57 Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

Clinical Vignette

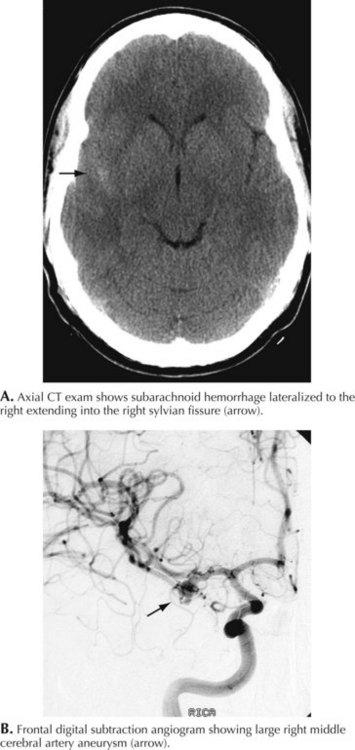

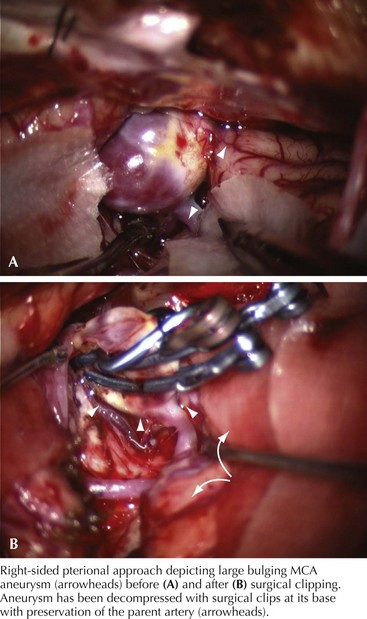

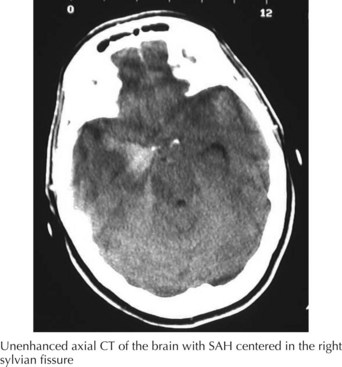

A 66-year-old woman suddenly experienced a terrible temporal pain radiating into her forehead. The headache was so severe that she almost lost consciousness. She became nauseated, vomited, and felt disoriented. Her family called emergency medical services and had her brought to the emergency room. There, she was noted to be arousable but sleepy and confused. She had nuchal rigidity, photophobia, but no focal motor deficit. An unenhanced head computed tomography (CT) showed subarachnoid hemorrhage centered in the right sylvian fissure but no brain parenchymal abnormalities. Angiography demonstrated a ruptured middle cerebral artery aneurysm that was successfully clipped the next morning. The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful (Figs. 57-1 and 57-2).

Clinical Vignette

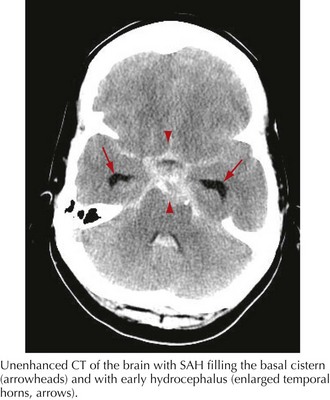

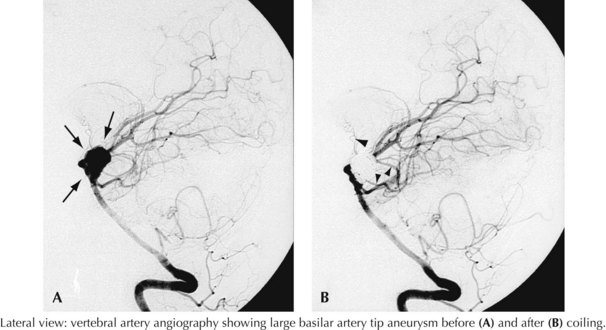

A 44-year-old postal worker presented with severe headache and nuchal rigidity to an emergency room. Unenhanced head CT revealed a subarachnoid hemorrhage centered in the basal cisterns, and further evaluation with catheter angiography revealed a large aneurysm arising from the basilar artery tip. After consultation between the neurosurgeon and the interventional neuroradiologist, the decision to perform endovascular coil embolization was made and the procedure was carried out successfully. The patient recovered fully after a 3-week hospital stay but required a second procedure after 6 months when follow-up angiography demonstrated a reexpansion of the neck of the aneurysm (Figs. 57-3 and 57-4).

Clinical Presentation

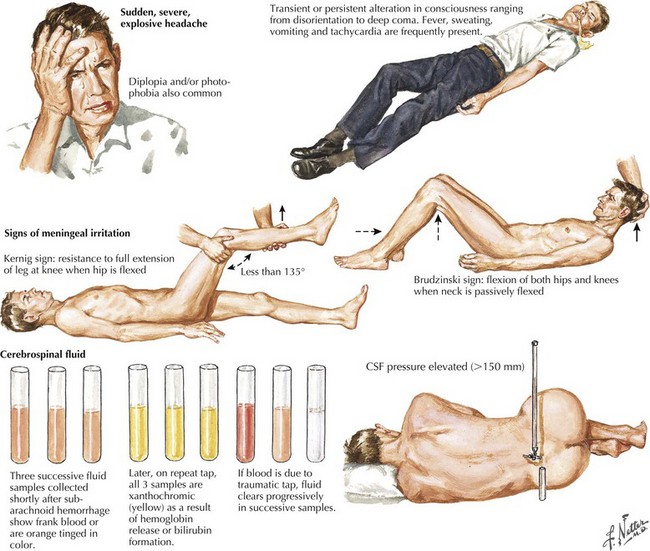

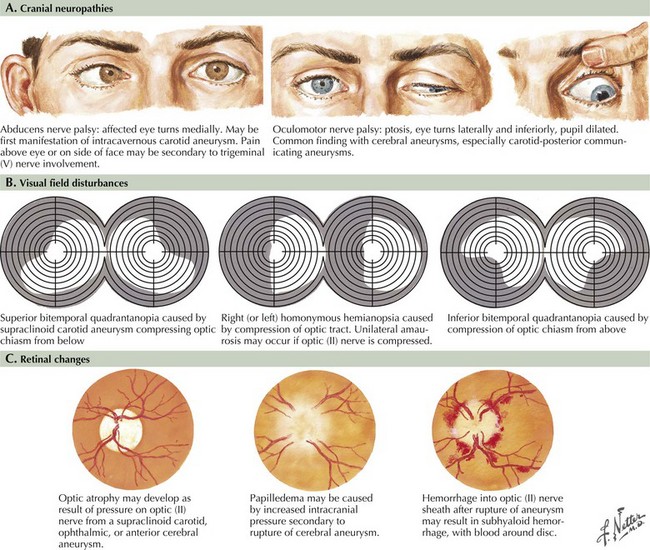

Seizure-like activity may be observed. The incidence of true seizure activity in patients with SAH is estimated at 20%. Seizures in SAH are most commonly associated with middle cerebral artery (MCA) and anterior communicating artery (ACA) aneurysmal rupture causing intracerebral hematomas. Unfortunately, many patients recall having a sentinel hemorrhage or warning leak with a fleeting but severe headache within the 2–3 weeks before the major ictus. This headache is somewhat milder and usually not associated with meningismus; it is often ignored until the catastrophic return of a major rupture. When evaluating patients with SAH or sudden severe headache, special attention should be focused on the level of consciousness, focal neurologic signs such as hemiparesis or cranial nerve palsies, and signs of meningismus (Fig. 57-5). Meningismus frequently occurs, associated with nuchal rigidity. Brudzinski’s maneuver is an excellent means of evaluating meningismus; the examiner flexes the patient’s neck, precipitating hip flexion, knee flexion, and hamstring pain. Diplopia (due to abducens or oculomotor nerve palsies) and visual loss (chiasmal or optic nerve involvement) are caused by either cranial nerve compression from the aneurysmal dome or aneurysmal rupture and increased intracranial pressure (Fig. 57-6).

Diagnostic Approach

The clinical diagnosis of SAH is best confirmed with brain CT (Fig. 57-7). Its sensitivity is highest in the first 24 hours after headache onset. A mild hemorrhage may wash away within 24 hours but approximately 50% of severe SAHs are still visible on CT 1 week after the ictus, and only one third are seen after 2 weeks. CT confirms the presence of SAH and frequently highlights associated issues such as hydrocephalus, intraparenchymal hematoma, intraventricular hemorrhage, or subdural hemorrhage.

Whenever the clinical suspicion of SAH exists but CT is negative, a lumbar puncture must be performed. A nontraumatic tap is crucial. When the presence of blood in the CSF does not clear between the first and fourth tubes, this is particularly suggestive of SAH (See Fig. 57-5). However, a more sensitive indicator is CSF xanthochromia, which represents lysis of erythrocytes with degradation of heme products into bilirubin within the CSF. This frequently renders the CSF a yellowish color within 1–3 hours after an SAH, and often persists for approximately 2–3 weeks.

To ensure proper communication, predict outcomes, and guide management, a clinical grade for each SAH is needed. Several grading scales are available; the most widely used is the Hunt–Hess scale—a five-tiered description of the patient’s state and an indicator of prognosis (Table 57-1).

Table 57-1 Hunt–Hess Grading Scale for Berry Aneurysms

| Grade | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Asymptomatic, or mild headache and slight nuchal rigidity |

| 2 | Moderate to severe headache, nuchal rigidity, no neurologic deficits other than cranial nerve palsies. |

| 3 | Mild focal deficit, lethargy, confusion |

| 4 | Stupor, hemiparesis, central neurologic signs |

| 5 |