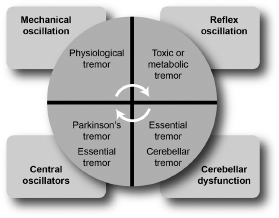

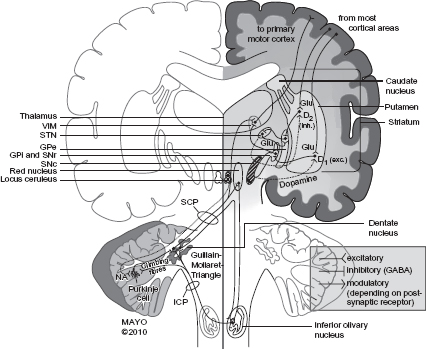

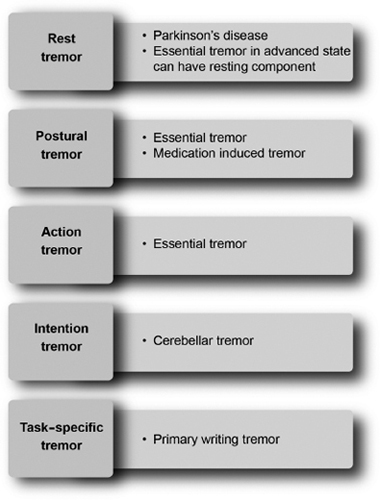

2 TREMORS Tremor is defined as a rhythmic, involuntary, oscillating movement of a body part occurring in isolation or as part of a clinical syndrome. In clinical practice, characterization of tremor is important for etiologic consideration and treatment. Common types include resting tremor, postural tremor, kinetic tremor, intention tremor, and task-specific tremor. The pathophysiology of tremor is not fully understood. However, four basic mechanisms are linked to the production of tremor.1,2 It is likely that combinations of these mechanisms produce tremor in different disease states (Figure 2.1). Two neuronal pathways are of particular importance in the production of tremor (Figure 2.2).4 Figure 2.1 Figure 2.2 From Ref. 4: Puschmann A, Wszolek ZK. Diagnosis and treatment of common forms of tremor. Semin Neurol 2011;31(1), 65–77, with permission. Figure 2.3 POSTURAL TREMOR. Postural tremor occurs when the affected limb is held in sustention against gravity. ACTION OR KINETIC TREMOR. Action or kinetic tremor occurs during voluntary movement. INTENTION TREMOR. Intention (or terminal) tremor manifests as a marked increase in tremor amplitude during the terminal portion of a targeted movement. TASK-SPECIFIC TREMOR. Task-specific tremor emerges during a specific activity. An example of this type is primary writing tremor. Table 2.1 Diagnosis Predominant Tremor Remarks Parkinson’s disease Resting Associated symptoms include rigidity, bradykinesia, and postural instability. Usually an elderly patient (> 50 y) with asymmetric onset, 4–6 Hz. Essential tremor Postural and kinetic Usually symmetric, responds to alcohol, bimodal age at onset (teens, > 50 y), 4–10 Hz. Cerebellar tremor Intention Postural component may be present, other cerebellar features on examination. Unilateral or bilateral depending on location of lesion, 2–4 Hz. Holmes tremor Rest, postural, and intention Seen in multiple sclerosis and traumatic brain injury, 2–5 Hz. Dystonic tremor Postural and intention Abnormal posture of affected limb may be observed, variable frequency, 4–8 Hz. Enhanced physiologic tremor Postural Check for metabolic disorders (thyroid, diabetes, renal failure, liver disease) or tremor-inducing drugs, 8–12 Hz. Orthostatic tremor Postural, in the legs, upon standing Usually occurs when patient stands up, improves with ambulation and sitting, 15–18 Hz. Palatal tremor Postural 1–6 Hz. Neuropathic tremor Postural and kinetic In association with neuropathy, 5–9 Hz. Wilson’s disease Resting, postural, or action All tremor types are possible; “wing-beating tremor” usually manifests later. Should be considered in any movement disorder in a patient < 50 y. Physiologic tremor is a very-low-amplitude, fine tremor (6–12 Hz) that is barely visible to the eye. Enhanced physiologic tremor is a high-frequency, low-amplitude, visible tremor that occurs primarily when a specific posture is maintained. Parkinson tremor (see also Chapter 4 and Table 2.2) is often characterized by a low-frequency resting tremor typically seen as a pill-rolling tremor. Some patients may have postural and action tremors as well. Resting tremors may also be observed in other parkinsonian syndromes. Table 2.2 Characteristic Essential Tremor Parkinson Tremor Tremor type Postural and action tremors Resting tremor Age All age groups Older age (> 60 y) Family history Positive in > 60% of patients Usually negative Alcohol response Often beneficial Not beneficial Tremor onset Usually bilateral Unilateral in about 80% Muscle tone Normal Cogwheel rigidity Facial expression Normal Decreased Gait Normal Decreased arm swing Tremor latency during hand sustention None or shorter: 1–2 sec Longer, sometimes up to 8–9 sec Essential tremor (ET) (Table 2.2) is the most common type of tremor disorder in the general population. Cerebellar tremor is a slow-frequency tremor, between 3 and 5 Hz. It occurs during the execution of a goal-directed (intentional) movement. Unfortunately, these tremors are highly disabling and very difficult to treat. Holmes tremor or rubral tremor designates a combination of rest, postural, and action tremors due to midbrain lesions in the vicinity of the red nucleus.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Mechanical oscillations of the limb can occur at a particular joint; this mechanism applies in cases of physiologic tremor.

Mechanical oscillations of the limb can occur at a particular joint; this mechanism applies in cases of physiologic tremor.

Reflex oscillation is elicited by afferent muscle spindle pathways and is responsible for stronger tremors by synchronization. This mechanism is a possible cause of tremor in hyperthyroidism or other toxic states.

Reflex oscillation is elicited by afferent muscle spindle pathways and is responsible for stronger tremors by synchronization. This mechanism is a possible cause of tremor in hyperthyroidism or other toxic states.

Central oscillators are groups of cells in the central nervous system in the thalamus, basal ganglia, and inferior olives. These cells have the capacity to fire repetitively and produce tremor. Parkinsonian tremors may originate in the basal ganglia, and essential tremors may originate within the inferior olives and thalamus.

Central oscillators are groups of cells in the central nervous system in the thalamus, basal ganglia, and inferior olives. These cells have the capacity to fire repetitively and produce tremor. Parkinsonian tremors may originate in the basal ganglia, and essential tremors may originate within the inferior olives and thalamus.

Abnormal functioning of the cerebellum can produce tremor. Positron emission tomography studies have shown cerebellar activation in almost all forms of tremor.3

Abnormal functioning of the cerebellum can produce tremor. Positron emission tomography studies have shown cerebellar activation in almost all forms of tremor.3

Pathophysiology of different etiologies of tremor.

Schematic and simplified synopsis of the brain regions and pathways involved in tremorogenesis. See text for details. D1, dopamine receptor type 1; D2, dopamine receptor type 2; exc., excitatory; GABA, gamma-amino butyric acid; Glu, glutamate; GPe, external globus pallidus; GPi, internal globus pallidus; ICP, inferior cerebellar peduncle; inh., inhibitory; SCP, superior cerebellar peduncle; SNc, substantia nigra, pars compacta; SNr, substantia nigra, pars reticulata; STN, subthalamic nucleus; VIM, ventrointermediate nucleus of thalamus.

The other pathway connects the red nucleus, inferior olivary nucleus, and dentate nucleus, forming the “Guillain-Mollaret triangle.” This pathway is involved in fine-tuning the precision of voluntary movements.

The other pathway connects the red nucleus, inferior olivary nucleus, and dentate nucleus, forming the “Guillain-Mollaret triangle.” This pathway is involved in fine-tuning the precision of voluntary movements.

CLASSIFICATION (Figure 2.3)

Classification of tremors.

CLINICAL DISORDERS (Table 2.1)

Tremor Characteristics by Condition

Physiologic Tremor

It is present in every normal person while a posture or movement is being maintained.

It is present in every normal person while a posture or movement is being maintained.

The neurological examination is often nonfocal in patients with physiologic tremor.

The neurological examination is often nonfocal in patients with physiologic tremor.

Enhanced Physiologic Tremor

Drugs and toxins induce this form of tremor. The suspected mechanism is mechanical activation at the muscular level. Signs and symptoms of drug toxicity or other side effects may or may not be present.

Drugs and toxins induce this form of tremor. The suspected mechanism is mechanical activation at the muscular level. Signs and symptoms of drug toxicity or other side effects may or may not be present.

Trigger conditions include hyperthyroidism, liver disease, benzodiazepine withdrawal, lithium, valproate, calcium channel blockers, anxiety, and hypoglycemia, among other conditions.

Trigger conditions include hyperthyroidism, liver disease, benzodiazepine withdrawal, lithium, valproate, calcium channel blockers, anxiety, and hypoglycemia, among other conditions.

Tremor symptoms can improve after the discontinuation of the causative agents or management of the underlying problem.

Tremor symptoms can improve after the discontinuation of the causative agents or management of the underlying problem.

Parkinson’s Disease

Parkinson tremors occur in association with other symptoms, such as micrographia, slowness (bradykinesia), and muscle rigidity.

Parkinson tremors occur in association with other symptoms, such as micrographia, slowness (bradykinesia), and muscle rigidity.

A characteristic feature of the symptoms in Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the asymmetric nature of the symptoms, especially early in the disease.

A characteristic feature of the symptoms in Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the asymmetric nature of the symptoms, especially early in the disease.

The characteristic frequency associated with this tremor is 4 to 6 Hz. Tremors can emerge during posture (reemergent tremor when it occurs a few seconds after the hands have been held in sustention) and action.

The characteristic frequency associated with this tremor is 4 to 6 Hz. Tremors can emerge during posture (reemergent tremor when it occurs a few seconds after the hands have been held in sustention) and action.

The areas most commonly affected include the hands, legs, chin, and jaw.

The areas most commonly affected include the hands, legs, chin, and jaw.

Patients sometimes complain of the sensation of “internal tremors” that are not visible externally.

Patients sometimes complain of the sensation of “internal tremors” that are not visible externally.

Characteristics of Parkinsonian Versus Essential Tremor

Essential Tremor

The characteristic tremors seen in ET are postural and action tremors, with a frequency between 4 and 8 Hz. Most patients have a symmetric onset of their tremor.

The characteristic tremors seen in ET are postural and action tremors, with a frequency between 4 and 8 Hz. Most patients have a symmetric onset of their tremor.

In familial ET, the mode of inheritance is autosomal dominant, with incomplete penetrance.

In familial ET, the mode of inheritance is autosomal dominant, with incomplete penetrance.

A positive family history is reported by 50% to 70% of patients with ET.

A positive family history is reported by 50% to 70% of patients with ET.

The tremor worsens during eating, drinking, and writing.

The tremor worsens during eating, drinking, and writing.

Drinking alcohol may temporarily help to alleviate ET.

Drinking alcohol may temporarily help to alleviate ET.

The most hands, head, and voice are most commonly affected, but tremors can also be seen in the legs, trunk, and face.

The most hands, head, and voice are most commonly affected, but tremors can also be seen in the legs, trunk, and face.

Mild resting tremor can sometimes develop in patients with long-standing ET.

Mild resting tremor can sometimes develop in patients with long-standing ET.

The tremor in ET is exacerbated by conditions such as stress, exercise, fatigue, caffeine, and certain medications, and it improves with relaxation and alcohol.

The tremor in ET is exacerbated by conditions such as stress, exercise, fatigue, caffeine, and certain medications, and it improves with relaxation and alcohol.

Other associated symptoms can include mild gait difficulty, manifested as tandem walking.

Other associated symptoms can include mild gait difficulty, manifested as tandem walking.

Some patients with ET have decreased hearing.

Some patients with ET have decreased hearing.

Several tremor conditions are believed to be variants of essential tremor, including the following:

Several tremor conditions are believed to be variants of essential tremor, including the following:

Task-specific tremor (eg, primary writing tremor)

Task-specific tremor (eg, primary writing tremor)

Isolated voice tremor

Isolated voice tremor

Isolated chin tremor

Isolated chin tremor

Cerebellar Tremor

The amplitude usually increases with the movement and as the intended target is approached, and the tremor can be associated with a postural component.

The amplitude usually increases with the movement and as the intended target is approached, and the tremor can be associated with a postural component.

Signs and symptoms of cerebellar dysfunction may be present, including ataxia, dysmetria, dysdiadochokinesia, and dysarthria.

Signs and symptoms of cerebellar dysfunction may be present, including ataxia, dysmetria, dysdiadochokinesia, and dysarthria.

Another tremor with a cerebellar etiology is titubation, better described as a slow-frequency “bobbing” motion of the head or trunk.

Another tremor with a cerebellar etiology is titubation, better described as a slow-frequency “bobbing” motion of the head or trunk.

It is usually seen in conditions such as multiple sclerosis, hereditary ataxia syndromes, brainstem stroke affecting cerebellar pathways, and traumatic brain injury.

It is usually seen in conditions such as multiple sclerosis, hereditary ataxia syndromes, brainstem stroke affecting cerebellar pathways, and traumatic brain injury.

Holmes Tremor

This type of tremor is irregular and of low frequency (2–4 Hz).

This type of tremor is irregular and of low frequency (2–4 Hz).

Signs of ataxia and weakness may be present.

Signs of ataxia and weakness may be present.

Common causes include cerebrovascular accident and multiple sclerosis, with a possible delay of 2 weeks to 2 years in tremor onset and the occurrence of lesions.

Common causes include cerebrovascular accident and multiple sclerosis, with a possible delay of 2 weeks to 2 years in tremor onset and the occurrence of lesions.

The tremor is disabling and resistant to treatment.

The tremor is disabling and resistant to treatment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree