CHAPTER 110 UREA CYCLE DISORDERS

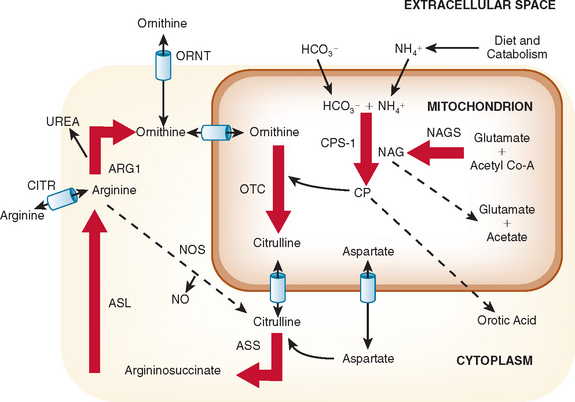

The urea cycle is a sequence of six enzymatic and two transport steps necessary to metabolize and excrete the nitrogen generated by the breakdown of amino acids in protein and other nitrogen-containing molecules (Fig. 110-1). The diet and the breakdown of endogenous tissues, particularly of skeletal muscle, are important sources of protein. Endogenous protein breakdown during episodes of acute catabolism presents the deficient ureagenic system with an overwhelming burden and results in the hyperammonemia that occurs in acute infections, after parturition, or during the menstrual cycle.1 The complete urea cycle is found only in the liver, although individual enzymes are present at lesser levels in other organs and may have additional metabolic roles. Severe liver disease with biosynthetic failure may also result in a deficient urea cycle and hyperammonemia. The first three enzymes in this cycle, N-acetylglutamate synthase (NAGS), carbamoyl phosphate synthase I (CPSI), and ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC) function inside mitochondria, and the latter three, argininosuccinic acid synthase, argininosuccinic acid lyase (ASL), and arginase, act in the cytosol. The two transporters are for ornithine and aspartate. Defects in citrin, the transporter for aspartate, causes citrin deficiency, also called citrullinemia type II. Defects in ornithine translocase, the transporter for ornithine, causes ornithine translocase deficiency (ORNT1), also called hyperammonemia, hyperornithinemia, and homocitrullinuria syndrome.

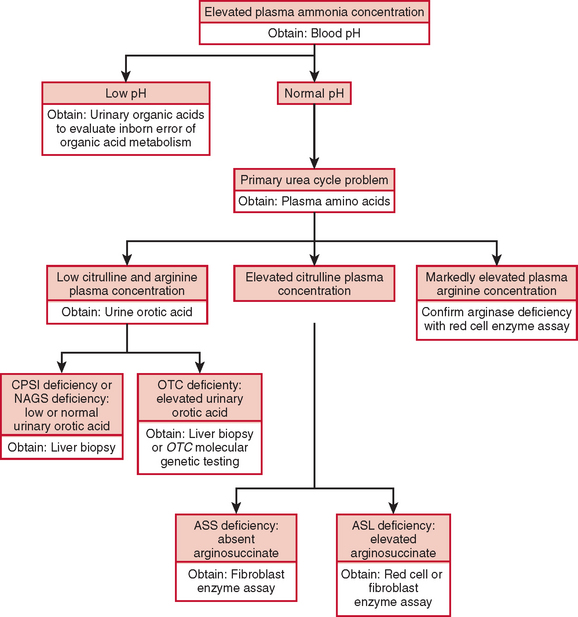

Defects in all six steps of the urea cycle and in the transporters are known. Any deficiency of these proteins may result in the accumulation of excess ammonia in the body. Ammonia is toxic to the central nervous system, and any continuous or intermittent elevation of ammonia can result in encephalopathy and neurological damage. This damage can lead to seizures, psychosis, mental retardation, and death. The essential genetic characteristics of the eight disorders are summarized in Table 110-1.

DEFINITION

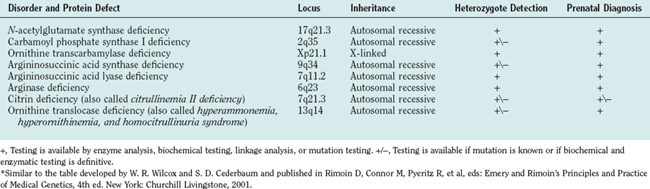

The diagnosis of a urea cycle disorder is based on clinical examination and on biochemical, enzymatic, and molecular analyses. A urea cycle defect is first suspected in an infant with anorexia, alterations in respiratory function and thermoregulation, lethargy, seizures, and deteriorating neurological status or in a child with decreased appetite, vomiting, lethargy, behavioral abnormalities, and an altered finding on neurological examination. In the affected older child or adult, blood ammonia determination should be part of the evaluation of any acute encephalopathy or recurrent late-onset psychosis or somnolence.2 The diagnosis is supported by an elevated plasma ammonia concentration with a normal anion gap and a normal serum glucose concentration (Fig. 110-2). An encephalopathic electroencephalographic pattern during an episode of hyperammonemia and evidence of brain atrophy on magnetic resonance imaging, although nonspecific, provide further support for the diagnosis of a urea cycle defect.

Plasma quantitative amino acid analysis can be used to aid in the delineation of the specific urea cycle disorder. Plasma amino acid analysis reveals reduced levels of arginine in all urea cycle disorders except arginase deficiency, in which arginine levels are elevated. Citrulline levels can also aid in discriminating the various urea cycle defects. Citrulline is produced by the first three enzymes, NAGS, CPSI, and OTC, and decreased levels are found when the level of any of these enzymes is deficient. In contrast, citrulline levels are increased with deficiencies of argininosuccinic acid synthase and ASL, because citrulline serves as a substrate for these more distal reactions. Urinary orotic acid levels are also used to differentiate CPSI and NAGS deficiency from OTC deficiencies. In the former, orotic acid levels are normal or reduced, whereas in the latter, they are elevated. A definitive diagnosis is made through measurement of enzyme activity, often from a liver tissue sample. If liver biopsy is not possible, diagnosis can be based on family history, clinical presentation, amino acid and orotic acid testing, and molecular genetic testing. These laboratory studies are carried out in highly specialized laboratories, which can be found on the GeneTests website (www.genetests.org).

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Seven of the eight urea cycle disorders—NAGS, CPSI, argininosuccinic acid synthase, ASL, arginase, ORNT1, and citrin deficiencies—are inherited as autosomal recessive traits. OTC deficiency is an X-linked disorder. Because of the absence of nationwide neonatal screening for these disorders, the true incidence of the individual urea cycle defects is not known. The estimated combined incidence for all urea cycle defects is 1 per 8200. OTC deficiency has the highest incidence, and arginase and NAGS deficiencies, the lowest.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Many newborns with a severe enzyme deficiency initially appear well but rapidly develop hyperammonemia and lethargy, anorexia, abnormal respiratory patterns, hypothermia, seizures, abnormal posturing, and deterioration into coma. This process is accompanied by cerebral edema. Severe deficiency of NAGS, CPSI, OTC, argininosuccinic acid synthase, or ASL, the first five enzymes in the cycle, almost invariably manifests within the first few days after birth and has a high mortality rate. Children with arginase, ORNT1 and citrin deficiencies can present in childhood, but episodes of symptomatic hyperammonemia are uncommon. In partial urea cycle enzyme deficiencies, individuals do well until an intercurrent illness or other stress results in a metabolic crisis with ammonia accumulation. In these individuals, the first recognized clinical episode may be delayed for months or years, and these patients typically have serial and milder elevations of plasma ammonia concentration throughout their lives. These individuals may have only recurrent abdominal pain, and the first indication of an inborn error may be developmental delay resulting from ammonia intoxication.

Neurotoxicity

A common manifestation of all urea cycle disorders is episodic encephalopathy associated with hyperammonemia. Although ammonia is a well-recognized neurotoxin, the nature and specific effect that hyperammonemia may have on the central nervous system is not well understood. During a crisis, hyperammonemia causes increased blood-brain barrier permeability, depletion of intermediates of energy metabolism, and disaggregation of microtubules. Ammonia is toxic to the central nervous system even when levels are only mildly elevated, as during long-term therapy. Mildly elevated ammonia levels may cause alterations of axonal development and alterations in brain amino acid and neurotransmitter levels.

Neuroimaging Abnormalities and Neuropathology

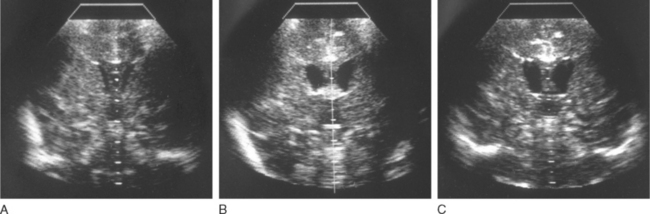

Head ultrasonography performed on neonates during initial presentations has revealed cerebral edema with largely obliterated ventricles. In surviving patients, the edema recedes with normalization of ammonia level, and the ventricles often become enlarged, as one manifestation of the cerebral atrophy that has occurred (Fig. 110-3). Hyperammonemic episodes at later ages are also accompanied by cerebral edema, which becomes even more dangerous once cranial sutures have fused. After hyperammonemic coma, magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography also demonstrate increased sulcal markings, bilateral symmetrical low-density white matter lesions, and diffuse atrophy, sparing the cerebellum. In patients who have died during a hyperammonemic crisis, neuropathological changes have included intracerebral hemorrhage, prominent cerebral edema, swelling of type II astrocytes, and generalized neuronal cell loss (Fig. 110-4). Neuropathology in older children has included ulegyria, cortical atrophy with ventriculomegaly, and prominent cortical neuronal loss.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree