The Role of European Regulatory Agencies

Michel Baulac

Eric Abadie

Introduction

Since 1989, eleven new antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) have been approved in the EU countries for epileptic disorders as indication. The regulatory work also included the evaluation of new dosages and routes of administration, as well as new indications when a drug initially approved for a given seizure type or epileptic condition was subsequently approved for additional seizure types or populations. In parallel, the EU pharmaceutical legislative framework was progressively implemented. The European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products (EMEA) was established in 1995 to coordinate and harmonize the processing of EU licence applications. The Committee for Human Medicinal Products (CHMP) is the advisory committee to the EMEA for medicines for human use, and comprises two delegates from each EU member state.

The national competent authorities or drug agencies from the member states are the scientific pillars of the EMEA. The EMEA’s guidance and recommendations are conveyed through an ensemble of guidelines. The EMEA position concerning AEDs is included in a specific scientific note for guidance, but it also derives from the experience acquired through the scientific advice provided and the EU procedures that involved recent applications for registration of new AEDs.

Overview of the Licensing Process in EU Countries

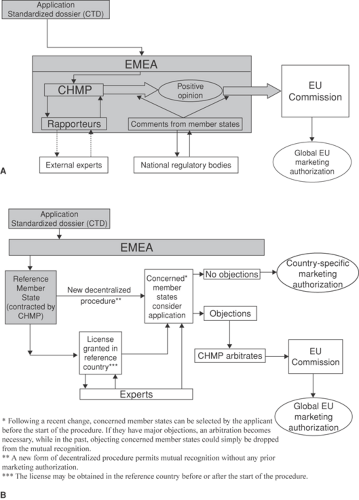

There are three routes by which a drug may be granted a product licence in the European Union. The centralized procedure, by which the company is authorized to release the drug in the market in any EU country, and the mutual recognition procedure, and a decentralized procedure. Some details of these procedures are shown in FIGURE 1. The national procedures, which involve the regulatory agencies in each individual member state, are critical in the mutual recognition system. The latter procedures also continue to be used when a drug initially approved through a national procedure, mostly before 1995, is subsequently considered for extension of its indications within the same country.

Once a product receives a marketing authorization from the EMEA, the company can approach individual governments to have it introduced in the relevant national markets. However, a company may decide not to launch in a particular country for commercial reasons. It is at this stage that other factors come into play, including the evaluation of the drug’s added value by the national health systems and pricing negotiations, which can significantly delay the actual marketing process.

The AEDs recently marketed in EU countries have followed different routes. Vigabatrin, lamotrigine, gabapentin, felbamate, and topiramate were marketed through national procedures, which were initiated before 1995. Every variation or extension of their indications continues to be dealt with by the individual national regulatory bodies, which explains some variability across EU countries regarding the wording of the indication, the dosage recommendations, or the age range, especially in the pediatric indications. Tiagabine, in 1996, was the first AED whose license application followed an EU procedure—the mutual recognition procedure. The EU approval of oxcarbazepine was also obtained through mutual recognition in 2000, given the fact that some EU countries had already individually approved this drug in the early 1990s. Levetiracetam (2000), pregabalin (2004), and zonisamide (2005) gained their EU approval through the centralized procedure. In addition, rufinamide was approved in 2006 for the adjunctive treatment of the Lennox-Gastaut syndrome seizures through Orphan Drug application.

EMEA Guidance and Recommendations

Within the framework of the pharmaceutical legislation, EMEA guidelines do not have legal force in that the definitive legal requirements are those outlined in the relevant EU legislative framework as well as appropriate national rules. However, guidelines are to be considered as a harmonized EU position and, when followed by relevant parties such as the applicants, companies, and regulators, will facilitate assessment, approval, and control of medicinal products in the European Union. Nevertheless, alternative approaches may be taken, provided that these are appropriately justified.

Scientific guidelines (or notes for guidance), including those related to quality, efficacy, and safety, are based on the most up-to-date scientific knowledge. A guideline is normally developed in accordance with the following steps:15 (a) selection of topic and inclusion in the relevant work program(s); (b) appointment of a rapporteur and (if necessary) a corapporteur; (c) development of a concept paper and release for consultation; (d) preparation of the initial draft guideline; (e) release for consultation of the draft guideline and collection of comments; and (f) preparation of the final version, adoption for publication, and implementation.

The need for a new guideline may be made evident by frequently encountered problems with established products or by questions brought forward within the framework of scientific advice. A need for a guideline may also arise due to the development of new technologies, new practices, or new therapeutic areas. Inputs for developing or revising guidelines may also be received from interested parties (e.g., industry, health professional groups, scientific societies, patients’ associations, etc.). Guidelines can also be initiated and drafted by the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH).

The rapporteur for the development of a guideline is a member of the CHMP Efficacy Working Party who works on the

draft with experts of his or her choice. After release for consultation, comments are expected from EU/EEA/EFTA countries, other regulatory authorities (e.g., the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Health Canada), industry associations, scientific and academic societies, patients’ groups, and health care professionals. Unless otherwise indicated, guidelines come into operation 6 months after their adoption. The current EMEA guideline on AEDs11 was drafted from April 1998 to September 1999, commented on from October 1999 to April 2000, and adopted in November 2000, and it came into operation in May 2001.

draft with experts of his or her choice. After release for consultation, comments are expected from EU/EEA/EFTA countries, other regulatory authorities (e.g., the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Health Canada), industry associations, scientific and academic societies, patients’ groups, and health care professionals. Unless otherwise indicated, guidelines come into operation 6 months after their adoption. The current EMEA guideline on AEDs11 was drafted from April 1998 to September 1999, commented on from October 1999 to April 2000, and adopted in November 2000, and it came into operation in May 2001.

Specific EMEA Guidance on Antiepileptic Drugs

The specific EMEA position concerning the development of AEDs is described in the current note for guidance,11 but it also derives from the experience acquired through scientific advice and EU procedures that involved AEDs. Key aspects are reviewed in the sections below.

Global Development Plan for a New Drug

The clinical development of a new AED follows a stepwise approach. The preclinical data, including data on pharmacologic actions, toxicology, pharmacokinetics, and interaction profile, should be known before starting studies in humans. Initial human safety and pharmacokinetic data are usually obtained in healthy volunteers. For ethical reasons, the patient population selected for the initial clinical trials is usually represented by subjects with epilepsy who have continuing seizures in spite of several attempts to control the disorder with appropriate AEDs, used in combination and at optimized dosages. Therefore, the first application usually concerns the add-on indication in refractory partial seizures in adults, based on results of randomized, parallel-group, double-blind, adjunctive-therapy, placebo-controlled trials. A sufficient number of adolescents (over 12 years of age) should be recruited in the confirmatory studies. It is useful at this stage to submit a global development plan, showing which extensions are envisioned. In particular, the preclinical profile or some clinical exploratory studies (e.g., a double-blind cross-over study after an open enrichment phase) may suggest that the test drug has a potential for usefulness in other seizure types (e.g., seizure types associated with generalized epilepsies) or other syndromes. Once evidence for a beneficial effect has emerged from studies in adults, it is recommended to implement pediatric studies as planned in the clinical development plan and before registration of the product in adults (see guidelines on investigation of medicinal products in the pediatric population6). It may also be useful for the applicant to define at an early stage plans regarding the monotherapy indication, and which patient populations will be investigated for this purpose. A policy regarding elderly patients is also of importance. The development of parenteral formulations is encouraged. Besides bioequivalence and safety data, the demonstration of efficacy in status epilepticus may be an important objective with such formulations, although very little regulatory experience has been acquired in this particular domain.

Approach by Seizure Type and Epileptic Syndrome

Patients included in the clinical trials should be classified according to the International Classification of Seizures and, when possible, the International Classification of Epilepsies and Epileptic Syndromes. It is recommended to evaluate the whole spectrum of effectiveness of the test drug, not only according to the type of seizures (e.g., partial vs. generalized seizures), but also to the type of seizures associated with a specific epileptic syndrome. It is acknowledged that patients with partial epilepsies usually represent the initial target, since they are the most prevalent and a substantial percentage of them are not well controlled. Efficacy, however, should be evaluated for all the seizure types present in this condition, including simple, complex partial, and secondarily generalized tonic–clonic (GTC) seizures. A pooled analysis across several studies, optimally prespecified, may permit assessment of efficacy in the less frequent seizure types.

The other syndromes should be explored separately, which is the case for idiopathic generalized epilepsies and symptomatic/cryptogenic generalized epilepsies, including some syndromes specific for infancy and childhood (e.g., West syndrome or infantile spasms, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, Doose syndrome, Dravet syndrome). Addressing these syndromes will require evaluating the efficacy of an agent separately on the different seizure types present in the given condition (e.g., spasms, GTC seizures, absences, and myoclonic, tonic, or atonic seizures). The impact upon the other clinical features of the disease, such as cognitive outcome, should also be addressed. The global antiepileptic efficacy of an agent in a specific epileptic syndrome can only be claimed when efficacy has been shown for all seizure types associated with that syndrome.

In newly diagnosed patients, who often have a low number of seizures, it may be difficult to identify the seizure type or the syndromic context at the time of inclusion. Some apparently primarily GTC seizures may in fact be secondary to unrecognized partial seizures, particularly in patients with nocturnal seizures. Other GTC seizures may occur in an unrecognized context of idiopathic generalized epilepsy, in the absence of typical electroencephalographic (EEG) traits or other seizure types. The choice of including or excluding undetermined GTC seizures should be made in relation to the expected efficacy spectrum of the test drug, and of the comparator in case of active control trials. Some of these undetermined seizures may be classified later on in the trial, and it might be important to see whether response for these reclassified seizures or syndromes are compatible with the efficacy spectrum of the test product and of the comparator.

Development of Antiepileptic Drugs in Children

Pediatric studies should be conducted as early as the development of the test product allows, in order to avoid an excessive delay in obtaining a marketing authorization for children compared to the marketing authorization for adults. The pediatric needs in epilepsy were assessed by the CHMP Pediatric Expert Group,2 which identified the general need for studies of AEDs in refractory epilepsies. Existing data are generally insufficient in two particular domains: (a) pharmacokinetic, efficacy, and safety data of the newer AEDs in refractory epilepsies in young children, particularly under the age of 3 to 4 years, and (b) long-term safety including effects on cognitive function and brain maturation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree