Supratentorial Nonglial Hemispheric Neoplasms

Supratentorial non-midline tumors of nonglial origin are a diverse group of neoplasms and constitute a substantial proportion of all childhood brain tumors. The incidence of those that are not glial in origin (i.e., astrocytomas, ependymomas, others) is difficult to assess, which is due, in part, to our evolving understanding of the molecular infrastructure of these tumors, their postulated cells of origin, and—ultimately—one’s definition of what is a glial versus a nonglial tumor. For example, should gangliocytomas be considered neural or glial tumors? Supratentorial tumors in general represent 22 to 54% of all pediatric brain tumors, and of these, about half are glial in origin; the remaining nonglial tumors are an interesting collection of many different types of pediatric brain tumors.1–5 Primitive neuroectodermal tumors (PNETs) represent about 5 to 10%, as do gangliogliomas, whereas other tumors occur in the 1 to 2% range and include choroid plexus papillomas/carcinomas (CPPs/CPCs), teratomas, dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumors (DNETs), meningiomas, germinomas (excluding those in pineal and suprasellar locations), sarcomas/chondromas, metastatic lesions, and lymphomas. Again, accurate statistics are difficult to obtain as these data are gleaned from case reports and from parts of larger mixed-case series. Nonetheless, unusual tumors occur in the supratentorial location and should be considered while treatment is being planned.1–3,5,6

This chapter focuses on the main nonglial hemispheric tumors, including PNET, ganglioglioma/gangliocytoma/desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma, DNET, CPP/CPC, meningioma, and—briefly—other rare tumors, such as central neurocytoma, germ cell tumors, metastatic malignancies and lymphoma.

35.1 Supratentorial Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumors

Supratentorial PNET is a relatively rare but challenging diagnosis that accounts for approximately 2.5 to 6% of all pediatric tumors.7 These tumors have a propensity for rapid growth, and thus the duration of symptoms is usually relatively short. The symptoms often include nonlateralizing signs of elevated intracranial pressure. Compared with medulloblastoma (the infratentorial equivalent of supratentorial PNET), supratentorial PNET has consistently demonstrated a worse prognosis, with 5-year survival rates ranging from 30 to 75% despite maximal therapy.7–12 These rates suggest an intrinsic biological difference between supratentorial and infratentorial PNETs.13 Originally, the etiologic cell of origin for PNETs was considered to be a primitive neuroepithelial cell capable of differentiating into neuronal, glial, and ependymal cell lines. The expression of SOX2, NOTCH1, and ID1 is upregulated and the JAK/STAT3 pathway is activated in supratentorial PNET, indicating a glial tumorigenesis. Conversely, the activation of proneural bHLH transcription factors is upregulated in infratentorial PNET, indicating a neuronal tumorigenesis.14–16

35.1.1 Imaging and Preoperative Evaluation

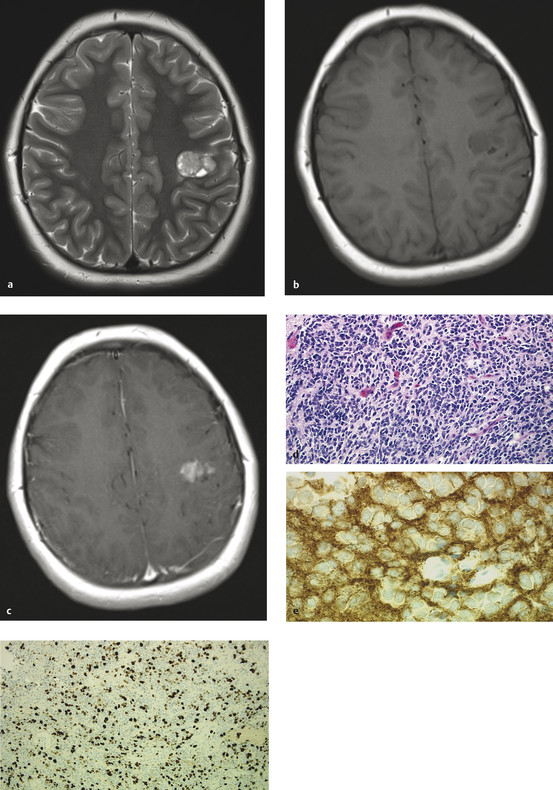

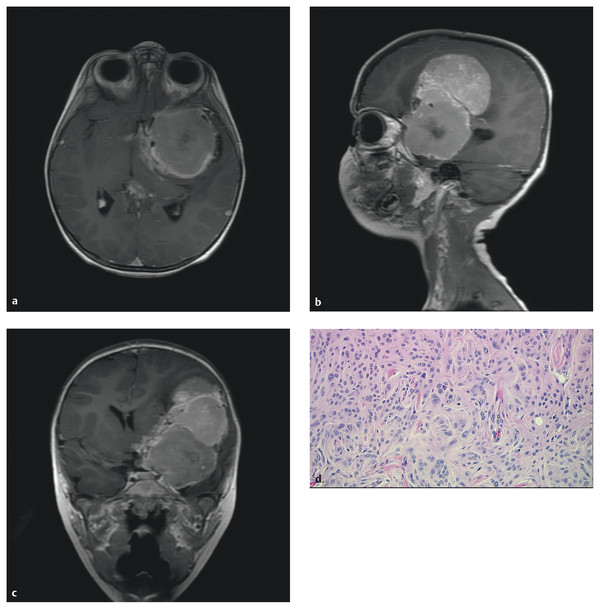

PNETs are generally hyperdense on computed tomography (CT) and isointense (or hypointense) to brain on magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, with avid—but often heterogeneous—enhancement (▶ Fig. 35.1). A recent study of PNETs in children (i.e., patients younger than 20 years of age) suggests that there is about a 15 to 20% incidence of nonenhancement. The center of the tumor is often heterogeneous, with cysts and/or areas of necrosis.17–19

Fig. 35.1 (a) Axial T2 magnetic resonance (MR) imaging and T1 MR imaging (b) with and (c) without contrast of a typically appearing supratentorial primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET) in a 9-year-old girl with classic Jacksonian seizures. The tumor is hyperintense on T2 with associated cystic areas. Heterogeneous enhancement is present after gadolinium administration. (d) Supratentorial PNET is hypointense to isointense on T1 imaging without contrast Hematoxylin and eosin stain (x20) (e) shows a patternless sheet of small cells with positive reactivity to synatophysin antibodies, (f) indicative of neuronal differentiation and a high rate of cellular proliferation (antibody to Ki-67 protein).

Staging should be performed preoperatively by imaging the entire neuraxis. At initial presentation, 10 to 20% of patients will have disseminated disease.9,20–22 Lack of dissemination by imaging should be confirmed by cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) cytology analysis, but this is usually done postoperatively once the mass lesion has been removed.23

35.1.2 Treatment and Outcome

PNET requires multimodal therapy, including surgical extirpation, craniospinal irradiation, and chemotherapy. Traditionally, all patients with supratentorial PNET were categorized as having high-risk disease, and survival rates have been less than 50% in most studies. Recently a multi-institutional group has stratified patients into average- and high-risk groups based on the following: age younger than 3 years, subtotal resection (i.e., more than 1.5 cm2 residual), and leptomeningeal dissemination.24 Patients without these risk factors are termed “average risk”; the presence of any one of these factors will place a patient in the “high-risk” category. When this stratification and treatment with risk-adjusted craniospinal irradiation with additional radiation to the primary tumor site and subsequent high-dose chemotherapy supported by stem cell rescue are used, the 5-year survival outcomes are 60% for high-risk patients and 75% for average-risk patients.

In general, patients should undergo maximal safe tumor resection, high-dose radiation to the tumor bed, some form of craniospinal radiation (± risk adjustment), and subsequent chemotherapy (± stem cell rescue).7–9,12,24–29 There are efforts under way to treat patients with resection and chemotherapy alone in order to delay, or altogether avoid, the potential costs of radiotherapy (RT), particularly in patients younger than 5 years of age.30 Rates of 5-year event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS) were 39% total for high- and low-risk patients (24% for high-risk patients, 53% for average-risk patients), and 49% total for high-and low-risk patients (33% for high-risk patients, 62% for average-risk patients), respectively. In this study, patients with nonpineal supratentorial PNET had a survival advantage over patients with pineal PNET. For patients with RT-naïve, chemoresponsive recurrences, myeloablative doses of thiotepa-based chemotherapy followed by stem cell rescue and RT may still offer the chance of cure.31

35.2 Glioneuronal Tumors: Gangliogliomas/Gangliocytomas/Desmoplastic Infantile Gangliogliomas

The tumors in this group have subtle differences but are considered together under the term ganglioglioma; where significant differences exist, they are detailed. Gangliogliomas are mixed neuronal–glial tumors and account for 4 to 9% of childhood brain tumors; patients often present with seizures, and these tumors account for up to 40% of all tumors responsible for epilepsy.32–40 In 1926, the term ganglioglioma was coined by O. C. Perkins for tumors composed of dysplastic neurons and neoplastic glia.41 Although the majority are cystic, temporal tumors in other locations are reported.33,34,40,42–44 The World Health Organization (WHO) considers them grade I or II, although anaplasia, necrosis, or an MIB labeling index above 10% can result in an upgrade to anaplastic (III) or malignant (IV).45

Desmoplastic infantile gangliogliomas (DIGs) are typically very large lesions arising in the hemispheres, generally in infants. They are often misdiagnosed as malignant astrocytomas or sarcoma-type tumors because of their cellular appearance and mitotic activity.46,47 They have a desmoplastic stroma, neoplastic astrocytes and neuronal cells, and may have a high mitotic or Ki-67 indices or areas of necrosis. Despite this more malignant picture, these tumors are WHO grade I.48

35.2.1 Imaging and Preoperative Evaluation

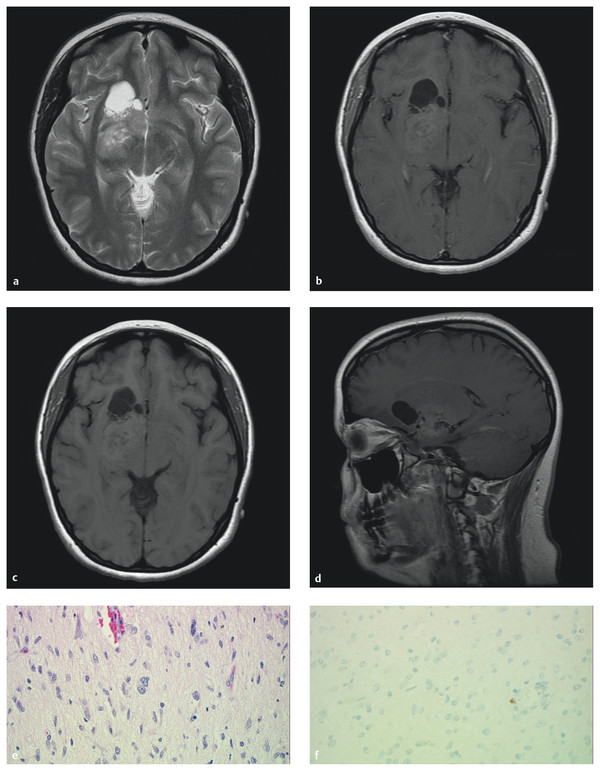

The appearance of gangliogliomas on both CT and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging suggests a benign tumor. They are hypodense to brain on CT and show high signal intensity on T2-weighted or fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images. Enhancement is variable and patchy when present (▶ Fig. 35.2). The lesion will involve the cortex and underlying white matter and will often be adjacent to dysplastic cortex.49 There is often little mass effect or edema. Confirming the relatively indolent and benign nature of the tumor, the inner table of the skull can show some bowing due to the long-term pressure applied by the tumor.17,19

Fig. 35.2 Magnetic resonance imaging of a midline/basal ganglia ganglioglioma in a 17-year-old girl who presented with seizures. (a) Axial T2 image illustrates the typical solid/cystic nature of the tumor and hyperintensity. (b) Axial T1 images with and (c) without contrast demonstrate the enhancement pattern often found in this lesion. (d) The cystic, variably enhancing nature of this difficult tumor is demonstrated again in the sagittal plane with contrast. (e) Hematoxylin and eosin stain (x40) shows disorganized, pleomorphic neurons with binucleation and eosinophilic granular bodies and (f) virtually no cellular proliferation (Ki-67 stain).

DIG is a tumor of infants that is often massive and located in the frontoparietal areas. The vast majority of the mass effect is the result of intratumoral cysts. On MR imaging, there is typically a solid superficial mass or plaque that is avidly enhancing, with septa originating from the solid tumor. Large portions of the tumor enhance after gadolinium administration, including the solid superficial mass, the walls of the intratumoral cysts, and the multiple septa.50,51

Gangliogliomas are more commonly seen in children; however, they can present later in adulthood. Patients generally present with seizures, although the mass effect rarely causes symptoms. Epilepsy resulting from these lesions is often resistant to medications.33 Complete resection should be the goal as it results in the best outcomes for seizure and tumor recurrence, but it may not be possible because of tumor adherence to critical neurovascular structures. Fortunately, patients who undergo subtotal resection can also see improvement in their seizures.49,52 Patients with multiple types of seizures or an extended history of seizures are best managed by a multidisciplinary epilepsy service as lesionectomy alone may not be sufficient for seizure control. These patients may require a more extensive imaging work-up, video electroencephalography (EEG) recording from surface or subdural electrodes, or intraoperative electrocorticography (ECoG).

35.2.2 Treatment and Outcome—Tumor Control

In patients whose tumors are amenable to total resection, no further therapy is required, and the risk for tumor recurrence is quite low. Gangliogliomas—including the desmoplastic variant—are generally benign tumors that are essentially cured by total resection.40,46,49,52–55 This optimistic view is tempered by the fact that those tumors arising from or extending into midline structures are difficult to resect and are often of a higher grade.40,42,56 These children have a higher risk for recurrence, even with radiation therapy. Some authors feel that midline tumors are different pathologically from gangliogliomas that arise in the hemisphere, and that adjunctive therapy, usually radiation, should be administered.34,40,42,56–58 However, the numbers involved are small, and at this time, close neuroimaging follow-up is considered acceptable until progression occurs. Pathologic grade and totality of resection are the best prognosticators for tumor control. In a combined series of over 150 pediatric patients with all grades of ganglioglioma, 94% of the patients remained alive at the most recent follow-up, 95% of patients who presented with seizures remained alive, and all patients with intractable seizures remained alive.34,57–60 Of patients with midline tumors, 76% remained alive. Ninety-seven percent of patients who had a gross total resection (GTR) remained alive, versus 80% who had a subtotal resection (STR).56 Another study, of 42 patients, reported a 56% survival with high-grade tumors and 90% survival with low-grade tumors.61 Luyken et al reported local control to be significantly improved by a temporal lobe location, lower grade, and GTR.41 Karremann et al specifically looked at children with anaplastic histology and found an 88% estimated 5-year survival and GTR to be the best predictors of survival.62

A more recent meta-analysis regarding the role of RT, which included many of the above patients, divided patients into four groups: GTR, GTR + RT, STR, and STR + RT.54 Children were combined with adults for a sample size of 402 patients (232 patients [58%] ages 0 to 19 years). They calculated 10-year local control and OS for each group: rates of local control were 89%, 90%, 52%, and 65%, respectively, and rates of OS were 95%, 95%, 62%, and 74%, respectively. When high-grade tumors were considered, only local control was significantly improved by adding adjuvant RT to STR. They concluded that there was no role for RT when GTR is achieved, and that RT improved local control of both high- and low-grade incompletely resected tumors and therefore should be considered. Liauw et al had similar findings in their study and noted that salvage RT may be less effective than up-front adjuvant therapy.55

DIGs are generally benign and amenable to complete surgical resection; when that can be accomplished, no further therapy is warranted. If an STR is achieved or the tumor recurs, then either observation or re-resection is the appropriate course, respectively.50,51 Residual disease usually does not grow and can even spontaneously disappear.63 Malignant transformation has been reported necessitating chemotherapy.64,65 Radiation is typically not an option, given the very young age of the patients and the large treatment volume that would be required.

35.2.3 Treatment and Outcome—Seizure Control

Gangliogliomas are the most frequent cause of tumor-associated drug-resistant epilepsy in children.33 Both the ganglioglioma itself and the often-associated surrounding cortical dysplasia—present in up to 80%—have been proved to be seizure generators.66–69 Patients whose epilepsy is not controlled with medications are excellent candidates for resective surgery. However, the question of whether lesionectomy alone can be performed or whether lesionectomy plus resection of surrounding tissue, including dysplastic cortex, is necessary to achieve optimal seizure control is unresolved. Some authors consider lesionectomy alone to be sufficient,36,38,49,52,70,71 whereas other authors suggest, when possible, resecting a margin of tissue around the ganglioglioma.35,41,57,67,72–74

Giulioni et al performed lesionectomy alone on a mixed group of 15 glioneuronal tumors (73% gangliogliomas) and reported an 87% rate of seizure freedom (Engel class I).49 They did not note an association with the type or duration of epilepsy, seizure frequency, or completeness of resection. Ogiwara et al took a similar approach in their group of 30 children with gangliogliomas.52 However, they used intraoperative ECoG in 21 patients and resected additional tissue if there was abnormal spike activity. When this was done, 11 of 21 patients had additional surrounding tissue removed. Ninety percent of their patients were seizure-free (Engel class I), and they noted no difference between the rates of seizure freedom in those who had ECoG and those who did not. Of note is that two of their three patients who continued to have seizures had lesionectomy alone performed on extratemporal tumors. Patients with extratemporal tumors treated with lesionectomy alone had 82% seizure freedom. In conclusion, regardless of the approach, most patients experience excellent outcomes with regard to their seizures. The use of ECoG and the extent of resection of tumor and surrounding tissue are decisions best made on a case-by-case basis.

35.3 Dysembryoplastic Neuroepithelial Tumors

DNETs were originally described by Daumas-Duport et al in 1988 and are almost universally associated with seizures.75 Grossly, they have the appearance of an expanded cortex or a megagyrus; histologically, they show disorganized glial and neuronal elements that are characteristically arranged in a columnar appearance oriented perpendicular to the cortical surface. Cytologic atypia of neurons, a feature typical of gangliogliomas, is absent in DNETs. Foci of cortical dysplasia are found in 50 to 90% of cases.60,75–77 DNETs have a predilection for the frontal and temporal lobes and can also be multifocal, but the most common location is the temporal lobe. The presence of cortical dysplasia, young age at the onset of symptoms, and deformity of the overlying calvaria (in up to 60% of cases) suggest that this tumor has a dysembryoplastic origin. Daumas-Duport hypothesized that DNETs arise from the fetal subpial granular layer, an embryologic structure that involutes during the course of normal development.78 It is currently accepted that surgery is the only required therapy, even if residual lesion is present or multiple resections are required.76,78–80

35.3.1 Imaging and Preoperative Evaluation

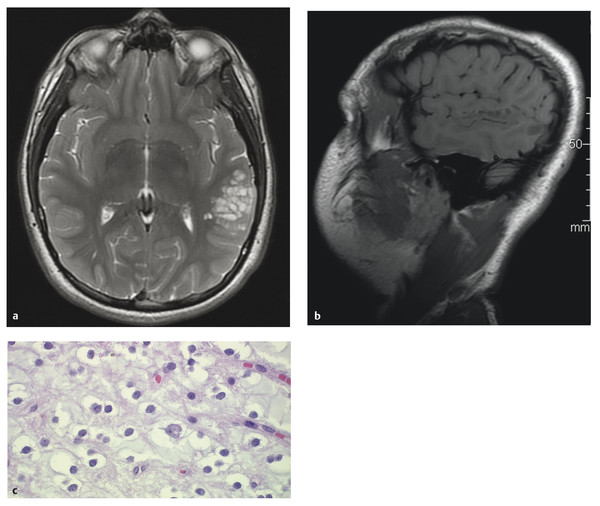

DNETs characteristically appear as well-demarcated, hypodense, and nonenhancing lesions best seen on FLAIR or T2 sequences without peritumoral edema or mass effect (▶ Fig. 35.3).17,79,81 CT will demonstrate calcifications in about a quarter of all cases, and bony remodeling is common.75 Almost all patients present with partial complex seizures, and as in patients with gangliogliomas, the seizures are often disabling because of their frequency, potential for secondary generalization, and poor responsiveness to pharmacotherapy.

Fig. 35.3 This 13-year-old boy presented with seizures and a dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor (DNET). (a) Axial T2 and (b) sagittal noncontrast T1 magnetic resonance images show the typical appearance of a “bubbly” expanded gyrus that is hyperintense on T2 and hypointense on T1. The lesion does not enhance. (c) “Floating neurons”—cortical ganglion cells sitting in small pools of mucin separated by cortical neuropil—are a common but nonspecific feature of DNETs (hematoxylin and eosin stain, x60).

35.3.2 Treatment and Outcome

The indications for surgery are either to obtain tissue for diagnosis or to control seizures. Most series of DNETs have been reported in terms of seizure outcomes. Engel class I outcomes are reported for 50 to 100% of patients.72,75,82,83–93 Some of these studies include several types of tumors and a mixture of pediatric and adult patients. For example, Chang et al reported a large series of 50 adult and pediatric DNETs with a mean follow-up of 5.6 years.83 Over half of the cases were adjacent to areas of cortical dysplasia. Eighty-six percent of patients were seizure-free at 1 year (Engel I). Engel class I patients represented 80% of the group followed out to 10 years. Class I outcome was associated on multivariate analysis with complete resection and extratemporal location. For cases in which ECoG was used, the presence of extralesional spikes (and resection of that cortex) predicted better seizure control. This same group performed a meta-analysis of all reports of DNET and gangliogliomas in adults and children and found that, overall, 80% of patients were seizure-free after resection.94 Short duration of epilepsy (less than 1 year), GTR, and focal seizure type predicted seizure freedom. Pathology (DNET vs. ganglioglioma), lesion location, age, and the use of ECoG were not predictive of seizure freedom. With respect to tumor control, residual tumor may remain dormant for many years, but there are reports of growth of histologically confirmed DNETs on neuroimaging that necessitated reoperation.75,95

35.4 Choroid Plexus Papillomas/Carcinomas

CPPs and CPCs account for 2 to 6% of pediatric brain tumors and 10 to 20% of tumors in children younger than 1 year.96,97 The WHO classifies them as grade I (CPP), grade II (atypical CPP), and grade III (CPC).98 Papillomas show a histologic architecture similar to that of normal choroid plexus; numerous papillae are covered with a simple columnar or cuboidal epithelium. Carcinomas exhibit brain invasion, nuclear atypia, an increased nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, prominent and numerous mitotic figures, and a loss of the normal papillary architecture. The majority of tumors present with signs and symptoms of hydrocephalus because of their characteristically intraventricular location (most commonly in the atrium of the lateral ventricle) and propensity to overproduce CSF. They rarely present in brain parenchyma or the cerebellopontine angle.99 Up to 30% of patients with CPCs have metastatic disease at presentation, necessitating spinal screening for all patients.

35.4.1 Imaging and Preoperative Evaluation

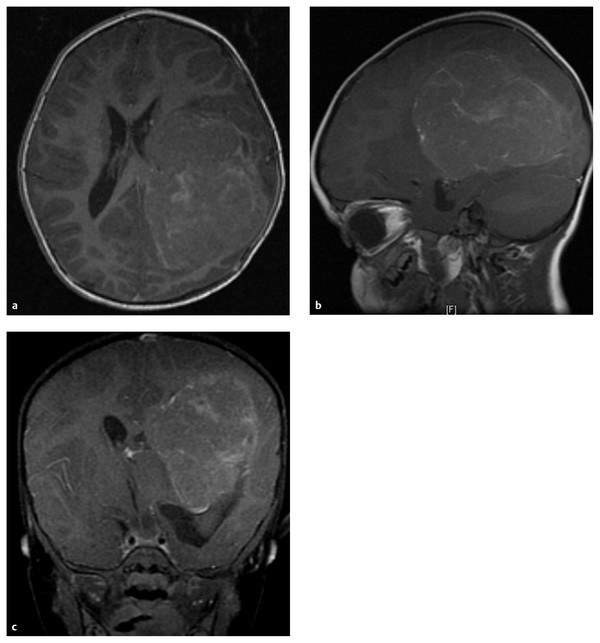

Choroid plexus tumors are isodense to hyperdense to brain on CT and on MR imaging. They have a lobular, cauliflower-like appearance, can be quite large, are hypervascular, and generally enhance avidly with contrast. Hydrocephalus is present in 80% of patients with CPPs. Younger patients are more likely to have supratentorial tumors, whereas patients older than 14 years have a predominance of infratentorial tumors.99 The presence of heterogeneity and surrounding edema of the brain raise the possibility that a lesion is a CPC (▶ Fig. 35.4).100

Fig. 35.4 Axial (a), sagittal (b), and coronal (c) gadolinium-enhanced T1 magnetic resonance images of a 4-year-old girl who presented with progressive hemiparesis. This choroid plexus carcinoma (CPC) was resected. The tumor is located within the ventricle, centered in the atrium, and has a variable enhancement pattern that is often suggestive of a CPC.

35.4.2 Treatment and Outcome

Surgery is the primary treatment for choroid plexus tumors, but this can be challenging because of the hypervascular nature of the tumors coupled with the fact that they are usually found in young children who cannot tolerate excessive blood loss.101–105 This has led to preoperative measures to reduce the tumor’s blood supply. Atrial tumors typically have a dual supply from the posterior lateral and anterior choroidal arteries. Third ventricular tumors are supplied by the posterior medial choroidal artery. These arteries may be embolized immediately before surgery, or neoadjuvant chemotherapy, such as ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide, may be administered—more commonly with CPCs—to devascularize the tumor.106–108 The neurosurgeon can tailor the surgical approach to coagulate the blood supply early, before resecting the tumor. If these feeding vessels are not accessible early in the case, then rapid tumor debulking is performed with the expectation that large volumes of blood products may need to be infused and the resection may require a “staged” approach. CPCs are more difficult to resect because they are friable, and a well-developed plane is lacking between the tumor and brain.

If a CPP is totally resected, then no further therapy is indicated.109 The 5-year survival rate is close to or at 100% in many published series.110 A patient with a CPC who undergoes GTR, rather than STR, has a better chance at long-term survival, but even with GTR, the 5-year survival rate ranges from 30 to 50%. Most authors agree that a completely resected CPC requires adjuvant chemotherapy. For example, a meta-analysis by Wrede et al found that postoperative chemotherapy resulted in a survival benefit, both with RT and without.111 For the subgroup of patients with STRs, 2-year overall survival was better with chemotherapy than without (55% vs. 25%). The addition of RT predicted better survival (47.4% vs. 25.2%). Most authors suggest postoperative chemotherapy for younger patients (i.e., younger than 3 years) and combination chemotherapy and RT for older patients (i.e., older than 3 years).111–115

CPC is often associated with Li-Fraumeni syndrome, in which patients have a germline mutation of TP53, a tumor suppressor gene located on the short arm of chromosome 17.116 This mutation is thought to confer resistance to both RT and chemotherapy.117 Some authors suggest Li-Fraumeni screening of all patients with CPCs.109,118 Patients with CPCs without germline TP53 mutations had a 5-year survival of 82%, compared with 0% if they harbored a mutation.

35.5 Meningiomas

Meningiomas are rare in children, accounting for 1 to 2% of all meningiomas and 0.7 to 4.2% of pediatric brain tumors, but they are becoming more common with an increasing population of long-term survivors of brain tumors who have received cranial irradiation.119–126 The presentation may include elevated intracranial pressure, the new onset of seizures, and focal neurologic deficit. Pediatric meningiomas are strongly associated with neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF-2) and to a lesser degree neufibromatosis type 1 (NF-1).127 Unlike meningiomas in adults, childhood meningiomas are more commonly seen in the posterior fossa, along the orbital nerve, in the ventricles, and without dural attachment in the brain parenchyma or within the sylvian fissure.128 The WHO classifies meningiomas as grade I (typical), II (atypical), and III (anaplastic).119,120

35.5.1 Imaging and Preoperative Evaluation

Pediatric meningiomas are similar to adult tumors with the exception that necrosis and cyst formation are more common in children. They are isodense to hyperdense to brain on CT, with calcification often present. MR imaging often shows an isodense mass that avidly enhances and generally has a dural attachment (▶ Fig. 35.5). Hyperostosis is present in approximately 50% of children with these tumors. Infantile meningiomas can be very large and are often associated with very large intratumoral cysts.17,129 As in choroid plexus tumors, preoperative angiography with embolization may be helpful in detailing the vascular anatomy and decreasing the blood supply in preparation for surgical resection. Conventional angiography or MR venography is also helpful in evaluating sinovenous patency for tumors that involve these structures.

Fig. 35.5 (a) Axial, (b) sagittal, and (c) coronal gadolinium-enhanced T1 magnetic resonance images of a 22-month-old boy who presented with progressive hemiparesis. This large meningioma was resected. Imaging is similar to that of adult meningiomas. The tumor originated from the dura overlying the clinoid and sphenoid wing. (d) Meningotheliomatous-type meningioma (hematoxylin and eosin stain, x20) is characterized by whorls, lobules, indistinct cell borders due to interdigitating cell membranes, and intranuclear pseudo-inclusions (pale areas of the nucleus due to cytoplasmic invaginations). There is a mitotic figure in the middle of the picture.