Figure 38.1. Plain radiograph showing cervical spine fracture and dislocation of C5-C6 with bilateral locking of facets.

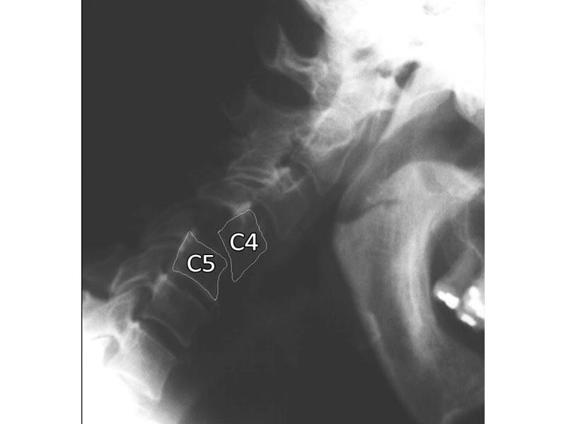

Figure 38.2. Dynamic radiograph showing cervical spine in flexion with subluxation of C4-C5.

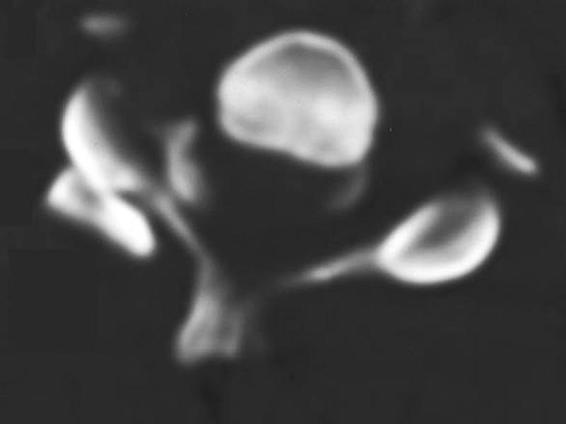

Figure 38.3. Axial tomography of the spinal column showing unilateral facet lock on the left.

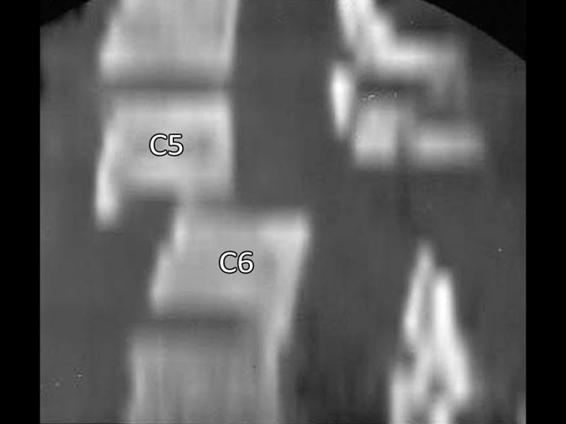

Figure 38.4. Computed tomography sagittal reconstruction of a spinal column fracture with dislocation of C5-C6, canal stenosis and rupture of the posterior ligaments.

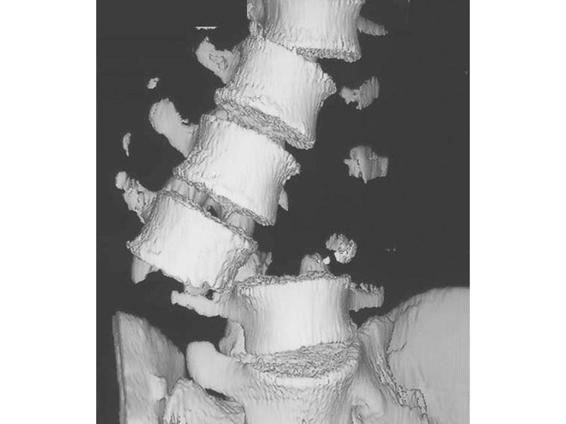

Figure 38.5. Computed tomography 3D reconstruction of the spinal column with a fracture and loss of articular segment L2-L4.

38.9 Surgical Treatment

The aim of surgical treatment of spine fractures is to decompress the spinal cord and protect it, restore stability, and promote neurological recovery. In many cases, however, stability can be achieved with the use of external orthoses (vests, halo traction, etc.).

Some types of fractures are inherently unstable and require surgery with internal fixation. In such circumstances, opinions differ about what should be done (anterior, posterior, type of instrumentation) and when it should be done (immediate surgery, early or late).

The only universally accepted indication for immediate surgery is progressive neurological deterioration in a patient with spinal canal stenosis due to bone fragments, disc, or hematoma, or an irreducible dislocation. Also, spinal cord compression in a patient with incomplete neurological injury is allowed in some centres as a criterion for immediate decompression.

Figure 38.6. MRI of the cervical spine (T2). Postoperative C5 corpectomy. Note the signal change in the vertebral bodies corresponding to the implant material (screws and plate) and the signal change in the spinal injury showing hemorrhagic contusion and perilesional edema.

There are several published studies showing increased morbidity and neurological deterioration after early surgery for traumatic SCI. In contrast, more recently, several authors recommended early surgical intervention, especially in the anterior cervical spine, to allow early mobilization of the patient and reduce complications. In fact, the SCI patient is susceptible to various systemic and neurological complications despite treatment, including pneumonia, decubitus ulcer, thrombophlebitis and pulmonary embolism. It seems obvious that keeping the patient immobilized in bed will not help to avoid this type of complication. Wilberger in 1991 showed a significant reduction (by half) of such complications with early surgery without increasing neurological morbidity. One can also argue that decompression of the spinal cord in the acute phase, by reducing the degree of ischemia, can reduce the effect of the secondary pathophysiological cascade that occurs after trauma. In a recent study, a reanalysis of NASCAR II, there was no statistically significant benefit from early or late surgery in relation to the degree of recovery. There was a trend toward better recovery in patients operated on in the first 25 hours or after 100 hours as compared to the intermediate surgery group.

Currently, it is accepted that if surgery is needed for the treatment of a broken column, assuming that the patient is clinically stable, there is no significant increase in risk associated with early intervention and reduction of downtime can be considerably conducive to patient recovery.

38.10 Functional Independence Measure (FIM)

To fully describe the impact of SCI on the individual and to monitor and evaluate the progress associated with treatment, assessment of activities of daily living is performed. The Functional Independence Measure (FIM) is a tool to assess the degree of function; it is widely used in the United States and is gaining acceptance internationally.

FIM focuses on six areas of functioning: self-care, sphincter control, mobility, locomotion, communication and psychosocial interaction. For each area two or more activities/elements are evaluated for a total of 18 items. For example, self-care is composed of six activities: eating, grooming, bathing, dressing the upper body, dressing the lower body, and personal hygiene (Figure 38.7).

Each of the 18 items is evaluated in terms of independence of function on a 7-point scale (Table 38.5).

- 7: Complete Independence. Fully independent.

- 6: Modified Independence. Requiring the use of a device but no physical help.

- 5: Supervision. Requiring only standby assistance or verbal prompting or help with set-up.

- 4: Minimal Assistance. Requiring incidental hands-on help only (subject performs >75% of the task.

- 3: Moderate Assistance. Subject still performs 50-75% of the task.

- 2: Maximal Assistance. Subject provides less than half of the effort (25 to 50%).

- 1: Total Assistance. Subject contributes <25% of the effort or is unable to do the task.

Points | Item | Assistance |

7 | Total independence (timely, safely) | Not needed |

6 | Modified independence (extra time, devices) | |

Modified dependence | Needed | |

5 | Supervision (coaxing, cuing, prompting) | |

4 | Minimal assistance (performs 75% or more of task) | |

3 | Moderate assistance (performs 50-74% of task) | |

Complete dependence | ||

2 | Maximal assistance (performs 25-49% of task) | |

1 | Total assistance (performs <25% of task) |

Table 38.5. The Functional Independence Measure (FIM) scale.

Figure 38.7. FIM form.

Thus, the total FIM score (the sum of all activities) estimates the degree of disability in terms of safety, dependency on others and devices needed. The profile of scores by area are specific aspects of daily life that are most affected by SCI.

When assessing SCI patients with the FIM, it should be taken into account that the tool was originally developed for evaluating the disabled in general and that it covers broad areas of activities affected by disability. Although we have explored the reliability and validity of the FIM, its validity as an instrument to accurately measure the degree of function across the population with SCI has yet to be demonstrated empirically. For example, it is unclear whether the self-care items are sufficiently sensitive to assess changes in function observed during the rehabilitation of quadriplegics. In addition, we found the items investigating areas of communication and social life less reliable than other areas of evaluation.

Despite these difficulties, we recommend the use of FIM as it is relatively easy to use, reflects major functional aspects in SCI, and the parameters for its use were carefully constructed.

Personal care | Admission | Release | Date |

A. Eating | |||

B. Grooming | |||

C. Bathing | |||

D. Dressing upper body | |||

E. Dressing lower body | |||

F. Toileting | |||

Sphincter control | |||

G. Bladder control | |||

H. Bowel management | |||

Mobility transfer | |||

I. Bed, chair, wheelchair | |||

J. Toilet | |||

K. Tub or shower | |||

Locomotion | |||

L. Walking, wheelchair | |||

M. Stairs | |||

Communication | |||

N. Comprehension (audio/visual) | |||

O. Expression – verbal, non-verbal | |||

Psychosocial adjustment and cognition | |||

P. Social interaction | |||

Q. Problem solving | |||

R. Memory | |||

TOTAL | |||

Table 38.6. Functional Independence Measure chart.

General References

1. Albert TJ, Kim DH. Timing of surgical stabilization after cervical and thoracic trauma. J Neurosurg Spine 2005; 3: 182-90

2. Anon. Management of acute spinal cord injuries in an intensive care unit or other monitored setting. Neurosurgery 2002; 50(Suppl): 63-72

3. Benzel EC. Spine Surgery. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2005; pp. 512-71

4. Bracken MB, Shepard MJ, Collins WF, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of methylprednisolone or naloxone in the treatment of acute spinal cord injury: results of the Second National Acute Spinal Cord Injury study. N Engl J Med 1990;322:1405-11

5. DeVivo MJ, Kartus PL, Stover SL, et al. Cause of death For patients with spinal cord injury. Arch Intern Med 1989; 149: 1761-6

6. DeVivo MJ, Krause JS, Lammertse DP. Recent trends in mortality and causes of death among persons with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999; 80: 14111-9

7. Fehlings MF, Perrin RG. The role and timing of early decompression for cervical spinal cord injury: update with a review of recent clinical evidence. Injury 2005; 36: B13-B26

8. Fehlings MG, Baptiste DC. Current status of clinical trials for acute spinal cord injury. Injury 2005; 36: B113-B122

9. Larson SJ, Holst RA, Hemmy DC, et al. lateral extracavitary approach to traumatic lesions of the thoracic-level spinal cord injury. Spine 1993; 45: 628-37

10. Management of acute central spinal cord injuries. Neurosurgery 2002; 50: S166-S172

11. Marshall LF, Knowlton S, Garfin SR, et al. deterioration following spinal cord injury: a multicenter study. J Neurosurg 1987 ;66: 400-4

12. The National SCI Statistical Center. Spinal Cord injury: Facts and Figures at a Glance. University of Alabama at Birmingham National Spinal Cord Injury Center, June 2005

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree