Chapter 9 Summary of selected NMT associated modalities

A key difference between neuromuscular therapies (see page 192) – which this book describes – and neuromuscular technique (i.e. Lief’s or European NMT – see Box 9.3) is that the former incorporates under its’ definition, a host of complementary physical modalities – including Lief’s NMT. This chapter describes the range of physical modalities. It is worth noting that not all of these are ‘manual’, as they include hydrotherapy and, potentially, acupuncture and dry needling.

Box 9.3 European (Lief’s) neuromuscular technique (Chaitow 2010)

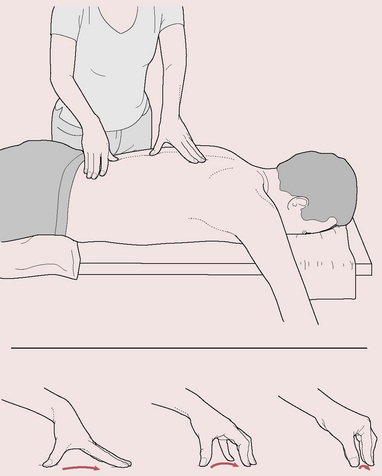

European NMT thumb technique

• The tip of the thumb can deliver varying degrees of pressure by using:

• In thumb technique application, the hand is spread for balance and control with the palm arched and with the tips of the fingers providing a fulcrum, the whole hand thereby resembling a ‘bridge’ (Fig. 9.2). The thumb freely passes under the bridge toward one of the finger tips.

Figure 9.2 NMT thumb technique: note static fingers provide fulcrum for moving thumb

(reproduced with permission from Chaitow & DeLany 2008).

• During a single stroke, which covers between 2 and 3 inches (5–8 cm), the finger tips act as a point of balance while the chief force is imparted to the thumb tip. Controlled application of body weight through the long axis of the extended arm focuses force through the thumb, with thumb and hand seldom imparting their own muscular force except when addressing small localized contractures or fibrotic ‘nodules’.

• The thumb, therefore, never leads the hand but always trails behind the stable fingers, the tips of which rest just beyond the end of the stroke.

• The hand and arm remain still as the thumb moves through the tissues being assessed or treated.

• The extreme versatility of the thumb enables it to modify the direction and degree of imparted force in accordance with the indications of the tissue being tested/treated. The practitioner’s sensory input through the thumb can be augmented with closed eyes so that every change in the tissue texture or tone can be noticed.

• The weight being imparted should travel in as straight a line as possible directly to its target, with no flexion of the elbow or the wrist by more than a few degrees.

• The practitioner’s body is positioned to achieve economy of effort and comfort. The optimum height of the table and the most effective angle of approach to the body areas being addressed should be considered (see Volume 1, Fig. 9.10)

• The nature of the tissue being treated will determine the degree of pressure imparted, with changes in pressure being possible, and indeed desirable, during strokes across and through the tissues. When being treated, a general degree of discomfort for the patient is usually acceptable but he should not feel pain.

• A stroke or glide of 2–3 inches (5–8 cm) will usually take 4–5 seconds, seldom more unless a particularly obstructive indurated area is being addressed. In normal diagnostic and therapeutic use the thumb continues to move as it probes, decongests and generally treats the tissues. If a myofascial trigger point is being treated, more time may be required at a single site for application of static or intermittent pressure.

• Since assessment mode attempts to precisely meet and match the tissue resistance, the pressure used varies constantly in response to what is being palpated.

• A greater degree of pressure is used in treatment mode and this will vary depending upon the objective, whether to inhibit neural activity or circulation, to produce localized stretching, to decongest and so on (see Volume 1, Box 9.4).

European NMT finger technique

• The middle or index finger should be slightly flexed and, depending upon the direction of the stroke and density of the tissues, should be supported by one of its adjacent members.

• The angle of pressure to the skin surface should be between 40° and 50°. A firm contact and a minimum of lubricant are used as the treating finger strokes to create a tensile strain between its tip and the tissue underlying it. The tissues are stretched and lifted by the passage of the finger which, like the thumb, should continue moving unless, or until, dense indurated tissue prevents its easy passage.

• The finger tip should never lead the stroke but should always follow the wrist, as the hand is drawn toward the practitioner, so that the entire hand moves with the stroke and elbow flexion occurs as necessary to complete the stroke. The strokes can be repeated once or twice as tissue changes dictate (see Volume 1, Box 14.8).

• The patient’s reactions must be taken into account when deciding the degree of force to be used.

• Transient pain or mild discomfort is to be expected. Most sensitive areas are indicative of some degree of associated dysfunction, local or reflexive, and their presence should be recorded.

• If tissue resistance is significant, the treating finger should be supported by another finger.

Variations

• superficial stroking in the direction of lymphatic flow

• direct pressure along or across the line of axis of stress fibers

• deeper alternating ‘make and break’ stretching and pressure or traction on fascial tissue

• sustained or intermittent ischemic (‘inhibitory’) pressure, applied for specific effects.

• The point should be marked and noted (on a chart and if necessary on the body with a skin pencil).

• Sustained ischemic/inhibitory pressure can be used.

• A positional release (PR) approach can be used to reduce activity in the hyperreactive tissue.

• Initiation of an isometric contraction followed by stretch (MET) could be applied.

• A combination of pressure, PRT and MET (integrated neuromuscular inhibition technique – INIT) can be introduced.

• Spray-and-stretch methods can be used.

• An acupuncture needle or a procaine injection can be used if the practitioner is duly licensed and trained.

The global view

In this text, we have considered a number of features that are all commonly involved in causing or intensifying pain (Chaitow 2010). While it is simplistic to isolate factors that affect the body – globally or locally – it is also necessary at times to do this. We have presented models of interacting adaptations to stress, resulting from postural, emotional, respiratory and other factors, which have fundamental influences on health and ill health.

• biomechanical (postural dysfunction, upper chest breathing patterns, hypertonicity, neural compression, trigger point activity, etc.)

• biochemical (nutrition, ischemia, inflammation, hormonal, hydration, hyperventilation effects)

• psychosocial (stress, anxiety, depression, hyperventilation tendencies).

While these health factors have tremendous potential to interface with one another, each may at times also be considered individually. It is important to address whichever of these influences on musculoskeletal pain can be identified in order to remove or modify as many etiological and perpetuating influences as possible (Simons et al 1999); however, it is crucial to do so without creating further distress or requirement for excessive adaptation. When appropriate therapeutic interventions are used, the body’s adaptation response produces beneficial outcomes. When excessive or inappropriate interventions are applied, the additional adaptive load inevitably leads to a worsening of the patient’s condition. Treatment is a form of stress and can have a beneficial or a harmful outcome depending on its degree of appropriateness. When patients report post-treatment symptoms of headache, nausea, achiness or fatigue, they are often told it is a ‘healing crisis’. Whether ‘healing’ or not, it is a ‘crisis’ all the same and often avoidable if basic measures are taken to reduce excessive adaptation responses to treatment by managing the amount and type of treatment offered.

Selecting an adequate degree of therapeutic intervention in order to catalyze a change, without overloading the adaptive mechanisms, is something of an art form. When analytical clinical skills are weak or details of techniques unclear, results may be unpredictable and unsatisfactory (DeLany 1999). Whereas, when such skills are effectively utilized and intervention methodically applied involving a manageable load, the outcome is more likely to be a sequential recovery and improvement.

• Hyperventilation modifies blood acidity, alters neural reporting (initially hyper and then hypo), creates feelings of anxiety and apprehension and directly impacts on the structural components of the thoracic and cervical region, both muscles and joints (Gilbert 1998). If better breathing mechanics can be restored by addressing the musculature that controls inhalation and exhalation, emotional stability (regarding grief, fear, anxiety, etc.) may be enhanced and better breathing techniques employed, so that all that depends upon the breath (and what does not?) has potential for (often significant) improvement.

• Altered chemistry (hypoglycemia, alkalosis, etc.) affects mood directly while altered mood (depression, anxiety) changes blood chemistry, as well as altering muscle tone and, by implication, trigger point evolution (Pryor & Prasad 2002, Brostoff 1992). Therefore, addressing dietary intake, digestion and/or assimilation could result in significant changes in soft tissue conditions as well as psychological well-being, which may influence postural function.

• Altered structure (posture, for example) modifies function (breathing, for example) and therefore impacts on blood biochemistry (e.g. O2: CO2 balance, circulatory efficiency and delivery of nutrients, etc.), which impacts on mood (Foster et al, 2001). Stretching protocols, soft tissue or skeletal manipulations and ergonomically sound changes in patterns of use, all serve to restore structural alignment, which positively influences all other bodily functions.

A home care program can be designed appropriate to the needs and current status of the patient, for both physical relief of the tissues (stretching, self-help methods, hydrotherapies see Chapter 7) and awareness of perpetuating factors (postural habits, work and recreational practices, nutritional choices, stress management). Lifestyle changes are essential if influences resulting from habits and potentially harmful choices made in the past are to be reduced (see notes on concordance in Volume 1, Chapter 8)

The purpose of this chapter

The treatment methods offered in the techniques portion of this text are NMT (both American version ™and European style), muscle energy techniques (MET), positional release techniques (PRT), myofascial release (MFR) and a variety of modifications and variations of these and other supporting modalities that can be usefully interchanged, and/or combined. This is not meant to suggest that methods not discussed in this text (for example, high-velocity thrust methods and joint mobilization), which to an extent address soft tissue dysfunction, are less effective or inappropriate. It does, however, mean that the methods described throughout the clinical applications section are known to be helpful as a result of our clinical experience. Traditional massage methods are also frequently mentioned (see Box 9.1), as are applications of lymphatic drainage techniques (see Box 9.2). All these methods require appropriate training and any descriptions offered in this chapter are not meant to replace that requirement.

Box 9.1 Traditional massage techniques

• Effleurage: a gliding stroke used to induce relaxation and reduce fluid congestion by encouraging venous or lymphatic fluid movement toward the center. Lubricants are usually used.

• Petrissage: a wringing and stretching movement that attempts to ‘milk’ the tissues of waste products and assist in circulatory interchange. The manipulations press and roll the muscles under the hands.

• Kneading: a compressive stroke that alternately squeezes and lifts the tissues to improve fluid exchange and achieve relaxation of tissues.

• Inhibition: application of pressure directly to the belly or attachments of contracted muscles or to local soft tissue dysfunction for a variable amount of time or in a ‘make-and-break’ (pressure applied and then released) manner, to reduce hypertonic contraction or for reflexive effects. Also known as ischemic compression or trigger point pressure release.

• Vibration and friction: small circular or vibratory movements, with the tips of fingers or thumb, particularly used near origins and insertions and near bony attachments to induce a relaxing effect or to produce heat in the tissue, thereby altering the gel state of the ground substance. Vibration can also be achieved with mechanical devices with varying oscillation rates that may affect the tissue differently.

• Transverse friction: a short pressure stroke applied slowly and rhythmically along or across the belly of muscles using the heel of the hand, thumb or fingers.

Massage effects explained

A combination of physical effects occur, apart from the undoubted anxiety-reducing influences (Sandler 1983), which involve a number of biochemical changes.

• Plasma cortisol and catecholamine concentrations alter markedly as anxiety levels drop and depression is also reduced (Field 1992).

• Serotonin levels rise as sleep is enhanced, even in severely ill patients – preterm infants, cancer patients and people with irritable bowel problems as well as HIV-positive individuals (Acolet 1993, Ferel-Torey 1993, Ironson 1993, Weinrich & Weinrich 1990).

• Pressure strokes tend to displace fluid content, encouraging venous, lymphatic and tissue drainage.

• Increase of fresh oxygenated blood flow aids normalization via increased capillary filtration and venous capillary pressure.

• Edema is reduced, as are the effects of pain-inducing substances that may be present (Hovind 1974, Xujian 1990).

• Decreases the sensitivity of the gamma-efferent control of the muscle spindles and thereby reduces any shortening tendency of the muscles (Puustjarvi 1990).

• Provokes a transition in the ground substance of fascia (the colloidal matrix) from gel to sol, which increases internal hydration and assists in the removal of toxins from the tissue (Oschman 1997).

• Pressure techniques can have a direct effect on the Golgi tendon organs, which detect the load applied to the tendon or muscle.

A more in-depth discussion of massage techniques is found in Volume 1.

Box 9.2 Lymphatic drainage techniques

Lymphatic drainage, which can be assisted by coordination with the patient’s breathing cycle, enhances fluid movement into the treated tissue, improving oxygenation and the supply of nutrients to the area. Practitioners trained in advanced lymph drainage can learn to accurately follow (and augment) the specific rhythm of lymphatic flow (Chikly 1999). With sound anatomical knowledge, specific directions of drainage can be plotted, usually toward the node group responsible for evacuation of a particular area (lymphotome). Hand pressure used in lymph drainage should be very light indeed, less than an ounce (28 g) per cm2 (under 8 oz per square inch), in order to encourage lymph flow without increasing blood filtration (Chikly 1999).

The methods of stretching described in this text are largely based on osteopathic MET methodology, and carry the endorsement of David Simons (Simons et al 1999) as well as some of the leading experts in rehabilitation medicine (Lewit 1999, Liebenson 2007). Some stretching approaches are described in Chapter 7 with self-help strategies.

The remainder of this chapter briefly reviews these primary and supporting modalities. It is strongly suggested that the reader also review Volume 1, Chapters 9 and 10, for more in-depth discussions of these methods and modalities.

General application of neuromuscular techniques

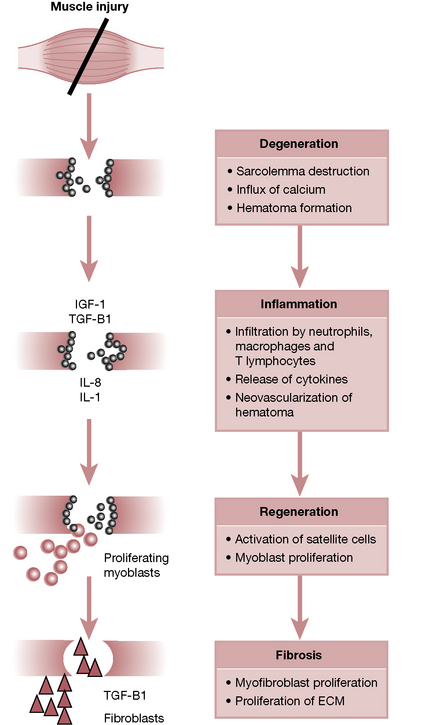

Following trauma, the involved myofibers undergo four interrelated, time dependent phases: degeneration, inflammation, regeneration, and fibrosis (Gates & Huard 2005). See Figure 9.1.

Figure 9.1 Phases of muscle healing after injury.

From Gates C Huard J 2005 Management of Skeletal Muscle Injuries in Military Personnel. Oper Tech Sports Med 13: Fig 1, p. 248.

Since NMT techniques tend to increase blood flow and reduce spasms, most are contraindicated in the initial stages of acute injury (72–96 hours post trauma) when a natural inflammatory process commences and blood flow and swelling should be reduced, rather than stimulated. Connective tissues damaged by the trauma therefore need time to repair, and the recovery process often results in splinting and swelling (Cailliet 1996).

NMT for chronic pain

It is important to remember that it is the degree of current pain and inflammation that defines the stage of repair (acute, subacute, chronic) the tissue is in, not just the length of time since the injury. Once acute inflammation subsides, which can take weeks, a number of rehabilitation stages of soft tissue therapy are suggested in the order listed below. Chaitow & DeLany (2008) note that these modalities should be incorporated when the tissue is prepared for them, which may be immediately for some patients or a matter of weeks or even months for others. They define these as application of:

1. manual tissue mobilization techniques – appropriate soft tissue techniques aimed at decreasing spasm and ischemia, enhancing drainage of the soft tissues and deactivating trigger points

2. stretching – appropriate active, passive and self-applied stretching methods to restore normal flexibility

3. mild tissue toning – appropriately selected forms of exercise to restore normal tone and strength

4. conditioning exercises and weight-training approaches – to restore overall endurance and cardiovascular efficiency

5. restoring normal proprioceptive function and coordination – by use of standard rehabilitation approaches

6. improving posture and body use – with a particular aim of restoring normal breathing patterns.

Chaitow & DeLany (2008) emphasize:

Palpation and treatment

Though the order of the protocols listed in this text can be varied to some degree, there are some suggestions which have proven to be clinically imperative. These are based on our clinical experience (and of those experts cited in the text) and are suggested as a general guideline when addressing most myofascial tissue problems. Chaitow & DeLany (2008) suggest the following:

• If a frictional effect is required (for example, in order to achieve a rapid vascular response) then no lubricant should be used. In most cases, dry skin work is employed before lubrication is applied to avoid slippage of the hands on the skin.

• The use of a lubricant is often needed during NMT application to facilitate smooth passage of the thumb or finger. It is important to avoid excessive oiliness or the essential aspect of slight digital traction will be lost.

• Before the deeper layers are addressed, the most superficial tissue is softened and, if necessary, treated.

• The proximal portions of an extremity are addressed (‘softened’) before the distal portions are treated, thereby reducing restrictions to lymphatic flow before distal lymph movement is increased.

• In a two-jointed muscle, both joints are assessed. For instance, if gastrocnemius is examined, both the knee and ankle joints are considered. In multijointed muscles, all involved joints are assessed.

• Knowledge of the anatomy of each muscle (innervation, fiber arrangement, nearby neurovascular structures and all overlying and underlying muscles) will greatly assist the practitioner in quickly locating the appropriate muscles and their trigger points.

• Where multiple areas of pain are present, our experience suggests the following.

• Treat the most proximal, most medial and most painful trigger points (or areas of pain) first.

• Avoid overtreating the individual tissues as well as the structure as a whole.

• Fewer than five active trigger points should be treated at any one session if the person is frail or demonstrating symptoms of fatigue and general susceptibility as this might place an adaptive load on the individual that could prove extremely stressful.

When digital pressure is applied to tissues, a variety of effects are simultaneously occurring.

1. Temporary interference with circulatory efficiency results in a degree of ischemia, which will reverse when pressure is released (Simons et al 1999).

2. Constantly applied pressure produces a sustained barrage of afferent, followed by efferent, information, resulting in neurological inhibition (Ward 1997).

3. As the elastic barrier is reached and the process of ‘creep’ commences, the tissue is mechanically stretched (Cantu & Grodin 1992).

4. Colloids change state when shearing forces are applied, thereby modifying relatively gel tissues toward a more sol-like state (Athenstaedt 1974, Barnes 1996).

5. Interference with pain messages reaching the brain is apparently caused when mechanoreceptors are stimulated (gate theory) (Melzack & Wall 1988).

6. Local endorphin release is triggered along with enkephalin release in the brain and CNS, as well as the adrenal medulla (Baldry 2005).

7. Endocannabinoids are released. These, like the better known endorphin and enkephalin systems, dampen nociception and pain, and decrease inflammation in myofascial tissues (McPartland 2008).

8. A rapid release of the taut band associated with trigger points often results from applied pressure (Simons et al 1999).

9. Acupuncture and acupressure concepts associate digital pressure with alteration of energy flow along hypothesized meridians (Chaitow 1990).

Neuromuscular therapy: american version

In this text, the American version of NMT is offered as a foundation for developing palpatory skills and treatment techniques while the European version accompanies it to offer an alternative approach (see Box 9.3). Emerging from diverse backgrounds, these two methods of NMT have similarities as well as differences in application. Volume 1, Chapter 9 discusses the history of both methods and their similarities as well as the characteristics unique to each.

NMT American version™, as presented in these textbooks, attempts to address (or at least consider) a number of features commonly involved in causing or intensifying pain (Chaitow 2010). These include, among others, the following factors which affect the whole body:

• nutritional imbalances and deficiencies

• toxicity (exogenous and endogenous)

• stress (physical or psychological)

• posture (including patterns of use)

as well as locally dysfunctional states such as:

Gliding techniques

• The practitioner’s fingers (which stabilize) are spread slightly and ‘lead’ the thumbs (which are the actual treatment tool in most cases). The fingers support the weight of the hands and arms, which relieves the thumbs of that responsibility so that they are more easily controlled and can vary induced tension to match the tissues. (See Fig. 10.32, p. 257.)

• When two-handed glides are employed, the lateral aspects of the thumbs are placed side by side or one slightly ahead of the other with both pointing in the direction of the glide (see Volume 1, Fig. 9.2A)

• The hands move as a unit, with little or no motion taking place in the wrist or the thumb joints, which otherwise may result in joint inflammation, irritation and dysfunction.

• Pressure is applied through the wrist and longitudinally through the thumb joints, not against the medial aspects of the thumbs, as would occur if the gliding stroke were performed with the thumb tips touching end to end (see Volume 1, Fig. 9.2B)

• As the thumb or fingers move from normal tissue to tense, edematous, fibrotic or flaccid tissue, the amount of pressure required to ‘meet and match’ it will vary, with pressure being increased only if appropriate. As the thumb glides transversely across taut bands, indurations may be more defined.

• Nodules are sometimes embedded (usually at mid-fiber range) in dense, congested tissue and as the state of the colloidal matrix softens from the gliding stroke, distinct palpation of the nodules becomes clearer (see Box 9.4).

• The practitioner moves from trigger point pressure release, to various stretching techniques, heat or ice, vibration or movements, while seamlessly integrating these with the assessment strokes.

• The gliding strokes are applied repetitively (6–8 times), then the tissues are allowed to rest while working elsewhere before returning to reexamine them.

• Positional release methods, gentle myofascial release, cryotherapy, lymph drainage or other antiinflammatory measures would be more appropriate for tender or inflamed tissues than friction, heat, deep gliding strokes or other modalities that might increase an inflammatory response.

• The gliding stroke should cover 3–4 inches per second unless the tissue is sensitive, in which case a slower pace and reduced pressure are suggested. It is important to develop a moderate gliding speed in order to feel what is present in the tissue. Rapid movement may skim over congestion and other changes in the tissues or cause unnecessary discomfort while movement that is too slow may displace tissue and make identification of individual muscles difficult.

• Unless contraindicated due to inflammation, a moist hot pack can be placed on the tissues between gliding repetitions to further enhance the effects. Ice may also be used and is especially effective on attachment trigger points (see Box 9.5) where a constant concentration of muscle stress tends to provoke an inflammatory response (Simons et al 1999). See Box 9.6 for information regarding use of hydrotherapy methods and a more in-depth discussion in Volume 1, Chapter 10.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree