DEPRESSION COMPLICATING VASCULAR DISEASE

Stroke and Mood Disorder

Stroke is associated with a high risk of depression as well as pathological laughing or crying and emotionalism. These are covered in Chapter 82.

Heart Disease

Soon after a coronary event about 15–20% of patients develop depressive symptoms1. By two months, out of 804 patients with stable coronary heart disease (CHD), 7.1% met criteria for major depression and 5.3% for generalized anxiety disorder2.These rates are at least double that expected in the general population.

Diabetes

The frequency of type 2 diabetes increases with age. In a cohort of patients aged 70–79 years followed for about six years those with diabetes had an increased rate of depression which attenuated after adjustment for diabetes-related co-morbidities, although this still represented a significantly increased risk compared to controls3.In this study HbA1c was a predictor of recurrent depression.

Blood Pressure and Depression

Whether the prevalence of depression increases as blood pressure rises is controversial. Rabkin etal.4 found a three-fold higher frequency of major depression in 452 patients treated for hypertension whereas Jones-Webb etal.5 found no association between resting blood pressure and self-rated depression in 4352 young subjects. Scalco etal.6 suggest that a link between depression and hypertension may be mediated by hyperreactivity of the sympathetic nervous system. There is also a potential link between low blood pressure and depression. An inverse relationship between low diastolic blood pressure (below 75 mmHg) and depressive symptoms (such as fatigue, pessimism and sadness) was shown in a study of 846 elderly men without a psychiatric diagnosis7.

Vascular Depression

Central to the notion of vascular depression is that vascular brain disease may predispose to depression, precipitate it or perpetuate it8. Features include reduced depressive ideation, more psychomotor retardation, poor insight, executive dysfunction (see below), greater disability and often an age of onset over 60. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has shown higher rates of hyperintensities in the deep white matter and basal ganglia compared with control subjects, an effect seen most in late-onset cases9. Epidemiological studies confirm that the severity and location (especially in the basal ganglia) of white matter lesions (WMLs) seem to be causally related to late-life depression10,11. Pathological data show that WMLs in the brains of depressed patients are more likely to be ischaemic compared to those seen in the brains of non-depressed subjects1.

A clear-cut association between the symptoms of vascular depression and common cerebrovascular risk factors (such as hypertension, smoking, hyperlipidaemia and diabetes) has not been shown and the vascular depression hypothesis has its critics. McDougall and Brayne12 analysed 13 studies comparing depressive symptoms in subjects with and without co-morbid vascular conditions and concluded there was insufficient evidence to agree an operational definition of vascular depression. However, Sneed etal.13 applied the statistical technique of latent class analysis to two naturalistic clinical trials of treatment in late-life depression. WML burden was the most accurate indicator of vascular vs. non-vascular depression. This internal consistency is important for confirming vascular depression as a distinct entity.

Chronic hypoperfusion (rather than small vessel infarction) may be another cause of vascular depression. Hypoperfusion might be secondary to hypotension (as discussed above), damage to blood pressure regulating mechanisms or arterial stiffness and/or failed compensation by the brain14. Brain hypoperfusion is not readily detectable by ‘bedside’ measures of cerebrovascular function other than perhaps by assessing postural hypotension.

The ‘Depression–executive dysfunction syndrome’ is an important feature of vascular depression15. Deficits involve executive tasks (planning, initiation and task persistence) and speed of information processing16. Clinically, these patients present with slow inefficient thinking, patchy memory impairment and are often apathetic.

DEPRESSION AS A RISK FACTOR FOR VASCULAR DISEASE

A number of studies have demonstrated that depression is a risk factor for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events. However, the quality of evidence has been variable, for example fully accounting for factors which might explain such an association (such as severity of cardiac disease and vascular risk factors) markedly attenuates the association.

Stroke

Whether depression is a risk factor for stroke is controversial. In the Framingham study17 participants aged 65 or below with raised depression scores on a rating scale were four times more likely to experience a stroke or transient ischemic attack compared with those of the same age without depression, after controlling for smoking status and education. The effect was not seen among those who were 65 or older. A positive association between the presence of depression and the risk of stroke across the entire adult age range was, however, found in another study18.

Wouts etal.19 reported that patients with baseline cardiac disease and depression were most at risk of later stroke and that there was a dose–response relationship: greater severity and chronicity of depression increased the risk. This may reflect the synergistic effect of depression and vascular disease or it may be that depressive symptomatology merely reflects the severity of underlying vascular disease (reverse causality).

Heart Disease

A meta-analysis concluded that depressed mood moderately increases the risk of myocardial infarction, coronary heart disease and cerebrovascular diseases by about the same amount (odds ratio between 1.43 and 1.63)20 and adversely affects the prognosis of CHD to about the same degree21. The evidence for depression as an inde-pendentrisk factor for vascular events has been sufficiently robust for the American Heart Association to recommend screening for depression in cardiac patients22. As a risk factor for cardiovascular disease, depression may rank somewhere between active and passive smoking23. However; adjustment for baseline factors, especially left ventricular function, substantially attenuates this association.

A Dutch epidemiological study of older adults showed that cardiac patients with minor (subthreshold) depression had a relative risk of subsequent cardiac mortality of 1.6 rising to 3.0 for those with major depression, after adjustment for confounding factors24, an effect replicated by Ariyo and colleagues25. Negative effects on cardiac outcome are seen whether or not subjects are healthy at baseline and can last for many years26 but generally manifest themselves within the first year after an acute myocardial infarct22.

Diabetes

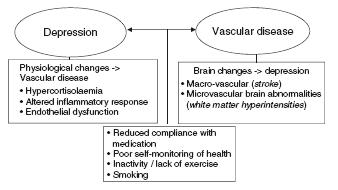

For diabetes, again there is some evidence that depression is a risk factor for diabetes but this may apply mainly to the non-insulin dependant type27, the commonest form in older adults. The risk though is only modest once other factors (for example lifestyle) are accounted for. The occurrence of diabetic complications and poorer glycaemic control are more likely in depressed subjects because depression undermines motivation (Figure 75.1). Painful neuropathy may be another factor in triggering depression. Diabetes can cause small vessel pathology in the brain that leads to subcortical encephalopathy, not unlike that seen in vascular depression. This may lead to both cognitive impairment and depressed mood.

Hypertension

Some evidence suggests that depressed people have higher resting blood pressure than non-depressed people6. This may be because depression reduces medication conpliance, but one study of normotensive, non-elderly subjects followed over several years showed that high levels of depressive symptoms doubled the risk of hypertension28.

Cholesterol

Low cholesterol may reduce serotonin available to the brain, although there is no convincing evidence which links cholesterol and depression via vascular disease. One study of statins did not demonstrate that lowering cholesterol increased depression29.

POSSIBLE MECHANISMS OF CAUSATION

The relationship between depression and vascular disease is two-way (Figure 75.1) and there are aetiological factors which may be shared, such as genetic risk and lifestyle factors.

Genetic Mechanisms

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree