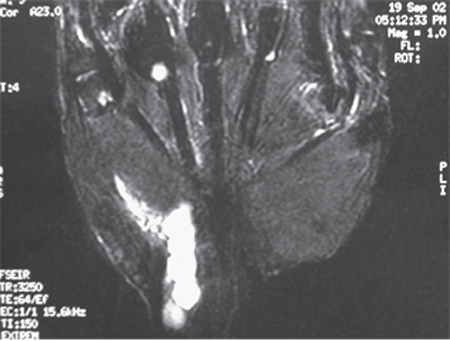

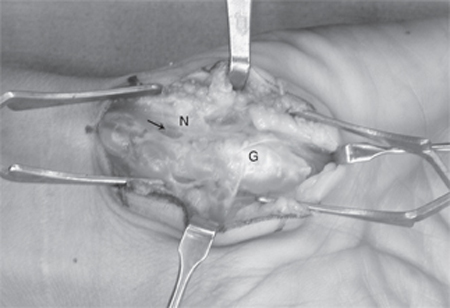

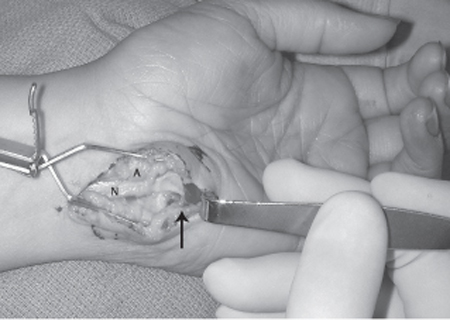

28 Ulnar Nerve Compression—Guyon Canal A 30-year-old female presented to her primary care physician with the chief complaint of numbness and tingling in her small and ring fingers for 2 months’ duration. The symptoms were worse while she was working behind the meat counter. She stated that her hand felt weak and she had trouble generating a tight grip. She was referred to a surgeon for evaluation of possible cubital tunnel syndrome and was sent for a nerve conduction study with electromyography. More recently she noted swelling in the wrist. On physical examination there was a 1 cm by 4 cm area of swelling at the hypothenar base, extending proximally. This mass was nonpulsatile. Compression over the ulnar aspect of the wrist reproduced tingling in her two ulnar fingers. She had slightly diminished grip strength on the symptomatic side. An Allen test revealed patent radial and ulnar arteries with an incomplete superficial arch. The remainder of her physical exam was normal at the wrist and elbow. Nerve conduction studies demonstrated compression of the ulnar nerve at the wrist only. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a multiloculated ganglion (Fig. 28–1). An ulnar tunnel exploration was performed, which revealed an elongated ganglion arising directly from the flexor carpi ulnaris tendon sheath with adhesions to the ulnar nerve and artery (Fig. 28–2). After complete mobilization of the nerve and artery, the ganglion was completely excised. She returned to work, using a deli slicer, at 3 weeks postsurgery. Hand therapy, including desensitization and scar management, was prescribed for incisional hypersensitivity. She experienced gradual resolution of her paresthesias with near normal grip strength. Compressive neuropathy of the ulnar nerve at the Guyon canal (ulnar tunnel syndrome) due to a ganglion Figure 28–1 Magnetic resonance imaging of the wrist and hand, demonstrating longitudinal, multiloculated ganglion that is displacing the ulnar nerve medially. The ulnar nerve arises from the medial cord of the brachial plexus (nerve roots C8 and T1). It runs along the medial aspect of the axillary artery, pierces the medial intermuscular septum ˜8 cm proximal to the medial epicondyle, and then travels on the medial triceps. The ulnar nerve passes posterior to the medial epicondyle, running deep to the arcuate ligament (within the cubital tunnel) before entering the forearm between the two heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle. Below the elbow it gives off branches to the flexor carpi ulnaris and the ulnar half of the flexor digitorum profundus. It then runs under cover of the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle throughout the forearm. Proximal to the wrist the dorsal sensory branch of the ulnar nerve becomes subcutaneous ˜5 cm proximal to the pisiform. This branch supplies sensation to the dorsal ulnar hand and ulnar 1½ digits proximal to the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint. As the ulnar nerve traverses the wrist it lies on the ulnar aspect of the ulnar artery. It crosses radial to the pisiform to enter the Guyon canal. Figure 28–2 Intraoperative view of the wrist ganglion (G) causing compression of the ulnar nerve (N) and artery (arrow). The roof of the Guyon canal is formed by the volar (palmar) carpal ligament. It does not attach to the hook of the hamate as previously thought but to the flexor retinaculum or transverse carpal ligament, which allows the ulnar artery and sensory branch to sometimes present radial to the hook of the hamate. The transverse carpal ligament forms the floor of the canal, with the pisiform and the hook of the hamate forming the medial and lateral borders, respectively. The distal ulnar tunnel can be divided into three zones, which explains the variations in clinical presentations. Zone 1 is proximal to the bifurcation of the ulnar nerve into sensory and motor branches. This zone begins at the proximal edge of the volar carpal ligament and runs for 2 to 3 cm. Zone 2 envelops the deep motor branch, which supplies the hypothenar muscles, the third and fourth lumbricales, the adductor pollicis, the deep head of the flexor pollicis brevis, and all interossei muscles. Zone 3 surrounds the superficial branch, which supplies the palmaris brevis and the palmar skin of the small finger and ulnar half of the ring finger. Ulnar tunnel syndrome typically presents with one of three variations. Symptoms may be purely motor, purely sensory, or mixed, depending on the location of entrapment or compression. Compression in zone 1 causes mixed sensory and motor deficits. Sensory complaints consist of numbness and paresthesias in the small and ring fingers. Motor weakness causes hand clumsiness and weakness in pinch and grip. Compression in zone 2 causes purely motor deficits, and compression in zone 3 causes purely sensory symptoms. Patients typically present with numbness, tingling, or paresthesias in the small and ring fingers. Pain, however, is not a common feature. Symptoms may be reproduced with provocative tests, including percussion of the ulnar nerve (Tinel sign), compression along and just proximal to the Guyon canal, and with Phalen and reverse Phalen test (maximal wrist flexion and extension, respectively, for 1 minute). In mild to moderate cases, abnormal vibratory thresholds or Semmes-Weinstein monofilament testing is the most sensitive indicator of changes in sensibility. With more advanced neuropathy, an increased distance in two-point discrimination (normal ≤ 6 mm) can help to determine the pattern of sensory loss in the fingers. These sensibility tests may also assist in diagnosing concomitant carpal tunnel syndrome or peripheral neuropathy. Weakness in grip strength, small finger abduction, thumb adduction, and the interossei will be present in more advanced disease. Wartenberg sign, Froment paper sign, and crossed-finger test will be positive with significant intrinsic weakness or atrophy. These physical findings, as well as nerve conduction studies, may aid in localizing the level of ulnar nerve compression. Ganglia may be found on physical exam. Fractures and nonunions of the hook of the hamate should be suspected in anyone with a recent or remote history of trauma and continued pain. Pain or point tenderness in the palm (rarely seen in idiopathic ulnar tunnel syndrome) may be associated with such fractures. Reduction in the radial pulse during provocative maneuvers about the shoulder with reproduction of ulnar nerve symptoms is suggestive of thoracic outlet compression. Ulnar neuropathy at the wrist caused by ulnar artery thrombosis (hypothenar hammer syndrome) can be suspected with a positive Allen test and confirmed with ultrasound or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA). The presented case is typical for a compressive neuropathy of the ulnar nerve at the wrist. Although most cases of carpal tunnel syndrome are idiopathic, many presentations of ulnar tunnel syndrome are associated with some underlying anatomical aberration. Ganglia, fractures of the hook of the hamate and distal radius, and anomalous muscles may all be causes of ulnar nerve compression at the wrist. Fractures or ganglia should be suspected in any patient with a history of trauma to the wrist. Anomalous muscles in the ulnar tunnel are rarely palpable on physical examination but can be seen on MRI (although this is not routinely necessary). Ulnar neuropathy at the wrist can also be seen in patients with inflammatory conditions (e.g., gout, rheumatoid arthritis) and occasionally in association with carpal tunnel syndrome. Certain occupations may predispose patients to ulnar tunnel syndrome, including vibration exposure, repetitive blunt trauma, and long-distance cycling. Cubital tunnel syndrome may present with similar findings; however, it is more commonly associated with activities causing prolonged elbow flexion or direct pressure on the ulnar nerve at the medial elbow. Patients often complain of symptoms that awaken them from sleep. Sensory changes in the dorsal ulnar aspect of the hand are more consistent with a proximal compression such as cubital tunnel syndrome. Similarly, ulnar nerve compression at the elbow may cause weakness or atrophy of more proximally innervated flexor digitorum profundi (FDP) and flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU). Other conditions that may mimic ulnar tunnel syndrome include cervical nerve root compression, thoracic outlet syndrome, and peripheral neuropathy (e.g., diabetes, chronic alcoholism). The most important tools for diagnosing ulnar tunnel syndrome are the clinical history and physical exam. Nerve conduction testing, electromyography, MRI, and ultrasound can be used to support the diagnosis and detect causes of the compression. Electrodiagnostic tests are often done early in the course of symptoms because they are easy to obtain. These tests are not necessary to make the diagnosis because they are often normal early in the disease process and a normal test does not rule out the diagnosis. Slowing of conduction (demyelination) is evident in testing only when all of the large myelinated fibers are affected. Increases in sensory and motor latencies indicate slowing of nerve conduction velocity. If the nerve becomes demyelinated and compression continues, the axons begin to die off and the amplitudes decrease. Electromyography can be performed for both the median and the ulnar nerve distributions above and below the wrist. These tests can also assist in differentiating ulnar tunnel syndrome from more proximal compressive neuropathies. They may also assist when symptoms are atypical due to crossover from the median nerve (Martin-Gruber anastomosis) or from a double crush syndrome. MRI or ultrasound can be useful if there is a space-occupying structure present, such as a ganglion, mass, or anomalous muscle. Ultrasound or MRA will demonstrate arterial thrombosis or pseudoaneurysm. Radiographs or, occasionally, computed tomographic (CT) scans of the wrist may be required to rule out associated injuries (e.g., hook of the hamate fractures). The initial management of mild and moderate ulnar tunnel syndrome without weakness should be conservative with wrist splinting and work or activity modifications. This should be continued until symptoms progress, weakness develops, or conservative measures fail after extended treatment. The decision to undergo surgical decompression should be reserved for patients that fail extended conservative treatment and those with severe symptoms, progression of symptoms, and presentation with axonal loss, and when masses or anomalous muscles are present. An evaluation should be done for proximal sources of compression and for concomitant carpal tunnel syndrome. This will increase the chances of a successful procedure leading to high patient satisfaction. Surgical management should consist of decompression of the ulnar nerve throughout the Guyon canal: incising the distal antebrachial fascia, volar carpal ligament, and proximal hypothenar fascia, following the nerve until it passes around the hook of the hamate. The senior author (DRS) prefers a curvilinear incision beginning proximal to the wrist crease over the FCU tendon and following the course of the ulnar nerve between the pisiform and hook of the hamate. Others have recommended a more extensile carpal tunnel incision. Care is taken to avoid injury to the palmar cutaneous branch of the ulnar nerve in the distal wound. The neurovascular bundle is identified proximally under the FCU by releasing the antebrachial fascia and followed distally, incising the volar carpal ligament. Decompression is continued distally around the hook of the hamate just below the leading edge of the hypothenar muscles and fascia. The hypothenar muscles are divided at this edge and elevated to allow the release of any tendinous bands (Fig. 28–3). Sensory and motor branches should be individually identified and the entire ulnar tunnel visualized to rule out all possible sites of mechanical compression. The ulnar artery should also be visualized and protected during the dissection. In patients with concomitant carpal tunnel syndrome, incising the floor of the Guyon canal (transverse carpal ligament) will decompress the median nerve. The wrist is placed in a soft, bulky dressing, and range of motion exercises are begun in the early postoperative period after suture removal. A nighttime wrist splint may be used for patient comfort during the first 2 to 3 weeks after decompression. Formal hand therapy may occasionally be required to facilitate recovery.

Case Presentation

Case Presentation

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Anatomy

Anatomy

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Diagnostic Tests

Diagnostic Tests

Management Options

Management Options

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree