The Neurogenic Bladder

Michael Ronthal

▪ INTRODUCTION

The first order of business in diagnosing bladder symptoms is to make the distinction between urological and neurological pathophysiology. Local pathology such as outlet obstruction or stress incontinence must be excluded before the neurological dysfunction is defined. At times the symptoms can be the same or similar; urgency and frequency could be due to cystitis rather than central nervous system (CNS) dysfunction, and retention could be due to bladder outlet obstruction or, say, cauda dysfunction. The urine must be examined in conjunction with the physical examination.

This chapter will deal, for the most part, with the neurogenic bladder and will begin with the “ground rules” for diagnosis, followed by a review of the physiology and pathophysiology of micturition.

▪ HISTORY

Enquiry should be made as to bladder sensation, frequency of micturition, nocturia, hesitancy, intermittency, pain, and dysuria as part of the general medical and neurological history. Overt blood in the urine clearly implies a urological problem. A review of the patient’s medication is mandatory. The presence of a gait disorder of any magnitude is strongly suggestive of a neurogenic basis for the symptoms.

Normal bladder sensation progresses in a continuum of gradually increasing intensity and unpleasantness from the first sensation of bladder filling, through the first desire to void, to a strong desire to void.

Urinary incontinence is defined by the International Continence Society as an involuntary loss of urine that is objectively shown and a social hygiene problem. Incontinence is present in 20% of women over the age of 40.

Urgency, which is an abnormal symptom, is either present or absent without a graduated increase in symptomatology and is defined as “the complaint of a sudden compelling desire to pass urine which is difficult to defer.” If there is involuntary loss of urine in the setting of urgency, urgency incontinence is suggested and implies detrusor hyperactivity. Loss of urine when coughing or straining suggests nonneurologic stress incontinence.

Micturition in a healthy adult with a bladder capacity of about 500 mL is likely to be approximately once every 3 to 4 hours; the physiological rate of bladder filling is about 2 mL per minute. Many normal individuals will have at most one episode of nocturia, and most usually have none.

Hesitancy and intermittency usually imply outlet obstruction, but hesitancy can be the symptom of detrusor/sphincter dyssynergy—the fundus of the bladder contracts on a closed sphincter.

Micturition should be painless, perhaps even slightly pleasant!

Any medication with anticholinergic effects can cause outlet symptoms, particularly in men. These include the tricyclic antidepressants and many of the neuroleptic agents, muscle relaxants, and sympathomimetics.

▪ EXAMINATION

Because bladder symptoms can be part of pathology at multiple sites in the nervous system, a detailed neurological examination must be performed. The mental status screen helps to diagnose frontal lobe disorders; parkinsonism is manifest by slowness; posterior fossa pathology by ataxia and cranial nerve signs; myelopathy by spastic, weak legs or loss of position sense; and cauda equina pathology by loss of ankle reflexes, saddle sensory loss, and poor sphincter tone. Finally, the bladder may be involved in autonomic neuropathy and postural hypotension, or lack of sweating may be the clues.

▪ DIAGNOSIS

The physiology of bladder function is complex and diagnosis can be difficult at the bedside, but some general principles are helpful. In general, central pathology can be likened to the upper motor neuron syndrome with spasticity—translated to the bladder this means a low-capacity, high-pressure system manifested by urgency, frequency, and urgency incontinence. This has been called detrusor overactivity or overactive bladder syndrome (International Continence Society). The syndrome could be idiopathic, but only by exclusion.

Lack of bladder sensation leads to a large, flabby bladder, with overflow incontinence sometimes labeled a “tabetic bladder.” The cause may be autonomic neuropathy, dorsal root ganglionopathy, or myelopathy. Acute cauda equina syndromes such as those caused by herpes simplex or massive disc herniation cause retention with or without sensory loss.

Acute spinal cord injury causes retention until an “automatic bladder” establishes itself by activation of suppressed or dormant C-fiber reflexes.

If bladder dysfunction occurs in the setting of spinal cord or cauda syndromes, whatever the pathology, a sense of urgency is injected into the management, which becomes an emergency. Many of the long-term complications of paraplegia are urological, and if treated early, might be avoided.

▪ INVESTIGATION

If a clearly defined site of pathology is suggested after the initial clinical examination, imaging studies should be performed and the cerebrospinal fluid should be examined if the imaging is negative.

If the site of pathology or the symptoms are unclear, further urodynamic studies will help to define the problem; however, urodynamics give information only as to bladder function and not etiology. The urodynamic evaluation may guide further neurological workup.

▪ BLADDER PHYSIOLOGY

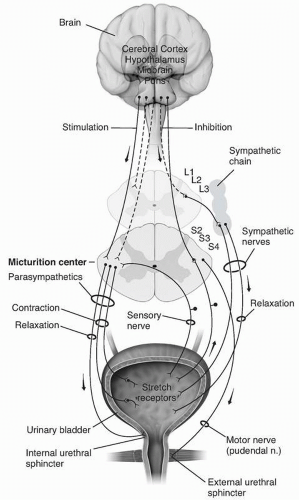

The functions of the bladder are only two—storage and emptying. The system is in storage mode for more than 99% of the time. As in all neurological functions there are both central and peripheral components that work synergistically to support normal bladder dynamics (Fig. 5.1).

Central Control

Suprapontine Centers

The highest center for motor control is cortex, more specifically the frontal cortex. In humans, positron emission tomography shows activation of the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex during micturition. The right anterior cingulate shows decreased blood flow when the subject is not able to micturate despite a full bladder.

The physiological purpose of normal bladder sensation is to provide information to the brain about bladder filling so that the voiding reflex can be kept under voluntary control. One should be able to decide when and where to void. Bladder sensation as investigated by activation magnetic resonance imaging shows activity in the insula bilaterally for normal bladder filling sensations, shifting anteriorly as the sensation becomes stronger and more unpleasant. Activity is also seen in the basal ganglia, periaqueductal gray (PAG), and anterior cingulate.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree