CHAPTER 99 TUMORS OF THE SPINAL CORD

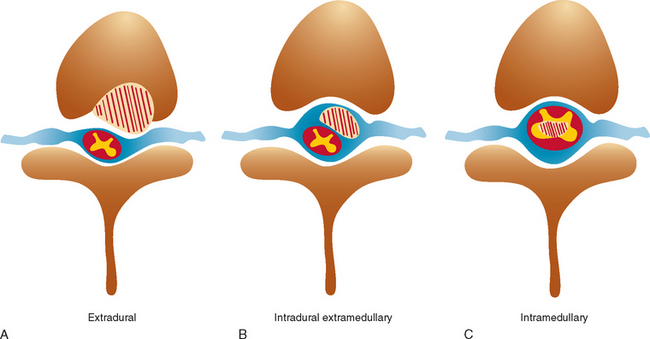

Tumors of the spinal cord are a rare but distinct group of central nervous system neoplasms that affect all ages. Often slow growing, they should be considered in any patient who presents with neck or back pain, radiculopathy, or myelopathy. Classification is based on location and cell of origin: Intramedullary tumors most often arise from glial cells; intradural extramedullary tumors may arise from Schwann cells of the nerve roots or meningeal cells covering the spinal cord; and extradural tumors commonly arise from the bony elements of the vertebral column. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) plays a central role in anatomical localization and diagnosis. Since the first resection of a spinal cord tumor by Victor Horsley in 1887, advances in microsurgical techniques have allowed physicians to more accurately diagnose and treat spinal cord tumors. However, much remains to be learned about optimal management for this rare but challenging group of neoplasms.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

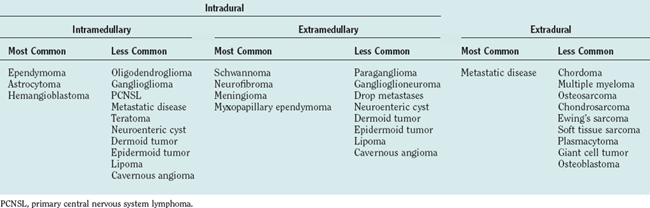

Spinal cord tumors are rare, accounting for only 4% to 10% of all primary central nervous system tumors. According to several population-based studies, their annual incidence is estimated to be 0.5 to 1.4 per 100,000.1,2 Spinal cord tumors are classified into three groups according to anatomical location: extradural, intradural extramedullary, and intramedullary (Fig. 99-1).

Figure 99-1 Anatomical location of spinal cord tumors. A, Extradural. B, Intradural extramedullary. C, Intramedullary.

Intradural extramedullary tumors represent more than half of the nonextradural spinal cord tumors in adults. Approximately 80% of these tumors are either nerve sheath tumors (neurofibromas and schwannomas) or meningiomas; epidermoids, dermoids, teratomas, and metastases make up much of the remaining fraction (Table 99-1). Nerve sheath tumors most commonly manifest in the fourth decade and are evenly distributed among men and women. Multiple intraspinal neurofibromas are often found in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1. Malignant degeneration of a neurofibroma into a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor is a rare but highly lethal complication in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1. Spinal meningiomas most often manifest in the fifth to seventh decades and exhibit a striking female predilection (4 : 1). In women, 80% occur in the thoracic spine. This regional predominance does not hold true in men, in whom meningiomas are found throughout the cervical, thoracic, and, less commonly, lumbosacral cord. Ionizing radiation and trauma are known risk factors for the development of spinal meningiomas.3

Intramedullary tumors account for less than one third of all spinal tumors in adults, whereas the majority of spinal tumors in children are intramedullary.4 Glial tumors (ependymomas and astrocytomas) predominate in all age groups. Ependymomas are increasingly more common with age, reaching a peak incidence in the fourth decade. They occur more frequently in men than in women. The remainder of the category is composed of rare tumors such as hemangioblastoma, neurocytoma, ganglioglioma, lipoma, primitive neuroectodermal tumor, lymphoma, and metastatic disease. Hemangioblastomas also exhibit a male preponderance and may occur sporadically or in association with von Hippel–Lindau disease. Gangliogliomas, although rare in adults, have been recognized as among the most common intramedullary tumors in children.5

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Pain from spinal cord tumors manifests in several different forms. Most commonly, patients experience midline or axial spinal pain. It is often worse at night and increased with recumbency, coughing, sneezing, straining, or other maneuvers that increase intrathoracic or intra-abdominal pressure. Paraspinal pain and tenderness may also be present as a result of local muscle spasm. Pain and dysesthesias that follow a radicular distribution are most common with extramedullary lesions that affect the dorsal roots or plexus; painful dysesthesias affecting an entire limb have also been described. A sensation of lancinating pain or electricity down the length of the spine, Lhermitte’s sign, can be caused by compressive cervical cord lesions. Thoracic tumors may cause a bandlike pain around the chest or abdomen, resembling the pain of herpetic neuralgia. Tumors in this location may also cause progressive kyphoscoliosis, particularly in children.6

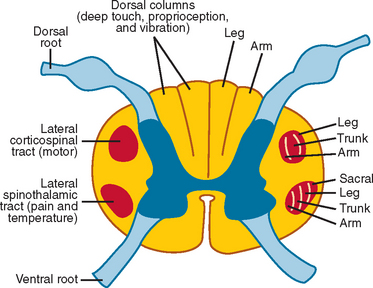

Weakness, reflex change, sensory loss, and bowel or bladder dysfunction may be present early or late in the course of disease. Intramedullary lesions tend to produce dysfunction earlier than do extramedullary lesions, which often cause deficits by external compression rather than direct invasion of tissue. In general, rapid progression or short duration of symptoms portends a higher grade tumor and a poorer prognosis.7,8 Weakness from spinal cord tumors may be secondary to (1) direct involvement of the anterior horn cells or descending motor tracts within the cord itself, as with intramedullary tumors; (2) compression or infiltration of the ventral roots as they exit the spinal cord, as with nerve sheath tumors; or (3) external compression of the corticospinal tracts, resulting in myelopathy and upper motor neuron weakness, as with many extramedullary tumors, particularly thoracic meningiomas or epidural metastases.9 Sensory loss is often patchy, involving one or more particular modalities more than others. For example, central cord lesions, such as ependymomas, can cause pain and loss of temperature sensation with preserved position and vibratory sensation by affecting the central crossing fibers in the cord. Because of lamellation of the spinothalamic tracts, there may be sacral sparing of pain and temperature sensation from central lesions as well (Fig. 99-2). Compressive lesions often manifest with pain and an ascending sensory level; accompanying signs may include spasticity, upper motor neuron weakness, and bladder dysfunction. In general, sensory loss from intramedullary cord lesions tends to be symmetrical, whereas sensory loss from extramedullary lesions is often asymmetrical as a result of involvement of nerve roots.

Several well-recognized syndromes may be encountered from spinal cord tumors at various levels. Tumors in the lower lumbar region may produce a conus medullaris syndrome, characterized by early bowel, bladder, and sexual dysfunction; by a mixture of upper and lower motor neuron weakness; and by patchy numbness. Tumors in this region can also produce a cauda equina syndrome, characterized by urinary retention, saddle anesthesia, lower motor neuron weakness, and reflex loss. Brown-Séquard syndrome—with ipsilateral weakness; contralateral pain; and loss of proprioception, vibration sensation, and temperature sensation—can result from eccentric intramedullary or extramedullary lesions. Tumors at the foramen magnum can cause suboccipital pain, lower cranial nerve palsies, bilateral hand atrophy, and loss of position and vibration sensation in the upper extremities more than in the lower extremities. Finally, hydrocephalus can be present in association with spinal cord tumors, particularly those in the high cervical region, perhaps as a result of high cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) protein level, spinal block, or outflow obstruction of the fourth ventricle caused by leptomeningeal thickening.10

The differential diagnosis of spinal cord tumors includes (1) nonneoplastic or dysembryonic lesions, such as lipoma or syringomyelia; (2) vascular malformations, including arterial venous malformation and dural arteriovenous fistula; (3) vascular disease, such as spinal cord infarction or amyloid angiopathy11; (4) demyelinating disease; (5) inflammatory myelitis, as in transverse myelitis or sarcoidosis; (6) infectious disease, including syphilis, human T cell lymphotropic virus type 1, and schistosomiasis; (7) neurodegenerative disease, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; and (8) extrinsic compression from degenerative joint disease, as in spondylosis or hypertrophic arthritis, epidural metastatic disease, extramedullary hematopoiesis, and epidural lipomatosis (Table 99-2).

TABLE 99-2 Differential Diagnosis of Spinal Cord Tumor

| Dysembryonic lesions | Lipoma |

| Neuroenteric cyst | |

| Dermoid tumor | |

| Epidermoid tumor | |

| Vascular malformations | AVM |

| Dural AVF | |

| Vascular disease | Spinal cord stroke |

| Amyloid angiopathy | |

| Demyelinating disease | Multiple sclerosis |

| Inflammatory disease | Transverse myelitis |

| Sarcoidosis | |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | |

| Infectious disease | Syphilis |

| Tuberculosis | |

| HTLV-1 | |

| Schistosomiasis | |

| Degenerative joint disease | Cervical spondylosis |

| Hypertrophic arthritis | |

| Herniated disc | |

| Neurodegenerative disease | ALS |

| Miscellaneous | Post-irradiation myelopathy |

| Syringomyelia | |

| Epidural lipomatosis | |

| Extramedullary hematopoiesis |

ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; AVF, arteriovenous fistula; AVM, arteriovenous malformation; HTLV-1, human T cell lymphotrophic virus type 1.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

Computed Tomography and Computed Tomographic Myelography

Like the plain radiograph, computed tomography (CT) has largely been supplanted by MRI except in patients who cannot tolerate or who have a contraindication to MRI. CT does remain the study of choice for visualization of osseous structures and can demonstrate bony changes surrounding an extramedullary mass in the region of the neural foramen. CT is also useful during preoperative planning to evaluate spinal stability. Intravenous contrast material enhances the sensitivity of CT for detecting soft tissue pathology if MRI cannot be performed. For tumors in the cervical region, computed tomographic angiography may be employed to define the relationship of the tumor with the vertebral arteries. Computed tomographic myelography is superior to standard myelography for demonstrating the rounded filling defects of intradural extramedullary lesions or widening of the spinal cord caused by intramedullary lesions.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI plays a central role in the imaging of spinal cord tumors and affords superior anatomical localization of soft tissue masses. The majority of tumors can easily be classified as extradural, intradural extramedullary, or intramedullary by MRI alone; this thereby greatly aids in characterization of the tumor. Both sagittal and axial T1- and T2-weighted images should be obtained, in addition to sagittal and axial T1-weighted images after the administration of gadolinium. Diffusion-weighted imaging is occasionally useful for detecting cytotoxic edema and for differentiating tumors from abscesses.12

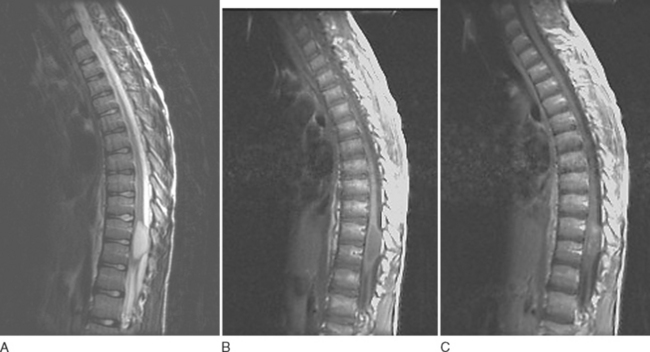

Astrocytomas usually manifest as focal enlargements of the spinal cord (Fig. 99-3). They are typically hypointense or isointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted images. Unlike their intracranial counterparts, nearly all spinal astrocytomas are enhanced after administration of contrast material, regardless of World Health Organization grade. Contrast material helps delineate tumor margins from surrounding edema, cyst, or syrinx. Although both cysts and syrines are hyperintense on T2-weighted images, cysts usually show enhancement along their borders, whereas syrinxes do not.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree