Goodman and Gotlib’s integrative model for the transmission of risk to children of depressed mothers.

The level of specificity in this model demonstrates that the impact of maternal depression on children is complex. Starting with the depressed mother, the subsequent impact on children is mediated and moderated by several variables. Living with a depressed mother means not only inheriting risk but also increasing the likelihood of exposure to environmental stressors (e.g., family dysfunction, a parent’s negative cognitions, behaviors, and affect), which leads to the dysfunction of neuroregulatory mechanisms. In this model, the term “mechanism” is synonymous with the statistical concept of mediation. In turn, the presence of one or more of these risk mechanisms is associated with various adverse outcomes in children, including, for example, cognitive dysfunction, problems with affect (e.g., difficulties with emotional regulation), and behavioral and interpersonal difficulties, as well as specific psychopathology not limited to depression.

Goodman and Gotlib (1999) argue that these pathways are not straightforward and involve a number of interrelated components and mechanisms. For instance, they review evidence to demonstrate each of the following steps: (1) depressed mothers exhibit negative cognitions, overt behavior, and affect; (2) because of these depressive symptoms, mothers are unable to attend to their child’s social and emotional needs; (3) this inadequate parenting has adverse impacts on children’s psychosocial development; (4) through modeling, children acquire depressive symptoms that (5) place them at risk of developing depression themselves. The age of the child when exposed to maternal depression is highlighted as an important factor in appreciating the risks for children, alongside the acknowledgement that children are often exposed to several episodes of maternal depression throughout their childhood. Moreover, the bidirectional nature of family relationships is incorporated whereby children’s behaviors are seen to affect their mothers’ depression, mother–child interactions, and parenting behaviors. Finally, the model incorporates several moderating variables that indicate when or under what conditions children’s outcomes might vary, and includes factors such as the availability of fathers and their mental health; the child’s age, temperament, and intelligence; and the timing and course of the mother’s depression. The model is able to explain, at least partially, why it is that not all children whose mothers suffer from depression will become depressed, and, conversely, why not all children who become depressed have a mother with depression.

Goodman and Gotlib provide a critique of the available evidence, including methodological weaknesses and gaps, and, by doing so, critique their own model. They concede that “although none of the mechanisms or moderators proposed in the model can be considered to have been supported conclusively, support for some components of the model is more robust than for others” (p. 475). They raise other questions arising from research gaps such as the extent to which the various highlighted mechanisms are associated with adverse outcomes on children.

The Goodman and Gotlib model is extensive and is based on a comprehensive overview of a wide range of empirical data. The updated Goodman (2007) paper includes practice, prevention, and treatment implications largely missing from the original model. As Hammen (2003) points out, maternal depression is not just about depressed women but is also about families, given that children often contribute to negative interactions between parent and child, mothers were often raised in dysfunctional families themselves, and the environment in which they live can be stressful. Goodman (2007) is aligned with this view when she describes her practice implications as “transactional,” and advocates the involvement of fathers, the reduction of stressors in families (such as marital conflict), the screening of children, and the delivery of age-appropriate child interventions that enhance children’s coping skills and their understanding of parental depression. She concludes with an acknowledgement that not all children will develop psychopathology; hence, prevention and treatment initiatives need to target those most at risk, based on better understanding of the factors that moderate risk (Goodman, 2007).

Nicholson and Henry (2003): the family recovery model

The ecological model of family recovery was originally proposed to provide a broad-brush-stroke structure for developing the evidence base on interventions for parents with mental illness and their families – to serve as a “translational bridge” (Nicholson and Henry, 2003). The family recovery model concerns intervention targets for service provision rather than mediators and moderators of the impact of parental mental illness on children’s outcomes over time. The model was originally grounded in the literature on child developmental psychopathology and parents with mental illness, and research on parent training interventions (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2009; Nicholson et al., 2008; Taylor and Biglan, 1998).

Following an in-depth provider survey and systematic site visits of programs across the USA, key intervention approaches, theories, and assumptions were identified (Hinden et al., 2005, 2006; Nicholson et al., 2007). Rigid adherence to a single theory or practice was often felt to be inappropriate by program staff members, who largely defined themselves as eclectic in theoretical orientation and pragmatic in addressing day-to-day problems. Providers shared a common commitment to family-centered, strengths-based approaches as key to success in working with families living with parental mental illnesses. The essential service components provided by the majority of programs included (1) some form of case management (emotional support and problem solving, coordination of multiple services, and crisis management) and (2) parent support, education, and skills training.

The task in refining further iterations of the family recovery model was to integrate the literature and research findings into a working model of intervention targets, and translate this model into treatment or rehabilitation approaches drawing from research on “what works” for parents in general and for parents living with disabilities conveyed by mental illnesses specifically. The psychiatric disability and rehabilitation perspective was chosen for several reasons:

(1) The acknowledgement that mental illness may convey disability in particular role domains (e.g., parenting, employment) places it as a condition on the list along with intellectual, developmental, sensory, and physical disabilities (National Council on Disability, 2012). This suggests that parents with psychiatric disabilities fall under the purview of US federal and state legislated policies and programs for parents with disabilities and their families, with protections and accommodations theoretically protected by law.

(2) The notion of disability is role or context dependent. That is, a person may be disabled in one role or setting, but not in another. A parent with mental illness may be able to function well as a parent, but not be able to sustain employment, for example. Therefore, from the disability perspective, a parent living with mental illness is not automatically assumed to be a “bad” parent, allowing for the identification of individual strengths and recognition of differences.

(3) Because disability is context dependent, rehabilitation interventions may be targeted to the context (e.g., accommodations in role expectations, or the physical or service environment) as well as to the individual (e.g., target training to learn or relearn skills). Parents may function as well as possible with adequate accommodations and tailored supports.

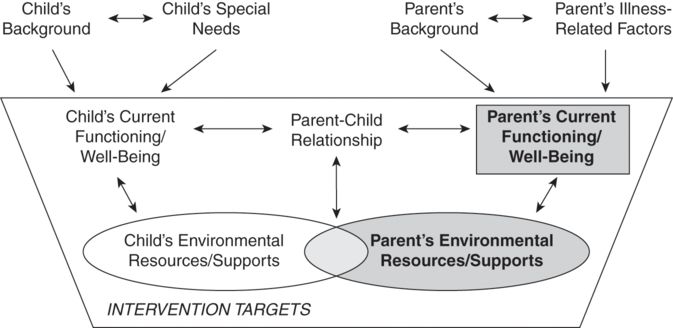

A contextual model of disability demands that attention be paid to person–environment interactions and underscores the relevance of an ecological perspective on parenting, rehabilitation, and recovery (US Department of Education, 2007). The family recovery model lays out the relationships between parent and child characteristics, the family, and the environment, and the interactions and transactions among them to suggest targets for intervention and pathways for recovery (Nicholson and Henry, 2003). Outcomes are optimized when parents and children are functioning as well as possible, their interactions are as positive as possible, and they have access to and benefit from the appropriate environmental resources and supports (i.e., formal treatment and rehabilitation, relevant benefits and entitlements, and informal resources like friends and family). Specific intervention targets suggested in the model include the parent’s current functioning, the child’s current functioning, their interactions, and their environmental resources and supports (see Figure 1.2).

Nicholson and Henry’s family recovery model.

The family recovery model suggests intervention targets and provides a foundation for translating domains and relationships into theoretically sound intervention approaches and outcomes through the psychiatric rehabilitation and recovery lens. Interventions must be linked to evidence-informed theory, with conceptually consistent outcomes relevant to parents and families. Essential service components, such as (1) case management and (2) parent support, education, and skills training documented in previous research on parents with mental illness; and a shared provider commitment to family-centered, strengths-based service delivery suggest relevant change strategies for intervention development and testing (Hinden et al., 2006).

The family recovery model aims to promote exploration and evaluation, rather than explanation, to facilitate contributions to the evidence base of interventions for parents living with mental illness and their families.

Hosman, van Doesum, and van Santvoort (2009): a developmental model of transgenerational transmission of psychopathology

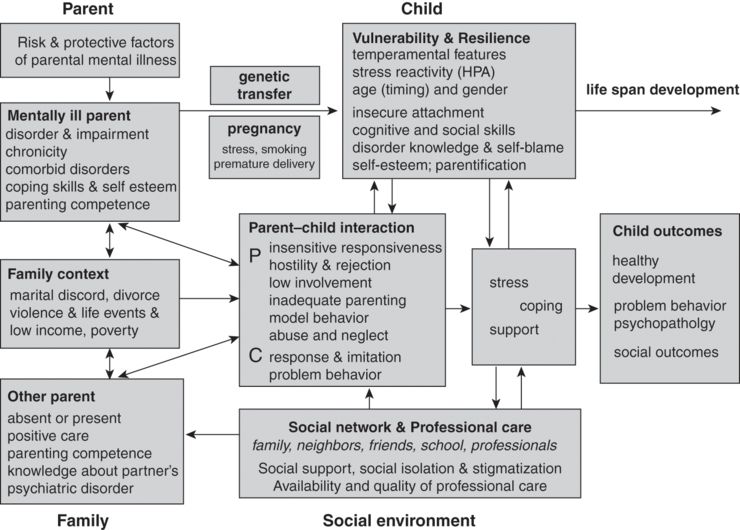

Hosman and colleagues (2009) present a developmental theoretical model for families where parents have a mental illness, based on what they call “practice-based and theory-based knowledge and related evidence,” the sum of which includes epidemiological and clinical studies, clinical and preventive practices, and their own extensive contacts with children and families. They also cite the Goodman and Gotlieb (1999) model in their work. The resulting framework has been used to shape prevention policy, family interventions, and the research agenda in the Netherlands. The model acknowledges both mothers or fathers with a mental illness and cites research across a range of diagnostic disorders. It highlights multiple, interacting domains including parents, children, family, social network, professionals, and the wider community. Within each of these domains, specific risk factors and protective factors are identified including genetics, prenatal influences, parent–child interactions, the family environment, and the broader context in which the family lives (see Figure 1.3). A developmental perspective underlies the model, in which a child’s specific developmental tasks, starting with pregnancy, and other age-related risk factors are indicated.

Hosman, van Doesum, and van Santvoort’s (2009) developmental model of transgenerational transmission of psychopathology.

Employing the concepts of equifinity and multifinality, the authors consider the question of disorder specificity as well as the broad spectrum of risk across diagnostic groups. They conclude that specific to the disorder are genetic and biochemical factors and role modeling of parental behavior where children copy their parent’s dysfunctional coping behavior. Common risk factors include poverty and isolation. This model also highlights various protective factors that tend not to be disorder specific such as the quality of social support accessible to the child and family. The translational implications for these arguments are important, with the conclusion that “children have much in common across different parental diagnoses. On the other hand, children and their parents might have specific questions and needs relating to the parental disorder (e.g., knowledge about the disorder, how to cope with symptom behavior). These disorder-specific issues should also be addressed as part of a comprehensive approach” (p. 253).

Adrian Falkov: the family model (2012)

The family model has been developed over the last fifteen years by Adrian Falkov, on the basis of his experience as a psychiatrist treating mentally ill parents and their children in England and Australia. The model extends his original work, Crossing Bridges, which was developed as a training and organizational development package for mental health services. The family model provides a framework for mental health service responses that might be provided for families though it is acknowledged that “No single service can meet the needs of all family members” (Falkov, 2012, p. 8).

While family or systems theory is not cited, the model primarily focuses on interactional relationships between parents and their children, and other interrelationships between multiple individuals and factors proposed to influence parent and child mental health (see Figure 1.4). For example, Falkov (2012, p. 80) notes that “the various experiences of different individuals in a family are influenced by, and influence, each other – a system of interconnected relationships between family members, and between the family and their neighbourhood, community and service networks.” Accordingly, the six links or influences among the following domains frame the family model:

(1) “an adult/parent-to-child influence” – where the parental illness affects the child

(2) “a child-to-parent influence” – where the child’s behavior and emotional state affect the mental health of the parent

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree