The Brain-Injured or Developmentally Disabled Psychiatric Inpatient

David B. Arciniegas

Alan C. Anderson

The neuropsychiatric consequences of acquired brain injury (ABI) and developmental disabilities (DD) are many and varied and include problems such as depression, mania, affective lability, anxiety, apathy, psychosis, aggression, agitation, and self-injurious behavior. Neuropsychiatric disorders may arise in this population as a direct physiologic consequence of ABI or DD, an independent comorbid psychiatric condition, a manifestation of environmental or psychosocial problems, or a combination of these factors. When neuropsychiatric problems develop in a person with ABI or DD, they may be difficult to identify correctly because of the cognitive and communication problems often experienced by these individuals.1 This difficulty is often compounded by the sometimes atypical presentations of neuropsychiatric conditions in this population, which frequently cross conventional psychiatric diagnostic boundaries or occur only in partial forms.2 Consequently, the task of evaluating and treating neuropsychiatric problems in persons with ABI and DD is necessarily complex. Unfortunately, most psychiatrists are afforded little experience in care of persons with ABI and DD during medical school or residency training.3, 4, 5 Despite suggestions that psychiatric training should require experience in the management of persons with DD,6,7 the availability of supervised clinical experience in this area during residency remains highly variable and is in many cases optional.3 Calls for similar experience in the neuropsychiatric management of persons with ABI and DD are either embedded in the suggested curriculum for psychosomatic medicine rotations8 or instead incorporated specifically into fellowship-level curricula.9,10

Nonetheless, the high prevalence of ABI and DD, which collectively affect >5% of the US population,11,12 and the high rates of severe neuropsychiatric disorders associated with these conditions13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 all but ensure that inpatient psychiatrists will be called upon to participate in the care of persons with DD and ABI.

A complete review of the ABI and DD and their neuropsychiatric features is beyond the scope of this chapter, which may be supplemented by information presented elsewhere.20, 21, 22 Because the goal is to offer inpatient psychiatrists practical guidance on the management of neuropsychiatric problems in persons with ABI and DD, the authors discuss the etiology and pathogenesis of ABI and DD only in general terms except where a more detailed understanding of these matters informs their treatments.

Definitions of Acquired Brain Injury and Developmental Disability

ACQUIRED BRAIN INJURY

ABI is a broad category that refers to any noncongenital, nondegenerative injury to the brain. The causes of ABI are numerous and include trauma, hypoxia, vascular disruption, infections, inflammatory or demyelinating conditions, cerebral neoplasms (primary or metastatic), metabolic and nutritional disorders, endocrine disturbances, toxic exposures, substance abuse or dependence, some chemotherapies, and electrical injuries. From a practical standpoint, ABI implies the development of a static or potentially reversible neurologic condition that results in cognition, emotional, behavioral, and/or

physical impairments which interfere with the ability to function independently in the absence of special services, support, or other forms of assistance.

physical impairments which interfere with the ability to function independently in the absence of special services, support, or other forms of assistance.

Neurodegenerative conditions are generally excluded from the category of ABI based on their progressive, rather than static or potentially reversible, nature. Similarly, some clinicians might exclude inflammatory disorders (e.g., multiple sclerosis [MS], progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy), infectious diseases (e.g., human immunodeficiency virus [HIV]), cerebral neoplasms (e.g., primary or metastatic), some cerebrovascular diseases (e.g., Binswanger disease, cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy [CADASIL]), and other progressive neurologic conditions from the category of ABI.

Notwithstanding arguments regarding the boundaries of this category, the authors suggest that an inclusive formulation of ABI is often the most practical one by which to help patients, their families, and other health care providers understand the role of structural and/or functional brain disturbances on the development and treatment of neuropsychiatric problems. Traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) and hypoxic-ischemic (anoxic) brain injuries, however, are the most common intended referents of ABI in the medical literature. Most studies of treatments for the neuropsychiatric consequences of ABI are conducted in these contexts, and particularly in the setting of TBI. In the authors’ experience, the principles of evaluation and treatment of persons with neuropsychiatric problems following TBI generalize reasonably well to the broader category of ABI. Treatment recommendations offered in this chapter therefore draw heavily upon this literature.

Obviously, some patients require condition-specific treatments (e.g., immunomodulatory therapies in demyelinating disorders, antiviral therapies in HIV, chemo- or radiotherapies in cerebral neoplasms, antispasticity therapies, etc.) that influence the selection or dosing of psychopharmacologic agents. In the less common context of recurrent or long-term inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations, or when presented with the opportunity to establish realistic long-term management strategies with the patient and his or her care providers, the treating psychiatrist also may be able to offer treatment recommendations that anticipate needs entailed by the natural course of a specific ABI.

Persons of any age may develop a condition that merits the designation ABI. However, when one or more of these conditions develop before the age of 22, they are most often discussed under the rubric of DD.

DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITY

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services-Administration for Children and Families (USDHHS-ACF)23 defines DD as a severe chronic disability attributable to a mental and/or physical impairment acquired before 22 years that results in substantial functional limitations in three or more areas of major life activity. These areas include self-care, receptive and expressive language, learning, mobility, self-direction, capacity for independent living, and economic self-sufficiency. This formulation of DD also requires that such limitations reflect the need for services, individualized supports, or other forms of assistance that are of lifelong or extended duration and that require individual planning and coordination. The category of DD also includes individuals from birth to 9 years of age with substantial developmental delays or specific congenital or acquired conditions who, while not presently suffering substantial functional limitations in three or more of the above-mentioned areas, have a high probability of developing such limitations later in life.

Many administrative formulations of DD require an impairment of intellectual function resulting in a full-scale intelligence quotient (IQ) of 70 (two standard deviations below age-adjusted performance expectations) or less. While such formulations may assist with the allocation of publicly funded services, the neuropsychiatric treatment needs of patients with milder intellectual impairments or substantial impairments in adaptive behavior resulting from communicative disorders, behavioral disturbances, or physical (including sensory) impairments may benefit from a diagnostic and treatment approach that defines DD more broadly.

The causes of DD include chromosomal abnormalities, other genetic factors, prenatal and perinatal neurodevelopmental insults, childhood ABIs, environmental exposures, and sociocultural factors.24 These and other factors contribute to the broad array of clinical diagnoses that are grouped under the heading of DD. The most common of these clinical diagnoses are mental retardation, cerebral palsy, epilepsy, autism, sensory (vision, hearing) or communicative disorders, and other childhood-onset

neurologic conditions that result in impairment of general intellectual functioning or adaptive behavior.

neurologic conditions that result in impairment of general intellectual functioning or adaptive behavior.

When the specific cause of DD in an individual patient is known, the treatment of the acute neuropsychiatric problems with which that patient presents may require modification tailored to concurrently administered medical or neurologic treatments (e.g., anticonvulsants in epilepsy, endocrine or metabolic therapies, etc.). In many cases, despite a thorough evaluation, the etiology of the patient’s DD will either be unclear (cryptogenic) or presumed to bemultifactorial. Accordingly, the neuroanatomy and putative neurochemistry of both the DD and its neuropsychiatric sequelae often remain a source of uncertainty, particularly as regards their implications for psychopharmacologic interventions. A general approach to the evaluation and treatment of the neuropsychiatric manifestations of DD, similar to that offered for the psychiatric management of persons with ABI, is therefore often the most practical strategy available to the inpatient psychiatrists providing care to patients with DD.

General Principles of Evaluation and Treatment

NEUROPSYCHIATRIC EVALUATION

Before initiating any treatment of the patient with ABI or DD, obtaining a thorough developmental, neurologic, psychiatric (including substance), social, family, and treatment history is essential. In general, the initial inpatient evaluation of persons with ABI and DD is similar to that of patients with primary psychiatric illnesses. However, Silka and Hauser24 offer several additional recommendations with which to adjust this evaluation for the needs of this population.

The evaluation should be conducted promptly to avoid escalating behavioral disturbances due to the unfamiliar and often intense milieu, of the inpatient psychiatric setting. The evaluation is best conducted in as safe, private, and quiet environment as is feasible. If the patient is accompanied by caregivers or professional staff that the patient usually finds comforting, inviting them into the interview may be useful. Conversely, if the initial evaluation suggests that the presence of such individuals is distressing or disruptive to the patient, excusing them from the interview of the patient may be necessary.

As with any patient, the presenting problem should be identified as clearly as possible. In this population, defining clearly the presenting problem is sometimes more challenging than among patients with primary psychiatric illnesses. Patients with ABI and DD and their caregivers may be biased to under- or overreport psychiatric symptoms.1,26,27 Limited awareness regarding the pathological nature of some behaviors, fear of stigmatization associated with psychiatric diagnoses, attempts to avoid impugning the efforts of other care providers, and pessimism regarding the effectiveness or tolerability of treatment may result in caregivers’ minimizing or withholding potentially important historical details. Conversely, frustration over or intolerance of challenging behaviors may result in magnification of the reported severity of such symptoms and requests for prescription of psychiatric medications that are in fact unnecessary.25

The initial evaluation should also seek not only neuropsychiatric symptoms but also potential causes or contributors, including medical, neurologic, psychiatric, substance, and environmental factors, as well as current treatments (discussed further in the subsequent text) and the individuals providing them. With regard to this latter issue, clinicians should be mindful that a change in residence, the residents or caregivers in that residence, disruptions of daily routines, or other similar events may produce acute emotional and/or behavioral disturbances among persons with ABI and DD. Clinicians also should be vigilant for signs of abuse or maltreatment of patients with ABI and DD, particularly among those who are able to communicate their distress only by their behavior and among those whose unwanted behaviors may engender further abuse.28, 29, 30 Although pharmacologic treatment may be required to address the emotional or behavioral consequences of environmental problems, sometimes the most appropriate recommendation will be to use no medicines at all if a change in the environment or the provision of nonpharmacologic interventions (e.g., supportive psychotherapy, staff retraining, change in caregivers, etc.) will suffice.

Finally, observations made of the patient at the time of admission must be regarded as preliminary; placed suddenly in the unfamiliar emergency or inpatient psychiatric ward, patients may behave quite

differently (better or worse) from how they behave in their usual environment. Additionally, the frequently severe cognitive, behavioral, and communication impairments experienced by persons with ABI or DD, as well as the often limited availability of collateral history from reliable informants and medical records, may make it difficult to arrive at a well-informed diagnosis, and therefore a rational treatment plan, at the time of admission to a psychiatric unit. With this in mind, remaining circumspect with respect to diagnosis and treatment until the presenting problem and the context in which it occurs are characterized fully is prudent.

differently (better or worse) from how they behave in their usual environment. Additionally, the frequently severe cognitive, behavioral, and communication impairments experienced by persons with ABI or DD, as well as the often limited availability of collateral history from reliable informants and medical records, may make it difficult to arrive at a well-informed diagnosis, and therefore a rational treatment plan, at the time of admission to a psychiatric unit. With this in mind, remaining circumspect with respect to diagnosis and treatment until the presenting problem and the context in which it occurs are characterized fully is prudent.

CHARACTERIZING NEUROPSYCHIATRIC SYMPTOMS

For many of the reasons noted earlier, characterizing neuropsychiatric symptoms requiring treatment among persons with ABI and DD presents substantial challenges to the inpatient psychiatrist. These challenges may, at least in part, be overcome by the use of objective rating scales of neuropsychiatric status. In addition to facilitating the timely identification of neuropsychiatric symptoms requiring clinical intervention, use of such scales provides a means by which to develop a common frame of reference for discussion of neuropsychiatric symptoms between the inpatient psychiatrist, the patient, and other parties involved in the patient’s care. They also serve as a reference to measure the response to pharmacologic and behavioral interventions.

When the patient with ABI or DD is cognitively and linguistically capable of participating in a structured clinical interview of neuropsychiatric functioning, the Neurobehavioral Rating Scale-Revised (NRS-R)31 is particularly well suited to this task. Derived from the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale,32 a widely used psychiatric research assessment, the NRS-R includes 29 items that assess five domains of neuropsychiatric function: cognition, positive symptoms, negative symptoms, mood and affect, and oral/motor function. Completing the interview portion of the NRS-R typically requires only 15 to 20 minutes. During the interview, structured clinical observations are made and then supplemented by collateral data gathered from reliable informants on the patient’s day-to-day functioning. This relatively brief assessment thereby provides the clinician with a useful method of initial symptom identification, diagnostic formulation, and serial assessment, as well as a means by which to resolve discrepancies between the history provided by the patient and his or her caregivers. Although the NRS-R was originally developed for use among persons with TBI specifically, in the authors’ experience this assessment is similarly useful among persons with ABI and DD more generally.

When patients are not able to participate directly in the provision of history, the initial assessment may be limited to observation of the patient supplemented by review of records and interview of a reliable informant on the patient’s neuropsychiatric status. In the authors’ experience, the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI)33 is a useful means by which to obtain neuropsychiatric symptom assessment in such circumstances. Originally developed for use among persons with dementias, the NPI assesses ten domains of psychopathology (i.e., delusions, hallucinations, agitation/aggression, dysphoria, anxiety, euphoria, apathy, disinhibition, irritability/lability, and aberrant motor behavior) commonly experienced by patients with many types of neurobehavioral disorders. A screening question for each domain is asked of the informant; this approach allows the clinician to identify potential areas of neuropsychiatric disturbance and to avoid potentially unrewarding avenues of inquiry. The NPI generally requires 10 to 20 minutes to complete, although interviews of caregivers unfamiliar with the distinctions between certain domains of neuropsychiatric dysfunction (i.e., depression vs. apathy, agitation/aggression vs. irritability/lability) may require explanations of these distinctions, thereby necessitating a longer initial interview. Educating caregivers provides them with a framework to monitor the patient’s behavior and improve future reporting.

After the initial administration, a questionnaire form of this instrument, the Neuropsychiatric Inventory-Questionnaire (NPI-Q),34 may be completed by the informant alone. A version of the NPI for use in institutional settings, the Neuropsychiatric Inventory-Nursing Home (NPI-NH),35 is also available; this version is predicated on clinician interview of staff members familiar with the patient’s neuropsychiatric functioning and adds two additional domains, nighttime behaviors and appetitive disturbances, to the assessment. Like the NRS-R, the NPI, in its several forms, provides the clinician with a useful method of initial symptom identification, diagnostic formulation, and serial assessment among patients with severe cognitive, behavioral, or communication impairments.

On the basis of data yielded by the NRS-R or the NPI, clinicians may further characterize the patient’s presenting problem with one or more symptom-specific scales (e.g., Hamilton Depression Rating Scale,36 Young Mania Rating Scale,37 Overt Aggression Scale,38 and Apathy Evaluation Scale,39 etc.). Because neuropsychiatric disturbances in persons with ABI and DD often cross conventional diagnostic boundaries or present in only partial forms,2,40 identifying symptoms requiring therapeutic intervention, rather than adhering strictly to a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR)-based41 categorical diagnoses, is often the most productive clinical approach.

Although not included in either the NRS-R or the NPI, screening for “spells” is also necessary. Epilepsy, particularly of the complex partial (with or without secondary generalization) type, is a common comorbidity among persons with DD42,43 and ABI44 and may be a cause of behavioral disturbances during or after seizures. Additionally, nonepileptic events, including pseudoseizures, are not uncommon in these populations.45,46 When the history identifies paroxysmal behavioral events, characterizing those events with respect to the presence or absence of other manifestations of seizures, and particularly the presence or absence of alteration in consciousness during or after the event, as well as event precipitants, potential behavioral reinforcers, and the effects of interventions (e.g., antiepileptic medications) is essential. Because many patients are unable to accurately report the character of their spells and subsequent behaviors, direct observation of their typical spells, sometimes using video-electroencephalographic monitoring, and obtaining descriptions from reliable informants is recommended before offering a diagnosis of either seizure or nonepileptic seizures. Identification of seizure-related behavioral disturbances will direct treatment toward epilepsy rather than its behavioral manifestations, thereby avoiding unnecessary psychopharmacologic interventions. Conversely, identification of nonepileptic events may permit the discontinuation of anticonvulsant medications and refocus treatment on the psychological and/or environmental precipitants as well as reinforcers of those events.

As a corollary to defining target symptoms, identifying not only what but also who requires treatment is essential. Although the medical convention is to regard the patient as the focus of treatment, the evaluation of neuropsychiatric problems among persons with ABI and DD cannot be decontextualized. The emotional or behavioral problems of the patient are better understood as a problemin the interaction between the patient and his environment.

Case Vignette

A 29-year-old, right-handed man with a remote severe TBI was referred by his insurance case manager for inpatient evaluation and pharmacologic treatment of “intractable aggression.” The preadmission history suggested daily, unpredictable aggressive behavior toward his wife and young children. Admission evaluation was remarkable for severe cognitive impairments, but agitation was noted only when the ward staff observed the patient’s wife speaking to him in a rapid, loud, and impatient manner and at a level of complexity inconsistent with his verbal communication skills. The raucous behavior of the patient’s young children increased his agitation. Staff intervention directed toward calming the wife and children, or escorting them out of the patient’s room, allowed resolution of the patient’s agitation.

These observations prompted education of the patient’s wife regarding the nature of his condition and the relationship between the family’s interactions with him and the patient’s unwanted behaviors. Despite extensive training of the patient’s wife, she was unable to modify her own behavior and her supervision of their children to meet the patient’s needs. He was discharged to a residential living center for persons with ABI where he had minimal agitation and staff there perceived no need for pharmacologic intervention.

This case is an example of a severe behavioral problem arising from the interaction between the patient and his environment. The evaluation yielded a clearer understanding of the antecedents of his agitation/aggression, allowed discharge to a setting in which the safety of the patient and his family was maintained, and obviated the need for pharmacotherapy of his agitated/aggressive behaviors. This example serves as a reminder to clinicians that proper treatment of the patient with ABI or DD necessitates assessment of both the patient and the context in which his or her neuropsychiatric disturbances arise.

REVIEW OF PRIOR INTERVENTIONS

In addition to the types of history taking and symptom identification described in the preceding text, pretreatment assessment of the patient with ABI or DD requires review of past and current treatments. A comprehensive assessment of pharmacologic, nonpharmacologic, prescribed, and self-administered treatments is encouraged, and should focus on three key issues: (a) the indications for such treatments; (b) the effects (positive, neutral, or negative) of those treatments; and (c) whether current symptoms reflect side effects of those treatments.

Consultation with other treating clinicians may be required to decide whether a current medicine is necessary or whether a new medicine might be helpful. When reviewing the indications for current treatments, avoiding the artificial distinction between “psychiatric” and “nonpsychiatric” medicines is recommended. By definition, patients with ABI and DD have an underlying neurologic condition. These neurologic conditions often require treatment in their own right (e.g., antiviral, anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, or antineoplastic agents) or produce other nonbehavioral problems (e.g., hemiparesis, spasticity, incontinence, etc.) that require treatment. Unfortunately, some agents used for these purposes may produce a wide range of problematic neuropsychiatric symptoms,47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52 including mood disorders, other affective disturbances, psychotic symptoms, and agitation, among others. Sometimes such treatments have not been properly applied, are predicated on misdiagnosis of the problem, or are the result of poor communication among treating professionals regarding the problem in question. Conversely, some medicines initiated for other conditions may have neuropsychiatric benefits and can play a role in the treatment plan. Examples include β-blockers started for hypertension that can reduce aggression and anticonvulsants given for seizures that can stabilize mood. Accordingly, identifying relationships between neuropsychiatric disturbances and treatments prescribed for the neurologic or medical conditions of persons with ABI and DD is an essential element of the pretreatment assessment.

Similarly, review of treatments directed at reduction of neuropsychiatric symptoms and unwanted behaviors is also required before undertaking additional therapeutic interventions of any kind. Although many medicines may alleviate neuropsychiatric disturbances among patients with ABI and DD, some agents may produce such problems. For example, paradoxical agitation, although an uncommon problem, may develop in response to treatment with benzodiazepines,53 valproate,54 or more rarely with cholinesterase inhibitors.55 Depression, psychosis, and other behavioral disturbances occur with some anticonvulsants.50,52,56 Lingering effects of previously prescribed treatments, and particularly antipsychotic-induced extrapyramidal syndromes such as tardive akathisia57, 58, 59 are also potential causes of behavioral disturbances among persons with ABI and DD. Where possible, eliminating or reducing potentially problematic medicines—particularly when a temporal relationship between treatment with such agents and problematic behaviors or psychiatric symptoms can be established—may alleviate such symptoms and thereby avoid prescription of additional agents.

In some cases, a potentially effective medicine or nonpharmacologic intervention has not been beneficial because it has been offered in a dose that is inadequate or for a period of time that is too brief. In such circumstances, undertaking an empiric trial of an intervention that was previously deemed “unhelpful” may be very useful. If a previous treatment was maximally employed but affected only a partial improvement in the symptom for which it was used, reinstituting that treatment and augmenting it with another, whether pharmacologic or behavioral/environmental, with a complementarymechanism of action may be helpful. This strategy may also help the clinician avoid serial empiric trials of several individually ineffective, or only partially effective, treatments.

COGNITIVE EXAMINATION

Cognitive impairments and related functional disabilities should be identified in persons with ABI and DD admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit. However, such information is often more usefully gathered from history than by formal assessment at the time of inpatient psychiatric admission.

As noted earlier, most administrative formulations of DD require intellectual impairment. The severity of impairment graded by age-appropriate full-scale IQ: 50 to 70 = mild, 35 to 50 = moderate, 20 to 35 = severe, and <20 = profound. Among patients admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit with a history of DD, information regarding the severity of intellectual disability will have been acquired at some point in the past. Obtaining that information may be a useful guide with which to formulate a treatment plan that is adjusted to the patient’s cognitive abilities and disabilities and that is communicated to the patient in a manner sensitive to his or her ability to understand it.

Among persons with ABI, cognitive impairments also are an expected part of the clinical presentation. The types and severities of impairments vary with the types and severities of ABI, although the correspondence between initial injury severity and long-term cognitive impairment is not strict.2 By the time a person with an ABI is admitted to an inpatient psychiatric setting, an assessment of post-ABI cognitive impairments and related functional disabilities often has been performed. When available, that information should be obtained before treatment initiation. Among patients with ABI, and particularly TBI, without prior assessments clinicians are advised to maintain a high level of suspicion for cognitive impairments of possible clinical significance and to undertake at least a preliminary cognitive assessment.

Psychiatric conditions of severity sufficient to necessitate inpatient hospitalization tend to impair performance on tests of cognitive ability. Accordingly, performing such assessments at the time of admission may overestimate the severity of cognitive impairments. When not understood in the context of, and perhaps at least in part as a product of, the psychiatric condition for which the patient was admitted, such testing may foster erroneous negative assumptions about the patient’s ability to participate in treatment planning, behavioral and other nonpharmacologic treatments, and disposition determinations.

This assessment should include evaluation of level of arousal, with vigilance for signs of either hypo- or hyperarousal; attention, including at least the ability to select and sustain focus to relevant environmental targets and freedom from attention to hallucinatory stimuli; speed of information processing; language, and particularly impairments in the ability to communicate suggestive of aphasia; memory, including the ability to retrieve previously learned information, the ability to learn and recall new information, and the ability to learn new procedures; praxis (the ability to perform previously learned skilled purposeful movements on command), including single-step and multistep sequences; recognition (gnosis) in visual, auditory, and tactile domains; visuospatial function, with particular vigilance for signs of hemi-inattention or neglect; and executive function (retrieval, sequencing and organization of information, conceptualization/abstraction, judgment, and insight).

For most patients, bedside cognitive “screening” measures, such as the Mini Mental State Examination,60 one of the various versions of the clock drawing test, the Frontal Assessment Battery61 and related executive function measures are usually sufficient for the purpose of identifying major domains of cognitive impairment that may affect the patient’s ability to participate in the development and execution of a treatment plan. When the patient is not able to participate in a structured cognitive assessment, an observational cognitive assessment anchored to the domains described in the preceding text should be performed.

When cognitive impairments are identified, it is essential that the clinician discuss these findings with reliable informants and/or review of medical records to confirm that such impairments are a known part of the patient’s preadmission history. If they appear to be new, then the clinician must determine whether they reflect the effects of the psychiatric illness on cognition (e.g., impaired attention due to hallucinations, memory and executive impairments due to depression, disorganized thought and behavior due to severe psychosis) or instead suggest a nonpsychiatric cause of cognitive impairment. Among the nonpsychiatric problems of greatest concern are medical conditions or intoxication/withdrawal states causing delirium and also acute neurologic processes producing focal neurobehavioral syndromes

(i.e., stroke-causing aphasia and apraxia, fall-producing bifrontal subdural hematomas and executive dysfunction, etc.). In either case, reevaluating apparent “psychiatric” symptoms as possible manifestations of an acute or subacute medical, substance-related, or neurologic condition and undertaking timely medical and neurologic evaluations (discussed in the subsequent text) is necessary.

(i.e., stroke-causing aphasia and apraxia, fall-producing bifrontal subdural hematomas and executive dysfunction, etc.). In either case, reevaluating apparent “psychiatric” symptoms as possible manifestations of an acute or subacute medical, substance-related, or neurologic condition and undertaking timely medical and neurologic evaluations (discussed in the subsequent text) is necessary.

If the cognitive impairments observed are felt to reflect the effects of the patient’s psychiatric illness or are stable sequelae of the patient’s ABI or DD, further evaluation of cognitive function specifically may not be necessary. Understanding the nature and severity of the patient’s cognitive impairment allows staff to adjust communication and behavioral expectations to the patient’s strengths and limitations. This information is also used to develop behavioral interventions for the neuropsychiatric problems that prompted psychiatric hospitalization.

PHYSICAL AND NEUROLOGIC EXAMINATIONS

Performing a thorough physical and neurologic examination before initiating treatment among persons with ABI or DD is highly recommended.62 Patients with ABI and DD may require more frequent explanation and reassurance about interview and examination procedures than might ordinarily be offered to patients with primary psychiatric disorders. Such explanations should be stated simply and succinctly and offered as frequently as needed to maintain the patient’s attention to the task at hand.

These examinations should include evaluation for signs of systemic disease (e.g., hypothyroidism and other endocrine disturbances, infectious or inflammatory disorders), substance abuse (e.g., physical hallmarks of alcohol or drug use), and impairments in elementary neurologic function. Identification of untreated physical or neurologic problems that, although not causes of neuropsychiatric problems per se, are potentially important comorbidities may alter treatment recommendations. For example, patients with neuropsychiatric disturbances after TBI frequently experience headaches and other types of pain (e.g., due to spasticity, traumatic neuropathies), which may exacerbate depression, anxiety, or agitation/aggression. If these comorbidities are left untreated, the response of the neuropsychiatric problem of concern to pharmacotherapies and other treatments may be limited. Additionally, untreated sensory (e.g., hearing, vision) problems may limit the effectiveness of psychotherapy and other behavioral interventions requiring verbal or written communication.

Similarly, although alcoholism and other substance use disorders appear to be less common among persons with DD than in the general population63 their identification is essential before instituting an inpatient psychiatric treatment plan. Such problems are more common among persons with many forms of ABI, and particularly TBI, and they adversely affect medical, neuropsychiatric, and psychosocial functioning.64 Given the potential for limited self-report of such problems among persons with DD and ABI, examination for the physical signs of alcohol and drug abuse may identify both important contributors to neuropsychiatric disturbances64,65 as well as comorbidities requiring specific intervention.

In some cases it may be necessary to initiate preliminary treatment of severely disruptive or aggressive behaviors in order to examine the patient.24 Among the initial treatment of greatest concern is the use of seclusion or restraint. Except under circumstances of imminent harm to the patient or staff, seclusion and restraint should be avoided if at all possible. Cognitively impaired patients often have difficulty understanding the rationale for the use of such measures and may escalate behaviorally when they are employed, thereby delaying further the interview and examinations needed to inform treatment.

LABORATORY ASSESSMENTS

Routine screening for laboratory abnormalities among persons hospitalized for psychiatric disturbances only rarely identifies previously unrecognized medical problems requiring intervention.66 Testing patients with ABI or DD may be more productive.62,66,67 In particular, assessment of serum glucose, creatinine and blood urea nitrogen, vitamin B12, folate and thyroid-stimulating hormone levels, urinalysis and urine toxicology, and, when appropriate, pregnancy testing and serum drug levels (e.g., anticonvulsants, tricyclic antidepressants [TCAs], and/or some antipsychotic medications) may be clinically informative. The selection of such laboratory assessments is best guided by identification of historical and/or physical examination findings that suggests a reason for their performance. However, in the ABI and DD populations clinical suspicion for occult medical problems (e.g., urinary tract

infection) should be high and the threshold for undertaking laboratory assessments low, especially when the ability to perform a thorough history or physical examination is limited.

infection) should be high and the threshold for undertaking laboratory assessments low, especially when the ability to perform a thorough history or physical examination is limited.

ELECTROENCEPHALOGRAPHY

Routine, or screening, electroencephalography (EEG) is not recommended. However, if the history suggests the possibility of previously unrecognized epilepsy or encephalopathy then EEG may be useful. Although a “negative” EEG does not exclude the possibility of epilepsy, interictal epileptiform discharges, severe diffuse or focal slowing, or other markedly abnormal EEG findings (e.g., periodic lateralized discharges, periodic sharp waves, triphasic waves, etc.) may indicate a need for additional evaluation of medical or neurologic problems requiring specific intervention.

NEUROIMAGING

When available, review of previously performed structural neuroimaging studies (computed tomography [CT] or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) may be informative. If such imaging is not available or has not previously been performed, it may be useful to obtain and review anatomic brain studies before instituting a definitive psychiatric treatment plan. In addition to offering information regarding the possible anatomic bases of the patient’s cognitive, emotional, or behavioral symptoms, the type of neuroimaging findings may inform the treatment approach.

Among persons with severe TBI, damage to the anterior and orbital frontal cortices as well as anterior temporal cortices is relatively common. Given the behaviorally inhibitory functions served by these areas, loss of cortex in these areas is commonly associated with disinhibited and/or aggressive behavior. In addition to suggesting a need for environmental interventions that decrease antecedents to such behaviors, neuroimaging findings of this sort suggest that pharmacologic interventions directed toward decreasing the limbic drive toward disinhibited or aggressive behavior (e.g., selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs], anticonvulsants, or atypical antipsychotics) may be more useful than those intended to augment the function of residual ventral anterior frontal and temporal cortices (e.g., psychostimulants, cholinesterase inhibitors).

Similarly, severe injury to dominant hemisphere lateral temporal and/or parietal cortex is associated with impairments in language comprehension (e.g., Wernicke or transcortical sensory aphasias) and, more occasionally, paranoid interpretation of the actions of others.68 Among patients with deficits in language comprehension, therapeutic interventions predicated on verbal reassurance, redirection, and/or limit setting are unlikely to succeed, and pharmacologic interventions intended to improve language function are similarly unlikely to be successful. Armed with knowledge of the anatomy and severity of the brain injury underlying the patient’s failure to respond to verbal cueing and to aphasia-targeted pharmacotherapy, the clinician will be better equipped to educate staff and caregivers about the nature of the patient’s condition and the need for nonverbal interventions.

By contrast, neuroimaging that demonstrates injury restricted to cerebral white matter with axonal sparing, or even no overt evidence of brain damage, suggests a higher likelihood of improving neurobehavioral function through pharmacologic and/or environmental interventions. In such circumstances, instituting treatments directed toward augmentation of cortical areas required to effect neurobehavioral improvement may be useful—particularly when the treatment suggested seems counterintuitive to other staff members (e.g., stimulants or other catecholaminergically active agents in the hyperactive and impulsive brain-injured patient69).

Case Vignette

A 55-year-old, right-handed man was admitted to a long-term inpatient psychiatric unit at a state hospital from a nursing home for intractable psychotic and aggressive symptoms.

The available history suggested onset of such problems approximately 30 years earlier, necessitating a series of unsuccessful inpatient psychiatric and nursing home placements spanning decades. The patient was unable (or “unwilling” according to staff members) to provide any historical information and was widely disliked by staff because of his apparent uncooperativeness with treatment (and particularly verbal redirection and limit setting). His verbal output, spontaneously or with prompting, was severely limited, generally consisting of single-word and frequently unintelligible utterances. The patient appeared to be responding to internal auditory stimuli, prompting a paranoid and aggressive behavior directed at anyone near him.

The available history suggested onset of such problems approximately 30 years earlier, necessitating a series of unsuccessful inpatient psychiatric and nursing home placements spanning decades. The patient was unable (or “unwilling” according to staff members) to provide any historical information and was widely disliked by staff because of his apparent uncooperativeness with treatment (and particularly verbal redirection and limit setting). His verbal output, spontaneously or with prompting, was severely limited, generally consisting of single-word and frequently unintelligible utterances. The patient appeared to be responding to internal auditory stimuli, prompting a paranoid and aggressive behavior directed at anyone near him.

A neuropsychiatric evaluation identified a comment in a record from a prior hospitalization suggesting that the patient had been in a motorcycle accident approximately 30 years previously. Neurologic examination identified bilateral mitgehen-type paratonia, a mild spastic catch on extension of the right upper extremity, right-sided hyperreflexia, Babinski and Hoffman signs, and multiple primitive reflexes. In light of a history suggesting a possible remote TBI and an abnormal neurologic examination, MRI of the brain was recommended.

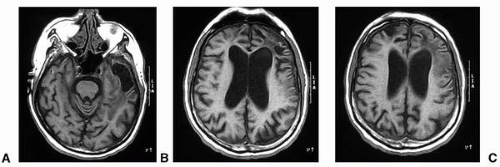

The MRI of the brain (see Fig. 17.1) identified a bilateral (left greater than right) anterior temporal porencephalic cysts, bilateral anterior frontal porencephalic cysts, bifrontal cortical atrophy, and severe bifrontal (left greater than right) white matter injury, consistent with a remote, severe TBI. This study suggested neuroanatomic bases for his impaired language function (left frontal and temporal damage), disinhibited and aggressive behavior (bilateral anterior and ventral frontal damage), and schizophreniform psychosis (severe left frontotemporal damage with bifrontal and bitemporal involvement70).

Communication of these findings to nursing staff allowed them to reframe his “unwillingness” to communicate verbally as an inability to do so because of nonfluent aphasia, to view his behaviors as products of his TBI rather than as intentional “uncooperativeness,” and to understand his psychosis as reflective of very severe TBI. Environmental interventions designed to eliminate the antecedents to his unwanted behaviors and to enhance nonverbal communication were then able to be implemented more successfully. Additionally, staff members had more reasonable expectations regarding the likelihood of response to treatment of his aggression and psychosis with anticonvulsants and antipsychotic medications.

Although functional imaging (single photon emission computed tomography [SPECT], positron emission tomography [PET], and functional magnetic resonance imaging [fMRI]) is increasingly available, its use in the inpatient psychiatric evaluation and treatment of persons with ABI and DD does not often add therapeutically useful information to the evaluation of such patients. Accordingly, the use of functional imaging is not recommended in this context.

Treatment of Neuropsychiatric Disturbances in Acquired Brain Injury and Developmental Disabilities

PSYCHOLOGICAL INTERVENTIONS

Psychological, behavioral, and environmental assessment and management is the cornerstone of treatment of patients with ABI and DD.71,72 In all cases, supportive counseling—even if directed only toward engagement in treatment73—is recommended. When patients are cognitively and linguistically capable of engaging in other forms of psychotherapy, including cognitive-behavioral therapy, dialectical behavioral therapy, interpersonal therapy, and group (including family) therapy, such therapies should be offered.74, 75, 76, 77, 78 Use of such interventions, particularly cognitive-behavioral therapies, improves coping skills among persons with ABI and DD.74,75 Cognitive-behavioral therapies also appear particularly useful for the treatment of depressive, anxious, and anger symptoms in these populations.79, 80, 81

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree