Chapter 24 Spondylolisthesis is the ventral displacement of the proximal spinal column to the distal spinal column. Taillard1,2 describes spondylolisthesis as a “forward slippage of the vertebral body together with its pedicles, transverse processes, and upper articular processes engendered by a break in the continuity or an elongation of the pars interarticularis.” The most common location of spondylolisthesis is the lumbosacral junction, although it may be found anywhere in the spine. The spine that is slipping carries the trunk along with it. Spondylolisthesis is the end result of different pathologic processes. These processes result in similar deformities because of the morphology and biomechanics of the lumbosacral junction. Stability of the lumbosacral junction in the human is dependent on the pelvic incidence (the sum of the sacral slope and the pelvic tilt) and an intact bone, disk ligamentous complex. The pelvic incidence does not change and is the pelvic morphology that will determine stance attitudes of the spine. The spatial orientation of L5 to the sacrum invites shear forces. The shear forces are resisted by the disk and the posterior bony elements. The pars interarticularis is the bony bridge between L5 and the sacrum and is the weak link. Once the tension band or bony hook is lost by either fracture or dysplasia, the anterior column can migrate forward. Every surgeon who sees patients with spondylolisthesis knows that most do not progress, some progress a great deal, some are not painful, some are very painful, and most are not deforming, whereas some are very deforming. Some respond to in situ posterior-lateral fusion whereas some progress and have multiple pseudarthoses. It is most important for the surgeon to carefully analyze each case and gain as much information as possible before proposing a surgical intervention. The condition was first described by Herbiniaux,3 a Belgium obstetrician who found the dislocation impeded a normal delivery. Few topics in spinal pathology have such varied clinical and anatomic aspects as spondylolisthesis. There are few pathologic conditions of the spine for which there are so many controversial procedures. The classification of spondylolisthesis is important to study. It is important to classify and analyze each individual patient’s spondylolisthesis. Newman4 and Wiltse5,6 have their classifications, but we believe the Marchetti-Bartolozzi7 (1994) classification is the best to date (Table 24–1). This classification divides the spondylolisthesis into two groups: developmental and acquired. This is fundamental and will make studying this condition easier to understand. The developmental group is further divided into high and low dysplasia both with lysis or elongation of the pars. The low dysplastic group is not as difficult to treat as the high dysplastic group. The high dysplastic group with L5 rolling forward was once thought of as congenital, but that would be as rare as a teratologic hip dislocation. These slips have the potential to progress to a spondyloptosis if untreated or mismanaged. The presence of an intact neural arch in these high dysplastic cases presents with a high risk of cauda equina syndrome prior to or at the time of surgical intervention. The acquired forms are self-evident and the most common are the athletic, the postsurgical, and the degenerative groups. The degenerate group may be seen with or without a lytic defect of the pars (Fig. 24–1).

Surgical Treatment of Spondylolisthesis

♦ Classification

Developmental | Acquired |

Low dysplasia | Traumatic |

Lysis or elongation | Acute |

High dysplasia | Stress |

Lysis or elongation | Postsurgery |

| Pathologic |

♦ Diagnosis

The diagnosis is usually made on x-ray imaging. Sometimes it will be discovered incidentally on genital-urinary or bowel x-ray films. The fact that someone thought enough of the complaints to warrant an x-ray indicates that the condition is symptomatic at some times.

Many young patients are brought in with x-ray films and say they have no complaints. These patients need close observation and some physical training.

The usual x-ray types are the standard anterior/posterior (AP), lateral (Lat.), both obliques, and spot lateral. Standing lateral is needed, and an MRI is important if an intervention is contemplated. With this information, the surgeon should be able to decide if the spondylolisthesis is developmental or acquired. If the developmental form is diagnosed, the degree of dysplasia is determined. The quality of the pedicles, pars, and inferior facets of L5 are noted. The sacral facets are noted along with the presence of spina bifida. These elements make up the bony hook. The age of the patient is important as progression will be seen in young, high dysplastic patients. The standing lateral x-ray will help determine the degree of lordosis and the gravity line. Pelvic incidence may be measured. The sacrum may be deformed and should be noted. Sometimes the sacrum will appear bent and look like a shrimp.8 The height, hydration, and competency of the disk are ascertained (Fig. 24–2).

It is vital to know all these facts when making a diagnosis and planning treatment. It is not just simply another “isthmic spondylolisthesis.”

♦ Age of Patient

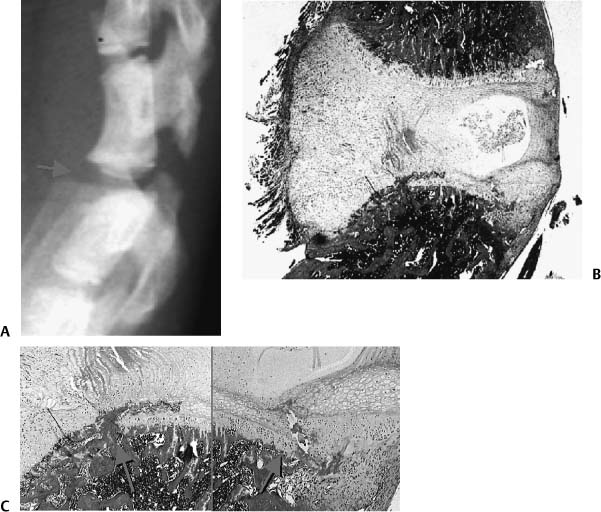

Spondylolisthesis in patients with an open vertebral apophysis occurs through the growth plate. MRIs in children dramatically illustrate this pathology. Research by Sairyo et al. has demonstrated the slip occurring through the growth plate and the subsequent growth changes.9 They created a surgical defect in the pars of young animals and then studied the sacrums after a period of time. They have histological evidence of the slip through the growth plate, causing an alteration of growth.10 To the authors’ minds, this explains the changes seen in the L5 and sacral bodies in young children with spondylolisthesis (Fig. 24–3).

Patients with less dysplasia or with a stronger bone, disk ligamentous complex have more resistance to shear. Less shear force in children means less growth plate slip. Likewise in patients with less lordosis, there will be less shear force. On the other hand, patients with a large lordosis and high dysplasia (poor bony hook) are set up for large slips and/or bony deformity of the sacrum and L5.

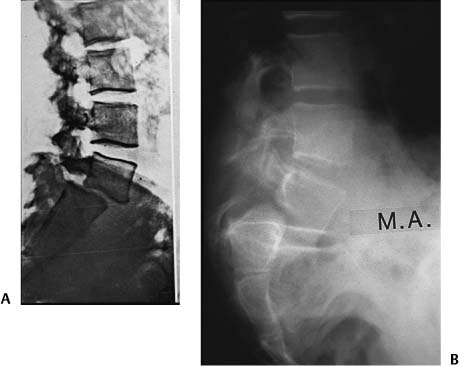

Figure 24–1 These x-ray images illustrate the difference between developmental and acquired spondylolisthesis. The acquired form in (A) has a translational slip and no deformity of the sacrum and/or L5. The developmental form (B) has the forward roll of L5, the deformity of the sacrum, the elongated and separated pars. These cases are very different types of spondylolisthesis. The deformity and the appearance of the sacrum in the developmental type can be explained by the histology of the condition seen in Fig. 24–3. The doming of the sacrum is the result of the epiphysiolysis and the Hueter-Volkman epiphyseal pressure rule.

♦ Etiology

There are many theories of etiology for spondylolisthesis.11–20

The most prevalent one is shear stress across the lumbosacral joint. Upright posture causes shear. Physical activity causes shear. These forces alone may lead to a stress fracture of otherwise healthy pars. The stress is now on the disk or growth plate (depending on age) and a slip may occur.

If the pars is dysplastic and the lordosis severe, slipping will occur.

The common denominator is the verticality of the sacral plateau, quality of the bony hook, and stress. Lordosis is correlated with the sacral slope.

♦ Anatomy

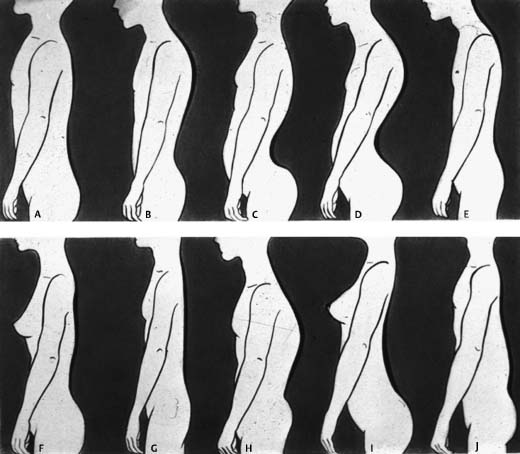

To study anatomy of spondylolisthesis, one must understand several variables. The place to start is stance and the gravity line. A normal spine in stance phase in the coronal plane is straight and in the sagittal plane has several curves. The variety of curves in the sagittal plane has been well described by several authors21–29 and is illustrated by Stagnara’s famous drawing (Fig. 24–4).

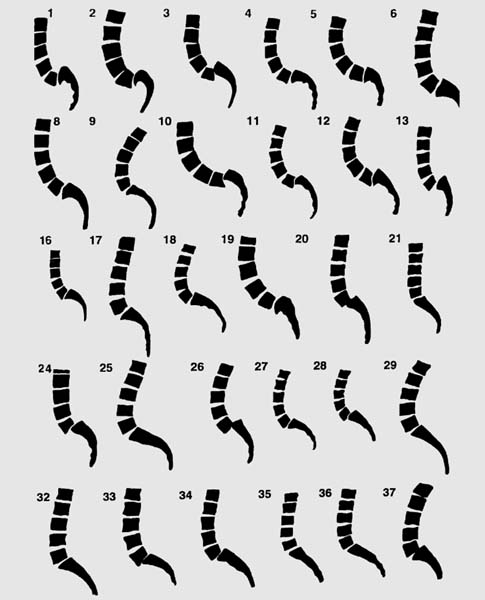

Figure 24–2 These tracings illustrate the variety of sacral shapes seen in spondylolisthesis. The actual final shape of the sacrum and the degree of slip is probably predetermined by the amount of lordosis, the verticality of the sacral slope, and the quality of the posterior tether. The result can be a slip of various degrees, a bent sacrum, or both. All of theses factors are dependent on the morphology of the sacrum. Pelvic incidence is a way to measure the morphology of the pelvis.

Why are there so many normal variations of sagittal configuration of the spine?

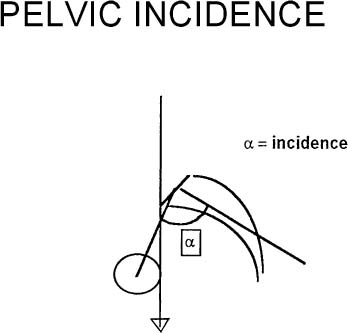

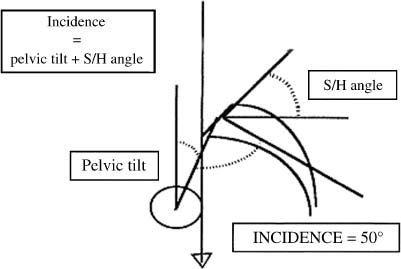

Spinopelvic sagittal balance in normal persons is a combination of spinal and pelvic shape parameters. To best determine pelvic morphology, Legaye et al. and Duval-Beaupere et al.30–34 have described pelvic incidence as a fundamental anatomic parameter that is constant and specific for each individual. It determines pelvic orientation and lumbar lordosis. Pelvic incidence (PI) is the angle between a line perpendicular to the sacral plate and a line joining the sacral plate to the axis of the femoral heads (Fig. 24–5).

The sacral slope (SS) is defined as the angle the sacral plate makes with the horizontal. Pelvic tilt (PT) is defined as the angle of a line from the midpoint of the sacral plate to the vertical. The sum of SS PT PI.

Pelvic incidence is a constant and sacral slope and pelvic tilt are variable. Lordosis is dependent on the sacral slope and also on the dorsal kyphosis. These are also variable parameters. Generally, the spinal shape follows the pelvic shape. The more slope, the more lordosis. The more the pelvic incidence increases, the higher will be the sacral slope and the higher the lumbar lordosis.35,36 However, the lumbar lordosis also must conform with the dorsal kyphosis (Fig. 24–6).

The global gravity line in most normal people lies just anterior to the axis of the femoral heads. The sagittal vertical axis line falls from C7 in front of T7 behind L3 and across S2. This lines helps to ascertain the global balance of the spine, which is variable.

Figure 24–3 (A) Three-week postoperative x-ray image of young rat. (B) Histologic evaluation reveals the nucleus shifted posteriorly and the normal growth layer disturbed anteriorly; (C) reveals magnifcation of the growth plate disturbance.

Figure 24–4 This drawing illustrates the possible sagittal variations. These variations are related to the pelvic incidence, the gravity line, the balance between the dorsal kyphosis and lumbar lordosis, femoral anteversion, and probably the trochanter knee ankle line.

Vertebral growth continues until ages 16 to 18. Longitudinal growth is by enchrondral ossification. Latitudinal growth is through membranous bone formation, modeling, and remodeling, all of which are biomechanical responsive patterns.37

Once we have ascertained the position of the pelvis in space, we can relate the lordosis of the spine to it. Biomechanical studies have continued to show stress concentrations on the pars. It would seem obvious that the more lordotic the spine, the more stress force on the pars.

Figure 24–6 The sacral slope (SS) is defined as the angle the sacral plate makes with the horizontal. Pelvic tilt (PT) is defined as the angle of a line from the midpoint of the sacral plate to the vertical. The sum of SS + PT = PI. Pelvic incidence (PI) is a constant, and sacral slope and pelvic tilt are variable. Lordosis is dependent on the sacral slope and also on the dorsal kyphosis. These are also variable parameters. Generally, the sagittal spinal shape follows the pelvic shape.

The lumbar vertebra 5 has strong attachments to the pelvis through the ilio-lumbar ligaments. When L5 is deep in the pelvis or has sacralization, forces may cause the spondylolisthesis to be at the next cephalad level. When attempting to reduce a spondylolisthesis, releasing the contracted ilio-lumbar ligament will aid reduction by mobilizing the segment.

We do not know if other authors have attempted to grade the amount of dysplasia.

We attempted to grade the dysplasia on a 1 to 4 basis.38 We noted the spina bifida of L5 and sacrum, the quality of the inferior facets of L5, the quality of the sacral facets, the shape of L5 and sacrum, and the elongation or break in the pars. This helped us determine high or low dysplasia.

Another finding not previously studied was the shape of the sacrum. Some sacrums are severely bent, which makes the sacral plateau vertical.8 This makes reduction difficult and will increase the lordosis if attempted. We believe the sacrum bends because of the degree of lordosis, degrees of the sacral slope, and a good bony hook. This situation is dependent on the pelvic incidence. The stress is present, but if the hook is sound, the sacrum deforms through the growth plate and bends.

The degree of slip continues to be measured by the Meyerding method. It is not the best method but seems to be universally accepted. When the sacrum is domed and L5 wedged, it is difficult to have an accurate measurement. Usually in these cases, the spondylolisthesis will be graded lower than it is, and the surgeon may feel there is time to wait, watch, and see.

The spine is very adaptable; many developmental severe spondylolisthesis may adapt and the clinical appearance will be acceptable and the pain level low. Observation may be the best treatment.

♦ Biomechanics

The body’s gravity line falls anterior to the lumbosacral junction. As a result, there is a great shear stress on this joint.39–47

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree