Introduction

Epilepsy imposes a significant clinical, epidemiologic, and economic burden on societies throughout the world. This chapter focuses on the economic dimension of this burden or impact, in particular how it can be measured and, ultimately, how it can be reduced. Three specific questions are addressed: First, what is the relevance of an economic perspective to the management of epilepsy as a public health issue? Second, what is the economic perspective on the burden of epilepsy, and how well do economic studies demonstrate this burden? Third, what is the economic perspective on evaluation, and how does economic evaluation contribute to the evidence on clinical and cost effectiveness? This chapter complements others in this volume that deal with related topics, including the issues surrounding epidemiologic burden and need, treatment effectiveness, and the costs of treatment.

Interest in the economic aspects of epilepsy has been growing in both richer and poorer countries. In the wealthier nations, an ongoing debate continues about how to curb rapidly rising health care costs. State-financed health care systems are facing the problem of an inflation of needs and, therefore, are forced to find ways to limit the expenditures for health care. On the other hand, poorer countries are facing the fact of a tremendous need for health care but inadequate economic resources. The uneven distribution of epilepsy care among countries, and sometimes within countries, does not correspond so much with real needs, but rather with underlying economic conditions. It is a well-known fact that approximately 80% of all health expenditures occur in established market economies, whereas the remaining 20% of financial resources is spent in the rest of the world, where approximately 90% of the people with epilepsy are living.21 Therefore, it is important to consider the economic aspects of ongoing efforts to improve the situation of people with epilepsy in all regions of the world.

The growing interest in this field has led to an increasing number of publications on economic aspects of epilepsy. Since the early 1990s, attempts have been made to apply general instruments of health care economics to the field of epilepsy care. The first studies mainly concentrated on the calculation of the cost of epilepsy. In a second phase, the economic studies investigated, in particular, selected aspects of the treatment of epilepsy, such as antiepileptic drugs or epilepsy surgery, including its cost-effectiveness.4,24 In correspondence with the World Health Organization (WHO), the perspective has been broadened once again to the global burden of disease21 and to the assessment of the performance of different health care systems.20,32 Furthermore, economic aspects have been included within the Global Campaign on Epilepsy, a joint initiative launched in 1997 by the International League Against Epilepsy, the International Bureau for Epilepsy, and the WHO to improve the situation of people with epilepsy worldwide.

The Rationale and Relevance of an Economic Perspective

Before considering different methods and results from economic analyses of epilepsy and its treatment, it is important to raise the question of why such studies are needed in the first place. In short, the requirement for an economic dimension in planning and evaluating treatments and services for epilepsy stems from a tension between, on the one hand, the epidemiologic or clinical need for intervention, and on the other, the resources available to meet this identified need. In the extreme case of there being no limits on resource availability, there would be little need for an economic dimension, other than to track the steady, unremitting flow of monies being channeled into epilepsy care and prevention. Equally, in the extreme case that care or prevention strategies are entirely ineffective or unavailable, economic considerations might be restricted to considering the economic consequences of the untreated natural history of disease. Of course, the reality for most diseases and most countries is that effective care and/or prevention strategies exist, but the budget is limited, which implies that choices must be made about which interventions to make available within this budget constraint. Assuming that the primary goal of a health system is to optimize potential health improvements in the population, then the choice is made mainly in terms of delivering maximum health gain for least cost. This is in fact a definition of efficiency, and is the concept underlying cost-effectiveness and other forms of economic evaluation (see later sections).

In addition, economic considerations may and certainly should enter into the debate around a number of other components of epilepsy care, including the organization or quality of primary care and neurologic services in a country, plus the financial protection of epilepsy patients and their families from potentially catastrophic payments for drugs and health care services. There is currently very little available epilepsy-specific evidence that can be drawn upon to shed light on these issues, but the experience from comparative international studies undertaken is that reliance on private, out-of-pocket payments by households for health care is a far less equitable financing mechanism than prepayment via taxation or insurance.34 In countries where there is a high level of out-of-pocket expenditures on health, therefore, an increased likelihood exists of pushing households containing a family member with epilepsy into impoverishment.

The Epidemiologic and Economic Burden of Epilepsy

The “burden” of epilepsy can be considered at a number of levels and from a number of different viewpoints, so it is as

well to distinguish between these different perspectives when thinking about what measured burden is likely to show. Most directly, this “burden” will be felt at the individual or household level in terms of the physical pain and psychological stress associated with epileptic seizures, the (potentially catastrophic) financial implications of treatment or lost work opportunities, and, in all too many societies, the social stigma attached to this condition. By contrast, burden at the community or population level is typically expressed in terms of the epidemiologic profile of the disease (numbers of new or existing cases in the population), the financial resources devoted to prevention and treatment, and societal productivity losses resulting from premature mortality or morbidity. The focus here is on population-level estimates of both the epidemiologic and economic burden attributable to epilepsy at the national and international level, but this should not detract from the importance of establishing and sharing better information concerning the household burden of epilepsy, particularly in low-income countries where the risk of catastrophic out-of-pocket expenditures is highest.

well to distinguish between these different perspectives when thinking about what measured burden is likely to show. Most directly, this “burden” will be felt at the individual or household level in terms of the physical pain and psychological stress associated with epileptic seizures, the (potentially catastrophic) financial implications of treatment or lost work opportunities, and, in all too many societies, the social stigma attached to this condition. By contrast, burden at the community or population level is typically expressed in terms of the epidemiologic profile of the disease (numbers of new or existing cases in the population), the financial resources devoted to prevention and treatment, and societal productivity losses resulting from premature mortality or morbidity. The focus here is on population-level estimates of both the epidemiologic and economic burden attributable to epilepsy at the national and international level, but this should not detract from the importance of establishing and sharing better information concerning the household burden of epilepsy, particularly in low-income countries where the risk of catastrophic out-of-pocket expenditures is highest.

Before illustrating the assessment of both the epidemiologic and economic burden of epilepsy, it is important to note that epilepsy is not an uniform disease, but rather a term that summarizes many conditions that have the symptom of an epileptic seizure in common. Policy-makers, such as governments or insurance agents, often do not distinguish between the different forms of epilepsy when evaluating the need for care and the services available, respectively. In economic terms, the consequences of having epilepsy may vary considerably depending on the frequency, severity, and kind of seizures. Furthermore, not all economic consequences may be attributable to epilepsy, because epilepsy is often related to an underlying disease that may continue to exist even after remission of the seizures. Various economic studies in epilepsy have therefore divided up the population with epilepsy into different prognostic groups with similar health care needs.2

Epidemiologic Assessment of the Global Burden of Epilepsy

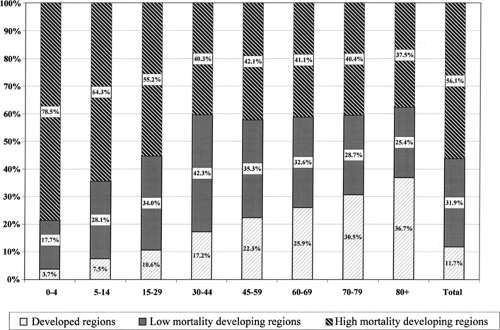

From the epidemiologic perspective, epilepsy is a significant cause of disability and disease burden in the world. Using a metric called the disability-adjusted life years or DALY,21 which can be thought of as 1 lost year of healthy life, the WHO has calculated the global burden of disease and injury attributable to different causes or risk factors. This measure of burden assesses the gap between current health status and an ideal situation in which everyone lives into old age free of disease and disability. Overall, epilepsy contributed more than 7 million disability-adjusted life years (0.5%) to the global burden of disease in 2000.15,33 FIGURE 1 shows the distribution of DALYs or lost years of healthy life attributable to epilepsy, both by age group and by level of economic development. It is apparent that close to 90% of the worldwide burden of epilepsy is to be found in developing regions, with more than half occurring in the 39% of global population living in countries with the highest levels of premature mortality (and lowest levels of income). An age gradient is also apparent, with the vast majority of epilepsy-related deaths and disability in childhood and adolescence occurring in developing regions, whereas later on in the lifecycle, the proportion drops because of relatively greater

survival rates into older age by people living in more economically developed regions. In terms of the absolute number of healthy life years lost per 1 million population, estimates range from less than 500 in early childhood and older age in developed regions to as much as 2,000 in the younger age groups of high-mortality developing regions. Owing to the consistent and comparative nature of this work, summary estimates of population health such as these provide the most appropriate measure of the relative burden of epilepsy at the international level.

survival rates into older age by people living in more economically developed regions. In terms of the absolute number of healthy life years lost per 1 million population, estimates range from less than 500 in early childhood and older age in developed regions to as much as 2,000 in the younger age groups of high-mortality developing regions. Owing to the consistent and comparative nature of this work, summary estimates of population health such as these provide the most appropriate measure of the relative burden of epilepsy at the international level.

That is not to say, however, that such summary measures of population health are not without limitations. For example, good-quality data on basic epidemiologic parameters (such as rates of incidence or recovery) do not exist for many developing countries, such that estimates for whole subregions of the world may be extrapolated from neighboring regions where such data do exist. Just as importantly, and in common with other disease categories, good-quality descriptive data on disability due to epilepsy were lacking at the time of this study. Recent work on the measurement of health state preferences in epilepsy14 suggests that the disability weights applied to treated and untreated epilepsy in the Global Burden of Disease study may be underestimated. Finally, DALY estimates of the burden of epilepsy take into account neither the potential health consequences on people other than the diagnosed case (such as the burden on family members or caregivers), nor the nonhealth consequences of disease (such as lost ability to work).

Economic Assessment of the National Burden of Epilepsy

Disease burden has also been gauged from an economic perspective for many years in the form of so-called “cost of illness” studies, which have attempted to attach monetary values—as opposed to DALY estimates—to a variety of societal costs associated with a particular disorder, often expressed as an annual estimate aggregated across all involved agencies. Such studies have direct parallels with epidemiologic estimates of disease burden, in the sense that the principal aim is to influence policy-making and resource allocation by demonstrating the relative magnitude or burden associated with a particular disorder (by multiplying case prevalence by cost per case, put very crudely). The potential advantage of cost of illness studies over DALY-based estimates of burden is that they are able to measure in a single metric (money) not only the direct health-related impact of disease (in terms of health care costs, etc.) but also other economic consequences such as lost work or leisure time, and family or caregiver burden.

Economic assessments of the national burden of epilepsy have been conducted in a number of high-income countries such as Italy and the United States1,3 and also in two developing countries, India and Burundi.22,29 A number of comparative reviews have also been produced.2,12,16,25 Each of these studies or reviews have set out to demonstrate the various economic implications the disorder has in terms of health care service needs and lost work productivity. For example, the Indian study calculated that the total cost per case of these disease consequences for epilepsy amounted to US$344 per year (equivalent to 88% of average income per capita), and that the total cost for the estimated 5 million cases resident in India was equivalent to 0.5% of the gross national product.29

An extensive array of costs is associated with epilepsy, including so-called “direct” intervention costs such as inpatient and outpatient care, medication, and diagnostic tests, and also “indirect” costs that cover lost time and productivity. The indirect cost of epilepsy, due to unemployment, underemployment, or premature death, is higher than one may assume. Studies have shown, for example, that in Europe, the unemployment rate among people with epilepsy is two or three times higher than among the general population.9 To face unemployment or underemployment is a severe problem for these patients. At the same time, it is an (often underestimated) economic burden to society.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree