Chapter 24 Wilson disease

Wilson disease

Wilson disease is an inborn error of copper metabolism manifest as hepatic cirrhosis and basal ganglia damage (Wilson, 1912). Wilson disease is one of the few curable movement disorders at the present time. It presents in so many guises that any patient with a movement disorder under the age of 50 years should be considered to possibly have Wilson disease. It is sufficiently rare that the diagnosis is often missed. In a review of 307 patients, the average delay to diagnosis was 2 years and misdiagnoses included schizophrenia, juvenile polyarthritis, rheumatic chorea, nephrotic syndrome, metachromatic leukodystrophy, congenital myopathies, subacute sclerosing panencephalitis, and neurodegenerative disease (Prashanth et al., 2004).

Wilson disease is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait. The gene responsible lies on chromosome 13q14.3 (whereas that for ceruloplasmin is located on chromosome 8 (Wang et al., 1988). The Wilson disease gene encodes for a copper-transporting P-type ATPase (ATP7B) (Petrukhin et al., 1993; Tanzi et al., 1993). Over 300 mutations of the gene have been detected, and more are being found regularly (Thomas et al., 1995; Shah et al., 1997; Curtis et al., 1999; Lin et al., 2010). The enzyme binds copper in its large N-terminal domain and aids in intracellular processing in the hepatocyte (Ala et al., 2007).

Intestinal absorption of copper is normal in Wilson disease (normal adults absorb about 1 mg of copper daily), as is subsequent transport into the hepatocyte. Since absorption is about 1 mg per day, and the requirement is for 0.75 mg per day, about 0.25 mg must be excreted from the body each day (Lorincz, 2010). There are two pathways for copper excretion from the hepatocyte aided by ATP7B. One is the attachment to ceruloplasmin in the Golgi apparatus, and subsequent delivery of the copper–ceruloplasmin complex into the serum. A second is promotion of copper excretion into the bile. The mutations lead to failure to excrete copper by both routes, causing build-up of copper in the hepatocyte and eventual spillover of free copper into the circulation. This leads to a substantial positive net copper balance and systemic copper poisoning (Cuthbert, 1998; Loudianos and Gitlin, 2000). There is increased circulating free copper and excessive urinary excretion of copper, but this is insufficient to prevent copper accumulation (the normal human body contains 80 mg of copper). Excess copper in the liver causes progressive liver damage. Copper also accumulates in brain and other sites (the eye, kidney, bones, and blood tissues being particularly vulnerable to copper toxicity). Some of the toxicity of copper may be due to oxidative mechanisms.

Curiously, monozygotic twins might be discordant for Wilson disease, suggesting that epigenetic or environmental factors must also be important (Czlonkowska et al., 2009).

The prevalence of heterozygous carriers, who have inherited only one abnormal gene, is around 1 in 100–200 of the population (Reilly et al., 1993). Heterozygotes do not develop Wilson disease, but may exhibit mild abnormalities of copper metabolism, and prevalence is estimated to be about 17 per million of the population.

The initial manifestations of the illness (Table 24.1) are neurologic in about 40% of patients (usually after the age of 12 years) (Brewer, 2000a; Lorincz, 2010). The remainder present with symptoms of liver disease (about 40%) (usually at an earlier age) (Manolaki et al., 2009) or a psychiatric illness (about 15%). The psychiatric picture may show a change in personality or mood. Psychosis is rare. What determines these individual variations in clinical presentation is not clear. One factor has been determined; patients with ApoE epsilon3/3 genotype have delayed onset of symptoms compared to all other ApoE genotypes (Schiefermeier et al., 2000). Symptoms usually appear between the ages of 11 and 25 years, but can occur as early as 4 and as late as 50+ years (Starosta-Rubinstein et al., 1987; Stremmel et al., 1991; Walshe and Yealland, 1992; Ferenci et al., 2007). Some patients with Wilson disease have autonomic nervous system abnormalities (Bhattacharya et al., 2002; Meenakshi-Sundaram et al., 2002).

Table 24.1 Presentation of Wilson disease

| Liver disease (40%) |

| Neurologic (40%) |

| Psychiatric (15%) |

| Others (5%) |

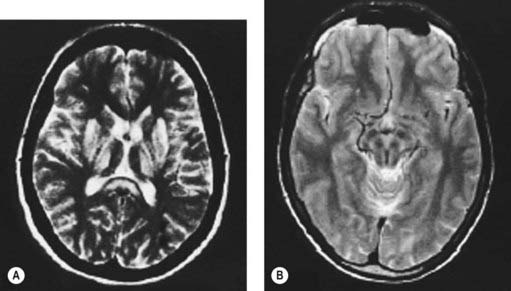

The pathologic abnormalities in the brain are primarily in the basal ganglia, with cavitary necrosis of the putamen and caudate, associated with neuronal loss, axonal degeneration and astrocytosis (Fig. 24.1). In addition, there is cortical atrophy. In a recent pathologic study of eight patients, six had neurological manifestations clinically (Meenakshi-Sundaram et al., 2008). Of these six, five had central pontine myelinolysis, five had subcortical white matter cavitations, four had putaminal softening, and six had variable ventricular dilatation. The liver in Wilson disease develops cirrhosis, typically of the nodular type.

Figure 24.1 Postmortem brain of a patient with Wilson disease showing the cavitary necrosis of the basal ganglia.

From Wilson SAK. Progressive lenticular degeneration: A familial nervous disease associated with cirrhosis of the liver. Brain 1912;34:295–507.

A detailed analysis of the psychiatric presentation of 15 patients showed an affective disorder spectrum abnormality in 11 and a schizophreniform illness in 3 (Srinivas et al., 2008). Note was made that while the psychiatric symptoms improved in five patients with de-coppering therapy, seven patients needed symptomatic treatment as well.

Those with neurologic abnormalities usually present in the second or third decade, as (1) an akinetic-rigid syndrome resembling parkinsonism, (2) a generalized dystonic syndrome (pure chorea is uncommon), or (3) postural and intention tremor with ataxia, titubation and dysarthria (pseudosclerosis) (Table 24.2 and Video 24.1). The tremor may be mild, but is classically a slow, high-amplitude proximal tremor with the appearance of “wing-beating” when the arms are elevated and the hands placed near the nose. Dysarthria and clumsiness of the hands are common presenting features. The speech abnormality may include rapid speech, hypophonia, and slurring. It is most unusual for the illness to present with a gait disorder. No two patients with Wilson disease are ever quite the same. The facile grinning face with drooling saliva is characteristic. Early pseudobulbar features are common. Eye movements can be disordered with slow saccades (Kirkham and Kamin, 1974) and occasionally ophthalmoplegia (Gadoth and Liel, 1980). Vision and sensation are not affected, and paralysis does not occur although pyramidal signs may be evident. Sphincter control is spared. Seizures are infrequent (Smith and Mattson, 1967). Cognitive changes are common, even to the extent of a frank dementia. Changes in school or work performance are often the initial indication of the illness. Impulsiveness or antisocial behavior, and other indices of personality change are common (Dening and Berrios, 1989; Dening, 1991; Akil and Brewer, 1995). ![]()

Table 24.2 Number (percentage) of Wilson disease patients with different initial symptoms and signs

| Juveniles (n = 65) | Adults (n = 71) | |

|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | ||

| Personality change | 21 (32) | 23 (32) |

| Speech defect | 63 (41) | 42 (30) |

| Drooling | 31 (20) | 22 (16) |

| Dysphagia | 14 (9) | 7 (5) |

| Hand tremor | 48 (31) | 55 (39) |

| Hand clumsy | 32 (21) | 20 (14) |

| Abnormal gait | 34 (22) | 18 (13) |

| Fall at work or school | 40 (26) | |

| Signs | ||

| Personality disorder | 14 (21) | 13 (18) |

| Dysarthria | 34 (52) | 19 (27) |

| Gait abnormal | 8 (12) | 5 (7) |

| Eye movement abnormal | 4 (6) | 4 (6) |

| Drooling | 18 (28) | 11 (15) |

| Parkinsonian facies | 15 (23) | 5 (7) |

| Open mouth | 10 (15) | 0 (0) |

| Bradykinesia | 6 (9) | 3 (4) |

| Tongue abnormal | 11 (17) | 9 (13) |

| UL tremor | 17 (26) | 23 (32) |

| UL dystonia | 14 (21) | 13 (18) |

| UL spontaneous movements | 8 (12) | 0 (0) |

| LL tremor | 2 (3) | 6 (8) |

| LL dystonia | 12 (18) | 0 (0) |

| LL spontaneous movements | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Liver disease | 19 (29) | 8 (11) |

UL, upper limb; LL lower limb.

From Walshe JM, Yealland M. Wilson’s disease: the problem of delayed diagnosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1992;55(8):692–696.

Many of those with neurologic complaints give a history of prior or concurrent liver disease. This may consist of a previous episode of acute hepatitis, chronic active hepatitis, portal hypertension, or asymptomatic hepatosplenomegaly (Scheinberg and Sternlieb, 1984). An unexplained hemolytic anemia, renal disease with hematuria, amino-aciduria, renal tubular defects, and calculi (Wiebers et al., 1979), or skeletal disease with osteoporosis/osteomalacia (Carpenter et al., 1983) are other clues.

Laboratory testing can make a definitive diagnosis (Mak and Lam, 2008). The diagnosis (Table 24.3) is first tested by looking for reduced serum ceruloplasmin. However, 5% of those with Wilson disease have a normal serum ceruloplasmin. The concentration of this copper protein may be low in heterozygotes, in patients with severe protein loss, and with severe liver disease of other cause. Serum ceruloplasmin may be increased by pregnancy and estrogens. Serum total copper is low in many patients (but nonspecific; Kumar et al., 2007), and urinary copper excretion is nearly always raised. However, anything causing cholestasis (particularly drugs) may raise serum copper and increase urinary copper excretion. When an expert examines the cornea with a slit lamp, virtually all patients with neurologic Wilson disease show Kayser–Fleischer rings in the Descemet membrane (Fig. 24.2) (Wiebers et al., 1977). However, rare patients with neurologic Wilson disease but no Kayser–Fleischer rings have been described (Ross et al., 1985; Demirkiran et al., 1996). A Kayser–Fleischer ring occasionally is only seen in one eye (Madden et al., 1985). The yellow and brown copper deposits are seen at the limbus of the cornea, usually first visible and most dense at the upper and lower poles of the eye. Kayser–Fleischer rings are not present in all patients with the liver manifestations of Wilson disease and other liver disease can produce them (Fleming et al., 1977).

Table 24.3 The diagnosis of Wilson disease (WD)

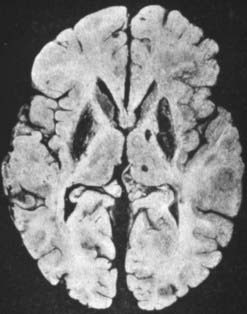

Computed tomography (Harik and Post, 1981; Williams and Walshe, 1981) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Starosta-Rubinstein et al., 1987; Alanen et al., 1999; Giagheddu et al., 2001) of the brain usually reveals changes in the basal ganglia, which are reversible with treatment. Caudate and putamen show increased T2 signal, and there may be similar changes in the substantia nigra pars compacta, periaqueductal gray, the pontine tegmentum, and the thalamus (Fig. 24.3A) (Saatci et al., 1997). Particularly striking are the putaminal lesions with a pattern of symmetric, bilateral, concentric-laminar T2 hyperintensity. Hyperintensity of the mesencephalon with sparing of the red nuclei and lateral aspect of the substantia nigra gives rise to the “face of the giant panda sign” (Fig. 24.3B) (Giagheddu et al., 2001). A “double panda sign” has also been described (Jacobs et al., 2003; Liebeskind et al., 2003). There can be hyperintensity of the middle cerebellar peduncle (Uchino et al., 2004). Another change has a similar appearance to central pontine myelinolysis, and this will improve with therapy (Sinha et al., 2007b). Diffusion-weighted MRI might also be useful (Favrole et al., 2006). In a study of 100 patients with various extrapyramidal diseases, the MRI features most useful to diagnose Wilson disease were the “face of giant panda” sign (seen in 14.3%), tectal plate hyperintensity (seen in 75%), central pontine myelinolysis-like abnormalities (seen in 62.5%), and concurrent signal changes in basal ganglia, thalamus, and brainstem (seen in 55.3%) (Prashanth et al., 2010).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree