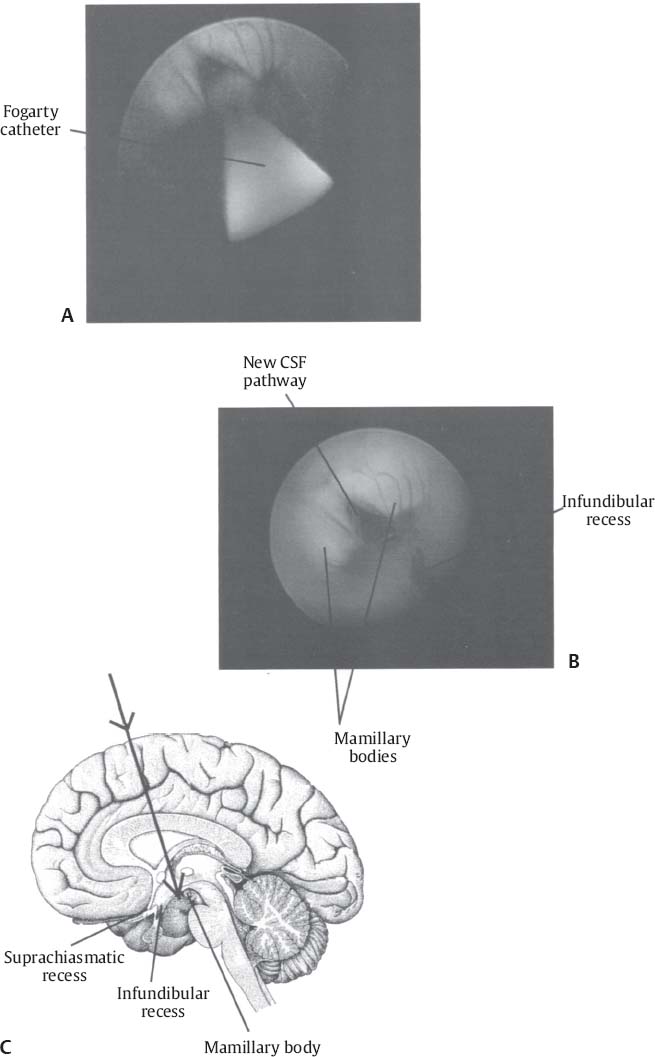

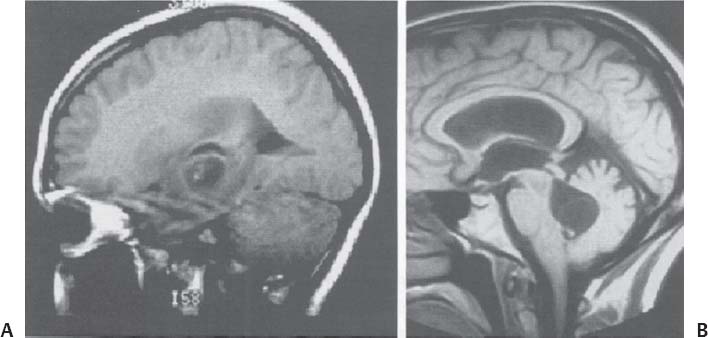

C H A P T E R 10 OTHER CRANIAL DISORDERS I. HYDROCEPHALUS (HCP) A. Evaluation 1. Occipitofrontal circumference 2. Computed tomography/magnetic resonance (CT/MRI) 3. Pump shunt 4. Shunt series—anteroposterior and lateral skull x-ray; chest and abdominal x-ray 5. Shunt-o-gram a. Radionucleotide b. 1 mL technetium injection while occluding distal tube c. Flush with 3 mL cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) d. Immediate abdominal image with gamma camera to rule out distal injection e. Image cranium to see proximal patency f. Image abdomen in 10 minutes B. Treatment 1. Shunts—ventriculoperitoneal, pleural, or atrial a. Frontal ventricular access i. 1 cm anterior to coronal suture and 3 cm lateral to midline b. Occipital ventricular access i. 7 cm above external occipital protuberance and 3 cm lateral to midline ii. Aim catheter toward 3 cm above nasion and insert 10 cm c. Ventriculoatrial placement i. Place occipital burr hole, sagittal incision over medial sternocleidomastoid ii. Tunnel between the two incisions, cut down 3 cm proximal to the neck incision iii. Pass atrial catheter, place ventricular catheter, perform internal jugular stick iv. Connect tubing after flushing 2. Third ventriculostomy—to treat aqueductal stenosis a. Foramen of Monro—must be 4.5 mm to fit endoscope b. Access—may be same location as for frontal ventricular catheter, but must check mid-saggital view for trajectory c. Penetrate floor of third ventricle anterior to mamillary bodies and posterior to infundibular and suprachiasmatic recesses d. Consider Bugby—Bovie catheter, #3 Fogarty balloon catheter, grasper, and irrigation (Fig. 10.1A–C). 3. Lumboperitoneal shunt—best used for pseudotumor cerebri; shown to increase risk of Chiari malformation in children (70%) 4. Emergent access to ventricles in the office setting—push down optic globe and insert spinal needle through roof of orbit in midpupillary line C. Complications 1. Malfunction rate—17% in first year; 50% in 5 years, usually by infection or obstruction Fig. 10.1 (A) Endoscopic view of the floor of the third ventricle with a Fogarty #4 catheter directed into the floor of the ventricle. (B) View after third ventriculocisternostomy. (C) Ventriculostomy anatomy diagram. (With permission from Citow JS. Neurosurgery Oral Board Review. 1st ed. New York, NY: Thieme Medical Publishers; 2003: 35, Fig. 5.1A–C.) 3. Subdural collections—treat by increasing the valve pressure, adding an antisiphon device, or shunting the subdural space to the peritoneum 4. Visual loss—after shunt placement or with hydrocephalus it may be from posterior cerebral artery (PCA) occlusion from downward herniation, papilledema, or an enlarged third ventricle compressing the optic chiasm. 5. Slit ventricle syndrome—may be due to overdrainage, intermittent underdrainage, or constant underdrainage 6. Positional headaches relieved by lying down—suggest overdrainage; treat with high valve pressure or antisiphon device 7. Nonpositional headaches—suggest shunt obstruction 8. Noncomplicant ventricles-ependyma scars and adheres to itself thus allowing increased pressure without a change in ventricular size 9. Shunt unable to be tapped—replace using the same trajectory and consider using an endoscope or image-guided assistance 10. Catheter adheres to choroid or ependyma—remove by inserting a stylet and coagulating with a Bovie D. Normal-pressure HCP 1. Signs/Symptoms—apraxic, wide-based gait, urinary incontinence, dementia (impaired memory, usually not severe) 2. Evaluation—CT/MRI and lumbar puncture (lumbar drain × 3 days at 10cc/hr and have physical therapy access for gait improvement) 3. Treatment—best results for shunting obtained in patients presenting with ataxia a. Urinary control improves first. b. 35% of patients develop subdural hematoma, so set value high and slowly titrate setting down II. MENINGITIS A. Neonates (<1 m)—group B strep and E. coli B. Newborns (1–3 m)—strep pneumonia C. Children (3–7 years)—H. influenza D. Older children and adults (>7 years)—N. meningitidis, Listeria E. Elderly—strep pneumonia F. Postop or wound infection—usually staph G. Chronic meningitis—usually tuberculosis, fungus, cysticercosis, tumor, or sarcoid III. SKULL OSTEOMYELITIS A. Treatment—3 months of antibiotics; replace bone in 6 months IV. BRAIN ABSCESS A. Causes—usually strep, fungus (immunocompromised), and gram-negative rods (infants). B. Evaluation—complete blood count (CBC), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), MRI, Gram stain, culture (also for fungus and AFB [acid fast bacillus]). C. Treatment 1. Antibiotics—6 weeks intravenous (IV) and 6 weeks orally (PO) 2. Surgery (to aspirate or excise)—in cases with abscess > 3 cm, unknown organism, location near the ventricle (80% mortality with rupture into ventricle), increased intracranial pressure (ICP), or failed antibiotic therapy a. Use anticonvulsants b. Antibiotics may be stopped 1 week after capsule is excised. c. Follow-up CTs at 2, 4, and 6 weeks during antibiotic therapy V. SUBDURAL EMPYEMA A. Causes—usually strep and related to recent surgery or adjacent infection B. Signs/Symptoms—caused by venous thrombosis and infarction C. Treatment—urgent craniectomy or burr-hole drainage VI. HERPES SIMPLEX VIRUS A. Signs/Symptoms—hemorrhagic inflammation of medial temporal lobes followed by rapid decline into coma B. Evaluation 1. MRI—edema 2. LP—increased lymphocytes and protein 3. Biopsy—if unsure of diagnosis; start IV acyclovir before biopsy 4. Polymerase chain reaction—usually returns too late to help C. Treatment—acyclovir VII. ACQUIRED IMMUNODEFICIENCY SYNDROME (AIDS)—focal lesions are due to toxoplasma, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), lymphoma, and cryptococcus. There may also be AIDS encephalitis and dementia. A. Toxoplasmosis 1. Evaluation—detected by a change in baseline titers 2. Treatment—pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine B. PML 1. Cause—JC virus (JCV) 2. Signs/Symptoms—presents with mental changes 3. Evaluation a. MRI with nonenhancing increased T2 signal b. Loss of myelin in the white matter c. LP may be sent for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for JCV. 4. Treatment—none 1. Evaluation—enhances on MRI and is usually near the third ventricle; LP for PCR for Epstein-Barr virus. 2. Treatment—radiation and steroids; survival is 3 months D. Brain masses 1. Treatment—antitoxoplasma medications for 2 weeks and biopsy if there is no decrease in size VIII. CREUTZFELDT-JAKOB DISEASE A. Cause—prion or slow virus B. Signs/Symptoms—dementia, ataxia, visual loss, and myoclonus C. Evaluation 1. MRI—hyperintense on T2 in basal ganglia 2. LP—rule out syphilis, may see increased protein 3. Electroencephalography (EEG)—periodic spikes 4. Biopsy—spongiform encephalitis with decreased cells and no inflammation, stain for protease-resistant protein. Sterilize biopsy equipment with steam and sodium hydroxide. D. Treatment—none; death usually within 1 year IX. LYME DISEASE A. Cause—Borrelia burgdorferi B. Signs/Symptoms—many symptoms, including bilateral 7th nerve dysfunction. Neurologic symptoms are usually preceded by erythema chronicum migrans rash. C. Evaluation—serum antibody titer D. Treatment—antibiotics X. CYSTICERCOSIS Fig. 10.2 Cysticercosis. (A) Noninfused sagittal T1-weighted magnetic resonance images demonstrate cystic lesions with a scolex in the left temporal lobe and (B) in the fourth ventricle. (With permission from Citow JS. Neuropathology and Neuroradiology: A Review. New York, NY: Thieme Medical Publishers; 2001: 30, Fig. 32.) A. Evaluation—serum or CSF enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) study and CT/MRI B. Treatment 1. Praziquantel or albendazole for 30 days 2. Ocular or spinal cysts—avoid antibiotics 3. Large or intraventricular lesions—consider surgical resection 4. Ventricular shunting—often required (Fig. 10.2A,B) Helpful Hints

10: OTHER CRANIAL DISORDERS

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree