21 CHAPTER CONTENTS UNEMPLOYMENT, EMPLOYMENT BARRIERS AND MENTAL ILL-HEALTH BARRIERS TO VOCATIONAL OPTIONS AND EMPLOYMENT ACCESS, OPPORTUNITIES AND SUPPORTS TO FIND AND SUSTAIN EMPLOYMENT Creating New Employment Options BRINGING A VOCATIONAL FOCUS TO MENTAL HEALTH PRACTICE PRACTICE AS A VOCATIONAL SPECIALIST Creating Relationships with Individuals Creating Relationships with Other Mental Health Workers and Supporters Creating Relationships with Other Agencies/Services Creating Relationships with Employers and Workplaces Work is a defining feature of everyday life in human communities and a major occupational role of adulthood; indeed, many aspects of sustaining life and meeting human needs depend upon the income and relationships sustained through work (Grove et al. 2005). Consequently, work powerfully shapes people’s lives socially and economically, as well as affirming a sense of productivity and valued identity within society. ‘What do you do?’ Having an answer to that question gives us immediate entrée to the normal flow of life …. Work gives us the opportunity to develop relationships in which we can feel good about ourselves. When our relationships develop out of shared respect for the unique talents we all have, it is much harder to sink and destroy them with feelings of not being worthwhile enough …. We know deeply that we are being taken seriously and respectfully by someone who is depending on us to complete a job. (Vorspan 1992, p 52) That access to decent and productive work, with fair pay in conditions of freedom, equity, security and human dignity is also considered the right of all men and women (International Labour Organization 2004) and underscores the importance of work. Not surprisingly then, illness-related disruptions to people’s working lives, prolonged unemployment or exclusion from work are profoundly felt by affected individuals, their families and communities. People with mental ill-health are among the most excluded from the workforce, experiencing very high unemployment rates and many barriers to participation in paid work. This is despite people consistently reporting their wish and preference to work; the central importance of meaningful occupation in supporting recovery and promoting social inclusion; and the existence of effective ways to support people to access employment and pursue vocational goals. Thus, this chapter addresses: ■ What is meant by work and productivity ■ The restrictions and barriers to participation in education and employment and the importance of addressing these issues in relation to recovery and social inclusion ■ Approaches to supporting people to pursue their vocational goals and gain access to jobs and careers that enable social and economic participation and inclusion ■ How occupational therapists can bring a vocational focus to mental health practice. The term occupation is often understood as one’s work, vocation or employment. Work is a sufficiently commonplace idea that its meaning may be assumed, even taken-for-granted, yet defining the concept of work is not straightforward (O’Halloran and Innes 2004; Jarman 2010). Paid occupations may be the most readily recognized and categorized as work. Indeed, the terms work, jobs and employment are frequently used interchangeably. In comparison, child-rearing, caring and domestic activity might be experienced as work, but are not necessarily remunerated. In considering what is meant by work and productive occupations, Ross (2007) suggested distinctions between paid work, unpaid, hidden and substitute work may be useful: ■ Unpaid work – work that sustains and enriches society but does not attract individual remuneration. Often undervalued, its economic contribution in society is substantial if the financial cost of the paid work necessary to replace the unpaid contributions of domestic work, caring and volunteering in communities is considered. Much unpaid housework and caring work is not highly visible, being typically carried out by women within the domestic sphere. Volunteering usually occurs outside the home, where particular interests or concerns may be pursued, social connections made and vocationally relevant skills developed or used. Some people choose to participate in volunteering as a meaningful occupation in its own right, while for others it offers opportunities for personal development, skills and experiences relevant to gaining employment. Education and learning too are unpaid but, like paid work, typically impose structure on one’s time and, like volunteering, provide avenues for personal and vocational development. ■ Hidden work – some types of work may include goods and services provided in exchange for cash or other services, but are not formally counted as income. Hidden work may involve illegal activities, such as trading illicit drugs, or exploitation through forced labour for little or no money without safe and decent working conditions. ■ Substitute work – a segregated form of work, also referred to as sheltered work, traditionally organized to provide daily structure and work-like activity for disabled people as a substitute for employment, but without access to the same rights and working conditions as the mainstream workforce. Once deemed pre-vocational training, this type of work often created segregated substitutes for, rather than pathways into, jobs that afford the social and economic benefits of community life (Warner 2004; Schneider 2005). Many now consider substitute work to be discriminatory and exclusionary (Ross 2007). As illustrated above, work is not readily distinguished from other forms of human activity and effort merely based on whether or not it is remunerated. Nor is work easily defined in contrast to leisure: for instance, people may pursue occupations like cooking, gardening, painting and so forth, as paid work or for leisure. Leisure is also often thought of as more freely chosen, discretionary and pleasurable than work, yet leisure may lose these meanings when people are out of work, so that work and leisure appear to derive meaning from each other (O’Halloran and Innes 2004; Ross 2007). Therefore, how the concept of work is understood is shaped by the meanings and values attached to different occupations by individuals, communities and cultures over time (O’Halloran and Innes 2004; Ross 2007; Jarman 2010). Sociological, psychological, economic and occupational perspectives of the nature and purpose of work overlap somewhat but they also differ (Ross 2007; Jarman 2010). These literatures are extensive; the following offer examples of their differing emphases. First, the division of labour that characterizes industrial societies offers one way to understand the role of occupations in society from a sociological perspective. Originating from French sociologist, Emile Durkheim, the sociological perspective has drawn attention to: the relative value and status in society of different types of work; the differing class, race and gender compositions of occupations; and how these relate to broad patterns of social inequality and disadvantage (Jarman 2010). Second, studies of unemployment and employment from a social psychological perspective have identified positive latent benefits of employment for health: that it imposes time structure and a demand for activity; involves regular shared experiences; links individual goals to collective purposes; facilitates access to social networks; and is important in defining identity (Jahoda 1981). Third, from an occupational perspective, work is typically viewed as an adult occupation encompassing a range of productive roles. For instance, productivity as described by the Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists (2002) refers to ‘occupations that make an economic and social contribution or that provide for economic sustenance’ (p. 37), so that this view of work is inclusive of paid employment, study, volunteering and unpaid domestic, parenting and caring work, as ways of being productive and contributing. The occupational perspective also seeks to understand these occupations in terms of their temporal, meaning, contextual and performance dimensions (Christiansen and Townsend 2010). Put another way, an occupational perspective leads us to ask questions about people’s occupations such as: how are they integrated into regular patterns and routines of time use? Why are they chosen, and what meanings do they hold? Where are they done? How are they done? How does context influence what is done? Furthermore, an occupational perspective differs from the aforementioned perspectives in its focus on the dynamic relationships and extent of fit between persons, their occupations, and the environments in which they are enacted (Christiansen and Townsend 2010). For occupational therapists, this notion of fit may be considered in relation to jobs and careers when working with people whose vocational options or working lives have been disrupted. For instance, when considering a person’s job, our focus will be the fit between the person, the demands of the job and the specific workplace environment. In turn, this focus may lead to identifying work adjustments to improve this fit. In comparison, to consider a person’s employment in terms of a career means focusing on the person’s vocational interests, preferences, skills and experiences and the match between these and possible employment options, a process referred to as job matching or career planning (O’Halloran and Innes 2004). Of interest too, from an occupational perspective, is the balance among the full range of work-related and other occupations in which people engage in daily life and the implications for their health, wellbeing, and participation in society (Backman 2010; Eklund et al. 2010). So, occupational therapists are concerned with the impacts of individuals’ occupations on their health, and the ways in which recovery and wellbeing may be supported through participation in personally and socially valued occupations. There are many economic, social and health-related reasons for being concerned about employment and mental health. In high-income countries internationally, mental ill-health is a leading cause of sickness absence. Unemployment among people with mental ill-health is very high: reported figures from English-speaking and European countries range between 60% and 90%; extensive across all relevant diagnostic categories; and higher for people with mental ill-health than other people in society (Lloyd and Waghorn 2010; Waghorn and Lloyd 2010). Mental ill-health also accounts for a substantial proportion of disability payments at a population level (Cai et al. 2007; Harvey et al. 2009). This means significant economic costs are associated with not adequately supporting people to retain and return to their jobs following sickness absence due to mental ill-health, and not addressing the vocational issues of unemployed people with ongoing mental ill-health. Paid employment is considered beneficial for health and wellbeing when it provides opportunities for control, using skills, pursuing goals, variety, physical security, money, social contact and a valued social position (Ross 2007), although insecure jobs and poor-quality working conditions may also undermine mental health (Butterworth et al. 2011). In comparison, unemployment has many reported adverse effects for those who personally experience job loss and lack of work: loss of income, purpose, structure, identity and social status, as well as poorer health (Ross 2007). For people with enduring mental ill-health, the stresses of working were traditionally thought to outweigh the disadvantages of being unemployed, yet the constant strains imposed by prolonged unemployment, poverty, isolation, and losses of self-respect, identity, purpose and routine are actually likely to worsen their circumstances (Marrone and Golowka 1999; Warner 2004). Their low levels of workforce participation should also not be taken to mean that people with mental ill-health are incapable of or do not want to work. To the contrary, the majority of people experiencing mental health issues report wanting access to work opportunities or to pursue vocational aspirations and, with the right supports, can and do engage in education, employment and other productive occupations (Fossey and Harvey 2010). Internationally recognition of these issues, along with the profound employment and social inequalities faced by people with mental health issues, has increased acknowledgement that their employment issues and social exclusion are inextricably linked (Grove et al. 2005). Paid employment or other ways to be productive and contribute in one’s communities, along with a decent standard of living and inclusive relationships, are considered key elements of social inclusion (Bates 2002; Repper and Perkins 2003). Similarly, people often report working and opportunities for meaningful occupation are central to the process of recovering (Davidson 2003; Krupa 2004; van Niekerk 2009). Qualitative studies of employment-related experiences from the viewpoints of people with direct experience report that gaining employment creates a sense of wellness, improved relationships, more positive self-appraisals, and greater optimism (Fossey and Harvey 2010). Other wide-ranging benefits of being employed identified in these qualitative studies include remuneration, more structured time use, greater autonomy, status and acceptance within society, a sense of purpose, feeling productive and useful to others, affirmation of ability and opportunities for social contact and personal development. Many of these are the same benefits reported by other employed people (Fossey and Harvey 2010). So, while their desire for work should hardly be surprising, people with mental ill-health face an extensive range of challenging barriers to finding and maintaining meaningful employment due to systemic, employer and job-related factors, in addition to personal factors. The availability of jobs in the labour market influences the likelihood of being employed, but those generally most at risk of losing jobs, job instability and unemployment include: the young and inexperienced, those with least vocation-related skills and qualifications, older workers, those in poor health and disabled people in society (Ross 2007). Hence, people experiencing mental health issues may be particularly vulnerable to difficulties obtaining jobs, losing jobs and to prolonged unemployment on health grounds. Their completion of formal education or vocational qualifications and gaining of work experience have also often been disrupted. Contributing factors are: the common onset of mental health issues in adolescence or early adulthood; the fluctuating nature of many mental health conditions; and attempts to return to study or work that fail due to inadequate support. These factors make jobs difficult to obtain and sustain, restrict career paths and earning potential, and can result in long-term exclusion from the mainstream workforce (Megivern et al. 2003; Lloyd and Waghorn 2010). Other wide-ranging barriers to participation in education and employment have been reported by people with direct experience: (Megivern et al. 2003; Blitz and Mechanic 2006; Thornicroft 2006; Forbess et al. 2010; Lloyd and Tse 2010; Waghorn and Spowart 2010), including: ■ inflexibility in working practices and educational course structures that respectively limit paid work and study choices particularly for those with fluctuating or episodic conditions ■ limited knowledge among employers about how to accommodate people with mental ill-health in the workplace, resulting in a reluctance to hire ■ low expectations or limited knowledge of mental health staff about opportunities to study/work, meaning that they either do not attend to vocational issues or convey pessimism about study/work prospects ■ views, held by mental health staff and/or carers, that work or study is too stressful/harmful, especially when it is identified as a trigger factor for a person’s ill-health, meaning that they discourage return to study or work ■ inadequate supports both within and outside the workplace or educational setting ■ ongoing dilemmas related to management of personal information and illness disclosure, including its potential for adverse consequences in job-seeking, on return to study or work following sick leave, and whilst engaged in education or employment ■ limited income and resources to enable job-seeking or study, such as transport, clothing and equipment ■ subjective concerns regarding the impact of medication effects or illness-related factors on managing study/work demands or performing well enough, and fears of becoming unwell and its consequences for study or employment and income ■ employment disincentives, such as risks to, or loss of, welfare entitlements and difficulties regaining them if a job is lost ■ the complexity of systems to navigate to access education, job-seeking assistance and financial entitlements ■ varying availability of effective vocational services, career advice and financial counselling, through which some of the above issues regarding support, disclosure, performance and finances might be addressed. Despite these barriers, it is increasingly recognized that addressing vocational aspirations serves to achieve key goals in supporting recovery (Slade 2009; Lloyd and Waghorn 2010); solutions to these issues are thus a priority. The provision of substitute work has a long history in psychiatry. Initially it was widely associated with the moral treatment methods of William and Samuel Tuke at The Retreat in York, and Philippe Pinel at Bicetre and La Salpetriere in Paris (see also Ch. 1). Substitute work subsequently became widespread in mental institutions, with people working in kitchens, laundries, gardens and workshops as part of their treatment. Their (often) unpaid labour also actively contributed to running these institutions (Wilcock 2001). Later, industrial therapy workshops provided substitute work in protected environments for those discharged from institutions. This practice that has declined for various reasons notably including that the working conditions were restrictive, with limited work choices, few opportunities for vocational development, and little access to mainstream employment (Schneider 2005). Current approaches have shifted towards supporting people to find and sustain mainstream employment of their own choosing, more in keeping with recovery-oriented practice and fostering self-determination (Slade 2009). This more directly tackles working conditions and practices that perpetuate employment disadvantage or exclusion, consistent with a social model of disability (Burchardt 2004). A focus on resources and support issues across individual, workplace and societal levels is essential to advancing knowledge and best practices for supporting work transitions (Kirsh et al. 2009; Shaw and Sumsion 2009). Supported employment refers to an approach where the primary goal is to secure employment in a mainstream setting, on an equivalent wage. It aims to help individuals find mainstream employment through rapid job search, job placement and on-the-job support, without lengthy prior prevocational assessment or training. Job searching and placement are tailored to individual preferences, with further support to retain employment (Bond et al. 2008). A further key characteristic for the success of supported employment programmes is the integration of vocational specialists into mental health teams, enabling vocational and mental health staff to regularly meet and interact formally and informally. These principles, originally defining Individual Placement and Support (IPS), are now considered more general principles for evidence-based supported employment (Bond 2004). Supported employment, based on IPS principles, has been extensively researched over the past two decades and substantial evidence supports its effectiveness for assisting people with persistent mental illnesses to get jobs, and promising outcomes for young people with psychoses (Bond et al. 2008; Waghorn and Lloyd 2010). Psychological interventions may be more often used to assist return-to-work of people with other conditions (Corbiere and Shen 2006; Harvey et al. 2009). However, research suggests that this approach has been less successful in assisting people to keep jobs. There are many ways of enhancing supported employment and potentially job outcomes, for example better job-matching processes, support for problem-solving, attention to work adjustments, natural supports in the workplace and employer education (Kirsh et al. 2005; Bond et al. 2008; Waghorn and Lloyd 2010). Qualitative studies involving people with mental health problems indicate helpful elements of ongoing support that might also include: support to develop personalized self-management strategies for maintaining one’s job and wellbeing; attending to disclosure and its consequences as an ongoing process in work settings; access to financial counselling and career advice; and opportunities for weighing the benefits and drawbacks of vocational options so as to make choices in an informed way (Johnson et al. 2009; Fossey and Harvey 2010; Blank et al. 2011). It is also recommended to have more involvement of people with expertise grounded in experience of mental ill-health and employment issues to further develop solutions and strategies that will improve career options and vocational success (Boeltzig et al. 2008; Shaw and Sumsion 2009). The success of supported employment in helping people get work has largely been based on securing entry-level job positions with limited opportunities for career development. Improving career pathways and options is one of the goals of supported education, an individualized approach based on similar principles to supported employment but focused on supporting people to access and successfully participate in educational courses of their choosing within mainstream settings (Murphy et al. 2005; Lloyd and Tse 2010). Supported education operates in a number of ways. For example, supports may be individualized to enable students to attend mainstream classes and to use on-campus learning supports available to all students. Alternatively, separate classes may be offered to accommodate the specific learning needs of people returning to study in educational settings. Since supported education provides a means to transition back into studies so as to gain qualifications, pursue personal development or vocational aspirations, and enhance employment options, it is also considered a promising approach to improve employment outcomes (Rudnick and Gover 2009; Lloyd and Tse 2010). To improve the vocational choices of people disadvantaged in the labour market, another approach is to actively promote the development of new employment options within communities (Krupa et al. 1998). Such initiatives include social firms and affirmative businesses that adopt a systemic economic development approach to create employment options, whereby working conditions that perpetuate employment disadvantage are eliminated (Krupa et al. 2003). These workplaces are designed with built-in adjustments that can make employment accessible, sustainable and support recovery for those who struggle, while offering equitable working conditions for all workers (Svanberg et al. 2010; Williams et al. 2010). Mental health services offer a unique work context for the employment of people with direct or lived experience of mental health issues. This expertise becomes a positive qualifying attribute or quality for work, rather than an experience to be hidden and not disclosed, for fear of discrimination. Individuals who choose to work in mental health services may do so to ‘put something back’; to ‘help others out in the same situation’; or to make a difference to services. However, a range of practices related to employment, human resources and organizational culture need to be in place to ensure safe, sustainable and equitable employment within the mental health workforce (Wolf et al. 2010). Further, self employment is an under-considered option, which can provide flexible, self-managed work that suits some people experiencing mental health issues (Hamlet Trust et al. 2007). Examples include people choosing to provide expertise as advocates, educators and researchers within the mental health sector on a consultancy basis, and people using their creative, artistic or other talents to develop their own businesses. Volunteering provides a potentially meaningful way to contribute to community life. Being a volunteer is valued socially and offers a positive role in contrast to that associated with being a mental health service user (Rebeiro and Allen 1998). Volunteering needs to be actively chosen to have these benefits. There are many avenues for volunteering that provide scope to explore interests (art, animals, conservation, spirituality, political activism and so on), as well as opportunities for personal development and social connections within one’s community. Peer support initiatives also often offer volunteering opportunities in settings among others who understand mental health issues. Volunteering may also support a sense of competence and accomplishment in a work-like environment that is supportive of staying well, without the perceived stressfulness of paid work, and enable exploration of potential interests and career options (Rebeiro and Allen 1998; Braveman 2012a). However, its effectiveness as a route to paid employment is less clear and it does not redress economic disadvantage, but may support recovery for those who choose and find meaning in volunteering as an occupation (Farrell and Bryant 2009). Services designed to facilitate service users’ involvement in volunteering as a means of vocational development are illustrated in Boxes 21-1 and 21-2.

Work and Vocational Pursuits

INTRODUCTION

WORK AND PRODUCTIVITY

UNEMPLOYMENT, EMPLOYMENT BARRIERS AND MENTAL ILL-HEALTH

BARRIERS TO VOCATIONAL OPTIONS AND EMPLOYMENT

ACCESS, OPPORTUNITIES AND SUPPORTS TO FIND AND SUSTAIN EMPLOYMENT

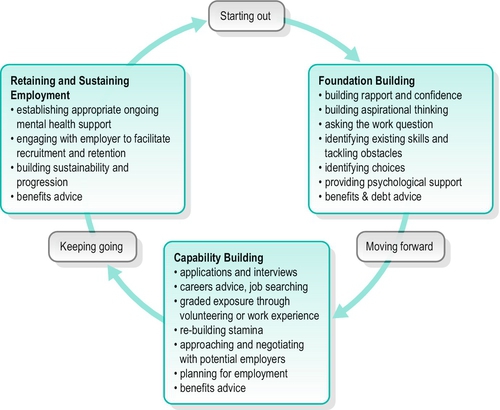

Employment Support

Supported Education

Creating New Employment Options

Volunteering

Neupsy Key

Fastest Neupsy Insight Engine