50 The Role of Spinal Fusion and the Aging Spine

Stenosis without Deformity

KEY POINTS

Introduction

Basic Science

Radiographically, cervical stenosis is often diagnosed using a radiographic measurement called the Pavlov ratio. This ratio is defined as the ratio between the sagittal diameter of the spinal canal and the sagittal diameter of the vertebral body, as measured on a lateral radiograph. A ratio of greater than 1 is considered normal, while a ratio of less than 0.8 is considered to be diagnostic for spinal stenosis. A cervical MRI can help determine the etiology of the compression if the source is a herniated disc or a redundant ligamentum flavum. Additionally, an MRI can show any evidence of spinal cord compression, such as a lack of cerebrospinal fluid around the spinal cord and/or myelomalacia within the cord itself. A CT scan can be used to diagnose bony abnormalities such as osteophytes or hypertrophied facet joints.

Stenosis in the Cervical Spine

Case 1

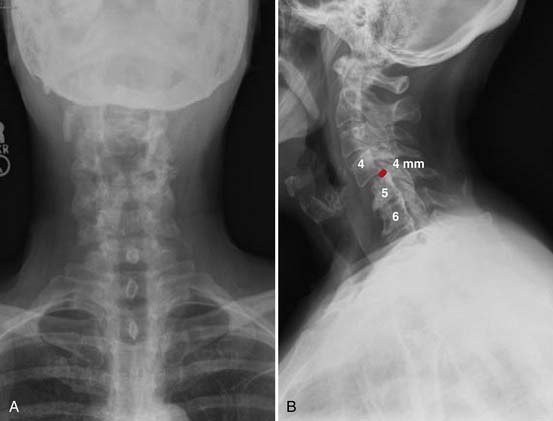

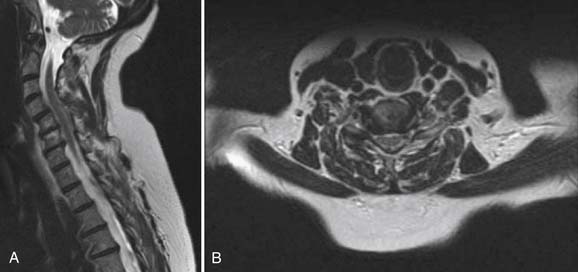

Radiographs, seen in Figure 50-1A and B, demonstrate loss of normal cervical lordosis, severe spondylosis, and a spondylolisthesis of C4 on C5. Sagittal and coronal MRI cuts, seen in Figure 50-2A and B, demonstrate significant spinal stenosis, loss of normal disc height, and severe spinal cord compression with myelomalacia.

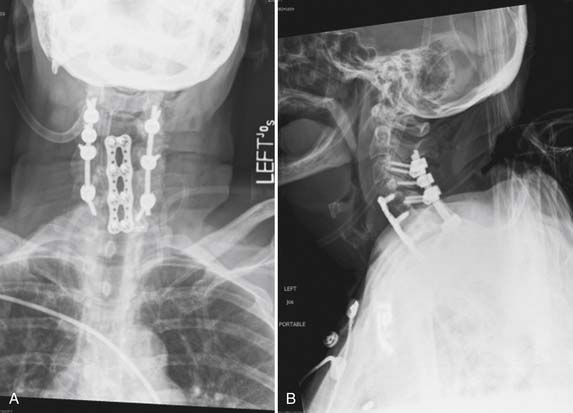

The patient was taken to the operating room for a combined anterior and posterior cervical decompression and fusion. Discectomies and interbody fusion were performed with allograft spacers and an anterior plate at C4-5, C5-6, and C6-7. This portion of the procedure restored normal lordosis and addressed the anterior pathology, including reduction of the spondylolisthesis at C4-5. The posterior procedure included laminectomy from C3 to C7 with screw and rod fixation from C3 to C7 as well (Figure 50-3A and B).

Clinical Practice Guidlines

The location of the compressive pathology in cervical stenosis is important, as it dictates the operative approach. Cervical stenosis due to a central or moderate-sized posterolateral cervical herniated nucleus pulposus is best treated with an anterior approach, in order to adequately remove the compressive pathology. This anterior cervical discectomy is typically combined with a fusion. Fusion is achieved with or without instrumentation, consisting of an anterior plate and screws. Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) has been described with good results without the use of instrumentation. An anterior cervical discectomy (ACD) without fusion is rarely performed today, and is almost never performed for multilevel disease. Discectomy without fusion has been reported in a prospective, randomized trial to be equivalent to ACDF for the treatment of cervical radiculopathy.1 For the treatment of myelopathy, ACD without fusion has been reported to result in good relief of neck and arm pain as well as a 76% rate of return to work.2 However, ACD without fusion has been shown in other case series to be associated with worsening of preexisting cervical myelopathy in 3.3% of cases.3 Worsening of symptoms after ACD without fusion was also reported by Nandoe Tewarie et al in a retrospective review of 102 patients evaluated up to 18 years after surgery.4 While ACD alone has been shown to be successful in the treatment of cervical myeloradiculopathy, the possibility of worsening of symptoms, combined with the difficulty of revision of anterior cervical surgery, makes this a possible yet unattractive surgical option.

If the compressive pathology is secondary to redundant ligamentum flavum, hypertrophied facet joints, or other posterior pathology, then a posterior approach allows the surgeon to directly decompress the offending agent. A posterior-only approach is only indicated if neutral or lordotic alignment of the cervical spine is maintained. A kyphotic deformity in the cervical spine often mandates an anterior approach to restore the normal cervical sagittal alignment. Decompression from a posterior approach consists of laminotomy, laminectomy, or laminoplasty. Removal of significant portions of the facet joints should be avoided in order to avoid causing iatrogenic postlaminectomy cervical kyphosis. Raynor et al reported a cadaveric study comparing the potential degrees of instability on biomechanical testing of intact specimens, and following 50% facetectomy, and 70% facetectomy. The conclusion of this study was the recommendation that a facetectomy should involve less than 50% of the facet joint in the absence of fusion, in order to avoid spinal instability.5 Postlaminectomy kyphosis after posterior cervical decompression alone is common when there is evidence of hypermobility on preoperative flexion-extension radiographs. A cervical fusion should be considered after posterior decompression if:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree