A prior neurologic insult, indicated by features such as neurologic deficits from birth (intellectual disability and cerebral palsy) or history of traumatic brain injury (TBI) or other brain injuries leading to a static lesion, is the most powerful and consistent predictor of recurrence after a first seizure (3). Other factors include an epileptiform EEG abnormality, the occurrence of previous acute symptomatic seizures, nocturnal occurrence of the seizure, and a Todd paralysis (3,6). Status epilepticus (SE), focal seizures, and a family history of epilepsy have also been identified in some but not all studies.

The risk of subsequent seizures decreases with time, with up to 80% of recurrences occurring within 2 years of the initial seizure; recurrence rates are 36% in prospective studies and 47% in retrospective studies at 2 years (7). In the National General Practice Study of Epilepsy (NGPSE) conducted in the United Kingdom, 67% of those with a single seizure had a recurrence within 12 months and 78% within 36 months (8).

There remains debate regarding the similarities between acute symptomatic seizures associated with acute brain insults and unprovoked seizures. There are many differences in terms of subsequent morbidity and mortality, and the difference in seizure recurrence among those with unprovoked seizures and individuals with a first acute symptomatic seizure is also striking. People with an acute symptomatic seizure are 80% less likely to experience a subsequent unprovoked seizure than are individuals with a first unprovoked seizure. An MRI is appropriate in the evaluation of a first presumably unprovoked seizure, but the usefulness in predicting seizure recurrence is uncertain.

In two randomized clinical trials, use of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) in doses to maintain serum levels in the therapeutic range was associated with a reduction in the proportion of patients who experienced seizure recurrence after a first seizure (9,10). There was no benefit in terms of long-term prognosis for seizure freedom. In a prognostic model that was based on the Medical Research Council’s (MRC) “Multi-center trial for Early Epilepsy and Single Seizures (MESS)” data, the estimated probability of a second seizure at 1, 3, and 5 years for individuals treated immediately following a first seizure was 26%, 35%, and 39%, respectively. In this study, no significant difference was observed between the immediate treatment group and delayed treatment group with respect to being seizure free between 3 and 5 years after randomization, quality of life outcomes, and serious complications (11). In summary, drug initiation after a first seizure decreases early seizure recurrence but does not affect the long-term prognosis in terms of remission.

PROGNOSIS AT THE TIME OF DIAGNOSIS OF EPILEPSY

The entire natural history is modified when a diagnosis of epilepsy (recurrent unprovoked seizures) is made. Unlike the relatively low risk of a second seizure after a first unprovoked seizure (on average 40%), the risk for subsequent seizures following a second unprovoked seizure is closer to 100%, which moves the cost–benefit toward medical treatment and preparation for a much longer period for lifestyle modification. Predictors that the initial response to antiepileptic medication may be poor include multiple seizure types, a high number and density of seizures prior to treatment, and history of depression.

Initial response to treatment also provides clues to long-term prognosis. About half of newly diagnosed persons with epilepsy will obtain complete seizure control with the first antiepileptic medication, often at low doses. If failure of the first medication is related to side effects, the likelihood of control with a second medication is again excellent. However, if the failure is related to apparent ineffectiveness of the first medication, the likelihood of control with a second medication is considerably lower. Overall, about two-thirds of newly diagnosed persons with epilepsy will obtain control of seizures by either a first or a second medication. After that, changing therapy will provide control of seizures in only an additional 3% to 5% of people (12). As a corollary, the number of seizures after initiation of treatment can predict the long-term course.

It should be pointed out that failure to respond to two medications, the criteria set by the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) for “drug-resistant epilepsy” (13), is not tied to number of seizures or seizure density. One may have a seizure once a year or less and still qualify as “drug resistant” by this definition.

PROGNOSIS OF ESTABLISHED EPILEPSY

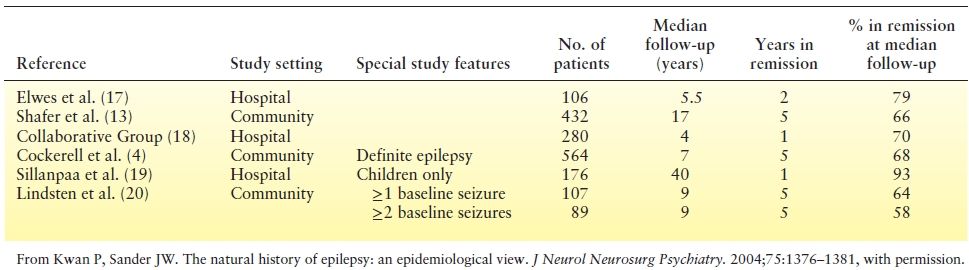

A community-based study of the natural history of treated epilepsy performed in Rochester, Minnesota, reported that the probability of attaining “terminal remission” (seizure free for 5 years) at 20 years after diagnosis was 75% (14). More importantly, almost 50% of the persons with epilepsy in this community-based study had entered remission at 6 years of follow-up following initial diagnosis of epilepsy, the earliest point they could be considered to be in remission. Similar data have been provided from the NGPSE. In that study, 60% of people with newly diagnosed epilepsy achieved a 5-year remission by 9 years of follow-up (15). Studies of newly diagnosed patients followed for long periods also tend to suggest a remission rate of 60% to 90% (16) (Table 2.2).

Table 2.2 Terminal Remission Data from Selected Studies

PREDICTORS OF REMISSION IN PERSONS WITH EPILEPSY

Many studies have looked at potential predictors of seizure prognosis, including age of onset, gender, etiology, seizure type, EEG patterns, number of seizures prior to treatment, and early response to treatment (21). A diagnosis of remote symptomatic etiology, or the presence of a neurologic deficit prior to the onset of the epilepsy, has consistently been shown to be associated with a poor prognosis (19).

The number of seizures and seizure patterns in the first 6 months or first year after diagnosis has been found to be a strong determinant of the probability of subsequent remission, with 95% of those with two seizures in the first 6 months achieving a 5-year remission compared with only 24% of those with more than 10 seizures during this same time period (22). Children who experience clusters of seizures during treatment are less likely to achieve 5-year terminal remission (23). Children who continue to have weekly seizures during the first year of treatment had an eightfold increase in the risk of developing intractable epilepsy and a twofold increase in the risk of never achieving 1-year terminal remission (18).

Seizure type has not been a consistent prognostic factor (14), although persons with multiple seizure types, as is typical in the catastrophic epilepsies of childhood, have a poorer prognosis (24).

MEDICATION WITHDRAWAL IN PERSONS WITH SEIZURE REMISSION

The most comprehensive study to evaluate the success of medication withdrawal was the MRC’s randomized Antiepileptic Drug Withdrawal Study. In this study, people who had been seizure free for at least 2 years were randomized to either slow withdrawal of medication or continued therapy. In the withdrawal group, 40% experienced seizure recurrence in the subsequent 2 years. The highest rate of recurrence was in the first year after the withdrawal was started. In the group continuing treatment, 25% experienced seizure recurrence by 2 years. The relapse rate was similar in the two groups after 2 years (25). The results suggest that people who need antiepileptic medication declare themselves early in the withdrawal period. The recurrence in those continuing therapy suggests that a relapse cannot be attributed solely to medication withdrawal. Even though a substantial proportion of patients in the MRC study remained seizure free after medication withdrawal, there were no powerful predictors that allowed for the identification of these individuals. In a multivariable analysis, factors that increased recurrence risk included history of focal seizures, myoclonic seizures, and tonic–clonic seizures (primary or secondary) as well as seizures after therapy initiation. In contrast, being seizure free for over 3 years at the time of randomization decreased the risk (25).

There seemed to be little impact on quality of life associated with withdrawal, although a seizure recurrence was associated with decline in perceived quality of life. Another study of randomized withdrawal demonstrated substantial improvement in cognitive function in those for whom medication was withdrawn (26).

PROGNOSIS OF UNTREATED EPILEPSY

Although some attribute a relatively favorable prognosis to early institution of antiepileptic medication therapy, evidence from studies from resource-poor countries with significant treatment gap suggests that many patients may enter spontaneous remission with no AED treatment. In northern Ecuador, 49% of 643 patients who had never received an AED were seizure free for at least 12 months (27). A study in rural Bolivia reported that 43.7% of untreated epilepsy cases were seizure free for more than 5 years when the cohort was revisited after 10 years (28

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree