Chapter 29 Surgery of Extramedullary Tumors

INTRODUCTION

Some authors have suggested the classification of the spinal cord tumor based on the foraminal extension.1

SCHWANNOMA WITH FORAMINAL EXTENSION (CAUDA EQUINA LEVEL)

Although most tumors of the thoracic and lumbar spine are readily accessible via standard spinal exposures, there is a group of tumors that cannot be removed with a simple posterior approach. They are large dumbbell tumors with significant intraspinal and paraspinal involvement (Fig. 29-1), paraspinal tumors located in the upper thoracic region (T1–3) or imbedded within the psoas muscle adjacent to the lumbar spine, and extensive unilateral anterior and posterior paraspinal tumors with significant spinal canal and vertebral column involvement.2 Posterior midline approaches provide bilateral exposure of the entire posterior elements (lamina and facets, the dorsal epidural space, the entire intradural space, and the posterior paraspinal region) and lateral spinal elements (pedicle and lateral epidural space); however, access to the anterior element is limited. For tumors with a large extraforaminal portion, the posterolateral (e.g., lateral extracavitary approach) route should be added.

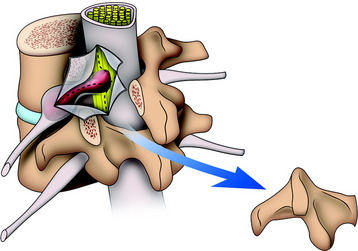

At the cauda equina level, the posterior element is totally removed for exposure of the dural sac and foraminal nerve root. Disarticulation is performed above and below the facet joint. The unilateral complex of superior articular process, transverse process, and inferior articular process is removed from the vertebral body at the point of the pedicle. A part of the spinal canal and unilateral foramen is opened. An underlying mass is seen to originate from the nerve root. The tumor mass–laden nerve root is dissected from the underlying vertebral body. A cottonoid is put under the nerve root. A dural incision is made on the lateral margin of the spinal cord and extended over the tumor mass (Fig. 29-2). The intradural mass is dissected from the surrounding cauda equina, and the origin nerve is cut at the surface of the tumor mass. The distal end of the tumor mass is cut intracapsularly or extracapsularly.

Case I

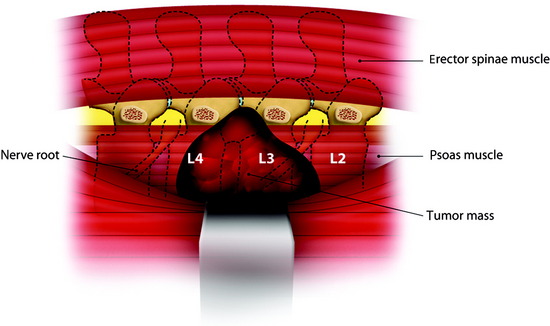

Large Paraspinal Tumor at L3 Level

A patient presents with a schwannoma originating from the L3 nerve root that formed a large extraforaminal paraspinal mass at the paraspinal area (Fig. 29-3). The extraforaminal mass has enlarged to expand the left psoas muscle (Fig. 29-4). For the removal of the large extraforaminal portion, extensive paraspinal exposure is required. The lateral extracavitary approach is useful in this situation. This single-staged approach provides excellent exposure of intradural structures as well as extensive access to the anterior and posterior paraspinal region, ventral spinal canal, and vertebral body (Fig. 29-5).

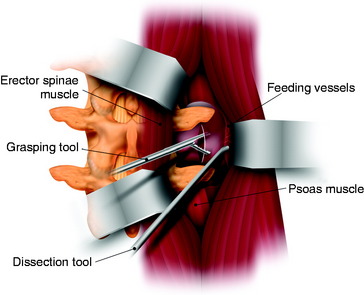

For one-stage removal of the tumor mass, the approach should be performed from both the midline and paramedian route. A hockey-stick incision with the midline long limb centered over the abnormality and the short limb gently curving 8–10 cm toward the tumor side is made. With the midline approach, the intraspinal mass is removed. Once the midline soft tissue dissection is complete, the lateral limb of the skin incision is opened. The thoracodorsal fascia is incised. The lateral margin of the paraspinal muscle is identified and medially elevated to expose the quadratus lumborum and psoas muscles. Detachment of the lateral margin of the paraspinal muscle insertion from the iliac crest and resection of a posterosuperior iliac crest segment facilitate ventral exposure at lower lumbar (i.e., below L4) levels. The paraspinal muscle dissection continues over the facet joints to join the midline dissection. This allows the surgeon to simultaneously or alternatively work on either side of the now completely mobilized paraspinal muscle mass. The L3 and L4 transverse process should be resected to expose the cephalocaudal extent of the tumor mass. The intertransverse ligament and psoas muscle are released from the transverse process to the lateral pedicle margin, at which time the posterior tumor capsule is seen. After the tumor capsule incision is complete, internal debulking is attempted. After the interior of the tumor mass is decompressed, the capsule shrinks. As the tumor capsule is tractioned, the interface between the tumor capsule and psoas muscle is dissected (Fig. 29-6). During dissection, feeding vessels are encountered and should be ligated and cut down. Internal debulking and capsule dissection are repeated. The L2 and L4 nerve roots can hinder ventral exposure because they cross the surgical field and, unlike thoracic nerves, cannot be sacrificed and dorsally displaced. Dissection of lumbar nerves over several centimeters allows for adequate nerve mobilization and prevents a postoperative stretch palsy. Proximal dissection of the segmental nerves identifies the foramen. Vessel loop retraction of these nerves may improve ventral visualization. Depression of the psoas muscle after lumbar nerve dissection provides anterior lumbar paraspinal exposure. Most paraspinal or dumbbell tumors are closely applied to the spine. The psoas muscle is bluntly dissected ventrally off the lateral vertebral body with Cobb elevators. Sharp dissection may be required at the disc space. Dorsal segmental and foraminal branches from the lumbar vessels are cauterized and divided. The margins of the pedicle are sharply defined with curettes. Posterior element (facet joint, pedicle, and transverse process) removal exposes the lateral dural margin, which facilitates dissection and improves ventral canal visualization. Mobilization of the segmental nerves continues to the lateral dural margin. If a two-stage operation is planned, the extraforaminal paraspinal mass is removed with a retroperitoneal anterolateral approach.

Advantages of the Lateral Extracavitary Approach in Spinal Cord Tumor Surgery

Case II

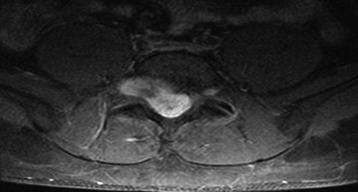

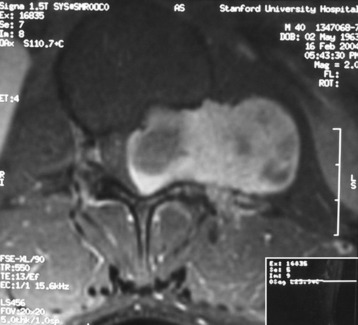

On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), a well-enhancing intraspinal and extraspinal mass was detected at the L1 level (Figs. 29-7 and 29-8). The operation was performed with a pure posterior approach. The overall appearance of the tumor mass after removal of the laminofacetal complex is shown in Figure 29-9. The intradural mass was removed first, and the foraminal mass was removed later. The intradural portion of the tumor can be safely removed with standard microsurgical techniques via laminectomy with direct visualization of the tumor-spinal cord interface and secure identification of the nerve root attachment. A unilateral facetectomy and a T-shaped lateral dural incision over the root sleeve provide contiguous exposure of the foraminal portion of the tumor. The origin rootlet (dorsal root) was cut and the ventral root was saved (Fig. 29-10). Although the motor root can be preserved with intradural dorsal nerve sheath tumors, sacrifice of the entire spinal nerve is usually required once the tumor extends distal to the dorsal root ganglia. Even though the entire spinal nerve is transected, significant motor deficit is rare.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree