CHAPTER 102 TUMORS OF THE PERIPHERAL NERVES

The peripheral nervous system is affected by neoplastic disease in the following ways:

Tumors of the peripheral nerves (PNTs) are sufficiently common that they are encountered by surgeons or neurologists at regular intervals but infrequently enough to still cause perplexity in diagnosis and treatment. Too many cases of benign schwannoma are subjected to biopsy, which damages the parent nerve, inflicts pain, and increases the difficulties surrounding excision; too often the true nature of the swelling and of its anatomical relations is not appreciated, so that the nerve trunk is excised. Even worse, inadequate biopsy or incorrect interpretation of that biopsy in a malignant tumor of nerve leads to inadequate treatment.1

The classification used in this chapter is displayed in Table 102-1. The true nature of PNT has been greatly clarified by electron microscopy, immunohistochemistry, and genetic studies. Perineurial cells arise from fibroblasts.2 Transmission electron microscopic studies have shown that schwannomas do indeed arise from Schwann cells; ultrastructural characteristics enable the distinction among schwannoma, neurofibroma, and perineurioma.3 Folpe and Gowan4 emphasized the role of immunocytochemistry in the analysis of PNT, whereby specific antigens on cells of neural origin can be demonstrated by polyclonal or monoclonal antibodies. The strong expression of S-100 by Schwann cells is particularly important in distinguishing between the large schwannomas of the retroperitoneum and soft tissue sarcomas. The perineurial cell does not express S-100 but does express the epithelial membrane antigen. Fibroblasts express vimentin and fibromentin. Immunoreactivity, cytogenetic, and molecular genetic analyses demonstrate that Ewing’s sarcoma, Askin’s tumor of the chest wall, the primitive neuroectodermal tumor of bone, and neuroepithelioma are variations from a common neural origin, distinct from neuroblastoma. The cells of Ewing’s sarcoma exhibit characteristic reciprocal translocation of the long arms of chromosomes 11 and 21, in common with other tumors of this group.5–8

TABLE 102-1 Classification of Peripheral Nerve Tumors

| Type | Benign | Malignant |

|---|---|---|

| Nerve sheath tumors | Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) (malignant schwannoma, neurofibrosarcoma, nerve sheath sarcoma) | |

| Neural tumors | Ganglioneuroma |

The clinical diagnosis of most PNTs, whether benign or malignant, is usually fairly straightforward in cases in which the swelling is located within the limbs. Supplementary investigations are necessary to confirm that diagnosis and to clarify the location of the tumor, its size, and its relation to vital structures. The possibility of a second malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) or of premalignant change within a benign lesion is a particular problem in NF1. A swelling of a nerve may masquerade as PNT and yet may, in fact, be an expression of generalized neuropathy (Figs. 102-1 and 102-2).

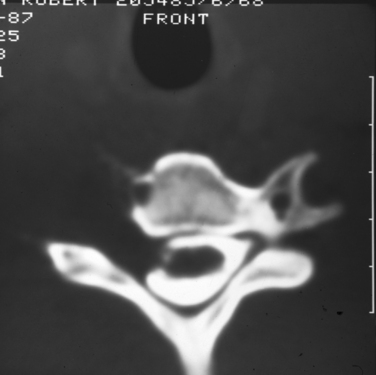

Plain radiographs of the affected anatomy should always be obtained before any computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. For most PNTs, magnetic resonance imaging is particularly valuable in showing the relations of the tumor and in indicating the extent of spread into the skeleton or spinal canal.9 Magnetic resonance angiography is probably superior to digital subtraction angiography in demonstrating the relation of the tumor to adjacent great vessels. Computed tomography with contrast enhancement is required in the analysis of tumors extending within the spinal canal (Fig. 102-3).

BIOPSY

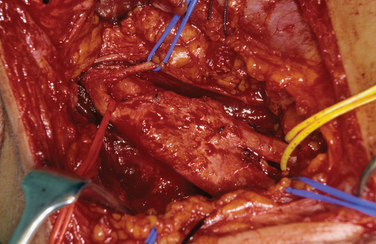

Biopsy should not be performed when the clinical diagnosis of benign PNT is secure. There are some objections to biopsy in MPNST: The intervention must breach tissue planes; an inadequate sample or incorrect analysis may lead to a false diagnosis of benign lesion in MPNST or of malignancy within a benign lesion. A biopsy specimen in MPNST should be adequate for defining the cell of origin, and this is particularly relevant in primitive neuroectodermal tumors, for which adjuvant therapy is an essential element in treatment. The staging of sarcomas of bone or of other soft tissues is a well-established and accepted practice. However, the compartment for an MPNST is the trunk nerve itself, and the authors have found centripetal extension of up to 20 cm within an apparently normal nerve trunk in some cases. Conventional staging investigations do not detect early malignancies at other sites in NF1, nor are they particularly good in detecting the early stages of transformation from benign to malignant lesions. MPNSTs are best treated in units that have access to all essential modalities of diagnosis. The operating surgeon should be responsible for the planning of biopsy and also for examination of all and of any material with colleagues in a multidisciplinary team (Fig. 102-4).

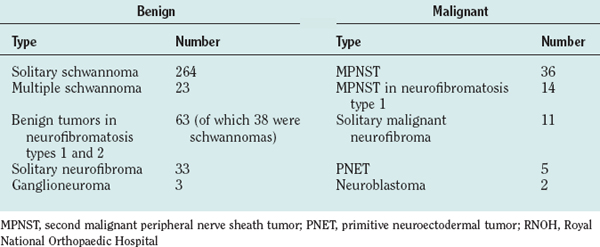

The authors’ unit has treated more than 450 patients with PNTs (Table 102-2). Their experience and those of others in the management of these tumors are summarized as follows.

THE BENIGN SCHWANNOMA

This is the most common of all true PNTs, and it can be removed without impairment for function of the nerve of origin. Eighty percent of affected patients were between 30 and 69 years of age; 55% were male. The upper limb was the site of the tumor in more than 70% of cases; the brachial plexus and adjacent spinal nerves, in a little more than one third. Schwannomas can be found in bone, muscle, or viscera. Massive mediastinal or retroperitoneal tumors are not rare. The authors have found multiple schwannomas in 23 patients, and the tumor is common in NF1. Loss of function occurs when the tumor arises in an enclosed space. Most intraspinal/extraspinal tumors (dumbbell tumors) are schwannomas, and affected patients may present with quite advanced afflictions of the spinal cord. Bilateral vestibular tumors are pathognomonic of neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2). Schwannomas arise from Schwann cells, which invest cranial nerves III to XII close to their origin. Malignant transformation of a benign schwannoma is rare.10

Pathology

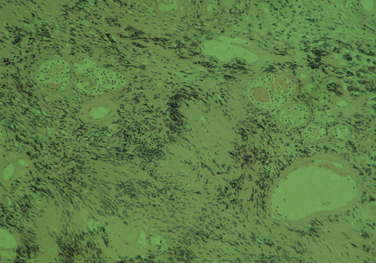

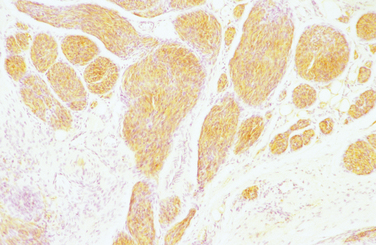

The diagnostic feature is the organization of Schwann cells into areas of compact bundles (Antoni-A tissue) or a less orderly arrangement of spindle or oval cells in a loose matrix (Antoni-B tissue). There may be an abrupt change from one to the other. Palisades of compact parallel rows of cells forming Verocay bodies are a feature of Antoni-A tissue. In larger tumors, the nuclei may appear hyperchromatic, large, and multilobed (ancient schwannomas) and a misdiagnosis of malignancy may be made on the basis of these findings, as it may also be for schwannomas formed exclusively from Antoni-A tissue (the cellular variety). This error is prevented by consideration of the nature of the tumor as a whole and by immunohistochemistry. Strong expression of S-100 distinguishes the schwannoma from soft tissue sarcomas such as leiomyosarcoma (Figs. 102-5 and 102-6).11

Figure 102-6 Cellular plexiform schwannoma showing strong S-100 staining. Magnification, ×100.

(Courtesy of Dr. Jean Pringle, Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree