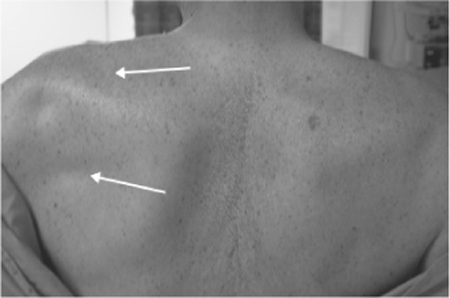

17 Suprascapular Nerve Palsy A 66-year-old, right-handed man presented to the clinic with a long history of bilateral shoulder pain. Over the years, his family doctor had provided him with intermittent injections of cortisone into his painful shoulders. Although this was symptomatically helpful for a time, the patient’s pain would always return. More recently, he was referred to an orthopedic surgeon who gave him a cortisone injection in the left supraclavicular area. Following this injection, the patient noted a reduction in his active range of motion at the left shoulder and gradually worsening pain. Over the subsequent 2 years, the patient reported progressive weakness of left shoulder abduction and had noticed increasing atrophy of the muscles behind his left scapula. Aside from periodic shoulder pain, the patient reported no other sensory abnormalities, paresthesias, or dysesthesias, and no other neurological deficits. His bladder and bowel functions were normal, as was his gait. On examination, the patient exhibited a full range of motion at the neck. Atrophy of the infraspinatus and supraspinatus muscles on the left side was evident (Fig. 17–1). Power was 1/5 during external rotation at the left shoulder, compatible with dysfunction of the left infraspinatus muscle. Power was 3/5 during abduction of the left upper extremity, compatible with dysfunction of the left supraspinatus muscle. The rest of the neurological exam was normal. Electromyography and nerve conduction studies revealed abnormalities in the distribution of the left supra-scapular nerve. Figure 17–1 White arrows indicating atrophy of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles. Suprascapular neuropathy The suprascapular nerve is composed of fibers from the fifth and sixth, and sometimes fourth, cervical roots. It provides motor innervation to the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles. It also provides sensory innervation to the coracohumeral and coracoacromial ligaments, the subacromial bursa, and the acromioclavicular and gleno-humeral joints. A sensory cutaneous branch innervating the proximal and lateral aspects of the upper extremity has been described but is seldom present. From its origin at the superior trunk of the brachial plexus, the suprascapular nerve runs laterally parallel to the omohyoid muscle and deep to the trapezius muscle. It enters the supraspinous fossa with the suprascapular artery and vein and sends motor branches to the supraspinatus muscle. It then travels through the suprascapular notch inferior to the transverse scapular ligament. Unlike the nerve, the artery and vein travel above the transverse scapular ligament. At the level of the transverse scapular ligament, the suprascapular nerve typically gives off sensory filaments to the coracohumeral and coracoacromial ligaments, the subacromial bursa, and the acromioclavicular joint. The suprascapular nerve then runs deep to the supraspinatus muscle and curves around the lateral border of the scapular spine with its accompanying vessels inferomedial to the spinoglenoid ligament. Once through this spinoglenoid notch, the nerve enters the infraspinous fossa sending motor fibers to the infraspinatus muscle and sensory filaments to the glenohumeral joint. Suprascapular neuropathy can occur at any age but is most common among people between 20 and 50 years old. Men present with this condition more often than women. Either side may be affected, but the condition is more common on the patient’s dominant side. There is occasionally a significant precipitating event, but more commonly, the onset is insidious. The condition is more common among people who engage in repetitive overhead movements, such as volleyball players. The most common symptom is a dull, aching pain in the posterior aspect of the shoulder exacerbated by overhead movements (Table 17–1). Pain is less prominent with distal lesions because most of the sensory fibers are distributed proximally in the supraspinous fossa. Weakness of the affected shoulder is another common symptom, sometimes unaccompanied by pain. In particular, weakness of abduction, related to supraspinatus muscle involvement, and weakness of external rotation, related to infraspinatus involvement, often occur. A common sign of supra-scapular neuropathy is wasting of the involved posterior scapular muscles (Fig. 17–1). In fact, muscular atrophy is sometimes the main reason that patients with this condition present to physicians. In addition to muscle wasting, another sign of suprascapular neuropathy is tenderness to palpation. With a proximal lesion, tenderness may be elicited between the clavicle and scapular spine. More distal lesions may be associated with tenderness at the spino-glenoid notch. There are several reasons that suprascapular nerve palsy may occur. The suprascapular nerve can be injured as a result of trauma. For example, scapular or clavicular fracture, shoulder dislocations, or penetrating trauma can all produce acute suprascapular nerve injury. Repetitive overuse is a more subtle form of trauma that may lead to suprascapular neuropathy. Repetitive overuse can contribute to suprascapular neuropathy directly through stretching of the nerve, or indirectly through ligamentous hypertrophy, which then compresses the nerve. The suprascapular and spinoglenoid notches are the two most common sites of suprascapular nerve compression and entrapment.

Case Presentation

Case Presentation

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Anatomy

Anatomy

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

| Dull, aching shoulder pain (worse with overhead movements) |

| Weakness of shoulder abduction and external rotation |

| Posterior scapular muscle (spinati) atrophy |

Besides ligamentous hypertrophy, mass lesions, such as ganglion cysts, bone cysts, synovial sarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, chondrosarcoma, metastatic renal cell carcinoma, or hematoma, may underlie suprascapular nerve palsy. Finally, suprascapular neuropathy may be due to iatrogenic causes. For example, the suprascapular nerve may be injured during shoulder operations, or as in the case described here, following injections in the area of the suprascapular nerve.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Many conditions share certain clinical features with suprascapular neuropathy. For this reason, it is important to consider a broad array of clinical entities in the differential diagnosis of suprascapular nerve palsy. Degenerative cervical spine disease, cervical radiculopathy (particularly C5 radiculopathy), brachial plexopathy, thoracic outlet syndrome, Pancoast tumor, bicipital tenosynovitis, subacromial bursitis, rotator cuff tear, rotator cuff tendonitis, adhesive capsulitis, and other glenohumeral pathology are all in the differential diagnosis of suprascapular neuropathy.

Diagnostic Tests

Diagnostic Tests

Diagnostic tests can help to provide confirmation for the presence of suprascapular neuropathy or insight into its cause. One such test is the injection of local anesthetic into the suprascapular notch. The rationale for this test is that if suprascapular nerve irritation or impingement underlies the patient’s sensory symptoms, then local anesthetic injected around the nerve should relieve those symptoms. Although often effective in relieving the sensory symptoms of suprascapular neuropathy, this test will also provide sensory relief for many other problems affecting the shoulder. As such, this test is not very specific for supra-scapular neuropathy. In contrast, nerve conduction tests and electromyography can be targeted to identify and localize suprascapular nerve pathology. Therefore, these electrodiagnostic tests are commonly included in the workup of patients suspected of having suprascapular neuropathy. Electromyographic findings of denervation of the infraspinatus, less often the supraspinatus, are diagnostic.

Plain radiographs are useful to rule out bony abnormalities in the shoulder that may produce suprascapular nerve impingement. Another useful imaging modality is ultrasound. Ultrasound can help to identify mass lesions compressing the nerve. However, the best method for evaluating soft tissue lesions (such as ganglion cysts) around the shoulder is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). We recommend the use of MRI in all patients presenting with infraspinatus involvement alone, because of the high incidence of ganglion cysts in the splenoglenoid notch, under

Management Options

Management Options

In the management of suprascapular neuropathy, non-operative and surgical approaches can be employed. The most basic and often effective nonoperative approach is the avoidance of activity that aggravates the pain and nerve injury. Usually this entails limiting overhead movements with the affected limb. In addition to the avoidance of aggravating activity, flexibility exercises and then the gradual integration of shoulder girdle strengthening exercise can be useful. Mild analgesics and anti-inflammatories can also provide some symptomatic relief. Nonoperative management is usually given 3 to 6 months to show an effect.

The indications for surgical intervention are somewhat controversial (Table 17–2). Some suggest that all supra-scapular neuropathies should be given an initial trial of nonoperative management. Others believe that nonoperative management should be reserved for minor or incomplete injuries with no muscle atrophy and no known compressive lesion. A recent review of the outcome literature recommends an initial trial of nonoperative management for all cases secondary to overuse or stretching, and early surgery for cases secondary to a compressive lesion. It seems reasonable to recommend surgical intervention for cases that persist despite nonoperative management or that are known to be secondary to a compressive or space-occupying lesion. Additionally, some recommend that patients experiencing severe intractable pain should be offered early surgery.

Surgical Treatment

Surgical Treatment

A variety of surgical approaches may be employed to treat suprascapular neuropathy depending on the nature and location of the lesion. A common site of impingement is at the suprascapular notch due to compression from the transverse scapular ligament. When the injury is at the suprascapular notch with no evidence of mass lesion, surgical treatment involves releasing the nerve by transecting the transverse scapular ligament using a posterior approach. This was the approach used in the case described here (Figs. 17–2 and 17–3).

| Failed nonoperative management |

| Presence of a compressive or mass lesion |

| Severe, intractable pain |

The patient is placed in the prone position with head supported by a horseshoe brace. Important anatomical landmarks such as the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles, the scapular spine, the medial margin of the scapula, and the spinous processes are marked out preoperatively (Fig. 17–2). A transverse incision is made parallel to and 2 cm above the scapular spine. The trapezius muscle is divided with the use of blunt dissection parallel to the direction of its fibers. The supraspinatus muscle is then identified and divided in a similar fashion. Next, the suprascapular vessels are identified in their course above the transverse scapular ligament. The suprascapular nerve can then be seen running along the lateral aspect of the omohyoid muscle and then into the suprascapular notch beneath the transverse scapular ligament (Fig. 17–3A). A small, flat dissector or Lauer forceps is then passed over the nerve and beneath the transverse scapular ligament. The ligament can then be transected safely with a scalpel. Once the ligament has been transected, the nerve often bulges up significantly, revealing the considerable extent of its previous compression (Fig. 17–3B).

A less common site of compression is at the spino-glenoid notch. With this type of entrapment, a spinoglenoid decompression is required. To expose the nerve on the superior side of the spinoglenoid notch, the supraspinatus muscle is reflected superiorly. To expose the inferior side of the spinoglenoid notch, the deltoid muscle may be split in line with its fibers or partially detached from the spine of the scapula. The infraspinatus muscle is then reflected inferiorly, exposing the suprascapular nerve and vessels. With a distal lesion, it is important to assess the anatomy of the spinoglenoid notch for structures that may be compressing the nerve—specifically, the spinoglenoid ligament, scapular spine, or medial tendinous margin of the rotator cuff. Compression at this site may be addressed by transecting the spinoglenoid ligament and deepening the lateral margin of the scapular spine. Care must be taken when deepening the lateral margin to prevent weakening of the acromiospinous complex.

When the suprascapular nerve is injured secondary to compression by a cystic mass lesion, for example, a ganglion cyst, ultrasound or computed tomographically guided aspiration can be used. Alternatively, open resection of cystic or solid mass lesions can be effective. For those trained in its use, arthroscopy may be employed for decompression of those lesions that extend into the intraarticular space.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree