27 Surgical Treatment Modalities for Cervical Stenosis: Central Cord Syndrome and Other Spinal Cord Injuries in the Elderly

KEY POINTS

Introduction

Patients presenting following cervical spinal cord injuries with disproportionate weakness of the hands and arms and relative preservation of lower extremity strength are often categorized as having either a cruciate paralysis or, more commonly, acute central cervical spinal cord injury (Box 27-1).

Acute central cord syndrome was first described in 1954 by Schneider, in a case series of 8 patients with neurological deficits following hyperextension injury to the cervical spine and a review of another 6 cases reported in the literature with a similar injury mechanism and neurological presentation. 1

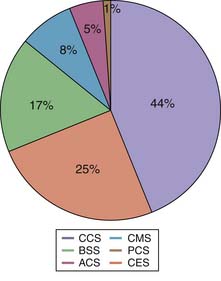

It is estimated that the annual incidence of SCI varies between 11.5 to 53.4 per million population.2 In the United States, the annual incidence is around 40 per million. Central cord syndrome is the most common spinal cord injury pattern.3 The relative distribution of other types of SCI is shown in Figure 27-1.

Mechanism

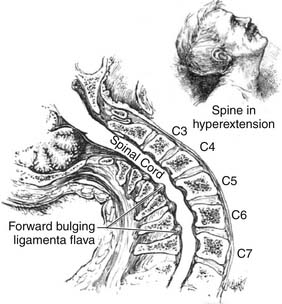

Based on radiographic, operative, and postmortem findings, Schneider postulated that during forceful hyperextension the anterior osteophytes and the bulging of the ligamentum flavum caused significant anteroposterior narrowing of the spinal canal and contusion of the spinal cord (Figure 27-2). He noted in the postmortem findings that the maximum injury was in the central part of the spinal cord. The mechanism of central cord syndrome is a hyperextension injury, often on a background of long-standing cervical spondylosis, with no bony or ligamentous injury. Hyperextension of the cervical spine causes overlapping of the laminae and buckling of the ligamentum flavum, reducing the canal diameter by a further 2 to 3 mm. This compromise may cause significant acute cord compression in an aging spondylotic cervical spine with preexisting discoligamentous and osseous compression. It is estimated that this mechanism of hyperextension accounts for around 50% of cases of acute traumatic central cord syndrome (ATCCS). The other mechanisms are fractures and/or subluxations and herniated nucleus pulposus.4 The most common mechanism of injury in the elderly population is a low-energy ground-level fall with impact on the head or chin causing forceful hyperextension of the neck. Typically this low-energy impact does not cause any bony injury.

Figure 27-2 Original drawing of the hyperextension mechanism from Schneider’s paper in 1954.

(From Schneider RC, Cherry G, Pantek H: The syndrome of acute central cervical spinal cord injury; with special reference to the mechanisms involved in hyperextension injuries of cervical spine [part 1], J Neurosurg 11:546-577, 1954.)

Definition of Central Cord Syndrome

Central cord syndrome was described by Schneider in 1954: ‘‘It is characterized by disproportionately more motor impairment of the upper than the lower extremities, bladder dysfunction, usually urinary retention, and varying degrees of sensory loss below the level of the lesion.’’ (Box 27-2).1

Incidence and Age

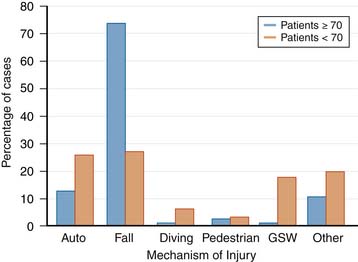

The average age of spinal cord injury (SCI) has increased from 28.7 to 38 years, and the percentage of spinal cord injury in people over 60 years of age has increased from 4.7% to 11.5%. After the age of 45 years, falls are the most common cause of cervical spinal cord injury, increasing in incidence with advancing age. In one series, 74% of injuries in patients 70 years of age or older were caused by falls (Figure 27-3).5 SCI in the elderly typically results from a low-energy injury sustained from a fall at ground level. There is a bimodal pattern of the age distribution in ATCCS patients. The increase in age has had an impact on the pathogenesis, functional deficit, recovery, and rehabilitation of patients with spinal cord injuries.6 In general, older patients demonstrate less recovery from spinal cord injury compared to younger patients (Box 27-3).7 Experimental animal studies have shown that increased age increases the area of pathology and amount of demyelination, while demonstrating a significantly lower amount of endogenous remyelination following induced SCI.6 These studies have demonstrated that abnormalities in myelination and functional deficits secondary to SCI are age-related.

Advances in medicine seen over the past five decades have resulted in a dramatic increase in life expectancy following spinal cord injury. At present, the available data would suggest the mortality among spinal cord injury patients is around 3.8% in the first year post-injury, 1.6% in the second year post-injury, and approximately 1.2% a year over the next 10 years.8 The chronological age, degree of injury severity, injury completeness, and neurological level are the most important predictors of mortality. The annual mortality rate varies between 0.4% and 0.5%.

Basic Science

Pathophysiology of Acute Traumatic Central Cord Syndrome (ATCCS)

The peripheral compressive forces exerted on the spinal cord cause concussion, and contusion of the spinal cord results in a primary and secondary neuronal injury following the acute trauma. MRI and histopathological studies have shown that ATCCS is predominantly a white matter injury. Intramedullary hemorrhage, as was previously thought in the original descriptions, is not a necessary feature of the syndrome. However, rarely and in more severe trauma, bleeding into the central part of the cord may cause ATCCS, portending a less favorable prognosis. These histological changes reflect stasis of axoplasmic flow and both intracellular and extracellular edematous injury. The secondary injury is facilitated by a cascade of events mediated by systemic and local vascular insults, electrolyte shifts, edema, and excitotoxicity. The pathophysiological changes can progress in the first few days after the injury, both proximally and distally.9

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree