and Jeffrey R. Strawn2

(1)

Department of Psychiatry and Child Psychiatry, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio, USA

(2)

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio, USA

Abstract

Presenting case material to colleagues requires preparation, whether the presentation is to be made casually during bedside rounds or in the formal environment of a national meeting. It is rewarding when a presentation is well received, particularly because it may prove helpful to other clinicians, allied health professionals, and researchers. Regardless of the setting, the presenter’s goal is to share their knowledge based on observations they have made and lessons they have learned from the case or cases. The most time-consuming aspect of the patient-oriented presentation is collecting and organizing as much information as possible about the patients, their families, and others who were involved in the patients’ care. Once these tasks are complete, the presenter must summarize the information and place it within the context of treatment data and consensus approaches. Tailoring the talk to the audience is also of paramount importance. Different groups will invariably come from different disciplines, and the presentation will need to be tailored to accommodate each audience’s background, interests and goals.

Make everything as simple as possible, but not simpler

—Albert Einstein (1879–1955)

Presenting case material to colleagues requires preparation, whether the presentation is to be made casually during bedside rounds or in the formal environment of a national meeting. It is rewarding when a presentation is well received, particularly because it may prove helpful to other clinicians, allied health professionals, and researchers. Regardless of the setting, the presenter’s goal is to share their knowledge based on observations they have made and lessons they have learned from the case or cases. The most time-consuming aspect of the presentation is collecting and organizing as much information as possible about the patients, their families, and others who were involved in the patients’ care. Once these tasks are complete, the presenter must summarize the information and place it within the context of treatment data and consensus approaches. Tailoring the talk to the audience is also of paramount importance. Different groups will invariably come from different disciplines, and the presentation will need to be tailored to accommodate each audience’s background, interests and goals.

8.1 Presentations

There are a multitude of presentation formats for sharing and discussing clinical cases, diagnostic formulations or dilemmas, treatment approaches, and ethical issues. These presentation formats vary in terms of the number and type of participants, the use of multimedia , the availability of continuing medical education credits, etc. (Hull et al. 1989). Below, we describe the most common formats for clinical presentations and the challenges and unique features of each, though we recognize that aspects of these presentations will vary by organization, institution, and region.

Teaching Rounds Presentations

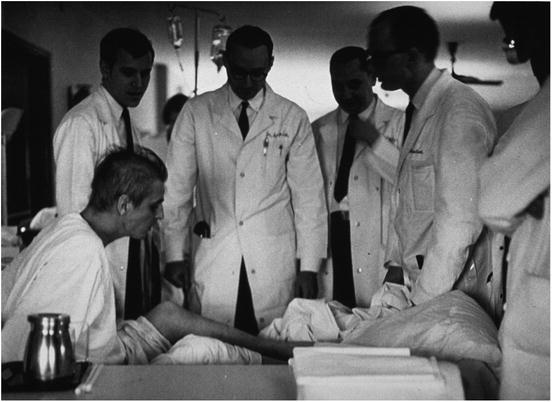

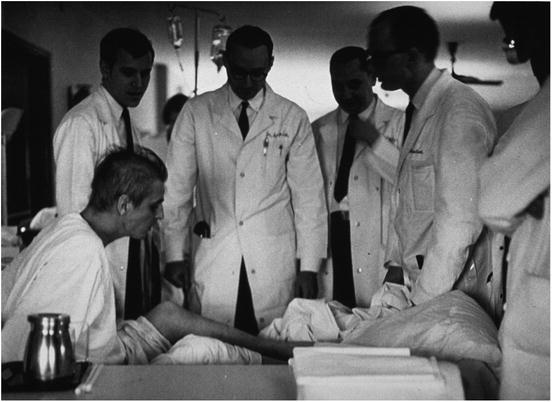

Teaching rounds have been the tradition in academic hospitals in which faculty members work closely with trainees, typically on a daily basis, so as to educate them about clinical approaches for patient care (Fig. 8.1). Faculty also use this model to teach trainee s to present cases with specific complex issues in a succinct, effective, and collegial manner. Generally, teaching rounds involve small groups of clinicians within a department and are usually scheduled daily to weekly, depending on the institution or department. Various members of the department may attend, including faculty, residents, interns, and nurses. In this context, the presenter can assume that most of those attending have a similar fund of knowledge regarding medical and psychiatric illnesses, and therefore the intent of the presentation is to highlight unique and unusual aspects of a particular patient, facilitating the discussion of new diagnostic, clinical, or treatment concepts. In these rounds, the presenter typically reviews the patient’s history and the course of his or her medical or psychiatric illness, as well as diagnostic formulations and best-practice treatment plans. The presenter may find it helpful to utilize the table-based approach, as we have done throughout this book, to systematically integrate aspects of temperament , cognition , defense mechanisms , family systems , and ethical issues.

Fig. 8.1

Bedside teaching rounds c. 1960 Photo by Roy Perry. National Library of Medicine

Clinical Case Conference Presentations

This type of conference permits clinicians to present material regarding complex cases and involves active discussion by participants about clinical formulations, diagnostic challenges, and/or best-practice treatment issues. A clinical case conference frequently utilizes an external discussant /moderator who approaches the case from one or two theoretical vantages. The discussant will also summarize the clinical material presented and may reformulate the material and expound on complex diagnostic or treatment issues. Importantly, the discussant is often charged with facilitating the discussion between the presenters and the audience members .

Grand Rounds Presentations

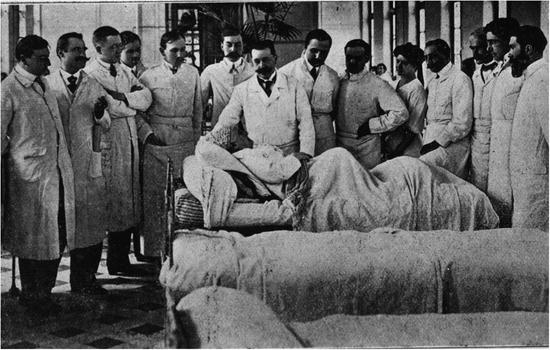

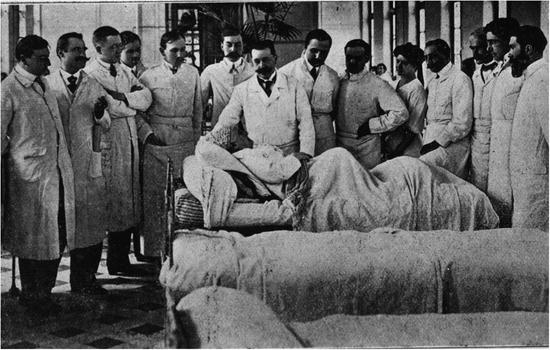

Historically, in teaching hospitals over the last century, “grand rounds ” consisted of a regular gathering of students , resident physicians, attending physicians, and senior physicians who observed as a junior and senior colleague examined a patient (Fig. 8.2), then engaged in a “Socratic dialogue, that often led the audience in a step-by-step deciphering of the ailment” (Altman 2006). Over the last several decades, grand rounds have taken the form of didactic lectures (Altman 2006) that focus on epidemiologic findings, pathophysiology and risk factors for a given condition, and treatment approaches that rely on evidence-based medicine (Sackett et al. 1996). Modern grand rounds may still include the review of a case history, which allows a senior presenter to share the popular “clinical pearls ” (Lorin et al. 2008). Despite its transformation over the recent years (from patient to participant focus), grand rounds remain a crucial element of medical education in, as Lawrence Altman, M.D. laments, “an era of proliferating subspecialties.” Altman also notes that grand rounds serve myriad purposes, in that it “emphasizes a core body of knowledge that all physicians need to share and to keep abreast of. And the meetings serve a social function. With coffee cups and bagels or pizza in hand, doctors mingle with colleagues before and after grand rounds. For some, it is the only time they see one another during the week” (2006).

Fig. 8.2

Dr. Jacob Gershberg presenting grand rounds at beside c. 1920. National Library of Medicine

The grand rounds presenter should keep in mind that audience members will have varying levels of training and experience and may have different theoretical orientations with different expectations about how the clinical material is understood. It is unrealistic to expect that an experienced and knowledgeable clinician will always be a good speaker, or that a good speaker will be able to please all members of the audience. Nonetheless, it is imperative to provide one’s clinical opinions with the best intentions, reminding the audience that the presentation is the synthesis of a great deal of information that the presenter believes is relevant, helpful, and current. It is important both to convey the material in a manner that is sensitive to the unique needs and perspectives of the audience (e.g., community-based physicians, subspecialty physicians, research faculty, advance practice nurses, psychologists, etc.) and to consider how the material will be viewed by the different disciplines present. The presenter should keep in mind the diverse audience and briefly highlight the reason the chosen case is significant. This should be followed by a succinct review of the elements that capture the complexities of the case and a discussion of what reasonable outcomes could have been anticipated, with caveats describing what may have interfered. When presenting to a non-mental health audience, one should understand the basic knowledge the audience has as well as their style in conceptualizing cases.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree