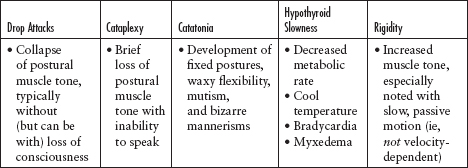

1 THE BODY LANGUAGE OF MOVEMENT DISORDERS Movement is controlled by a highly evolved and sophisticated system of interacting circuits in the nervous system that allow human thought to be expressed! Because of this level of sophistication, disorders affecting the control of movement may have a plethora of manifestations. The treatment of movement disorders is a subspecialty of neurology concerned with patients who move either “too much” or “too little.”1 Therefore, movement disorders are neurological syndromes in which there is either an excess of movement (hyperkinesia) or a paucity of voluntary and automatic movements (hypokinesia) that is unrelated to weakness or spasticity.2 Movement disorders are quite common. Before the recognition of restless legs syndrome (RLS), the most common movement disorder was essential tremor (ET). The estimated prevalence rates of the most common movement disorders per 100,000 of the general population are listed in Table 1.1.3 The approach to a patient with a movement disorder, like that to a patient with any other condition, begins with taking the history of the illness (Figure 1.1). Then, the examination of a patient with a movement disorder depends on careful observation. Movement Disorder Prevalence Restless legs syndrome 9,800 Essential tremor 415 Parkinson’s disease 187 Tourette syndrome 29–1,052 Primary torsion dystonia 33 Hemifacial spasm 7.4–14.5 Blepharospasm 13.3 Hereditary ataxia 6 Huntington’s disease 2–12 Wilson’s disease 3 Progressive supranuclear palsy 2–6.4 Multiple systems atrophy 4.4 Source: Adapted from Ref. 3: Schrag A. Epidemiology of movement disorders. In: Jankovic J, Tolosa E, eds. Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002:73–89. Patients with hypokinetic disorders present with a paucity of symptoms and are often best observed while they are unaware that their examination has already begun. For example, patients can be observed from the time they enter the room to the moment when they reach the chair or examination table. Verbal prompting, although a standard part of examinations, may cause patients’ movements to be faster (or slower) than those of their usual state. Figure 1.1 Figure 1.2 Akinesia, bradykinesia, and hypokinesia literally mean “absence,” “slowness,” and “decreased amplitude” of movement, respectively. The three terms are commonly grouped together for convenience, and the conditions they describe are usually referred to collectively as bradykinesia (Figure 1.3).2 Parkinsonism is the most common cause of hypokinesia, but there are other, less common causes, such as cataplexy and drop attacks, catatonia, hypothyroid slowness, rigidity, and stiff muscles (Table 1.2). Hypokinetic movements may be further subdivided into those with parkinsonian or nonparkinsonian etiologies (Figure 1.4). Parkinsonism is the most recognized form of hypokinesia and accounts for about half of all hypokinetic movement disorders. Figure 1.3 Table 1.2 Hyperkinetic Disorders Hypokinetic Disorders Common Common Chorea Parkinsonism Dystonia Myoclonus Restless legs syndrome Tremor Tic Less common Abdominal dyskinesia Akathitic movements Ataxia/asynergia/dysmetria Athetosis Ballism Hemifacial spasm Hyperekplexia Hypnogenic dyskinesia Jumping disorders Jumpy stumps Movement of toes and fingers Myokymia and synkinesis Myorhythmia Paroxysmal dyskinesia Periodic movements in sleep REM sleep behavior disorder Stereotypy Less common Apraxia Blocking (holding) tics Cataplexy and drop attacks Catatonia, psychomotor depression, and obsessional slowness Freezing phenomenon Hesitant gaits Hypothyroid slowness Rigidity Stiff muscles Figure 1.4 Figure 1.5 Drop attacks are sudden falls that occur with or without a loss of consciousness. They are caused by either a collapse of postural muscle tone or an abnormal contraction of the leg muscles during ambulation or standing. Cataplexy is another cause of symptomatic drop attacks. Patients fall suddenly without a loss of consciousness, but with the inability to speak during an attack. Catatonia is a syndrome (not a specific diagnosis) that is characterized by catalepsy (development of fixed postures), waxy flexibility (retention of limbs for an indefinite period of time in the position in which is they are placed), and mutism. It can also be associated with bizarre mannerisms. Hypothyroid slowness can be mistaken for parkinsonism. Additional clues, such as decreased metabolic rate, cool temperature, bradycardia, myxedema, and a lack of the rigidity and resting tremors seen in parkinsonism, should suggest the diagnosis (see Table 1.3). Table 1.3 To help determine the phenomenology of hyperkinetic movement disorders, evaluate features such as rhythmicity, speed, duration, and movement pattern (eg, repetitive, flowing, continual, paroxysmal, diurnal). Figure 1.6 Table 1.4 Chorea Involuntary, irregular, purposeless, nonrhythmic, often abrupt, rapid, and unsustained movements seem to flow randomly from one body part to another; they are unpredictable in timing, direction, and distribution. Dystonia Both agonist and antagonist muscles of a body region contract simultaneously to produce a twisted posture of the limb, neck, or trunk. In contrast to chorea, dystonic movements repeatedly involve the same group of muscles. They do not necessarily flow or affect different muscle groups randomly. Myoclonus Sudden, brief, shocklike jerks are caused by muscular contraction (positive myoclonus) or inhibition (negative myoclonus, such as asterixis). Restless legs syndrome An unpleasant, crawling sensation in the legs (or arms), particularly during sitting and relaxation, is most prominent in the evening (but can also occur during the day). It disappears (or is significantly relieved) during ambulation. Tics Abnormal, stereotypic, repetitive movements (motor tics) or abnormal sounds (phonic tics) can be suppressed temporarily but may need to be “released” at some point. The release provides internal “relief” to the patient until the next “urge” is felt. Tremor An oscillatory, usually rhythmic (to-and-fro) movement of one or more body parts, such as the neck, tongue, chin, or vocal cords or a limb. The rate, location, amplitude, and constancy vary depending on the specific type of tremor. • Resting tremor • Postural/sustention tremor • Action/intention tremor

Most, but not all, movement disorders result from some element of basal ganglia dysfunction and are sometimes termed extrapyramidal disorders.

Most, but not all, movement disorders result from some element of basal ganglia dysfunction and are sometimes termed extrapyramidal disorders.

However, movement disorders can also result from injury to the cerebral cortex, cerebellum, brainstem, spinal cord, peripheral nerves, and other elements of the central and peripheral nervous system.

However, movement disorders can also result from injury to the cerebral cortex, cerebellum, brainstem, spinal cord, peripheral nerves, and other elements of the central and peripheral nervous system.

PREVALENCE OF MOVEMENT DISORDERS

APPROACH TO THE PATIENT WITH A MOVEMENT DISORDER

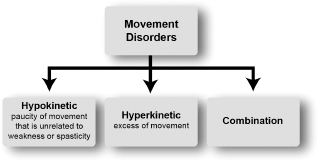

The first task should be to determine whether the phenomenon represents too little movement (hypokinesia) or too much movement (hyperkinesia) (Figure 1.2).

The first task should be to determine whether the phenomenon represents too little movement (hypokinesia) or too much movement (hyperkinesia) (Figure 1.2).

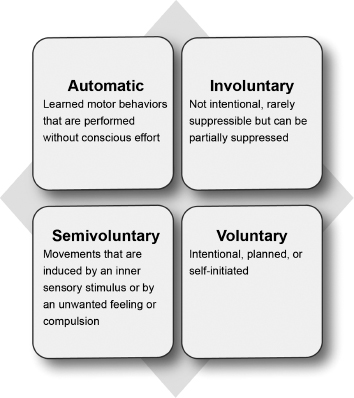

If the patient is hyperkinetic, the next question to be answered is whether the extraneous movements are involuntary, voluntary, or “semivoluntary.”

If the patient is hyperkinetic, the next question to be answered is whether the extraneous movements are involuntary, voluntary, or “semivoluntary.”

It should be noted that as a general rule, abnormal involuntary movements, including those with an organic etiology, are exaggerated by anxiety, and most diminish or disappear during sleep.2

It should be noted that as a general rule, abnormal involuntary movements, including those with an organic etiology, are exaggerated by anxiety, and most diminish or disappear during sleep.2

HYPOKINETIC DISORDERS

Features worth extracting from the patient’s history.

Classification of movement disorders.

Bradykinesia is one of the cardinal motor features of parkinsonism.

Bradykinesia is one of the cardinal motor features of parkinsonism.

These motor features are elicited during voluntary tasks and may also be seen when the automatic or “unvoluntary” movements associated with learned tasks are observed.

These motor features are elicited during voluntary tasks and may also be seen when the automatic or “unvoluntary” movements associated with learned tasks are observed.

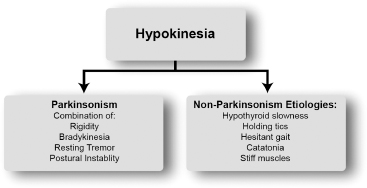

It manifests as any combination of its four cardinal motor features: resting tremor, bradykinesia (slowness in movement), rigidity (stiffness), and gait/postural instability.

It manifests as any combination of its four cardinal motor features: resting tremor, bradykinesia (slowness in movement), rigidity (stiffness), and gait/postural instability.

Not all four motor features need to be present. At least two of the cardinal features need to be present, with one of them being resting tremor or bradykinesia, before the diagnosis of parkinsonism is made.

Not all four motor features need to be present. At least two of the cardinal features need to be present, with one of them being resting tremor or bradykinesia, before the diagnosis of parkinsonism is made.

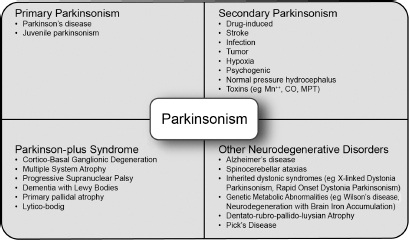

There are several forms of parkinsonism, which can be broadly categorized as primary, secondary, parkinson-plus, and heredodegenerative disorders (Figure 1.5).

There are several forms of parkinsonism, which can be broadly categorized as primary, secondary, parkinson-plus, and heredodegenerative disorders (Figure 1.5).

In general, primary parkinsonism (ie, idiopathic Parkinson’s disease) is a progressive, neurodegenerative, almost “purely” parkinsonian disorder of unclear etiology. Sometimes, this diagnosis can be made only after other causes of parkinsonism have been systematically excluded. It is probably the most common form of parkinsonism.

In general, primary parkinsonism (ie, idiopathic Parkinson’s disease) is a progressive, neurodegenerative, almost “purely” parkinsonian disorder of unclear etiology. Sometimes, this diagnosis can be made only after other causes of parkinsonism have been systematically excluded. It is probably the most common form of parkinsonism.

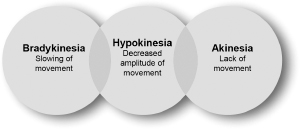

The spectrum of bradykinesia.

Phenomenology of Movement Disorders

Classification of hypokinetic disorders according to the presence or absence of parkinsonism.

Classification of parkinsonism according to etiology.

Secondary parkinsonism refers to parkinsonism with an identifiable cause, such as drug-induced parkinsonism (eg, by dopamine receptor blockers like antipsychotic and antiemetic drugs) or parkinsonism resulting from a stroke (vascular parkinsonism), infection (postencephalitic parkinsonism), or tumors in the basal ganglia.

Secondary parkinsonism refers to parkinsonism with an identifiable cause, such as drug-induced parkinsonism (eg, by dopamine receptor blockers like antipsychotic and antiemetic drugs) or parkinsonism resulting from a stroke (vascular parkinsonism), infection (postencephalitic parkinsonism), or tumors in the basal ganglia.

Parkinson-plus syndromes are progressive neurodegenerative disorders in which parkinsonism is the main but not the only feature. Examples of Parkinson-plus disorders are the following: progressive supranuclear palsy, often presenting with early dementia, vertical gaze palsy, and frequent falls at disease onset; multiple system atrophy, characteristically presenting with a lack of tremor, relatively prominent cerebellar features (eg, ataxia and incoordination), significant autonomic dysfunction (eg, urinary incontinence, erectile dysfunction, orthostatic hypotension), and pyramidal features (eg, turned-up toes and spasticity); and corticobasoganglionic degeneration or corticobasal degeneration, presenting with early dementia, cortical sensory loss, apraxia, limb dystonia, and “alien limb phenomenon” characterized by autonomous movements of a limb.

Parkinson-plus syndromes are progressive neurodegenerative disorders in which parkinsonism is the main but not the only feature. Examples of Parkinson-plus disorders are the following: progressive supranuclear palsy, often presenting with early dementia, vertical gaze palsy, and frequent falls at disease onset; multiple system atrophy, characteristically presenting with a lack of tremor, relatively prominent cerebellar features (eg, ataxia and incoordination), significant autonomic dysfunction (eg, urinary incontinence, erectile dysfunction, orthostatic hypotension), and pyramidal features (eg, turned-up toes and spasticity); and corticobasoganglionic degeneration or corticobasal degeneration, presenting with early dementia, cortical sensory loss, apraxia, limb dystonia, and “alien limb phenomenon” characterized by autonomous movements of a limb.

Other neurodegenerative disorders can also present with parkinsonism. The main difference between this group of disorders and the parkinson-plus disorders is that parkinsonism is not their most prominent feature. For example, Alzheimer disease is primarily a neurodegenerative disorder of memory dysfunction, but parkinsonism can occur at the later stages of the illness.

Other neurodegenerative disorders can also present with parkinsonism. The main difference between this group of disorders and the parkinson-plus disorders is that parkinsonism is not their most prominent feature. For example, Alzheimer disease is primarily a neurodegenerative disorder of memory dysfunction, but parkinsonism can occur at the later stages of the illness.

About two-thirds of cases of drop attacks are of unclear etiology.

About two-thirds of cases of drop attacks are of unclear etiology.

Known causes include epilepsy, myoclonus, startle reactions, and structural central nervous system lesions (eg, cervical cord pathology from disk disease).

Known causes include epilepsy, myoclonus, startle reactions, and structural central nervous system lesions (eg, cervical cord pathology from disk disease).

Syncope is the most common nonneurological cause (Table 1.3).

Syncope is the most common nonneurological cause (Table 1.3).

There is often a preceding trigger, usually laughter or a sudden emotional stimulus.

There is often a preceding trigger, usually laughter or a sudden emotional stimulus.

Cataplexy is one of the four cardinal features of narcolepsy, along with excessive sleepiness, sleep paralysis, and hypnagogic hallucinations (see Table 1.3).

Cataplexy is one of the four cardinal features of narcolepsy, along with excessive sleepiness, sleep paralysis, and hypnagogic hallucinations (see Table 1.3).

Patients remain in one position for hours and move exceedingly slowly in response to commands, but when they move spontaneously (eg, scratch themselves), they do so quickly.

Patients remain in one position for hours and move exceedingly slowly in response to commands, but when they move spontaneously (eg, scratch themselves), they do so quickly.

Catatonia is classically a feature of schizophrenia but can also occur with severe depression, hysterical disorders, and even organic brain disease (see Table 1.3).

Catatonia is classically a feature of schizophrenia but can also occur with severe depression, hysterical disorders, and even organic brain disease (see Table 1.3).

Features of Other Nonparkinsonian Hypokinetic Movements

HYPERKINETIC DISORDERS

Hyperkinetic movements can be described based on how they are induced (ie, stimuli, action, exercise); the complexity of the movements (complex or simple); and their suppressibility (by volitional attention or by “sensory tricks”).

Hyperkinetic movements can be described based on how they are induced (ie, stimuli, action, exercise); the complexity of the movements (complex or simple); and their suppressibility (by volitional attention or by “sensory tricks”).

Movement categories based on volition.

The description of a hyperkinetic movement disorder should always identify which body parts are involved.2

The description of a hyperkinetic movement disorder should always identify which body parts are involved.2

As mentioned earlier, it is important to note that not all hyperkinetic movements are involuntary. Hyperkinetic (or hypokinetic) movements can be seen in four major states: automatic, voluntary, semivoluntary (eg, as in RLS or akathisia), and involuntary (Figure 1.6).

As mentioned earlier, it is important to note that not all hyperkinetic movements are involuntary. Hyperkinetic (or hypokinetic) movements can be seen in four major states: automatic, voluntary, semivoluntary (eg, as in RLS or akathisia), and involuntary (Figure 1.6).

Common hyperkinetic disorders include RLS, dystonia, chorea, tics, myoclonus, and tremors (Table 1.4).

Common hyperkinetic disorders include RLS, dystonia, chorea, tics, myoclonus, and tremors (Table 1.4).

Characteristics of the Most Common Types of Hyperkinetic Disorders

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Neupsy Key

Fastest Neupsy Insight Engine