Chapter 77 Thoracic Discectomy

It has been estimated that up to 20% of the population has a thoracic disc herniation, as evidenced by MRI.1,2 However, the need for discectomy is relatively rare. Surgery for removal of thoracic disc herniations is thought to constitute less than 4% of all disc operations.3,4 Historically, these operations have been associated with suboptimal outcomes for various reasons, in part because of diagnostic delays. These delays are a result of the rarity of symptomatic thoracic discs and the lack of a characteristic presentation pattern. It is hoped that a growing awareness of this disorder will lead to better outcomes as a result of earlier treatment. Additionally, there is uncertainty about the natural history of this disease. There is no consensus regarding the indications for disc removal. Most surgeons generally avoid prophylactic surgery for disc herniation; however, this practice has not been based on prospective studies. Generally, surgery is reserved for patients with severe, intractable radicular pain or for those with myelopathy, especially when it is progressive or severe. Finally, there are numerous operations for the removal of these lesions. Regrettably, no universally accepted selection criteria exist to help determine the best operation for each individual situation. Recently, surgical selection guidelines were proposed based on a large series of ventrolateral and lateral operations, the well-documented success of groups using the transpedicular approach, and preliminary experience with newer procedures, including transthoracic thoracoscopy, retropleural thoracotomy, and transfacet pedicle-sparing approaches (Table 77-1).5–9

TABLE 77-1 Surgical Approaches for Herniated Thoracic Discs

| Surgical Approach | General Indications |

|---|---|

| Ventral | |

| Transsternal | Upper thoracic spine Densely calcified centrolateral |

| Ventrolateral | |

| Transthoracic/ thoracoscopic | Densely calcified centrolateral Selected mildly calcified centrolateral |

| Retropleural | Selected high-medical-risk static severe myelopathy |

| Lateral | |

| A. Extracavitary | |

| B. Costotransversectomy | A and B, selected densely calcified centrolateral Mildly calcified centrolateral |

| C. Parascapular | C, upper thoracic spine calcified centrolateral |

| Dorsolateral | |

| Transfacet pedicle-sparing/transpedicular | All soft herniated discs Calcified lateral Mildly calcified centrolateral All high-medical-risk except densely calcified centrolateral |

Until the 1950s, laminectomy, with or without disc removal, was the treatment of choice for the surgical management of this disorder. Logue’s historical review in 1952 revealed the poor results achieved using laminectomy.10 Consequently, other methods of performing discectomy were developed. These operations were intended to improve the exposure to the ventral spinal canal throughout the thoracic spine. Although these approaches were successful at improving access to the disc space, they were technically formidable and associated with considerable morbidity. Each of these approaches has a unique set of potential complications; it is important to be aware of them so that they can be avoided. This chapter emphasizes these other methods and focuses on the advantages and disadvantages of each procedure. Fourteen contemporary thoracic disc series are summarized, with special attention given to the reported complications. In closing, a new management paradigm for the treatment of symptomatic thoracic discs is presented.

Surgical Approaches for Thoracic Discectomy

Dorsal Approaches

Laminectomy

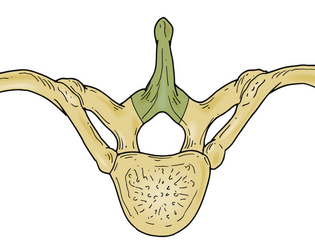

The initial approach used for thoracic disc herniation was laminectomy, either with or without disc removal. In 1952, Logue10 reviewed the thoracic discectomy literature and found that the results were poor. A significant percentage of patients were left paraplegic. Although the precise reasons for these results were not known, it was postulated that laminectomy alone did not significantly reduce the ventral forces created by a thoracic disc herniation acting on the spinal cord.4 Additionally, when discectomy was performed, spinal cord manipulation was generally poorly tolerated. The limited space available for the spinal cord, as well as the comparatively tenuous blood supply, was thought to increase the susceptibility of the thoracic spinal cord to injury during disc removal (Fig. 77-1).

Advantages and Disadvantages

Although laminectomy is technically the simplest decompressive spinal operation, the only indication for its use in thoracic disc disease may be in the treatment of thoracic spondylosis.11

Recent Experience

Black described a modified laminotomy/medial facet approach using a unilateral interlaminar laminotomy involving the superior and inferior laminar arches, as well as the medial 2 to 3 mm of the facet joint. The dural edge is exposed to establish boundaries for the cord, and an Epstein stomping curet is used to push the disc downward and away from the cord. This technique was used to remove 11 discs in seven patients. Effective treatment was reported; only one patient reported transient increased weakness compared with preoperative weakness.12

Dorsolateral Approaches

Transpedicular Approach

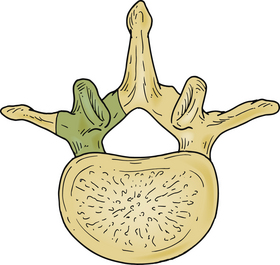

Patterson and Arbit13 first reported the transpedicular approach in 1978. It was initially performed on three patients with thoracic disc herniations. Two of the patients had complete resolution of their symptoms, and the third markedly improved. Subsequently, several other series have also reported excellent results (Fig. 77-2).

Technique

The patient is placed in the prone position and taped to the table to facilitate rotation away from the surgeon during the disc removal. The spinous process, lamina, and facet joints are exposed using a linear midine incision. Most of the facet joint is removed, as is the pedicle caudal to the disc space. The pedicle is drilled out flush with the vertebral body. A small cavity measuring 1.5 to 2.0 cm in depth is created in the vertebral body to enable depressing the overlying disc away from the ventral dura mater. Additionally, whenever necessary, hemilaminotomies are performed to visualize the dorsolateral dura mater.11,14–19

Advantages

This approach is considerably less invasive than most other operations for thoracic disc removal, particularly the transthoracic (TT) and the lateral extracavitary (LECA) approaches. Using this less invasive approach is thought to lessen perioperative pain, shorten hospital stays, and enable earlier return to premorbid activity.4,8,16,20,21 The surgery avoids problems associated with thoracotomy, rib resection, and extensive muscle dissection. Operating time and blood loss also appear to be less than with other surgeries.

Disadvantages

Critics of this procedure point out the limited ability to visualize across the spinal canal, making decompression of the central and contralateral portions of the disc a relatively blind procedure. Sometimes, difficulty is encountered in managing calcified and intradural disc fragments. We8,13,16 believe that safety is enhanced by using specially designed thoracic microdiscectomy instrumentation (Fig. 77-3) and endoscopic techniques.4,8,16 Although some report being able to remove intradural fragments and central, densely calcified discs using the dorsolateral techniques,5,13,16,19,22 we4 have not had success with these entities. Dense calcifications involving the dorsal margin of the disc space tend to adhere strongly to the ventral dura mater.4,17 The possibility of significant dural adherence may lead one to use one of the ventrolateral or lateral procedures in those situations.4,17

The final disadvantage of this procedure relates to the removal of the facet-pedicle complex, without the ability to place an interbody graft. It has been reported that patients operated on using the transpedicular approach have somewhat disappointing results from the standpoint of localized back pain.8,13,16,19,23 The desire to improve these results led to the development of the transfacet pedicle-sparing approach.4,8,18 It was postulated that the avoidance of pedicle removal should minimize postoperative back pain. The preliminary experience has suggested that this, in fact, may be the case.

Recent Experience

Bilsky reviewed 20 cases performed between 1982 and 1992 at New York Hospital in which the transpedicular approach was used for thoracic discs (lateral or centrolateral calcified or soft discs). No postoperative instrumentation was used for stabilization; however, no patient suffered from postoperative spinal instability-related pain or delayed kyphosis.15 Levi et al. have published a contemporary series of 35 patients operated upon via a unilateral transpedicular approach. Good results were obtained in 15 patients, fair results in 11 patients, and no improvement in 8 patients, and 1 patient was paraplegic after surgery. They also did not find evidence of clinical or radiographic instability.24 Chi et al. describe a mini-open transpedicular thoracic discectomy in which tubular retractors and microscope visualization are used in performing a transpedicular thoracic discectomy. Eleven patients were operated on using the mini-open disectomy approach versus four patients operated on using an open dorsolateral approach. Patients operated on using the mini-open approach had less blood loss and a greater improvement in their modified Prolo score compared with the open procedure. At long-term follow-up, the modified Prolo score was similar for both groups of patients.25 Jho published a series of endoscopic transpedicular thoracic discectomies in 25 patients. A 1.5-cm trocar is placed at the junction of the lamina and facet via a paramedian incision. The medial portion of the facet, the very lateral portion of the lamina, and the rostral one third of the pedicle are removed using a high-speed drill. A limited amount of spinal cord dura and nerve root are exposed, and then a 70-degree lens endoscope is introduced, allowing for a discectomy to be performed under direct visualization. This surgery was able to be performed on an outpatient or overnight stay basis; no surgery-related complications were reported.26

Transfacet Pedicle-Sparing Approach

The transfacet pedicle-sparing approach was developed as a simpler alternative to the formidable ventrolateral and lateral operations for the treatment of thoracic disc disease.4,8 Initially, morphometric studies were carried out and improved the authors’ orientation to the disc space and ventral spinal canal, thereby aiding discectomy. Cadaveric studies demonstrated that a keyhole facetectomy alone, without associated pedicle or lamina removal, did not sacrifice the exposure achieved with the transpedicular approach.4,8 Although the safety and overall effectiveness of the transpedicular approach have been well documented,13,16 it was hoped that avoidance of pedicle removal and limiting the amount of facet resected would improve localized back pain results.8

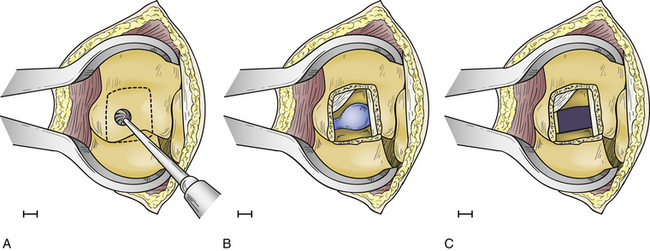

Technique

The operation is performed with the patient in the prone position on a radiolucent frame and spinal table. The arms are placed at the sides, and the patient is taped to the table. Anteroposterior (AP) fluoroscopic imaging is used to identify the appropriate disc space. A 4-cm linear skin incision is centered over the disc space. The paraspinal muscles are subperiosteally reflected laterally, exposing the ipsilateral spinous process, lamina, facet joint, and transverse processes above and below the disc space. A small, self-retaining retractor is placed, and the fluoroscope is introduced to verify the correct level and the precise location of the underlying disc relative to the facet joint. Once this relationship is ascertained, a high-speed drill is used to facilitate a partial facetectomy (Fig. 77-4A). Care is taken to preserve the lateral margin of the inferior and superior articular processes of the facet joint and the entire pedicle directly caudal to the disc. When the partial facetectomy is completed, the underlying neuroforaminal fat is coagulated with bipolar cautery. The nerve root, which exits the spinal canal under the more rostral pedicle, is rarely encountered, except in the upper thoracic spine (Fig. 77-4B). The underlying anulus is coagulated and incised. The disc herniation is removed using conventional microdiscectomy techniques (Fig. 77-4C). As with the transpedicular approach, no fusion is required.8

Advantages

Advantages of the transfacet pedicle-sparing approach may include diminished operating time, decreased blood loss, and limited bone and soft tissue removal. Like the transpedicular approach, perioperative pain, hospital stay, and return to premorbid activity appear to compare favorably with the more formidable ventrolateral and lateral approaches.4,17,19 When necessary, multiple disc herniations may be treated.14 The exposure is identical to that provided by the transpedicular approach. Preservation of the pedicle may improve long-term localized back pain results.4,17,19

Disadvantages

The disadvantages are the same as for the transpedicular approach.13,16 Specially designed thoracic microdiscectomy instrumentation8 and, on occasion, open endoscopic visualization of the disc and ventral dural mater have been helpful in enhancing safety during the disc removal.8,16

Recent Experience

Zhang et al. have recently published a series of 18 patients treated with the transfacet pedicle-sparing approach with dorsal instrumentation and fusion. Although the transfacet approach was published with the goal of avoiding dorsal instrumentation, the patients in this series all had additional segmental instrumentation. All patients had good exposure of the disc space and good decompression of the spinal cord. These investigators experienced a complication rate of 33%, with six of the patients requiring additional surgery; five had wound infections or seromas requiring washout and one required revision of a misplaced screw.27

Minimally Invasive Approaches

A number of minimally invasive microendoscopic discectomy techniques have been advocated, all using a dorsolateral approach and an endoscope for visualization. Although the series are not large, they have all demonstrated adequate access and visualization with removal of the thoracic discs with decreased morbidity compared with open approaches.22

Technique

The basic underlying instrumentation used in all approaches involves a dorsolateral approach, endoscope, and tubular dilators. The patient is usually placed in a prone position; however, Jho has placed the patient in a lateral position for an endoscopic transpedicular thoracic discectomy.26 The approach used by Fessler et al. involves a prone position on a radiolucent Wilson frame.28 A localizing radiograph is obtained to determine the level of the thoracic disc. A paramedian skin incision is made at the level of the disc, approximately 3 to 4 cm lateral to the midline. A series of tubular muscle dilators are then placed, and the tubular retractor is placed to form a working port for the endoscope. The endoscope is passed down the center of the tubular retractor. Under endoscopic visualization, the muscle and soft tissue is cleaned off at the level of the transverse process and lateral aspect of the facet. A drill then excises the junction of the transverse process and lateral facet, allowing access to the disc. The pedicle is identified, and drilling of the superior aspect of the caudal pedicle is performed to allow access to the thoracic disc. The disc anulus is identified and cut, and the endoscope is tilted for a 30-degree visualization similar to a transforaminal-type approach. The disc is removed, and a down-going curet or a Woodson elevator is used to push down the disc fragment away from the spinal cord. After the discectomy is performed, the tubular retractor is removed and the wound closed.

Disadvantages

The main disadvantage of a minimally invasive endoscopic approach is the learning curve and familiarity with the anatomy. This approach should be performed by individuals with facility using the endoscope and previous experience with the open dorsolateral approach. Minimally invasive approaches can turn out to be maximally invasive approaches when the learning curve is steep. Visualization is good at the point of entry and is limited to familiarity with the anatomy seen on the endoscope.

Recent Experience

Two main series using this approach have been published.22,26 Perez-Cruet et al. have a series of seven patients operated on using a minimally invasive thoracic microendoscopic discectomy (TMED).22 Results demonstrated no morbidity with this approach, good access, and quick return to work. No case required conversion to an open procedure. Jho reported a series of endoscopic transpedicular approaches also with excellent results. His series is based on a more extensive pedicle takedown, coming in more medially than Perez-Cruet. Results were also excellent for visualization, disc removal, and quick return to work.26

Lateral Approaches

Lateral Extracavitary Approach

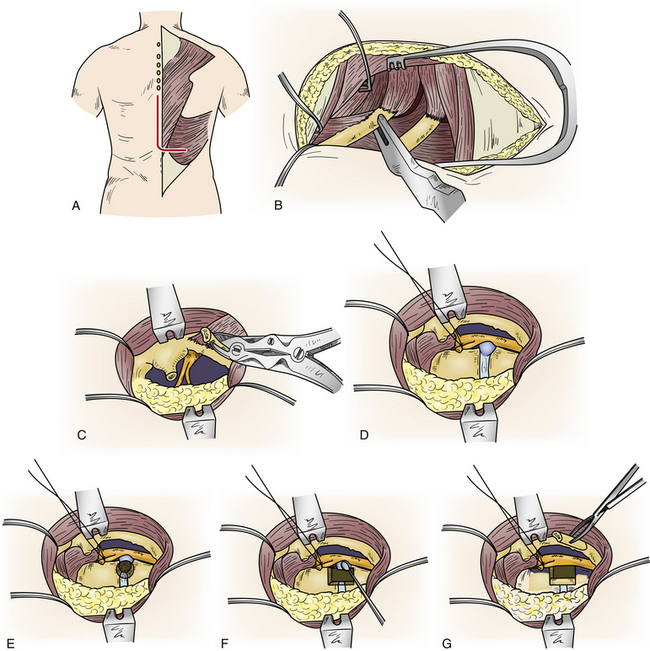

LECA was developed and refined by Larson.29 It was first performed for the management of Pott disease. It provides the best exposure to the ventral spinal canal of all lateral operations. Large thoracic discectomy series have documented its safety and efficacy17,30 (Fig. 77-5).

Technique

The procedure is performed with the patient prone and taped to the table with arms at the side. The skin incision consists of a hockey-stick incision, with the vertical portion centered over the area of pathology11,18,29,30 (see Fig. 77-5A). Caudally, the incision is gently curved off the midline for 8 to 12 cm, enabling the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and fascial flap to be rotated far laterally. Alternatively, a paramedian lunar-shaped incision may be used. The erector spinae muscles are subperiosteally dissected off the dorsal ribs and transverse processes and flapped medially.31 The erector spinae muscle complex may be wrapped in a moistened laparotomy pad and gently retracted medially. Intraoperative imaging helps ensure removal of the rib that articulates with the correct disc space (see Fig. 77-5B). Once the proximal 8 to 12 cm of rib is resected, the underlying intercostal nerve is identified and traced into the neural foramen (see Fig. 77-5C). The pedicle caudal to the disc is identified and removed, exposing the lateral aspect of the dura mater (see Fig. 77-5D). At this point, the dorsal third of the disc space is removed. Care is taken to leave intact the dorsal-most margin of disc and the posterior longitudinal ligament (see Fig. 77-5E). The dorsal-caudal quarter of the rostral vertebra is drilled out, as is the dorsal-rostral quarter of the caudal vertebra. This creates a cavity so that the remaining dorsal disc and posterior longitudinal ligament can be gently depressed away from the spinal cord (see Fig. 77-5F). The ventral dura mater can then be inspected either directly, with small dental mirrors, or with an endoscope. The rib, which was resected to facilitate exposure of the disc space, is then fashioned into strut grafts and carefully impacted into the cavity (see Fig. 77-5G). The ventral dura mater and spinal canal are then inspected again to ensure that there is no encroachment by the bone grafts.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree