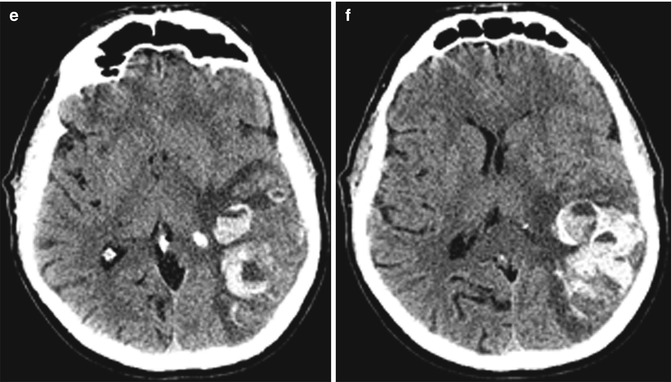

Fig. 32.1

Warfarin-associated intracranial hemorrhage. The patient underwent anticoagulation for a left MCA cardioembolic stroke shortly after atrial fibrillation ablation procedure. Axial non-contrast CT (a), axial DWI (b), and axial GRE (c) images demonstrate a left MCA territory infarct with cortical petechial microhemorrhage (arrowheads), but no gross hemorrhagic conversion apparent on CT. Axial non-contrast CT (d) obtained one later shows a small area of hemorrhagic conversion (arrow). Anticoagulation with Coumadin was reinstituted secondary to concerns of atrial fibrillation and the concern of new cardioembolic phenomena. The patient presented acutely 2 weeks later with an INR of 2.2 when axial non-contrast CT (e, f) demonstrated extensive hemorrhagic conversion with multiple hemorrhagic fluid levels

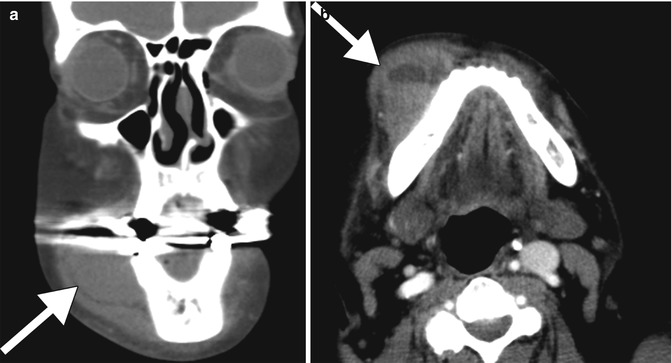

Fig. 32.2

Warfarin-associated facial hemorrhage. Coronal (a) and axial (b) CT images of the face show a large hematoma overlying the right mandible (arrows). Note the layering blood-fluid level on the axial image. The presence of a blood-fluid level has been found to be moderately sensitive but highly specific for the identification of a coagulopathic hemorrhage

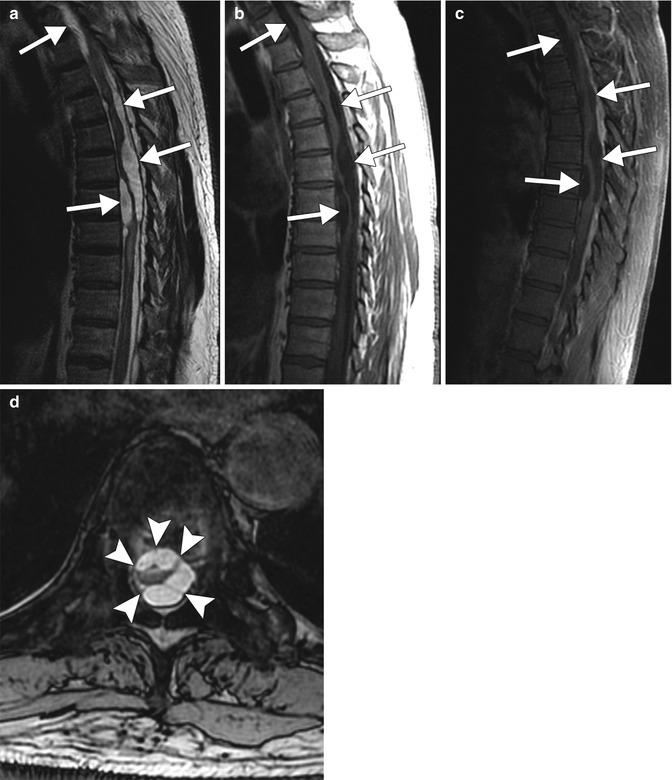

Hemorrhage associated with warfarin can occur in any CNS compartment, including epidural, subdural, and subarachnoid locations. In addition to the complications at the site of hemorrhage, more remote complications related may later ensue. For instance, a rare complication of intracranial subarachnoid hemorrhage is the development of adhesive arachnoiditis with arachnoid adhesions, septations, and cysts that mainly involve the cervical and thoracic spine (Fig. 32.3).

Fig. 32.3

Adhesive arachnoiditis as a late complication of Warfarin-associated subarachnoid hemorrhage. The patient has a history of prior intracranial and thoracic spine subarachnoid and subdural hemorrhage, presenting with several months of low back pain and progressive lower extremity weakness and paresthesias. Sagittal T2-weighted (a), sagittal T1-weighted (b), and sagittal T1-weighted post-contrast (c) images of the thoracic spine demonstrate distortion of the thoracic spinal cord in multiple areas associated extramedullary cystic spaces (arrows). Axial GRE (d) image depicts the morphologically abnormal spinal cord secondary to arachnoid adhesions (arrowheads)

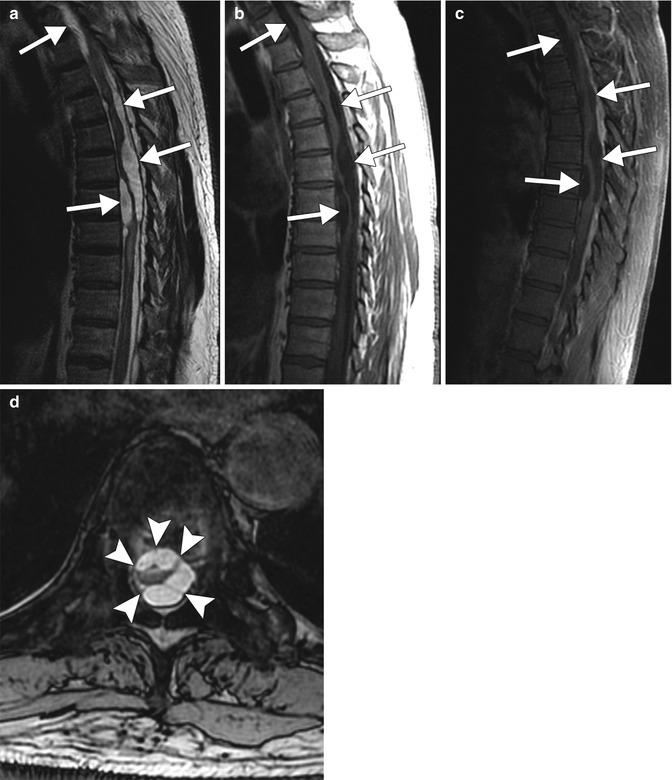

Other less common side effects include warfarin necrosis and fetal warfarin syndrome (Binder phenotype). Warfarin necrosis occurs early with the initiation of warfarin therapy and is believed to occur secondary to decreased levels of protein C, which is an anticoagulant. This response is exaggerated in patients who express genetic mutations resulting in low protein C levels. When anticoagulation is initiated, vicarious administration of heparin products is used to offset these processes. Warfarin is a teratogen during the first trimester of pregnancy. Several findings are associated with fetal warfarin syndrome, including epiphyseal stippling, nasal hypoplasia (Fig. 32.4), nasal cartilage calcification, scoliosis, and brachydactyly. Warfarin use later in pregnancy is considered impart a lower risk of birth defects.

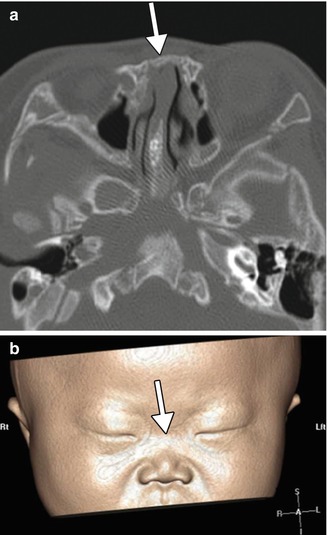

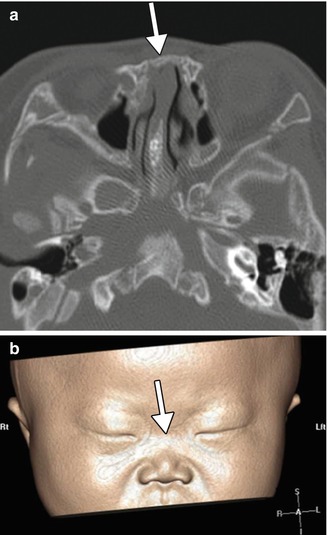

Fig. 32.4

Fetal warfarin syndrome. Axial (a) and non-contrast bone window CT images of the brain and a 3D surface-rendered image of the face (b) in an infant demonstrating dramatic midface and nasal hypoplasia (arrows) in the setting of warfarin use in the first trimester (Courtesy of Carolyn Robson)

32.4 Differential Diagnosis

The differential considerations for warfarin-induced complications encountered on imaging are numerous, and clinical history is critical for establishing the appropriate diagnosis. However, it should be cautioned that patients on Coumadin may nevertheless have a separate etiology of the abnormality encountered on imaging.

Other causes of intracranial hemorrhage: There are several causes of intracranial hemorrhage other than those secondary to anticoagulation. Some of these include hypertension, AVM, hemorrhagic neoplasm, and amyloid angiopathy. Clinical history is important in helping to narrow the differential diagnosis. Other imaging modalities including MRI/MRA as well as CTA can also be helpful to further elucidate the underlying cause of intracranial hemorrhage.

Hemorrhagic neoplasm: Intracranial hemorrhage can also be secondary to intracranial neoplasm. Some of these include primary brain neoplasms, the most common being glioblastoma multiforme as well as hemorrhagic metastases. Imaging characteristics will vary depending on the type of neoplasm. The hallmark of a hemorrhagic neoplasm is nodular enhancement (Fig. 32.4), a finding that can obscured in the acute setting due to the mass effect exerted by the acute hemorrhage and edema. In such cases, it is important to obtain follow-up imaging.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree