THE OUTCOME OF LATE-LIFE DEPRESSION

Around the turn of the nineteenth century Kraepelin changed the face of contemporary psychiatry, primarily by systematically following up his patients after treatment. The outcome or natural history of a disorder is, since that time, decisive for any appreciation of its clinical relevance, treatment or classification, and is a cornerstone of its conceptualization. In some disorders, such as dementia, the rate of progression of the illness may vary, but the eventual outcome is fixed. Other diseases, such as diabetes or osteoarthritis, may have an extremely varied course and prognosis, but are chronic by nature. The eventual outcome of both diabetes and osteoarthritis is by no means fixed. In both disorders the outcome can vary from being a disorder that, although causing considerable discomfort, remains under control, to a debilitating and pernicious disorder. The outcome of depression is even more varied than that. Some patients suffer one episode in life, recover fully, never to run into affective trouble again. For others depression is a severe and chronic disease, omnipresent in all spheres and phases of life and dyscolouring all life’s experience. The eventual outcome may vary from the depression having had a minor impact on the patient’s life, to suicide. Between these extremes, every type of course and outcome of depression exists. This holds for depression at all ages. Indeed, it may well be that, given the changes that occur in later life, the variability of the outcome of geriatric depression is even more pronounced than in earlier stages of life.

Given the extreme variability of the outcome of depression and the obvious importance this has for our patients, it is surprising how poorly both our theories and our classification of the prognosis of depression have developed. Although a good many studies have been conducted to assess the naturalistic outcome of depression at all ages, this has not led to a well-developed prognostic theory for affective disorders. The primary aim of treatment is to influence the prognosis and outcome of a disorder. Although hundreds of trials have been conducted to test the efficacy of treatments for depression, this also has not led to an integrated theory of the prognosis of affective disorders. The result is that classification has remained where it essentially has been since Kraepelin’s time: a purely descriptive system, categorizing what goes on while it goes on.

This chapter contains a reflection of this still rather primitive state of affairs. The first paragraph will discuss essential conceptual issues, relevant to the outcome of late-life depression. Thereafter, we will summarize the available data with regard to the naturalistic outcome of depression in older people. As will become evident, the pioneering studies in this area were conducted from specialized clinical centres, following up patients after discharge from clinical treatment. Later on, larger cohort studies were put together, following patients seen in general practice and in the community. These data will be used to test the hypothesis that the prognosis is generally more favourable in the community as compared with patients referred to specialized treatment centres. A second question is whether the prognosis of depression changes with age. To this end, results of studies conducted among older people will be compared with those in younger adults. Where possible, associations between age and the prognosis will be summarized. One of the myth’s surrounding age and ageing is that later life would be an age of melancholy. This myth has been falsified many times. Although some studies do show that the prevalence of depressive symptoms increases with age, this is related to age- related risk factors and not to ageing itself. The same question will be addressed with regard to the prognosis of late-life depression. Is there an effect of age? If so, is this a result of the ageing itself, or a change in age-related prognostic factors?

A related issue is whether the variation in outcomes of depression is increased in later life. If so, the potential benefit of being able to predict the individual prognosis early on in treatment is similarly increased. First episodes of depression may arise at all ages and there are subtypes of depression that generally arise only in later life (such as vascular depression or depression associated with neurodegenerative disease). It is therefore likely that the prognosis becomes more heterogeneous in later life and that there are specific aetio- logical or prognostic subtypes that are especially relevant to older people. Identifying prognostic factors is therefore a further aim of this chapter.

Co-morbidity is the hallmark of geriatric medicine. Studying disorders in isolation in older people is only rarely helpful or informative. This is especially true for late-life depression. Moreover, for our patients and in terms of public health, more functional and generic outcomes such as well-being, daily functioning and social integration are essential. As these generic outcomes are the product of all the co-morbid disorders the patient has to cope with, the final aim of this chapter is to consider the role the prognosis of depression plays in the overall well-being and functioning of older people.

There are many ways to define and measure the outcome of depression. As is the case in most areas of medicine, the methods employed have evolved from studies retrospectively and rather loosely classifying each patient in predefined clinical criteria, to prospective studies, rigorously measuring symptom severity at multiple time points. By definition, the more often symptoms are measured, the more likely it is that change will be detected. That would mean that the more recent and sophisticated studies, employing multiple measures over longer periods of time, are less likely to find a patient in sustained recovery and also less likely to conclude that the patient is chronically depressed.

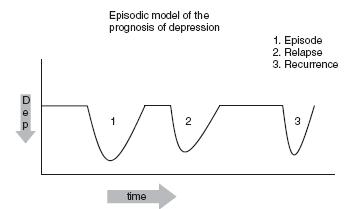

The way the outcome of a disorder is conceptualized has great impact on the way it is studied and treated. Frank et al.1 described clear criteria for what may be called the episodic model of the outcome of depression. This model, which is summarized briefly in Figure 80.1 has been by far the most influential. Depression is modelled as an episodic disorder, with a clear beginning, symptomatic stage and resolution phase. If, very soon after the symptoms have resolved, the patient suffers a relapse, this is considered part of the illness episode. If the recovery is more sustained and the patient suffers a recurrence, this is then considered to be a new episode. This well-known model has many merits. First, it is an optimistic model. Regardless of age, most patients recover and treatment generally helps to speed up recovery. The episodic model has also been helpful in both organizing our thinking about the prognosis of depression and in designing studies of treatment.

However, longer term follow-up studies employing multiple measurements have shown that patients often do not follow the neat stages of development of the disorder depicted in Figure 80.12. The best known example is the Collaborative Depression Study, in which more than 400 patients were followed up using detailed weekly life charts. Over 12 years of follow-up, it appeared that patients moved in and out of different levels of symptom severity and diagnostic subtypes; the symptoms often waxing and waning2. Using an episodic model of outcome it was reported that 70% of the patients had recovered after one year and that the mean duration of episodes was approximately six months3. Given the fact that these were patients referred (and motivated) for treatment in a tertiary treatment centre, the outcome was quite optimistic. However, after 12 years of follow-up, using life charts it appeared that these patients spent almost 60% of the time in a state with clinically relevant levels of depressive symptoms, severe enough to disturb both well-being and functioning2. The results have prompted the authors to conclude that the prognosis in depression is pleiomorphic instead of episodic2. When accommodating the pleiomorphic model in research, the prognosis of depression appeared less favourable than when adopting an episodic viewpoint. In practice, there are patients in whom depression follows the path of a clearly delineated episode, there are patients in whom the symptoms wax and wane over time and there are patients with a chronic course. This has clinical relevance, as the way treatment and follow-up are organized should be determined by the expected prognosis. Indeed, as was suggested by McCullough, there is good reason to consider more chronic forms of depression as a different disorder from the more benign episodic disorders4.

When describing the outcome of late-life depression in the next section, both the parameters relevant to an episodic view of outcome (such as the duration of an episode, the percentage of patients remitting within a given time, relapse or recurrence) and those relevant for a pleiomorphic viewpoint (the average symptom severity over time, the percentage of time patients spend in a depressive state) will be discussed.

THE PROGNOSIS OF LATE-LIFE DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMATOLOGY

Several systematic reviews have recently summarized the prognosis of late-life depression5-7. As was mentioned, the earlier studies were conducted as follow-up assessments of patients treated in clinical facilities. Over 20 such studies have been conducted. The outcome was often determined retrospectively in rather loosely defined clinical terms, such as the patient being well, recovery with relapses or being continually ill. Given various methodological shortcomings, Cole et al.5 concluded that the majority of patients (about 60%) were well or had suffered relapses with recovery, while 14-22% were continually ill. Both Cole et al.5 and Licht-Strunk et al.6 in a more recent review have found poorer outcomes when studying depressed patients recruited from the community or primary care. Licht-Strunk et al.6 summarized the findings of 4 primary care and 17 community-based studies that fulfilled quite rigorous methodological criteria. After a period of one year, 50-75% of patients no longer fulfilled diagnostic criteria for major depression. Taking a longer time-perspective, the available studies would suggest a rule of thirds: about one in three patients has a short-term remission, another one in three develops a chronic course, while the remaining third has a more varied prognosis, with intermittent episodes6. Only one study estimated the duration of episodes of major depression among older primary care patients. In a three-year follow-up of 234 older (55+) primary care patients with well-defined major depressive disorder, the average duration of an episode was estimated to be 18 months7.

Moving from clinically defined outcomes to the more abstract pleiomorphic measures the prognosis looks even worse. In the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam (LASA), which is a community- based study, 277 older depressed people were followed with six- monthly assessments over six years8. It appeared that almost half the sample was depressed more than 60% of the time over six years. Only one in three had a true chronic course, but another third of the patients were depressed most of the six years they were followed up, the symptoms waxing and waning over time.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree