Chapter 115 Tarlov Cysts

Tarlov first described these cysts in 1938 during his autopsy studies of the filum terminale at the Montreal Neurological Institute.1 Since his seminal report, numerous cases of symptomatic Tarlov cysts have been published in the literature.2–7 With the advent of MRI, our ability to diagnose meningeal cysts, such as Tarlov cysts, has been enhanced.

Epidemiology and Histology

Tarlov, or perineurial, cysts are one of the most common forms of meningeal cyst. Estimates of the prevalence of meningeal cysts, including Tarlov cysts, in the general population vary, but generally are in the 5% range.8 In a study of 500 consecutive patients with back pain undergoing lumbosacral MRI, 5% were found to have one or more meningeal cysts. Among this latter group, the cyst was thought to be the source of the symptoms in 1% of the cases. Tarlov cysts, particularly those that are symptomatic, are more common among women. The reason for this is unclear, and we have postulated that there may be gender-related differences in the fundamental make-up of dura mater or spinal nerve roots that produce this epidemiologic disparity.

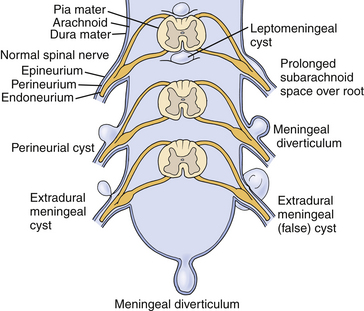

Tarlov distinguished perineurial cysts from other meningeal cysts based on several histologic criteria.1,9,10 He defined them as perineurial dilations that develop between the endoneurium and perineurium, typically of the S2 or 3 nerve roots, just proximal to the junction of the dorsal root ganglion and nerve root (Fig. 115-1). Simply stated, each cyst is a dilated spinal nerve root sheath, and the individual nerve fibers of that root are found running within the cyst cavity or its inner lining. Other meningeal cyst subtypes, such as meningeal diverticula and arachnoid cysts, typically are devoid of nerve root fiber elements.

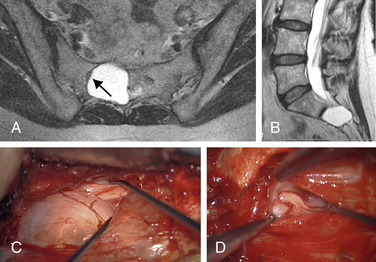

Tarlov cysts can be single or multiple, and can develop anywhere along the spine where nerve roots are present. Progressive cyst enlargement can cause significant bony erosion and impingement of adjacent spinal nerve roots, producing corresponding radiculopathies. For example, a Tarlov cyst in the sacral spinal canal arising from the S3 nerve root can cause symptomatic impingement of the ipsilateral S2 nerve root beside it, and of the S4 or S5 nerve root below (Fig. 115-2). A Tarlov cyst can also produce contralateral symptoms if it is large enough to extend across the midline and compress contralateral nerve roots. Additionally, the nerve root fibers running inside a Tarlov cyst often are attenuated and splayed out over the inner wall of the cyst. This neural fiber alteration and stretching also are suspected of causing symptoms.

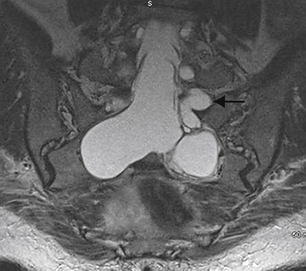

Tarlov cysts occasionally can be found in combination with other meningeal cysts. For example, patients with connective tissue disorders, such as Marfan syndrome, can have Tarlov cysts and large ectatic dural cysts so extensive that the distal spinal sac extends out into the pelvis (Fig. 115-3).

The pathogenesis of Tarlov cysts remains unclear. Tarlov proposed that cyst formation could be the result of trauma, ischemic degeneration, inflammation, or hemorrhagic infiltration from the subarachnoid space.1,9,10 Some patients with symptomatic Tarlov cysts report a history of sacral trauma, and evidence of old hemorrhage in the form of hemosiderin deposits and dystrophic calcification within Tarlov cyst walls supports prior trauma as an etiologic factor.7,11–13 Other reports have suggested that Tarlov cysts result from arachnoidal proliferation or blockage of perineurial fluid flow.14,15 Nabors et al. support a developmental origin, although an association between Tarlov cysts and spinal dysraphism is not as strong as that with other types of meningeal cysts.16 Only two patients with symptomatic Tarlov cysts and spina bifida have been reported, and the relationship could have been coincidental.7,17

Strully et al.18,19 and Smith20 proposed that Tarlov cysts form as a result of increased CSF hydrostatic pressure. They point out that spinal nerve roots are in communication with the thecal sac, and that there is myelographic evidence that spinal fluid flows within the nerve roots and could produce dilatation due to either higher hydrostatic pressure or inherent, traumatic, or iatrogenic weakness in the nerve root sheath. They also point out that the frequency and size of Tarlov cysts along the spine can be correlated with the rostral-caudal hydrostatic pressure gradient.17,18 Several reports on patients with Tarlov cysts have documented either a history of straining or coughing or an exacerbation of symptoms by these maneuvers.7,10,11,18 We also are aware of two cases of Tarlov cysts in patients with pseudotumor cerebri. However, no criteria have been established to determine who might benefit from CSF shunting for Tarlov cysts, and investigations are ongoing.

Diagnosis

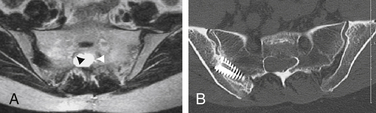

Even more unfortunately, we have encountered patients with symptomatic Tarlov cysts that were misdiagnosed with a variety of other ailments and treated unsuccessfully with a variety of procedures, such as hysterectomy, laparoscopic exploration, endometriosis surgery, oophorectomy, appendectomy, surgery for piriformis syndrome, sacroiliac joint fusion with implanted cages, fusion of degenerative discs in the adjacent spine, coccygectomy, and urinary bladder procedures (Fig. 115-4).