especially dentate nuclei) Fig. 53.1 Axial CT scan revealing right putaminal hemorrhage in a hypertensive patient. What are lacunar infarcts? Small, cavitary (lacunar = “lake-like”) areas of tissue loss (<15 mm wide) occurring in the lenticular nucleus (most common), caudate, thalamus, pons, internal capsule, and deep white matter (least common) due to hypertensive changes and resultant infarction of the deep penetrating arteries and arterioles that supply these structures. What is a transient ischemic attack (TIA)? Transient (<24 hours) neurological deficit resulting from poor perfusion of a region of the brain or brainstem What is the risk of stroke after TIA? 5% of TIA patients will have a stroke within 48 hours,7 and 10% will have a stroke within 90 days1,7 How long after initial stroke symptoms can an ischemic stroke typically be visualized on CT? Most strokes can be seen as a low density by 24 hours. Some ischemic strokes may reveal early (hyperacute, <6 hours) signs that may confer a worse prognosis (particularly in MCA strokes).8 What are some early (<6 hours) signs of ischemic stroke that may be seen on CT or MRI? • CT often normal9 • Loss of gray-white interface • Mass effect (effacement of sulci, midline shift)10,11 • Enhancement9 • Hyperdense artery sign (intraarterial clot leads to increased arterial density on noncontrast CT) • Insular ribbon sign: loss of the normally striated appearance of the insular cortex due to edema in the distribution of the lenticulostriate arteries10 What is the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS)? A scale (based on the Cincinnati stroke scale) designed to assess stroke severity in suspected stroke patients. Higher scores indicate more widespread deficits (likely due to occlusion or larger and/or more proximal vessels).12,13 How are ischemic strokes treated? • Airway, ventilator support, and supplemental oxygen • Maintenance of normothermia, normotension, and normoglycemia • Close monitoring of vitals (cardiac monitoring), neuro status, and laboratories (e.g., CBC, electrolytes)14 • Aspirin, anticoagulation • Steroids (for steroid-responsive vasculitis) • Mannitol (for mass effect) • Keep patient supine with modest head elevation (to maximize CBF) • Correction of anemia In cases where the patient presents within a 4.5-hour window thrombolytic therapy (IV or IA tPA) may be indicated. Other procedures potentially indicated in early stages include mechanical embolectomy and reduction of mass effect (e.g., in the presence of brainstem compression as in cerebellar stroke) What is the time window during which IV tPA may be indicated for treatment of ischemic stroke? Up to 4.5 hours following onset of symptoms (4.5 hours from the time the patient was last seen without symptoms). This window was formerly set at 3 hours, but was increased to 4.5 hours in select patients (age <80, baseline NIHSS score <25, no prior stroke history if diabetic) due to the results of the 2009 European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study (ECASS) III.15,16 What are some of the absolute contraindications to IV tPA? • ICH on admission CT or history of ICH • Clinical signs of SAH • Known intracranial aneurysm, neoplasm, or AVM • Hypodensity of more than one third of the cerebral hemisphere on CT (multilobar infarction) • Active internal bleeding or acute trauma • Coagulopathy (INR >1.7 or PT >15 seconds, platelet count <100,000, heparin in last 48 hours) • Hypertension (SBP >185 mm Hg or DBP >110 mm Hg) not controlled with nicardipine or IV labetalol • Intracranial or intraspinal surgery, serious head trauma, or previous stroke within last 3 months17,18 How long should anticoagulation and antiplatelet drugs be held following IV tPA treatment? What is the primary risk associated with the use of IV tPA? Intracranial hemorrhage (seen in 6.4 to 8.8% of patients receiving IV tPA compared with 0.6 to 3.4% receiving placebo)19,20 What are the indications for endovascular treatment of ischemic stroke (intraarterial tPA or mechanical embolectomy)? Failure of IV tPA, time window 4.5 to 6 hours (ineligibility for IV tPA due to time criteria) True or false: Hypertension should be treated aggressively in stroke patients. False. Hypertension may be needed in stroke patients to maintain cerebral blood flow and should be treated cautiously. Blood pressure should be monitored every 15 minutes in post IV-tPA patients, and SBP >180 or DBP >105 should be treated with IV labetalol, nicardipine infusion, or sodium nitroprusside as per American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines.21 When is anticoagulation indicated in stroke patients? Heparin therapy is rarely indicated in acute ischemic stroke.22 High-intensity warfarin therapy has been proven beneficial in acute ischemic stroke in the setting of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome.23 When is decompressive craniectomy indicated in stroke patients? Suboccipital craniectomy may reduce mortality in patients with cerebellar stroke and progressive neurological deterioration/deficit due to brainstem compression.24–26 Early (<24 hours) decompressive hemicraniectomy has been shown to reduce mortality and improve functional outcome in select patients with large hemispheric infarctions (e.g., malignant MCA territory infarction).27–29 When is carotid endarterectomy indicated in stroke patients? When high-grade carotid stenosis (50–99%) is demonstrated ipsilateral to a neurological deficit30 What neurological deficits are associated with occlusion of the MCA? • Contralateral (CL) bodily weakness (UE > LE) • CL weakness of lower face • CL sensory loss (UE, LE, and face) • CL neglect • Ipsilateral (IL) gaze preference • CL homonymous hemianopsia In cases where dominant hemisphere is involved: • Aphasia (receptive and/or expressive) • Gerstmann syndrome What is Gerstmann syndrome? Neurological deficits resulting from damage (e.g., due to infarct, mass) of dominant parietal lobe, including: • Agraphia (inability to write) • Left-right confusion • Digit agnosia (inability to identify finger by name) • Acalculia (inability to perform rudimentary mathematics) What neurological deficits are associated with occlusion of the ACA? CL weakness (LE > UE), abulia, aphasia What neurological deficits are associated with occlusion of the PCA? • CL homonymous hemianopsia (macular sparing present due to redundant supply from MCA) • Balint syndrome: poor hand-eye coordination, oculomotor apraxia (poor voluntary guidance of eye movements), simultanagnosia (inability to simultaneously perceive two objects) • Anton-Babinski syndrome: “cortical blindness,” the patient is blind but does not admit to blindness and may confabulate or appear unaware of the deficit • Alexia (inability to read) • Dejerine-Roussy syndrome (thalamic pain syndrome) What neurological deficits are associated with occlusion of the vertebral artery? Lateral (Wallenberg) or medial (Dejerine) medullary syndrome What is Wallenberg syndrome? Also known as lateral medullary syndrome. A syndrome classically attributed to occlusion of PICA, although occlusion of the vertebral artery is more commonly (80–85%) the cause.31,32 Symptoms include: • IL facial pain and sensory loss (due to damage to the descending tract and nucleus of V) • IL Horner’s syndrome (due to damage to the descending sympathetic tract) • Hoarseness and dysphagia (due to damage to the nucleus ambiguous) • Possible vertigo, nystagmus, diplopia, and IL cerebellar deficits, e.g., ataxia (due to damage to the inferior cerebellar peduncle and vestibular nuclei) • CL loss of bodily pain and temperature sensation (due to damage to the spinothalamic tract) • Palatal myoclonus may be seen due to disruption of the central tegmental tract. What symptoms are expected with medial medullary syndrome (Dejerine syndrome)? • Contralateral hemiparesis (due to damage to the ipsilateral pyramid) • Contralateral sensory deficits (due to damage to the medial lemniscus) • Ipsilateral paralysis and atrophy of tongue muscles (due to damage to the hypoglossal nucleus and/or nerve) What neurological deficits are associated with occlusion of AICA? Lateral pontine syndrome, also known as Marie-Foix syndrome. Symptoms include: • CL loss of pain and temperature (due to damage to the spinothalamic tract) • IL weakness of lower face, with or without decreased salivation and lacrimation, with or without loss of taste to anterior two thirds of tongue (due to damage to the facial nerve and nucleus) • Nystagmus, vertigo (due to damage to the spinal trigeminal nucleus and tract) • IL hearing loss (due to damage to the cochlear nuclei) • IL cerebellar signs (due to damage to the middle and inferior cerebellar peduncles) • IL Horner’s syndrome (due to damage to the descending sympathetic fibers) What neurological deficits are associated with occlusion of the anterior choroidal artery? Damage to posterior limb of IL internal capsule. Symptoms include: • CL weakness (corticospinal pathway) • CL sensory loss (dorsal columnar pathway) • CL homonymous hemianopsia (visual pathway) 1. Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2009 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation 2009;119:480–486 PubMed 2. Wang TJ, Massaro JM, Levy D, et al. A risk score for predicting stroke or death in individuals with new-onset atrial fibrillation in the community: the Framingham Heart Study. JAMA 2003;290:1049–1056 PubMed 3. Dichgans M. CADASIL: a monogenic condition causing stroke and subcortical vascular dementia. Cerebrovasc Dis 2002;13(Suppl 2):37–41 PubMed 4. Greenberg SM. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy: prospects for clinical diagnosis and treatment. Neurology 1998;51:690–694 PubMed 5. Rordorf G, Koroshetz WJ, Copen WA, et al. Regional ischemia and ischemic injury in patients with acute middle cerebral artery stroke as defined by early diffusion-weighted and perfusion-weighted MRI. Stroke 1998;29:939–943 PubMed 6. Satoh S, Shirane R, Yoshimoto T. Clinical survey of ischemic cerebrovascular disease in children in a district of Japan. Stroke 1991;22:586–589 PubMed 7. Johnston SC, Gress DR, Browner WS, Sidney S. Short-term prognosis after emergency department diagnosis of TIA. JAMA 2000;284:2901–2906 PubMed 8. Marks MP, Holmgren EB, Fox AJ, Patel S, von Kummer R, Froehlich J. Evaluation of early computed tomographic findings in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 1999;30:389–392 PubMed 9. Wall SD, Brant-Zawadzki M, Jeffrey RB, Barnes B. High frequency CT findings within 24 hours after cerebral infarction. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1982;138:307–311 PubMed 10. Kunst MM, Schaefer PW. Ischemic stroke. Radiol Clin North Am 2011;49:1–26 PubMed 11. Yuh WT, Crain MR, Loes DJ, Greene GM, Ryals TJ, Sato Y. MR imaging of cerebral ischemia: findings in the first 24 hours. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1991;12:621–629 PubMed 12. Brott T, Adams HP Jr, Olinger CP, et al. Measurements of acute cerebral infarction: a clinical examination scale. Stroke 1989;20:864–870 PubMed 13. Fischer U, Arnold M, Nedeltchev K, et al. NIHSS score and arteriographic findings in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 2005;36:2121–2125 PubMed 14. Adams HP Jr, Adams RJ, Brott T, et al; Stroke Council of the American Stroke Association. Guidelines for the early management of patients with ischemic stroke: A scientific statement from the Stroke Council of the American Stroke Association. Stroke 2003;34:1056–1083 PubMed 15. Del Zoppo GJ, Saver JL, Jauch EC, Adams HP Jr; American Heart Association Stroke Council. Expansion of the time window for treatment of acute ischemic stroke with intravenous tissue plasminogen activator: a science advisory from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2009;40:2945–2948 PubMed 16. Lansberg MG, Bluhmki E, Thijs VN. Efficacy and safety of tissue plasminogen activator 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke: a metaanalysis. Stroke 2009;40:2438–2441 PubMed 17. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. N Engl J Med 1995;333:1581–1587 PubMed 18. Adams HP Jr, Brott TG, Furlan AJ, et al. Guidelines for thrombolytic therapy for acute stroke: a supplement to the guidelines for the management of patients with acute ischemic stroke. A statement for healthcare professionals from a Special Writing Group of the Stroke Council, American Heart Association. Circulation 1996;94:1167–1174 PubMed 19. Barer D. ECASS II: intravenous alteplase in acute ischaemic stroke. European Co-operative Acute Stroke Study-II. Lancet 1999;353:66–67, author reply 67–68 PubMed 20. Tilley BC, Lyden PD, Brott TG, Lu M, Levine SR, Welch KM. Total quality improvement method for reduction of delays between emergency department admission and treatment of acute ischemic stroke. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. Arch Neurol 1997;54:1466–1474 PubMed 21. Adams HP Jr, del Zoppo G, Alberts MJ, et al; American Heart Association; American Stroke Association Stroke Council; Clinical Cardiology Council; Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention Council; Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease and Quality of Care Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Groups. Guidelines for the early management of adults with ischemic stroke: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council, Clinical Cardiology Council, Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention Council, and the Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease and Quality of Care Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Groups: the American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline as an educational tool for neurologists. Stroke 2007;38:1655–1711 PubMed 22. Swanson RA. Intravenous heparin for acute stroke: what can we learn from the megatrials? Neurology 1999;52:1746–1750 PubMed 23. Khamashta MA, Cuadrado MJ, Mujic F, Taub NA, Hunt BJ, Hughes GR. The management of thrombosis in the antiphospholipid-antibody syndrome. N Engl J Med 1995;332:993–997 PubMed 24. Adams HP Jr, del Zoppo G, Alberts MJ, et al; American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council; American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Clinical Cardiology Council; American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention Council; Athero-sclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease Working Group; Quality of Care Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Guidelines for the early management of adults with ischemic stroke: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council, Clinical Cardiology Council, Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention Council, and the Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease and Quality of Care Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Groups: The American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline as an educational tool for neurologists. Circulation 2007;115:e478–e534 PubMed 25. Chen HJ, Lee TC, Wei CP. Treatment of cerebellar infarction by decompressive suboccipital craniectomy. Stroke 1992;23:957–961 PubMed 26. Kudo H, Kawaguchi T, Minami H, Kuwamura K, Miyata M, Kohmura E. Controversy of surgical treatment for severe cerebellar infarction. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2007;16:259–262 PubMed 27. Gupta R, Connolly ES, Mayer S, Elkind MS. Hemicraniectomy for massive middle cerebral artery territory infarction: a systematic review. Stroke 2004;35:539–543 PubMed 28. Rieke K, Schwab S, Krieger D, et al. Decompressive surgery in space-occupying hemispheric infarction: results of an open, prospective trial. Crit Care Med 1995;23:1576–1587 PubMed 29. Schwab S, Steiner T, Aschoff A, et al. Early hemicraniectomy in patients with complete middle cerebral artery infarction. Stroke 1998;29:1888–1893 PubMed 30. Barnett HJ, Taylor DW, Eliasziw M, et al. Benefit of carotid endarterectomy in patients with symptomatic moderate or severe stenosis. North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators. N Engl J Med 1998;339:1415–1425 PubMed 31. Fisher CM, Karnes WE, Kubik CS. Lateral medullary infarction-the pattern of vascular occlusion. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1961;20:323–379 PubMed 32. Nelles G, Contois KA, Valente SL, et al. Recovery following lateral medullary infarction. Neurology 1998;50:1418–1422 PubMed

Stroke

References

Stroke

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree