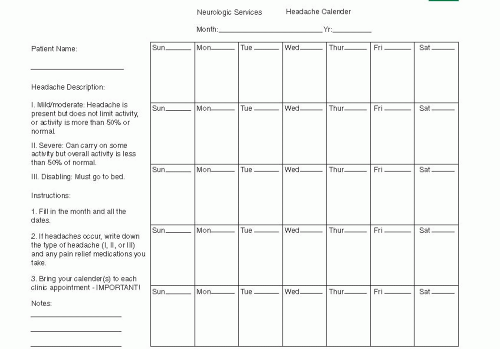

FIGURE 49.1 Example of a calendar for recording headache with intensity indicated by amount of temporary disability related to the headache. |

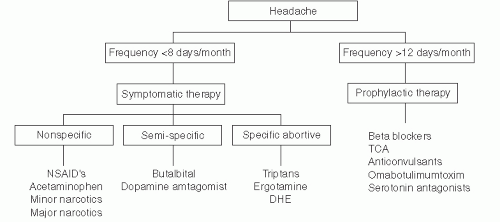

(relatively) specific abortive therapies. An algorithm for migraine therapy is presented in Figure 49.3.

TABLE 49.1 Key Features of a Headache Profile (Complete a Profile for Each Type of Headache) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Analgesics. The simplest therapy for acute migraine is a nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID) such as aspirin, ibuprofen, or naproxen sodium, all available as over-the-counter preparations and all effective for a many patients; larger dosages (e.g., 975 mg of aspirin, 800 mg of ibuprofen, or 550-825 mg of naproxen sodium) may be required. Addition of an antinauseant such as promethazine or hydroxyzine (25 to 50 mg) may be helpful in relieving both gastrointestinal symptoms and migraine pain.

Acetaminophen (APAP) is an analgesic that lacks anti-inflammatory action. Some patients find 650 to 975 mg of APAP to be effective for early/mild migraine headache.

The next step would be to try a more migraine-specific abortive drug (see I.D.3.). If this is not effective, then judicious use of a short-acting opiate/opioid can be considered.

“Narcotics” (opiates/opioids).

Self-administered narcotics. These include codeine (30 to 60 mg), hydrocodone (5 to 10 mg), and oxycodone (5 to 10 mg). All can relieve pain but may not affect other migraine symptoms. Use of promethazine or hydroxyzine with the narcotic extends the analgesic effect of the narcotic and helps relieve gastrointestinal symptoms induced by migraine or the narcotic itself.

Narcotic agonists-antagonists. Butorphanol, a prototypic narcotic agonistantagonist, commonly prescribes for migraine “rescue” is available as a nasal

spray that delivers 70% of the potency of intramuscular (IM) injection at 1 mg per “puff.” Use of 2 to 4 mg by nasal spray may produce significant pain control and prevent a trip to the emergency room. If intranasally administered butorphanol fails, injection of 2 to 4 mg of butorphanol or 10 to 20 mg of nalbuphine can be considered. These drugs stimulate opiate receptors at low doses but also act as narcotic antagonists and can elicit withdrawal symptoms at higher doses. Although these drugs have a lower habituating potential because they are κ receptor agonists, habituation can occur. The major side effects are dysphoria and hallucinations in addition to sedation. They cannot be used with any other narcotic because this may produce antagonism and narcotic withdrawal syndrome.

Clinician-administered narcotics. If the above treatmenmts are ineffective, use of a narcotic such as meperidine (50 to 150 mg) or morphine (5 to 15 mg) may be indicated. These agents usually are given intramuscularly but can be given intravenously (IV) at lower dosages. Promethazine or hydroxyzine at 25 to 75 mg usually is quite effective as an adjuvant agent when given with a narcotic. Generally speaking, whether administreted by patient or healthcare provider (HCP), the use of narcotics should be limited to patients who have only occasional severe headaches that are refractory to other nonspecific analgesic approaches or to the relatively specific abortive therapies discussed in I.D.3.

Ergotamine, Isolated from the rye fungus in 1925, ergotamine was the first abortive medication intended for migraine. It stimulates most of the aminergic receptors and consequently has many pharmacologic actions. It stimulates the 5HT-1-B and 1-D receptors as avidly as does sumatriptan.

Ergotamine can cause coronary vasoconstriction, and there have been several reports of myocardial infarction associated with ergotamine use. It also can cause vasoconstriction in the digits; this typically is of no clinical significance, but with long-term use of ergotamine peripheral cyanosis, acroparesthesias, and peripheral neuropathy may result. It remains unclear whether these findings are related to microvascular constriction, including constriction of vasa nervorum, or whether ergotamine has a separate and direct neurotoxic effect.

Frequent administration of ergotamine may result in medication overuse headache (MOH). The consensus is that ongoing use of ergotamine more than 10 days per month can produce MOH.

Because of ergotamine’s side effects and potential toxic effects, and because the triptans are equally if not more effective, ergotamine now is prescribed infrequently.

Triptans. This is a relatively new class of medications synthesized specifically for the treatment of migraine. Investigations of serotonin have identified four classes of receptors: 5HT-1 (presynaptic), 5HT-2 (postsynaptic), 5HT-3 (related to the g-protein system), and 5HT-4 (related to transporter function). The triptans are 5HT-1-B, 1-D receptor agonists (with lesser effects on the 5HT-1-A and 1-F receptors). These medications have been found to be remarkably effective for the symptomatic relief of migraine.

Mechanism of action. Peripherally via their action on the 5HT-1-B receptor, triptans constrict the intracranial arteries. This activity is highly cerebroselective, but the drugs do exert some relatively minimal coronary vasoconstrictive effect (see I.D.3.b(3)).

In the peripheral nervous system, 5HT-1-D receptors reside at the presynaptic terminals of nerves (chiefly the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal) which supply head pain receptors located on dural-based blood vessels. Stimulation of these 5HT-1-D receptors inhibits the nerve’s release of neuropeptides, which— otherwise left unchecked—would provoke the relevant blood vessel to leak proteins that produce so-called neurovascular inflammation. The resulting inflammation in turn can further sensitize trigeminal nerve endings and reinforce transmission of head pain signal.

In the CNS, the 5HT-1-D receptor is present on neurons within the TNC, as well as the locus ceruleus, dorsal raphe nucleus, and other brainstem structures. Some triptans (rizatriptan, zolmitriptan, and naratriptan) are CNS penetrant, whereas sumatriptan and ergot derivatives are less able to cross the blood-brain barrier in its normal state. Because all triptans have similar CNS side effects, however, it is postulated that during migraine attacks the bloodbrain barrier opens, and drugs with lower lipophilicity and thus typically less CNS penetration can enter the CNS during the attack.

Whether the major effect of the triptans in stopping migraine is peripheral (through 5HT-1-D receptors at the trigeminovascular junction within the meninges) or central (through antinociceptive 5HT-1-D receptors located on CNS neurons) continues to be a matter of debate. Perhaps the triptans’ antimigraine effect requires both.

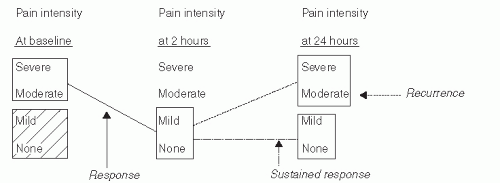

Clinical trials. The first clinical trials involved sumatriptan, and the methodology developed for those trials has set the standard for all subsequent trials involving symptomatic antimigraine therapy. Understanding how the trials were conducted may serve to help understand the drugs, their use, and their limitations. A brief summary is given below.

The chief outcome variables assessed were level of pain intensity and presence versus absence of nausea, vomiting, photophobia, and phonophobia.

Pain was reported as none, mild, moderate, or severe by the patient’s own internal standard.

Subjects were instructed to administer the study drug only when their acute head pain became moderate or severe.

The primary criterion of success was pain reduction from moderate/severe at the time of drug administration to mild or none (relief), or none (painfree) at 2 hours (see Fig. 49.4).

Secondary measures included the following: remission of baseline nausea, photophobia, or phonophobia at 2 hours; recurrence of moderate or severe headache within 24 hours; sustained pain-free at 24 hours; and change in headache-related disability at 2 and 24 hours after administration. Table 49.2 lists the seven triptans and the sumatriptan/NSAID compound currently available. In clinical trials, those oral triptans with longer half-lives (frovatriptan and naratriptan) have been associated with a somewhat lower response rate at 2 hours and a lower incidence of early recurrent headache

than the “fast-acting” oral triptans. The triptan formulation with the shortest half-life and Tmax—subcutaneously administered sumatriptan—is the most likely to produce headache relife at 1 and 2 hours but also is associated with a relatively high incidence of early recurrent headache.

Which oral triptan is “best?” Head to head studies involving “active comparators” (i.e., triptan vs triptan) have done little to provide an answer, if one exists. Treximet, the oral compound containing sumatriptan (as Imitrex RT) and naproxen sodium was demonstrably superior to oral sumatriptan, but that drug’s effect relative to its components administered simultaneously but independently or to others of the oral triptan class is unknown. From a clinical standpoint, however, there appears to be significant idiosyncrasy in the response of migraine patients to triptan therapy. A tripans that significantly benefits one patient may be completely ineffective for the next (and vice versa), and in the individual patient the failure to respond to one triptan does not necessarily predict failure to respond to others within the class. The cause(s) underlying these idiosyncrasies remain unclear

Adverse effects. The most common adverse effects of the triptans include somnolence, fatigue, asthenia, nausea, and dizziness. Chest discomfort (typically described as “pressure”) or a sensation of neck “squeezing” occur in a significant number of patients. The chest symptoms are thought to be related to stimulation of esophageal receptors with consequent esophageal spasm, but at times prudence dictates that a cardiac origin be excluded.

The major, clinically significant adverse events related to triptan therapy involve the heart. There are 5HT-1-B receptors on the coronary arteries, and both in vitro and in vivo studies have indicated that administration of a triptan potentially can cause as much as a 20% reduction in the diameter of coronary arteries. If the patient has a significantly stenotic atherosclerotic coronary lesion, then, this 20% constriction theoretically could be sufficient to occlude the vessel. There have been myocardial infarctions reported to occur in close temporal association with administration of triptans and also with ergotamine and DHE. Patients at risk for asymptomatic coronary disease should be screened appropriately before using triptans, ergotamines, or DHE. Patients with known cardiac disease should not take triptans.

As with their therapeutic effect, the triptans’ adverse event profile is relatively idiosyncratic. Tolerance to triptan therapy varies widely amongst migraineurs, and if a given patient has prominent side effects with use of one triptan, this does not necessarily guarantee that the patient will have the same experience with another.

Overuse of triptans can produce MOH. Triptan usage should be limited to not more than 3 days per week, 10 days per month and, generally, not more than 2 doses within a 24 hour period.

Administration. Table 49.2 lists the formulations and typical doses of the triptans currently available. Sumatriptan has the widest range of formulations (oral tablet, nasal spray, and subcutaneous (SC) injection), but for all the triptans the vast majority of patients utilize oral preparations. The benefits of oral administration must be weighed against the fact that many patients find such therapy to be inconsistently useful for migraine headache of moderate-to-severe intensity and typically much more effective if employed earlier in the attack, when pain is mild to moderate.

The rapidly melting tablet formulations of rizatriptan and zolmitriptan have achieved good acceptance owing to their convenience; they are no more effective—or rapidly effective—than the conventional tablet formulations of those drugs. Sumatriptan or zolmitriptan nasal spray can be used when the patient is too nauseated to take medication orally and disinclined to self-inject. The response time for zolmitriptan nasal spray is modestly faster than that of its oral counterpart, and that of sumatriptan nasal spray is roughly equivalent to the tablet.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree