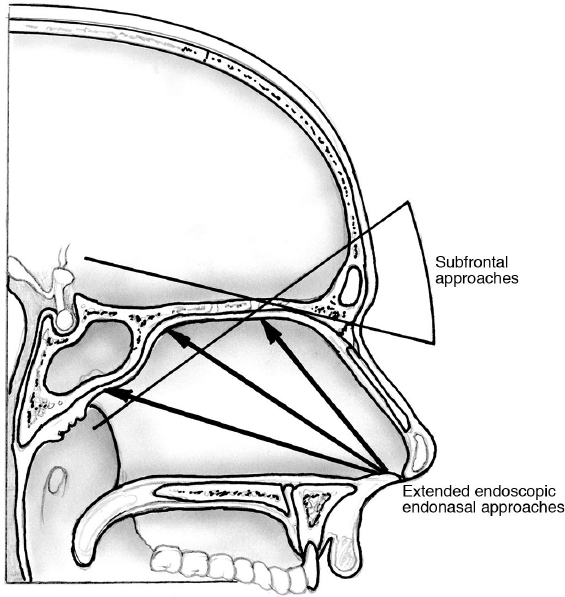

14 Transcranial Approaches to the Skull Base When deciding on a surgical approach to the skull base, the surgeon must consider the lesion, the patient, his or her own preferences and expertise, as well as the surgical team and the environment in which the team operates. The surgeon must gauge the abilities of the surgical team (e.g., is the planned surgery within the team’s capabilities and training?), and must assess the equipment and resources available (e.g., is neuronavigation available?). Undertaking approaches with which the surgeons and the surgical team have little or no experience is irresponsible, unfair to the patient, and could lead to avoidable complications. • The lesion and its effects on the patient must be carefully considered. Asymptomatic lesions rarely need a surgical approach on a first assessment, unless the working diagnosis suggests a poor prognosis if left untreated. Asymptomatic patients who have lesions that have been shown to be growing, particularly in eloquent areas with impending neurologic deficit, should have appropriate counseling regarding the natural history of the disease and the pros and cons of surgery. Symptomatic patients should be assessed for a correlation between the symptoms and the lesion. Those patients in whom the lesion and symptoms cannot be deemed related should undergo a similarly focused discussion with their surgeons regarding the benefits and risks of surgery in a frank and honest fashion. In many of these circumstances, observation of the patient with serial imaging may be the most prudent approach. Patients who have lesions that correlate well with their symptoms (e.g., the patient with a large pituitary adenoma and a bitemporal visual field defect) should be considered candidates for surgery after medical assessment and an assessment of the likelihood of being helped by a surgical approach. Patients who are unlikely to be helped by surgery (e.g., the patient with a small cavernous sinus meningioma and ophthalmoparesis) should be managed by alternative techniques such as radiosurgery (see Chapter 30). Considerations of the patient’s age, physiological status, and comorbidities should be carefully weighed before recommending surgery. Whether surgery will hold a reasonable likelihood of benefit depends on the symptom–anatomy correlation and the degree to which effects on critical structures can be reversed, or at the very least critical function can be preserved and damage minimized. • Once it is decided that a patient will benefit from surgery, the surgeon and the team must determine the goals of surgery (e.g., tissue diagnosis, debulking, resection, decompression), the most appropriate approach, and the methods to achieve this approach. The approach must be determined by considering the eloquence of the surgical corridor and the degree to which the corridor will provide sufficient access to achieve the goals of surgery. For example, if the goal of surgery is to achieve a gross total resection but the approach selected would only provide a subtotal resection or biopsy, then either the goal or the approach should be reconsidered. The goal must align with the proposed surgical approach. The goal and the surgical plan should be discussed with the patient and the family. • Determining the surgical approach is based in part on an evaluation of the size, texture, vascularity, and firmness of the lesion; the degree of extension to cranial nerves, vessels, and brain structures; the degree of brain edema and shift of structures; the intracranial pressure and hydrocephalus; and the number of “compartments” (e.g., a cranial fossa, a paranasal sinus, a particular bone, an extracranial space) in which the lesion resides. Whether the lesion is intradural or extradural must be determined. Also, the degree to which vascularized or nonvascularized tissues are necessary to repair a particular corridor, once lesion management has been completed, must be assessed. The surgeon must ensure that a reconstruction can be performed before embarking on access. Example 1: A 40-year-old, otherwise healthy, patient with no prior surgery presented with a large sellar and suprasellar mass with visual compromise and normal prolactin levels. A lesion in a large sella turcica would be best treated via an approach through the sphenoid sinus using appropriate local tissues for repair. Example 2: A 60-year-old patient presented with an extensive basal frontal lesion with marked frontal lobe edema, and extension through the dura, arachnoid, pia mater, and skull base into the ethmoid and sphenoid bones. The patient will likely need an approach that provides wide access to each compartment and the ability to reconstruct the neuro-aerodigestive tract barriers, ideally with vascularized tissue, as well as management of intracranial and CSF pressures. This might mean a subfrontal approach with orbitocranial osteotomy and pericranial flap reconstruction. A failure to consider these issues in a comprehensive manner when planning whether and how to approach a particular patient with a particular lesion is doomed to fail. The surgical plan should clearly describe the surgical approach and the imaging to be used. The plan should be reviewed by all members of the team. A comprehensive, standardized, specialty-specific checklist should be developed in a meeting of all surgical, anesthesia, and nursing team members. The following issues should be discussed: surgical goals, patient positioning, antibiotic and seizure prophylaxis, blood and fluid treatment plans, deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis, anesthesia and monitoring techniques, the availability and functioning of surgical equipment, management of intracranial pressure and cerebrospinal (CSF), tissue reconstruction, and the postoperative discharge plan. • Cerebrospinal fluid diversion. Patients at risk of CSF leak or in need of brain relaxation (or both) should be considered for CSF diversion. CSF diversion can be done via a lumbar drain (LD) or an external ventricular drain (EVD). Lumbar drains are considered for those patients in whom the basal CSF cisterns will be accessed late in the procedure and in whom brain relaxation will facilitate the access, but not place the patient at undue risk of herniation. Those patients with large tumors that cause significant mass effect or shift of structures from one compartment to another should be considered for EVD rather than LD if CSF drainage is thought to be of use and if access to the basal cisterns will occur late in the procedure. Patients undergoing procedures that involve wide opening of the basal cisterns and opening of the barriers of the neuro-aerodigestive tract will require CSF diversion in the intensive care unit for several days postoperatively. Those who are at low or no risk of postoperative CSF leak can have their drains removed and the site stitched before they leave the operating room. Optimum performance of the team requires constant communication among all members. Any unexpected findings or change in plans of any of the discussed preincisional issues should be discussed immediately. Staff changes during the procedure should be communicated, and proper continuity of care ensured by standardized means of communications such as checklists. A thorough explanation of the intraoperative events and findings should be clearly documented in the patient record and communicated to the staff who will be managing the patient postoperatively, such as the intensive care unit staff. The open approaches selected should facilitate (1) viewing the lesion with maximal safe access, (2) treating the lesion (e.g., excision), (3) avoiding complications with critical structures, and (4) providing the best ability to reconstruct. Every surgical plan should avoid complications by having a thorough plan for (1) access, (2) treatment, and (3) reconstruction. Views, surgical approaches, and techniques can be thought of, or classified, in a number of different ways. The type of skin incision does not define a surgical approach. Rather, the incision is created after a consideration of the following issues, to define the sort of access through the skull. The accomplished skull base surgeon will consider each issue with every patient: 1. Whether the relation to the skull base is (a) from below upward, or “subbasal”(e.g., transsphenoidal); (b) from above downward or “suprabasal” (e.g., pterional); or (c) by traversing the skull base (e.g., transcranial), or “transbasal.” 2. Whether the lesion is viewed from (a) anterior, (b) anterolateral, (c) lateral, (d) posterolateral, or (e) posterior. 3. Whether the bones transgressed are (a) frontal, (b) temporal, (c) occipital, (d) sphenoid, (e) ethmoid, (f) maxillary, or (g) a combination of bones (e.g., frontal-temporal, transsphenoidalethmoidal). This conceptualization can be further subdivided according to the components of the particular bone transgressed (e.g., translabyrinthine, transcochlear, or transcondylar). 4. Whether the approach is primarily for the central midline or non-midline structures or both (see Chapter 2, Fig. 2.3b, page 12). 5. Whether the approach is primarily extradural, intradural, interdural, or transdural. 6. The relations with specific brain structures such as a lobe of the brain (e.g., subfrontal lobe or paracerebellar). 7. The natural brain pathways to the skull base or the positions to which the skull base lesion may extend (e.g., through fissures such as the frontal interhemispheric fissure, the sylvian fissure, or the posterior interhemispheric fissure). 8. Whether the resection of the lesion will occur as a whole (en-bloc) or progressively (piecemeal). These approaches are classified according to whether they approach the lesion at the skull base from below (i.e., subbasal), from above (suprabasal), or directly parallel to or through the base (transbasal)1,2 (Fig. 14.1). The suprabasal and transbasal approaches generally go through the frontal bone, and the subbasal ones extend through the nasal cavity, ethmoid bones, sphenoid bone, and occasionally the maxilla. These approaches can be used for lesions from the frontal sinus to C2 and even further along the cervical spine. However, their widest extent is in the anterior and central skull base. Those anterior subbasal (subcranial) approaches are generally limited laterally by the optic nerves or medial orbital walls and internal carotid arteries (ICAs), whereas the suprabasal or transbasal ones are not.3 Fig. 14.1 Anterior approaches to the skull base. According to the surgical angle and the potential transgression of the bone, the approaches can be subbasal, suprabasal, or transbasal (see text). The figure also shows the possible surgical angles of the endonasal approaches. In deciding whether to approach a midline lesion from above or below, in addition to considering the optic nerves and ICAs, the slope and particular anatomy of the anterior cranial fossa floor in relation to the position of the lesion should also be considered. This is particularly true for lesions, such as meningiomas, that are in the region of the planum sphenoidale. Intradural lesions along the planum in patients who have a steeply sloping planum are difficult to access from a purely anterior subfrontal approach unless the planum is drilled. These patients may be better served by an extended transsphenoidal approach as long as there is no encasement or extension of the tumor around the ICAs or anterior cerebral arteries (ACAs). If there is encasement, an anterior-lateral approach may be better. • For the anterior approaches mentioned above, the degree to which one might have to use brain retraction is also a deciding factor. In this respect, one needs to consider the degree to which the lesion extends away from the floor. Although it may seem paradoxical, the higher the lesion extends up from the skull base, the more one might consider a more basally oriented approach. For example, for a large frontal fossa lesion that extends upward significantly, one may choose to perform an orbitocranial osteotomy in addition to a frontal craniotomy in order to avoid frontal lobe injury from brain retraction, if the relaxation provided by CSF drainage is insufficient. The less it extends away from the skull base, the more likely that simple measures such as an LD and a simple craniotomy will be sufficient. • The subcranial approaches generally avoid brain retraction but are limited in their intracranial extent laterally without significantly more dissection. They also demand a high degree of experience and ability to reconstruct. • Because the subbasal anterior approaches tend to be limited by the position of the lesion in relation to the ICAs, lesions that significantly extend laterally may be better approached suprabasally. Access that interrupts the neuro-aerodigestive tract barriers to CSF must be reconstructed to prevent meningitis. If CSF leak is not a risk, then a vascularized repair is less critical, although one should always be prepared for a CSF leak. If the CSF barriers are penetrated, placement of CSF diversion is strongly recommended before accessing the lesion. If the lesion is large, but not so large as to place the patient at risk of herniation of brain, then an LD is often helpful. This decision is largely defined by the lesion and its relation to critical structures like the ICAs. In general, the more the lesion extends across the midline and extends beyond the contralateral ICA, the more likely the surgeon would want to be able to access the contralateral ICA for control in the event of an ICA injury. Furthermore, if one is taking a purely interhemispheric approach and requiring access to purely midline structures such as the interhemispheric fissure, the more likely one would want a bilateral but more limited lateral approach. This approach is indicated for any lesion, intradural or extradural, of the anterior cranial fossa, including the frontal sinus, unilateral or bilateral, such as a tumor, aneurysm, or traumatic CSF leak. See subsection “Should the Lesion Be Approached from Above or Below the Skull Base”, above. The patient is placed in a supine, semi-reclining position, with the head higher than the heart. The head is in neutral position, not turned for midline or paramidline lesions. For more laterally placed craniotomies to access lesions on both sides of the ICA or optic nerves, the head can be turned 15 to 30 degrees. The vertex is extended to allow the frontal lobes to relax by gravity. If fascia lata or fat is required for a repair, it should be prepared at this time and included in the sterile field. The position of the lesion and the frontal sinus should be projected and marked onto the scalp. The bony opening should be planned first and then the optimal incision planned afterward. In centers without frameless stereotaxy, this can also be accomplished by reference to surface landmarks and preoperative imaging correlation. The incision can be unilateral or bilateral depending on whether the bony approach is unilateral or bilateral, how close to the midline the bony exposure is planned, and cosmetic considerations. For “mini” approaches, the incision can be placed above, in, or below the eyebrow. Local anesthetic with adrenaline for all incisions is recommended unless contraindicated (e.g., prior radiation, extensive scar, infection, allergy, hypertension, vascular concerns). The standard unilateral incision is a reverse question-mark shape starting in a crease close to the tragus and continuing to the midline of the hairline. For those cases where an orbitocranial osteotomy is fashioned, the incision can be taken lower and repaired with a fine subcuticular stitch. Careful hemostasis of the scalp should be maintained at all times by the eventual use of scalp clips (e.g., Raney clips) or hemostats. • For patients requiring a bifrontal approach, a bony opening at the midline or, for cosmetic reasons (to avoid incisions near the forehead), a coronal incision is used. This generally extends from helix to helix, or if more basal exposure or temporal exposure is required, from the tragus or even lower. Although a number of variations exist on the coronal exposure (e.g., zigzag, sinusoidal) (Fig. 14.2), the one that is in the same position as the coronal suture or parallel to it is the one that is most often used in neurosurgery. This variation maximizes the length of any pericranial/periosteal vascularized flap and yields very good cosmesis. The length of a pericranial flap should be estimated on the preoperative imaging, and the position of the coronal incision should be planned with this length in mind. Always try to preserve all the layers of the scalp and the superficial temporal artery and vein in the opening. These are all vascularized layers that can be important to the health of the scalp in the event of radiation, or be used if vascularized tissue is required. • In the event that the supraorbital nerve is contained within a foramen, it usually can be extended into a notch with the use of an osteotome directed away from the globe. The supraorbital artery and vein should be preserved whenever possible with the nerve. If the distance between the superior orbital rim and the supraorbital foramen is more than 5 mm, often it is best to just sacrifice the nerve rather than create a large defect. The dissection is carried onto the superior orbital roof at this point, particularly if a transbasal approach with an orbitocranial osteotomy is planned. The orbital contents are protected with cottonoids, and the dissection proceeds with communication with the anesthesia team in the event of a trigeminalvagal response due to the manipulation of orbital contents. The scalp is either stitched carefully or held in place with rubber bands connected to the stitches or by carefully placed hooks. The scalp is kept moist throughout the remainder of the procedure. Prior to craniotomy, the brain should be relaxed by means of an LD, hyperventilation, osmotic diuretics, or combinations of these maneuvers. The decision regarding the extent of the craniotomy has been described above. If a bilateral exposure is planned, control of the superior sagittal sinus (SSS) is crucial. It is quite safe to place one or more bur holes directly over the sinus using a perforator with an automatic stop function that halts the perforator once it is through bone as long as the perforator is held perfectly perpendicular to the bone. Carefully strip the SSS from the bone prior to elevation of the bone flap. Place one or multiple bur holes elsewhere. Bone dust can be preserved and placed into antibiotic solution for the remainder of the surgery and, if required, can be used in the reconstruction. If control of the SSS is not required, then place a bur hole high up on the frontal bone adjacent to the SSS to avoid any deformity of the forehead. If only a tiny hole has been created in the frontal sinus, it can be repaired safely with bone wax. If it is a larger opening, strip and remove the frontal sinus mucosa carefully. Use a fine high-speed drill to remove any remaining fragments of mucosa. The sinus can be de-functioned after complete exenteration with fat packing and plugging of the frontal-nasal duct. • There is no controlled or randomized evidence for removal of the posterior wall of the frontal sinus, so-called cranialization of the sinus. Apart from the case of trauma with comminuted fractures of the posterior wall of the frontal sinus (see Chapter 34, page 846), it seems that there is no role for cranialization in the contemporary management of skull base lesions. Apply tack-up stitches to the edges of the dura. If the lesion is extradural, transbasal, or has extensive vascular supply arising extradurally (e.g., meningioma), or an orbital osteotomy is planned, the extradural space is now developed. After appropriate brain relaxation, use a dural or periosteal dissector to carefully elevate the anterior skull base dura. If needed, the ethmoidal and other penetrating arteries can be bipolared and divided. If a midline exposure is sought, the midline is dissected and a decision regarding the olfactory nerves ought to have been made preoperatively and discussed with the patient. Preservation of one set of olfactory nerves is desirable but must be predetermined based on the goals of the surgery. If the nerves are divided, the dura should be over-sewn immediately. If the midline is required, the SSS is suture ligatured carefully, with one suture ligature above and one below the planned position of the transection of the SSS, which ought to be as low to the skull base as possible. Dural access to the base can be achieved by cutting along the base, with a flap created along the base or along the SSS (near the foramen cecum) if the hemispheric fissure is the main corridor of access. Wherever possible, all bridging veins should be preserved. Lesion management is discussed in the chapters that address each type of lesion. Some key points: • Normal anatomic structures will be fixed in their origin from the brain and exit from the skull base; for example, the trigeminal nerve will always exit the pons on its midpoint and lateral aspect regardless of what the tumor has done to the pons. Its branches will always exit at the superior orbital fissure (SOF) (V1), foramen rotundum (V2), and foramen ovale (V3). So whenever tumors or other lesions distort the anatomy, try to find the normal structure where one would expect to find it entering or exiting the space of interest. • Preserve the arachnoid. Because blood vessels and nerves run in the subarachnoid space, preserving the arachnoid and always keeping the normal arachnoid with the patient will generally preserve the critical vessels, nerves, and brain. Close the dura primarily. If the dura cannot be repaired, a duraplasty can be performed using autologous tissue such as the fascia lata or temporalis fascia. If other tissues are available, try not to use the pericranium for dural reconstruction, so as not to compromise the integrity of the scalp. A variety of commercially available dural substitutes can also be used. Some forms of these products may not be acceptable to the patient because of cultural or religious reasons, so the source of such products should be discussed preoperatively with the patient. The dural closure can be reinforced with fibrin glue, although no randomized controlled evidence supports this practice. If there has been a broad opening of the CSF pathways and the neuro-aerodigestive pathways are opened, vascularized tissue coverage is the goal. The preserved periosteal flap is the one most used for this purpose. If it is absent and the scalp is in satisfactory condition, a galea flap or vascularized free flap such as a radial forearm flap based on the superficial temporal can also be used. In bringing the periosteal flap down, care should be taken to be certain that the flap is not kinked over the base of the craniotomy opening. If the flap has to take a sinuous course up over a large bridge of bone at the base and the flap is at risk of necrosis, it may be best to remove the orbital bar so as to provide a flat and straight path for the vascularized flap. The flap should not be under tension and should be long enough to reach to the deepest part of the opening. The flap can be placed directly against the dura, or against a fat graft adjacent to the dura. If possible, the flap should be sutured to the dura at several spots so that it does not move in the closure. If there is a wide opening into the nasal cavity, it is also possible to place a fat graft and fibrin glue external to the pericranial flap. In the setting of a good flap, repair of the bone defect in the anterior skull base is not always necessary (see also Chapter 27, page 711). Care should be taken to ensure that any bony defects of the forehead that are visible are repaired with inert materials. If the frontal sinus has been opened, and even if repaired, cements such as methyl methacrylate are contraindicated because of the high risk of infection. In this instance, inert titanium mesh or plates can be used. In the absence of these options, bone dust and sutures can be utilized. A subgaleal drain can be used with or without a cranial wrap dressing. There are a number of modifications of the transbasal approach.5,6 The simplest involve drilling through the ethmoid and/or sphenoid planum in order to access the paranasal sinus regions. The more complex approaches incorporate an osteotomy that basically extends the approach to a transbasal point of view. The osteotomies can include only the orbit, the frontal-nasal complex, and the orbit, or the bilateral orbital roofs and the nasofrontal complex. The osteotomy(ies) can be combined with a drilling through the ethmoids and/or the sphenoid, in order to access the nasal cavity, the clivus, or down to C2. Complications can be classified as follows: (1) related to the approach (e.g., frontalis palsy, supraorbital numbness, alopecia along the incision, SSS injury, hemorrhage, anosmia, periorbital swelling, ptosis, diplopia); (2) related to the treatment of the lesion (e.g., neural injury such as cranial nerve or pituitary stalk, venous/arterial/perforator infarction, brain contusion, seizures); (3) related to the reconstruction (e.g., cosmetic deformities, CSF leak, meningitis); or (4) systemic (e.g., deep vein thrombosis, pneumonia). This approach is suggested for the treatment of anterior skull base lesions, such as olfactory groove meningiomas, craniopharyngiomas, and dural arteriovenous fistulas8,9 (see Chapter 19, Fig. 19.2, page 461). The patient is placed in the supine position, with the head fixed in a head clamp in the neutral position with the nose straight up, slightly elevated from the level of the heart, and with the face horizontal (parallel to the floor) or slightly extended. Surgical Anatomy Pearl Spare all cortical veins in the dural opening. Be careful about those that enter the sinus in the top of the anterior third of the SSS. The dura can be opened with the base at the SSS or the base at the frontal skull base. A wider opening in the dura is worthwhile to avoid dividing the bridging veins and to enable working around these veins. The sphenoid bone is the key to the skull base, and so it is no surprise that the transsphenoidal sinus (TSS) approaches have the most versatility in approaching lesions of the skull base. A number of variations exist in the TSS approaches, but the basic premise to unlock the sphenoid sinus and its adjacent neighbors remains constant. Access to the sphenoid sinus requires the establishment of a sufficient corridor in which to access and maneuver instruments at the skull base. This requires displacement or removal of part or all of the turbinates of the nasal cavity. The microscopic approaches generally displace and compress them using specula for the nasal cavity and displacement of the septum, whereas the endoscopic approaches tend to remove part or all of the middle and inferior turbinate depending on the area required for access. Although the microscope offers unparalleled stereoscopic vision, the endoscopic offers unparalleled panoramic vision and the ability to observe far beyond the midline. The initial access and mode of visualization differ, but ultimately, for midline structures, the techniques used at the tumor level are similar. For a description of the endoscopic approaches, both standard and extended, see Chapter 16. This approach offers a wider exposure to the sphenoid in the event of small nostrils, such as occurs in young children. Use of head fixation is optional. Most surgeons maintain a neutral head position, although some prefer the head laterally flexed toward the surgeon by about 10 degrees or with mild extension (no more than 10 to 15 degrees) and some with rotation by approximately 10 to 20 degrees. Maintaining the anatomic neutral position minimizes the chances for surgeon disorientation. In pituitary surgery, avoid hyperextension of the head, as it leads to an approach that is too anterior, reaching the planum sphenoidale instead of the sella turcica. Surgical Anatomy Pearl Check the anatomy of the sphenoid sinus septa carefully in the computed tomography (CT) scan before the approach. Surgical Anatomy Pearl Carefully localize the intrasphenoidal sinus anatomy: the planum sphenoidale superiorly, the sellar floor in the middle with cavernous sinuses and parasellar ICAs laterally, and the clivus inferiorly with paraclival ICAs laterally (see Chapter 2, Fig. 2.15, page 54). The most caudal extension of the clivus resection enables visualization and access to the atlas and to the tip of the odontoid process. The preparation of the nasal cavity and mucosa is similar to that in the sublabial approach. Surgical Anatomy Pearls Use the right length of speculum to reach the sinus; excessive opening of the speculum may cause skull base fractures (Fig. 14.5c,d). The position of the speculum in relation to the sphenoid sinus might eventually be checked by a lateral intraoperative X-ray. Disadvantages include long and narrow corridors, limited by the nasal structures, and limited exposure to the midline, particularly when visualized by microscope. These approaches generally avoid the frontal sinus (depending upon the sinus lateral extension) and may or may not involve removal of the temporal squamous bone in addition to the frontal bone. The frontotemporal craniotomy is the most common of these with variations such as the pterional, osteoplastic, frontotemporal orbitocranial, and the orbitozygomatic approach. Like the anterior approaches, these approaches can be classified as suprabasal, transbasal, and subbasal based on the views they provide. They can also be classified as intradural, interdural, or extradural. Fig. 14.6 shows a schematic representation of the angles of potential visualization of some anterolateral approaches. Fig. 14.6 Schematic representation of the angles of potential visualization of some antero-lateral approaches (pterional, supraorbital, extended frontotemporal). This is a unilateral approach that is very useful for lesions of the regions of the anterior and middle fossa floor. It cannot easily access the frontal pole and anterior or superior interhemispheric fissure, and it provides less direct visualization of the contralateral ICA. Although it provides a limited pericranial flap, it can provide a temporalis muscle flap for reconstruction. Much of what was described for the anterior suprabasal approaches applies to the frontotemporal craniotomy. The patient is placed in the supine, semi-reclining position, with the head higher than the heart. Often a shoulder roll is placed to minimize strain on the neck. The head is often turned 15 to 45 degrees, depending on the pathology. The vertex is extended to allow the frontal lobes to relax by gravity. See above (page 337). The standard unilateral incision is a reverse question-mark shape starting in a crease close to the tragus and coming to the midline of the hairline (Fig. 14.7). For those cases where an orbitocranial osteotomy is fashioned, the incision can be taken lower and repaired with a fine subcuticular stitch. For relatively small lesions in the posterior aspect of the middle fossa floor or tentorial incisura (e.g., basilar aneurysm), occasionally a straight incision or an inverted U-shaped incision centered just in front of the ear will suffice. Fig. 14.7 Anterolateral approaches, surgical position. Based on the surgical plan, different incisions can be used. Note the position of the superficial temporal artery and the frontal branch of the facial nerve. The dotted lines show the eventual incision on the forehead, which, whenever necessary, should be sutured with subcuticular stitches at the end of the procedure. As stated above, always try to preserve all the layers of the scalp and the superficial temporal artery and vein in the opening. These are all vascularized layers that can be important to the health of the scalp in the event of radiation, or can be used if vascularized tissue is required. Because these approaches rarely utilize a pericranial flap reconstruction, the pericranium is usually left attached with the other layers of the scalp. The scalp dissection is carried onto the superior orbital roof at this point, particularly if a transbasal approach with an orbitocranial osteotomy is planned. It is of paramount importance to understand the anatomy of the soft tissues in the pterional region (see Fig. 2.19, page 63). • If a free bone flap is planned, then the temporalis muscle is elevated after the interfascial dissection as described above. The temporalis is mobilized most commonly from inferior to superior and either it can be completely disconnected at the superior temporal line (STL) or a small cuff of muscle can be left at the STL. • If an osteoplastic flap is planned, the temporalis muscle is left attached to the bone and the bone flap turned. This technique is not possible if a transbasal orbitocranial or orbitozygomatic approach is planned. Surgical Anatomy Pitfall The temporalis muscle should not be denervated by any cuts across its belly in order to avoid postoperative atrophy.10 Prior to craniotomy, the dura should be relaxed by means of an LD, hyperventilation, osmotic diuretics, or combinations of these maneuvers. One or more bur holes can be used for the approach, with at least one placed in the “keyhole.” In the pterional technique, the bone of the pterion, the lateral sphenoid ridge, and the ridges of the orbital roof are drilled off. In the orbitocranial and orbitozygomatic approaches, this bone is removed en bloc and then replaced at the end of the procedure, usually providing less of a bone defect postoperatively. If access to the middle fossa floor is required, an extradural dissection is carried out along the floor. If this is extensive, this is usually combined with an orbitozygomatic (OZ) or a zygomatic arch osteotomy. The dissection is carried in an anterior to a posterior direction from the lesser sphenoid wing to the greater sphenoid wing to identify the foramen rotundum and foramen spinosum. The middle meningeal artery is carefully identified, bipolared, and divided. Any vascular supply to lesions can also be taken in this step. The foramen ovale and arcuate eminence can then be identified. If more dissection is required, the greater superficial petrosal nerve, which runs parallel and often on top of the petrous ICA, is identified and dissected using magnification allowing access to the horizontal petrous ICA segment. Surgical Anatomy Pearl The petrous ICA has no bony covering in 30 to 40% of cases, and if there is any bone, it is often a millimeter or thinner. • In the transbasal exposures or those requiring access to the infratemporal fossa, the middle fossa floor will be removed by high-speed drill under magnification. Tack-up stitches are routinely applied to the edges of the dura. In extradural lesions, stitches are placed in the inferior temporal dura and allowed to hang on hemostats. For intradural lesions, the dura is opened in a C-shaped fashion along the sylvian fissure and tacked up. • The decision of whether to open the sylvian fissure depends on the lesion and its relation to the arachnoid. Carefully study this fissure and consider the location on the preoperative imaging. It is often not necessary to open the dura for lesions of the lateral cavernous sinus wall or for lesions such as trigeminal schwannomas, which are truly interdural or only in Meckel’s cave and not in the subdural space. In these sorts of cases, an interdural approach is much preferred. For all aneurysms, that sit in the subarachnoid space, the fissure is opened. For lesions in the subdural space, such as meningiomas, the arachnoid is preserved along with the vessels of the sylvian fissure, if possible. Lesion management is discussed in the chapters addressing each lesion. A few points: • Identify the middle meningeal artery early at the foramen spinosum, bipolar it well, and clearly cut it. If necessary, pack the foramen spinosum with hemostatic material such as methyl-cellulose (e.g., Surgicel). • Identify the foramen rotundum and ovale and preserve the nerves within them. • Preserve all veins. Try more dissection and altering the approach before sacrificing a vein. Often with effort, they can be preserved, though it takes more time. Never take the vein of Labbé, especially if it is dominant. If there has been a broad opening of the CSF pathways and the neuro-aerodigestive pathways are opened, vascularized tissue coverage is the goal. The sphenoid sinus is most commonly invaded or opened between the foramen ovale and foramen rotundum. If so, a strip of the temporalis muscle can be transferred in the extradural position to repair any defect after the dura has been secured. • The flap should not be under tension and should be long enough to reach to the deepest part of the opening. The flap can be placed directly against the dura, and fat graft followed by fibrin glue can be placed into the sphenoid. If possible, the flap should be sutured to the dura at several spots so that it does not move in the closure. Care should be taken to ensure that any bony defects of the forehead that are visible are repaired with inert materials as described above. Defects in the sphenoid wing or lateral orbit can be replaced with bone cements or titanium mesh if the frontal sinus has not been breached. The frontotemporal-orbitozygomatic (FTOZ) approach, considered the workhorse of skull base surgery, is a modification of the frontotemporal craniotomy.11 By means of the extension of the frontotemporal craniotomy with an orbitocranial (OC) or orbitozygomatic (OZ) osteotomy, a larger surgical corridor allows wider and shallower access and more ability to access deeper and higher structures with less retraction12 (Fig. 14.8). This approach allows the surgeon a wider view of basal structures. The addition of the OC or OZ osteotomies increases the view angles by 75% in the subfrontal approach, 46% in the pterional approach, and 86% in the subtemporal approach.13 The OZ approach significantly enlarges the angles of maneuvering when compared with the pterional approach (about 37 degrees vs 27 degrees, respectively). The approach with maxillary extension offers a further, but less significant, widening of exposure in comparison with the OZ alone.12 This approach provides basal exposure of the anterior and middle fossa structures such as the cavernous sinus, as well as extradural access to the infratemporal fossa and paranasal sinuses.14 • The OC approach provides wider access to lesions placed anterior to the oculomotor trigone, whereas the extension to include the zygomatic arch provides wider access to those locations that are posterior to the oculomotor trigone such as the basilar artery apex and the interpeduncular region.14–17 Both the OC and the OZ provide access to the regions as described, regardless of pathology (e.g., aneurysms, craniopharyngiomas, pituitary macroadenomas, chordomas). By minimizing retraction, venous injury and contusion risks are minimized. Patient positioning depends on the location of the lesion; more anterior and central lesions require less head rotation than laterally placed and posterior lesions. For a lesion in the anterior clinoid process (ACP) region, the patient is placed in the supine position with the head fixed and elevated 20 degrees, slightly hyperextended and rotated contralaterally approximately 10 to 30 degrees, with the zygomatic bone positioned parallel to the floor. As stated above, preoperative lumbar drainage might be inserted; a small amount of CSF can be gradually drained before or during surgical maneuvers. Surgical Anatomy Pearls • The OZ approach can be full or partial (the zygomatic arch remains intact and only the orbit is opened14). • Orbitozygomatic craniotomies can be performed in one-, two-, or threepiece flaps.19 In general, the one-piece orbitozygomatic approach enables the frontotemporosphenoidal craniotomy to be elevated along with the orbitozygomatic osteotomy, whereas the two-piece orbitozygomatic approach elevates the frontotemporosphenoidal bone flap first and then the orbitozygomatic part is separated afterward.20 • The cuts of the OZ osteotomy are generally performed by using a reciprocating saw, but the use of the same footplate for the craniotomy has been advocated as a safe and quick approach.21 Reciprocating saws generally leave much smaller gaps in the bone cuts than do craniotomies with footplates. Surgical Pearl During osteotomy, self-retaining retractors may be used, not to retract the brain but for protecting the dura.

14.1 Presurgical Considerations Regarding the Approach

14.1 Presurgical Considerations Regarding the Approach

Intraoperative, Preincisional Considerations

Intraoperative, Preincisional Considerations

Intrasurgery Performance

Intrasurgery Performance

Specific Approaches

Specific Approaches

14.2 Anterior Approaches

14.2 Anterior Approaches

Should the Lesion Be Approached from Above or Below the Skull Base?

Should a Lumbar Drain Be Placed?

Bilateral or Unilateral Approach?

Suprabasal Approaches: Subfrontal Approach

Indications

Position

Navigation

Incision

Scalp Flap: Surgical Approach

Scalp Flap: Surgical Approach

If the preoperative plan includes opening the frontal sinus and performing a vascularized periosteal flap reconstruction, then it is easiest to leave the periosteal layer on the bone when elevating the scalp and to raise it in a second layer based on the supraorbital artery and nerve along the orbital rim. If there is a low likelihood of requiring a periosteal flap, it is best to elevate it together with the other layers of the scalp and leave it attached. If the flap is needed at the end of the procedure, it can be easily dissected with care using a No. 15 scalpel or with fine nontraumatic scissors. Care should be taken to leave the galea aponeurotica in place, especially on the first surgery.

If the preoperative plan includes opening the frontal sinus and performing a vascularized periosteal flap reconstruction, then it is easiest to leave the periosteal layer on the bone when elevating the scalp and to raise it in a second layer based on the supraorbital artery and nerve along the orbital rim. If there is a low likelihood of requiring a periosteal flap, it is best to elevate it together with the other layers of the scalp and leave it attached. If the flap is needed at the end of the procedure, it can be easily dissected with care using a No. 15 scalpel or with fine nontraumatic scissors. Care should be taken to leave the galea aponeurotica in place, especially on the first surgery.

The region of the frontalis branch of the facial nerve and the temporal fat pad should be managed carefully to avoid postoperative frontalis nerve palsy (see Chapter 2, Fig. 2.19, page 63). In coronal scalp incisions, this region should be managed the same way on both sides. In a unilateral approach, elevate the superficial fat pad and get to the deep fat pad and elevate both with the scalp. In a unilateral or bilateral approach, carry the scalp at least as far as the orbital rim. If an orbitocranial osteotomy is planned with exposure near or across the midline, the nasal frontal suture is exposed in the midline. If a more lateral exposure is required, the zygomatic bone to the orbitofacial foramen is exposed.

The region of the frontalis branch of the facial nerve and the temporal fat pad should be managed carefully to avoid postoperative frontalis nerve palsy (see Chapter 2, Fig. 2.19, page 63). In coronal scalp incisions, this region should be managed the same way on both sides. In a unilateral approach, elevate the superficial fat pad and get to the deep fat pad and elevate both with the scalp. In a unilateral or bilateral approach, carry the scalp at least as far as the orbital rim. If an orbitocranial osteotomy is planned with exposure near or across the midline, the nasal frontal suture is exposed in the midline. If a more lateral exposure is required, the zygomatic bone to the orbitofacial foramen is exposed.

Craniotomy

Variation: At least one bur hole is placed in the “keyhole” after some elevation of the temporalis muscle, even in purely frontal craniotomies. Four bur holes can be done, combined with the cranioplastic “bridge technique” that leaves small bridges of bone between the bur holes. When the craniotomy is replaced, the bone rests on these bridges, providing a perfect contour of the skull and biomechanical stability that usually obviates the need for expensive miniplates in simple craniotomies.4

Variation: At least one bur hole is placed in the “keyhole” after some elevation of the temporalis muscle, even in purely frontal craniotomies. Four bur holes can be done, combined with the cranioplastic “bridge technique” that leaves small bridges of bone between the bur holes. When the craniotomy is replaced, the bone rests on these bridges, providing a perfect contour of the skull and biomechanical stability that usually obviates the need for expensive miniplates in simple craniotomies.4

If a bifrontal craniotomy is required, the same set of holes are placed on the contralateral side. The craniotome is taken straight across the base of the frontal bone through the frontal sinus bilaterally. The basal cut should be taken as low on the frontal fossa as possible to provide skull base access without the need for frontal lobe retraction. In the event of a deep midline internal crest on the frontal bone, a bridge is left in the midline and then it is “cracked” in the same fashion as the other bridges.

If a bifrontal craniotomy is required, the same set of holes are placed on the contralateral side. The craniotome is taken straight across the base of the frontal bone through the frontal sinus bilaterally. The basal cut should be taken as low on the frontal fossa as possible to provide skull base access without the need for frontal lobe retraction. In the event of a deep midline internal crest on the frontal bone, a bridge is left in the midline and then it is “cracked” in the same fashion as the other bridges.

Frontal Sinus Exenteration

Dural Management

Lesion Management

Reconstruction: Dura Mater

Reconstruction: Pericranial Flap (Fig. 14.3)

Reconstruction: Bone and Soft Tissues

Transbasal Approaches: Uni- or Bilateral Orbital-Cranial Subfrontal Transbasal, Nasofrontal Transbasal

Variation: The approach may be limited to the midline, and done with a basal removal of the medial orbital and nasofrontal complex for malignant disease of the nasofrontal ethmoidal complex.1,2,7 This osteotomy can be extended unilaterally or bilaterally to the orbital roof and rim, in order to widen the working spaces.

Variation: The approach may be limited to the midline, and done with a basal removal of the medial orbital and nasofrontal complex for malignant disease of the nasofrontal ethmoidal complex.1,2,7 This osteotomy can be extended unilaterally or bilaterally to the orbital roof and rim, in order to widen the working spaces.

In the event that the osteotomies are performed, the pericranial flap reconstruction should be brought in under (inferior) to the osteotomy and the osteotomized piece should be drilled slightly to widen the space for the flap so as not to strangulate it by using a flap that is too tight fitting.

In the event that the osteotomies are performed, the pericranial flap reconstruction should be brought in under (inferior) to the osteotomy and the osteotomized piece should be drilled slightly to widen the space for the flap so as not to strangulate it by using a flap that is too tight fitting.

Orbital and orbito-nasofrontal osteotomies are replaced with the aid of titanium miniplates or, if these plates are unavailable, with heavy suture.

Orbital and orbito-nasofrontal osteotomies are replaced with the aid of titanium miniplates or, if these plates are unavailable, with heavy suture.

Complications

Suprabasal Interhemispheric Approach to the Anterior Skull Base

Indications

Position

Surgical Approach

Surgical Approach

Place at least two bur holes perfectly perpendicular on the SSS or on each side of it. Carefully dissect the SSS.

Place at least two bur holes perfectly perpendicular on the SSS or on each side of it. Carefully dissect the SSS.

Make a frontal bone flap between the coronal suture and the frontal sinus according to the size of the lesion. If the lesion is perfectly midline, then the approach can be performed on each side, or, for a right-handed surgeon, more to the right side.

Make a frontal bone flap between the coronal suture and the frontal sinus according to the size of the lesion. If the lesion is perfectly midline, then the approach can be performed on each side, or, for a right-handed surgeon, more to the right side.

Using the microscope, perform interhemispheric dissection along the falx. Stay in the subarachnoid space and avoid going subpial. Identify and preserve the anterior cerebral arteries. Reach the appropriate location along the anterior skull base and the pathology to be treated. Lateral retraction of one of the frontal lobes may be required, but avoid bifrontal retraction at all times.

Using the microscope, perform interhemispheric dissection along the falx. Stay in the subarachnoid space and avoid going subpial. Identify and preserve the anterior cerebral arteries. Reach the appropriate location along the anterior skull base and the pathology to be treated. Lateral retraction of one of the frontal lobes may be required, but avoid bifrontal retraction at all times.

Anterior Approaches to the Skull Base from Below

Transsphenoidal Approach

Sublabial Transsphenoidal Approach

Position of the Head

Apply topical adrenaline with or without local anesthetic or a nasal agent such as xylometazoline, for nasal mucosa vasoconstriction.

Apply topical adrenaline with or without local anesthetic or a nasal agent such as xylometazoline, for nasal mucosa vasoconstriction.

Administer local anesthetic along the floor and the nasal septum in order to assist in the elevation of the flap of mucosal tissue from the sublabial position.

Administer local anesthetic along the floor and the nasal septum in order to assist in the elevation of the flap of mucosal tissue from the sublabial position.

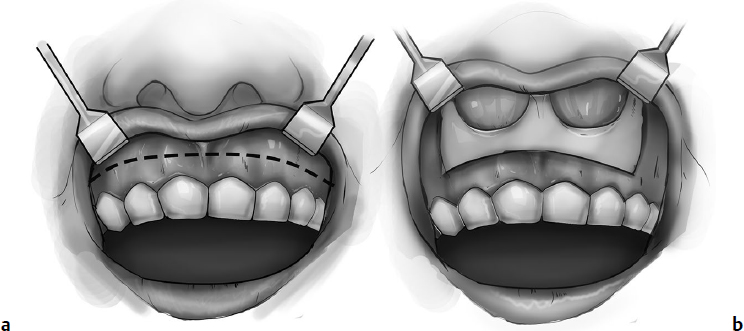

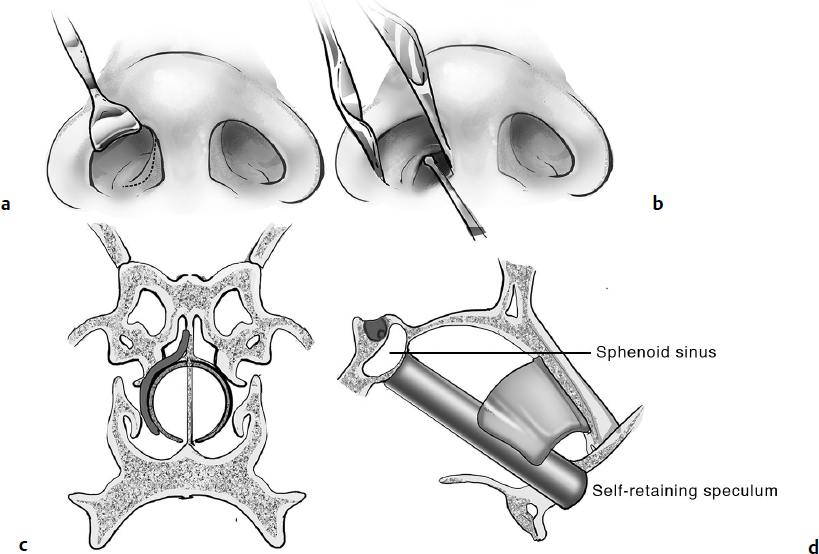

After preparation and elevation of the upper lip, infiltrate local anesthetic with diluted 1:100,000 or 1:200,000 adrenaline, and in a few minutes make a sublabial incision, and elevate the mucosa and periosteum with a dissector to expose the anterior nasal spine and inferior and lateral parts of the piriform aperture, creating one large pocket or two pockets (Fig. 14.4).

After preparation and elevation of the upper lip, infiltrate local anesthetic with diluted 1:100,000 or 1:200,000 adrenaline, and in a few minutes make a sublabial incision, and elevate the mucosa and periosteum with a dissector to expose the anterior nasal spine and inferior and lateral parts of the piriform aperture, creating one large pocket or two pockets (Fig. 14.4).

Elevate the mucosa from the floor of the nasal cavity. Occasionally the spine can be drilled or removed with a small rongeur, but not more than 2 to 3 mm of bone.

Elevate the mucosa from the floor of the nasal cavity. Occasionally the spine can be drilled or removed with a small rongeur, but not more than 2 to 3 mm of bone.

Elevate the mucosa in the anteroposterior direction with a superior and inferior dissection along the septum, reaching the vomer bone, more posteriorly.

Elevate the mucosa in the anteroposterior direction with a superior and inferior dissection along the septum, reaching the vomer bone, more posteriorly.

Separate the mucosa from the perpendicular plate and dissect it from the septal cartilage (columella) on both sides.

Separate the mucosa from the perpendicular plate and dissect it from the septal cartilage (columella) on both sides.

Detach the columella from the vomer bone and perpendicular plate.

Detach the columella from the vomer bone and perpendicular plate.

Insert a nasal speculum and open the blades to straddle the perpendicular plate and expose the sphenoid bone rostrum, and remove it (with rongeurs).

Insert a nasal speculum and open the blades to straddle the perpendicular plate and expose the sphenoid bone rostrum, and remove it (with rongeurs).

Identify the sphenoid ostia and enlarge them as required, to gain access into the sphenoid sinus.

Identify the sphenoid ostia and enlarge them as required, to gain access into the sphenoid sinus.

Strip the sphenoid sinus mucosa and remove the intrasinus septa.

Strip the sphenoid sinus mucosa and remove the intrasinus septa.

Based on the location of the pathology, drill or remove the bone of the sellar floor for access to the pituitary, the tuberculum sellae for access to more superoanterior lesions, and the clivus for posterior fossa approaches.

Based on the location of the pathology, drill or remove the bone of the sellar floor for access to the pituitary, the tuberculum sellae for access to more superoanterior lesions, and the clivus for posterior fossa approaches.

Transnasal Interseptal Approach

Surgical Approach

Surgical Approach

Enlarge the nostril and protect the nasal wing with an elevator or by using a nasal speculum (Fig. 14.5a).

Enlarge the nostril and protect the nasal wing with an elevator or by using a nasal speculum (Fig. 14.5a).

Make a transfixion incision at the muco-squamosal junction just inside the nose along the septum.

Make a transfixion incision at the muco-squamosal junction just inside the nose along the septum.

Elevate the mucosa and perichondrium from the septal cartilage (Fig. 14.5b).

Elevate the mucosa and perichondrium from the septal cartilage (Fig. 14.5b).

Separate the mucosa from the septum on both sides.

Separate the mucosa from the septum on both sides.

Perform luxation of the cartilaginous septum, detaching its posterior attachment on the perpendicular lamina of the ethmoid.

Perform luxation of the cartilaginous septum, detaching its posterior attachment on the perpendicular lamina of the ethmoid.

Introduce a self-retaining speculum between the two septal mucosa layers, open the valves, and reach the floor of the sphenoid sinus.

Introduce a self-retaining speculum between the two septal mucosa layers, open the valves, and reach the floor of the sphenoid sinus.

Open the floor of the sphenoid sinus, connecting the two sphenoid ostia, or drill off the front wall of the sphenoid.

Open the floor of the sphenoid sinus, connecting the two sphenoid ostia, or drill off the front wall of the sphenoid.

Access the sphenoid sinus, strip the mucosa out, and remove the septa, for correct identification of the landmarks.

Access the sphenoid sinus, strip the mucosa out, and remove the septa, for correct identification of the landmarks.

Disadvantages of Microscopic Transsphenoidal Approaches

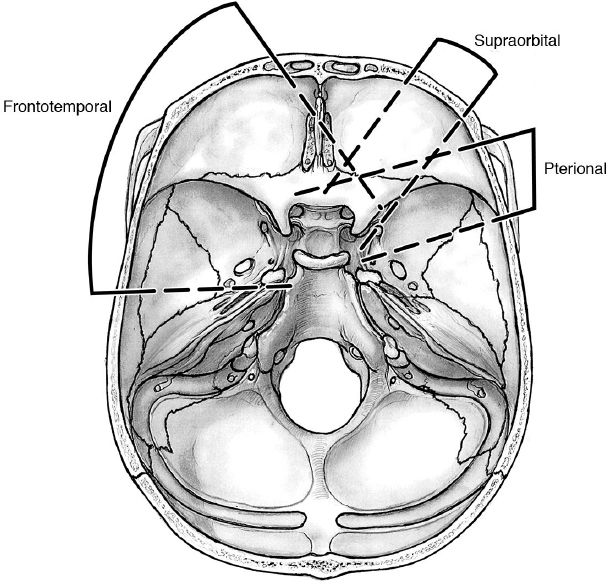

14.3 Anterolateral Approaches

14.3 Anterolateral Approaches

Frontotemporal Craniotomy

Position

Navigation

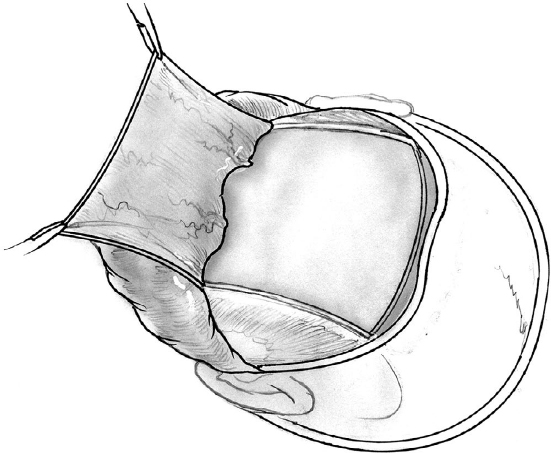

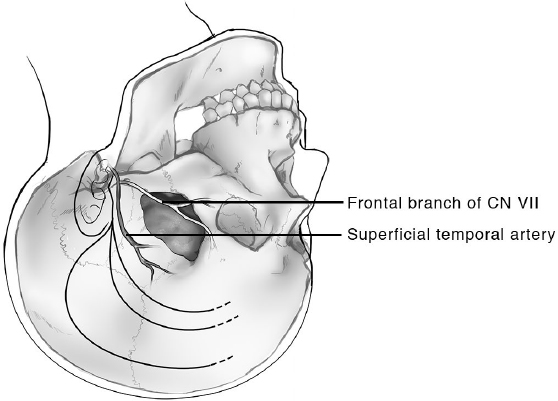

Incision

Scalp Flap

Craniotomy

Middle Fossa Floor

Dural Management

Lesion Management

Reconstruction: Pericranial Flap

Reconstruction: Bone and Soft Tissues

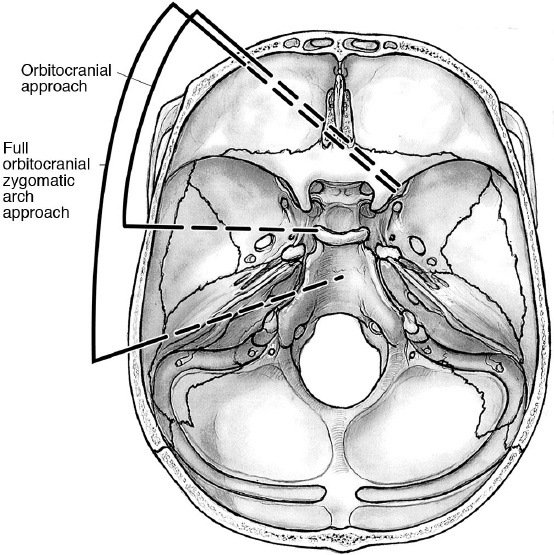

Frontotemporal-Orbitozygomatic Approach

Indications

A variant of the FTOZ approach involving the forced opening of the patient’s mouth has been described for widening the surgical corridor toward the infratemporal space. It can be used for treatment of pathologies both with splanchnoand neurocranial involvement. The forced opening of the mouth keeps the coronoid process of the mandible lower and away from the operating field, providing unobstructed access to the pterygoid and pterygopalatine fossae, and the lateral wall of the maxillary, sphenoid, and ethmoid sinuses, without using a transfacial approach.18

A variant of the FTOZ approach involving the forced opening of the patient’s mouth has been described for widening the surgical corridor toward the infratemporal space. It can be used for treatment of pathologies both with splanchnoand neurocranial involvement. The forced opening of the mouth keeps the coronoid process of the mandible lower and away from the operating field, providing unobstructed access to the pterygoid and pterygopalatine fossae, and the lateral wall of the maxillary, sphenoid, and ethmoid sinuses, without using a transfacial approach.18

For Frontotemporal Craniotomy with Orbitozygomatic Osteotomy

Position

Surgical Approach

Surgical Approach

The incision is made as indicated above. Once the orbital rim is approached, inform the anesthetist because dissection of the periorbita may cause a vasovagal response.

The incision is made as indicated above. Once the orbital rim is approached, inform the anesthetist because dissection of the periorbita may cause a vasovagal response.

Dissect the periosteum along the zygomaticofrontal suture and then closely follow the bone right into the orbit while carefully elevating the periorbita. Always stay right on the bone.

Dissect the periosteum along the zygomaticofrontal suture and then closely follow the bone right into the orbit while carefully elevating the periorbita. Always stay right on the bone.

Avoid use of the monopolar cautery for mobilization of the temporal muscle, instead introduce an elevator in the inferior margin of the posterior incision and elevate the deep fascia from posterior to anterior and from the zygomatic arch to the superior temporal line. This maneuver preserves the innervation and vascularization of the temporal muscle, avoiding postoperative muscle atrophy, cosmetic defects, and swallowing dysfunction.

Avoid use of the monopolar cautery for mobilization of the temporal muscle, instead introduce an elevator in the inferior margin of the posterior incision and elevate the deep fascia from posterior to anterior and from the zygomatic arch to the superior temporal line. This maneuver preserves the innervation and vascularization of the temporal muscle, avoiding postoperative muscle atrophy, cosmetic defects, and swallowing dysfunction.

A meticulous skeletonization of the zygomatic arch from soft tissue makes the osteotomy easier. Free the inferior margin of the arch from the attachment of the masseteric fascia.

A meticulous skeletonization of the zygomatic arch from soft tissue makes the osteotomy easier. Free the inferior margin of the arch from the attachment of the masseteric fascia.

Perform a bone flap by using one to four bur holes. Connect the holes using a craniotome.

Perform a bone flap by using one to four bur holes. Connect the holes using a craniotome.

Variation: You may consider the “bridge technique” for the craniotomy: leave cuts between the bur holes incomplete except for small 2-mm bridges of bone that are cracked free when the bone flap is elevated (see above, page 340).

Variation: You may consider the “bridge technique” for the craniotomy: leave cuts between the bur holes incomplete except for small 2-mm bridges of bone that are cracked free when the bone flap is elevated (see above, page 340).

When the periorbita has been dissected and the zygomatic bone has been fully exposed, incise the temporalis muscle on its posterior margin, and elevate and mobilize it as indicated above.

When the periorbita has been dissected and the zygomatic bone has been fully exposed, incise the temporalis muscle on its posterior margin, and elevate and mobilize it as indicated above.

Orbitozygomatic Osteotomy: Variations

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Dissect the periorbita until reaching the superior and inferior orbital fissures, about 2.5 cm deep. Insert the tip of the dissector (Penfield No. 4, for example) in the fissures. Cottonoids are placed to protect the periorbita during the dissection. When introduced in the inferior orbital fissure (IOF), the tip of the dissector can be seen in the temporal fossa.

Dissect the periorbita until reaching the superior and inferior orbital fissures, about 2.5 cm deep. Insert the tip of the dissector (Penfield No. 4, for example) in the fissures. Cottonoids are placed to protect the periorbita during the dissection. When introduced in the inferior orbital fissure (IOF), the tip of the dissector can be seen in the temporal fossa.