CHAPTER 20

The Autonomic Nervous System

The autonomic (visceral) nervous system (ANS) is concerned with control of target tissues: the cardiac muscle, the smooth muscle in blood vessels and viscera, and the glands. It helps maintain a constant internal body environment (homeostasis). The ANS consists of efferent pathways, afferent pathways, and groups of neurons in the brain and spinal cord that regulate the system’s functions. Autonomic reflex activity in the spinal cord accounts for some aspects of autonomic regulation and homeostasis. However, it is modulated by supraspinal centers such as brain stem nuclei and the hypothalamus, so that there is a hierarchical organization within the central nervous system itself.

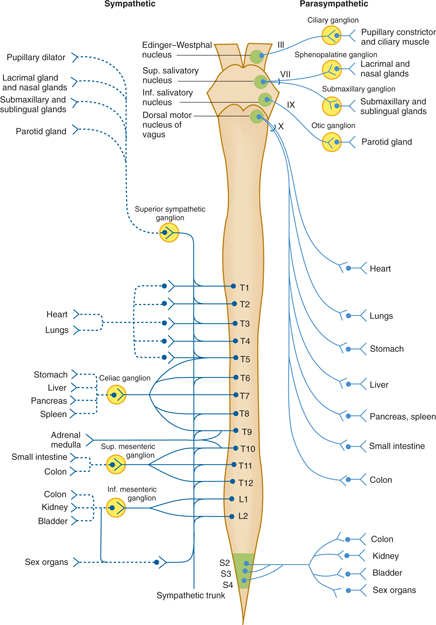

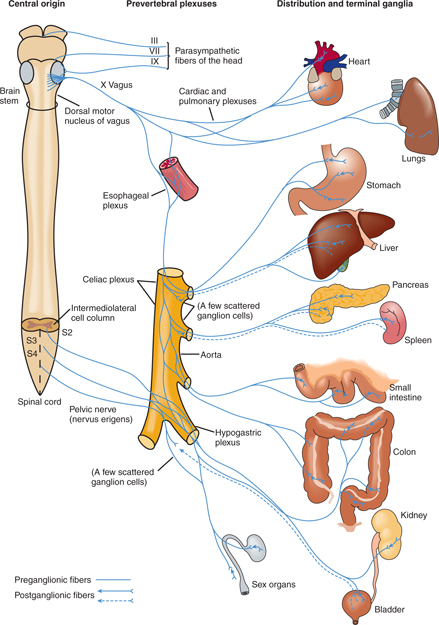

The ANS is divided into two major anatomically distinct divisions that have opposing actions: the sympathetic (thoracolumbar) and parasympathetic (craniosacral) divisions (Fig 20–1). The sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions of the ANS are anatomically distinct from each other, and are also different in terms of their pharmacological properties, that is, their response to medications. Thus, they are sometimes referred to as the sympathetic nervous system and the parasympathetic nervous system. The critical importance of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems is underscored by the fact that many commonly used medications (eg, medications for treating high blood pressure, for regulating gastrointestinal function, or for maintaining a regular heart beat) have their major actions on neurons within these systems.

FIGURE 20–1 Overview of the sympathetic nervous system and of its sympathetic (thoracolumbar) and parasympathetic (craniosacral) divisions. Inf., inferior; Sup., superior.

Some authorities consider the intrinsic neurons of the gut as forming a separate enteric nervous system.

AUTONOMIC OUTFLOW

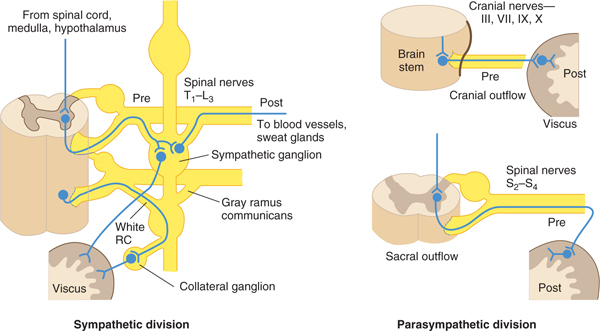

The efferent components of the autonomic system are organized into sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions, which arise from preganglionic cell bodies in different locations.

The autonomic outflow system is organized more diffusely than the somatic motor system. In the somatic motor system, lower motor neurons project directly from the spinal cord or brain, without an interposed synapse, to innervate a relatively small group of target cells (somatic muscle cells). This permits individual muscles to be activated separately so that motor action is finely tuned. In contrast, a more slowly conducting two-neuron chain characterizes the autonomic outflow. The cell body of the primary neuron (the presynaptic, or preganglionic, neuron) within the central nervous system is located in the intermediolateral gray column of the spinal cord or in the brain stem nuclei. It sends its axon, which is usually a small-diameter, myelinated B fiber (see Chapter 3), out to synapse with the secondary neuron (the postsynaptic, or postganglionic, neuron) located in one of the autonomic ganglia. From there, the postganglionic axon passes to its terminal distribution in a target organ. Most postganglionic autonomic axons are unmyelinated C fibers.

The autonomic outflow system projects widely to most target tissues and is not as highly focused as the somatic motor system. Because the postganglionic fibers outnumber the preganglionic neurons by a ratio of about 32:1, a single preganglionic neuron may control the autonomic functions of a rather extensive terminal area.

Sympathetic Division

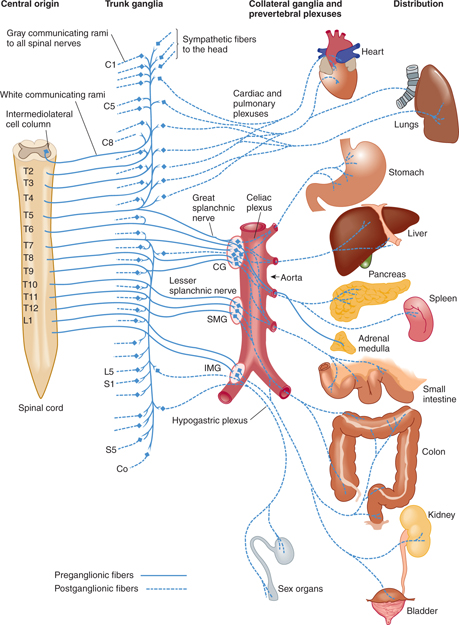

The sympathetic nervous system, or sympathetic (thoracolumbar) division of the ANS arises from preganglionic cell bodies located in the intermediolateral cell columns of the 12 thoracic segments and the upper two lumbar segments of the spinal cord (Fig 20–2).

FIGURE 20–2 Sympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system (left half). CG, celiac ganglion; IMG, inferior mesenteric ganglion; SMG, superior mesenteric ganglion.

A. Preganglionic Sympathetic Efferent Fiber System

Preganglionic fibers are mostly myelinated. Coursing with the ventral roots, they form the white communicating rami of the thoracic and lumbar nerves, through which they reach the ganglia of the sympathetic chains or trunks (Fig 20–3). These trunk ganglia lie on the lateral sides of the bodies of the thoracic and lumbar vertebrae. On entering the ganglia, the fibers may synapse with ganglion cells, pass up or down the sympathetic trunk to synapse with ganglion cells at a higher or lower level, or pass through the trunk ganglia and out to one of the collateral (intermediary) sympathetic ganglia (eg, the celiac and mesenteric ganglia).

FIGURE 20–3 Types of outflow in autonomic nervous system. Pre, preganglionic neuron; Post, postganglionic neuron; CR, communicating ramus. (Reproduced, with permission, from Ganong WF: Review of Medical Physiology, 22nd ed. McGraw-Hill, 2005.)

The splanchnic nerves arising from the lower seven thoracic segments pass through the trunk ganglia to the celiac and superior mesenteric ganglia. There, synaptic connections occur with ganglion cells whose postganglionic axons then pass to the abdominal viscera via the celiac plexus. The splanchnic nerves arising from spinal cord segments in the lowest thoracic and upper lumbar region convey fibers to synaptic stations in the inferior mesenteric ganglion and to small ganglia associated with the hypogastric plexus, through which postsynaptic fibers are distributed to the lower abdominal and pelvic viscera.

B. The Adrenal Gland

Preganglionic sympathetic axons in the splanchnic nerves also project to the adrenal gland, where they synapse on chromaffin cells in the adrenal medulla. The adrenal chromaffin cells, which receive direct synaptic input from preganglionic sympathetic axons, are derived from neural crest and can be considered to be modified postganglionic cells that have lost their axons.

C. Postganglionic Efferent Fiber System

The mostly unmyelinated postganglionic sympathetic fibers form the gray communicating rami. The fibers may course with the spinal nerve for some distance or go directly to their target tissues.

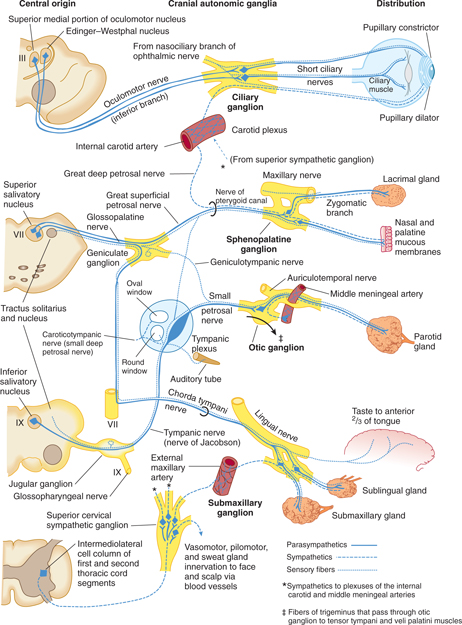

The gray communicating rami join each of the spinal nerves and distribute the vasomotor, pilomotor, and sweat gland innervation throughout the somatic areas. Branches of the superior cervical sympathetic ganglion enter into the formation of the sympathetic carotid plexuses around the internal and external carotid arteries for distribution of sympathetic fibers to the head (Fig 20–4). After exiting from the carotid plexus, these postganglionic sympathetic axons project to the salivary and lacrimal glands, the muscles that dilate the pupil and raise the eyelid, and sweat glands and blood vessels of the face and head.

FIGURE 20–4 Autonomic nerves to the head.

The superior cardiac nerves from the three pairs of cervical sympathetic ganglia pass to the cardiac plexus at the base of the heart and distribute cardioaccelerator fibers to the myocardium. Vasomotor branches from the upper five thoracic ganglia pass to the thoracic aorta and to the posterior pulmonary plexus, through which dilator fibers reach the bronchi.

Parasympathetic Division

The parasympathetic nervous system or parasympathetic (craniosacral) division of the ANS arises from preganglionic cell bodies in the gray matter of the brain stem (medial part of the oculomotor nucleus, Edinger- Westphal nucleus, superior and inferior salivatory nuclei) and the middle three segments of the sacral cord (S2–4) (Figs 20–3 and 20–5). Most preganglionic fibers from S2, S3, and S4 run without interruption from their central origin within the spinal cord to either the wall of the viscus they supply or the site where they synapse with terminal ganglion cells associated with the plexuses of Meissner and Auerbach in the wall of the intestinal tract (see Enteric Nervous System section). Because the parasympathetic postganglionic neurons are located close to the tissues they supply, they have relatively short axons. The parasympathetic distribution is confined entirely to visceral structures.

FIGURE 20–5 Parasympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system (only left half shown).

Four cranial nerves convey preganglionic parasympathetic (visceral efferent) fibers. The oculomotor, facial, and glossopharyngeal nerves (cranial nerves III, VII, and IX) distribute parasympathetic or visceral efferent fibers to the head (see Fig 20–4 and Chapters 7 and 8). Parasympathetic axons in these nerves synapse with postganglionic neurons in the ciliary, sphenopalatine, submaxillary, and otic ganglia, respectively (see Autonomic Innervation of the Head section).

The vagus nerve (cranial nerve X) distributes its autonomic fibers to the thoracic and abdominal viscera via the prevertebral plexuses. The pelvic nerve (nervus erigentes) distributes parasympathetic fibers to most of the large intestine and to the pelvic viscera and genitals via the hypogastric plexus.

Autonomic Plexuses

The autonomic plexuses are a large network of nerves that serve a conduit for the distribution of the sympathetic and parasympathetic (and afferent) fibers that enter into their formation (see Figs 20–1, 20–2, and 20–5).

The cardiac plexus, located about the bifurcation of the trachea and roots of the great vessels at the base of the heart, is formed from the cardiac sympathetic nerves and cardiac branches of the vagus nerve, which it distributes to the myocardium and the vessels leaving the heart.

The right and left pulmonary plexuses are joined with the cardiac plexus and are located about the primary bronchi and pulmonary arteries at the roots of the lungs. They are formed from the vagus and the upper thoracic sympathetic nerves and are distributed to the vessels and bronchi of the lung.

The celiac (solar) plexus is located in the epigastric region over the abdominal aorta. It is formed from vagal fibers reaching it via the esophageal plexus, sympathetic fibers arising from celiac ganglia, and sympathetic fibers coursing down from the thoracic aortic plexus. It projects to most of the abdominal viscera, which it reaches by way of numerous subplexuses, including phrenic, hepatic, splenic, superior gastric, suprarenal, renal, spermatic or ovarian, abdominal aortic, and superior and inferior mesenteric plexuses.

The hypogastric plexus is located in front of the fifth lumbar vertebra and the promontory of the sacrum. It receives sympathetic fibers from the aortic plexus and lumbar trunk ganglia and parasympathetic fibers from the pelvic nerve. Its two lateral portions, the pelvic plexuses, lie on either side of the rectum. It projects to the pelvic viscera and genitals via subplexuses that extend along the visceral branches of the hypogastric artery. These subplexuses include the middle hemorrhoidal plexus, to the rectum; the vesical plexus, to the bladder, seminal vesicles, and ductus deferens; the prostatic plexus, to the prostate, seminal vesicles, and penis; the vaginal plexus, to the vagina and clitoris; and uterine plexus, to the uterus and uterine tubes.

AUTONOMIC INNERVATION OF THE HEAD

The autonomic supply to visceral structures in the head deserves special consideration (see Fig 20–4). The skin of the face and scalp (smooth muscle, glands, and vessels) receives postsynaptic sympathetic innervation only, from the superior cervical ganglion via the carotid plexus, which extends along the branches of the external carotid artery. The deeper structures (intrinsic eye muscles, salivary glands, and mucous membranes of the nose and pharynx), however, receive a dual autonomic supply from the sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions. The supply is mediated by the internal carotid plexus (postganglionic sympathetic innervation from the superior cervical plexus) and the visceral efferent fibers in four pairs of cranial nerves (parasympathetic innervation).

There are four pairs of autonomic ganglia—ciliary, pterygopalatine, otic, and submaxillary—in the head (see Fig 20–4). Each ganglion receives a sympathetic, a parasympathetic, and a sensory root (a branch of the trigeminal nerve). Only the parasympathetic fibers make synaptic connections within these ganglia, which contain the cell bodies of the postganglionic parasympathetic fibers. The sympathetic and sensory fibers pass through these ganglia without interruption.

CLINICAL CORRELATIONS