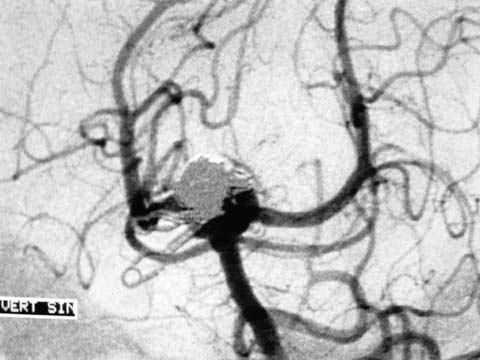

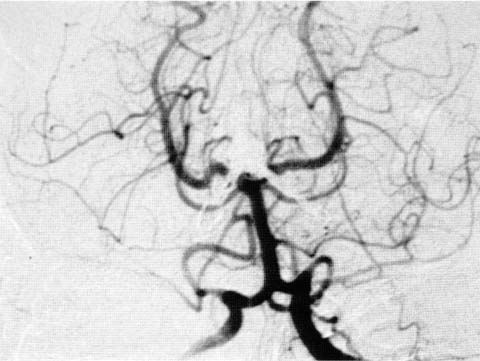

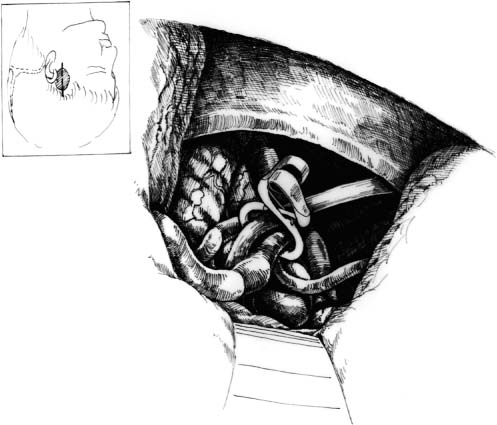

13 Diagnosis Multiple failures of endo- and exovascular surgery in total occlusion of a large-based, basilar bifurcation aneurysm Problems and Tactics Aneurysm bases left partially untreated are well known to cause recurrent growth of the aneurysm. Despite multiple operations, both exo- and endoarterially, a large part of the base of a ruptured basilar bifurcation aneurysm remained open. Scarring due to earlier operations and around clips outside the aneurysm on the right side, and coils inside the aneurysm made final total occlusion difficult. A left-sided subtemporal approach as advocated by Drake was chosen to treat the remaining base. Keywords Basilar bifurcation aneurysm, failed surgery, bring clip, subtemporal approach A 51-year-old female had her large-based, ruptured, basilar bifurcation aneurysm treated by coils on the first day after bleeding in 1996. One year later a recoiling was done due to increased filling of the aneurysm and base. Due to refilling, 1 year later a right-sided pterional craniotomy was done. The large base could be clipped partially with two clips by transsylvian route, but due to coils inside the aneurysm and perforators in the far corner it was not possible to occlude the whole base (Fig. 13–1). The remaining left-sided base was occluded by the left subtemporal approach in 1999 with total occlusion of the aneurysm and good clinical outcome of the patient (Figs. 13–2 and 13–3). In the park bench position, a left, small, subtemporal craniotomy through a linear incision was done. After incising the fascia and temporal muscle along its fibers upright to the arch, the muscle with its fascia was removed posteriorly from the temporal root of the zygoma. Anteriorly, both leaves of the temporal fascia were separated from the arch with blunt dissection so as not to injure the facial nerve. This allowed wide spreading of the temporal muscle with a curved retractor and fish hooks. A small bone flap sized 3 × 3 cm was done with one burrhole and craniotome, taking care not to injure the dura. After spinal drainage of 50 mL of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), the brain was slack after opening the dura in V- form, base downward, and after very careful fixation of the dura with stitches to the surrounding muscles or draping. Under the microscope, the brain was covered with oxidized cellulose and large wet cottonoids. The course of creating the operative route was like taking the temporal lobe in the retracting hand and pulling upward to see the tentorial edge. A broad Aesculap retractor was used so as not to cut inside the temporal lobe. The junction of the vein of Labbé with the lateral sinus was well posterior, as is ordinarily the case, and not in jeopardy in this approach. FIGURE 13–1 Preoperative (after two endoarterial and one right-sided transsylvian approach) vertebral artery angiography shows a broad-based, basilar bifurcation aneurysm partially filled with coils and partially clipped with two clips. As the uncus was raised with the tip of the retractor, the third nerve was elevated with it. The basilar bifurcation was high in relation to the posterior clinoid in this case, and it was necessary to separate the third nerve from the uncus and to work on both sides of it. The superior cerebellar artery and P1 were identified with the help of the third nerve and followed to the basilar artery. The position of the lateral aspect of the neck and waist of the aneurysm was then known as being just medial to P1, but covered by scarring and by the P1 perforators. Some parts of the coils were also seen. The posterior communicating artery was carefully preserved in the event some injury to the P1 occurred or if it became necessary to include the P1 in the clip. Only enough of the broad base was cleared anteriorly to accept the width of the clip blade. The major difficulties with this aneurysm lied behind the sac, as is usually the case. Clearing the base of the P1 prepared the way for finding and separating the perforators. Gentle retraction forward of the waist of the sac with the sucker tip was used to get behind the neck, and the perforators were cleared and separated from the aneurysmal base by using a small curved microdissector. The adherent perforators were separated upward far enough so that the posterior clip blade could slip inside them without kinking or tearing their origin. A ring clip (blade length 3 mm) was selected to close the open base, but it slipped away because of the coils and clips coming from the right side. The difficulty expected was that the coils inside the aneurysm would push the clip downward toward the basilar bifurcation to occlude it, and also that they might cause the wall to rupture if the pressure on the wall by the clip was too heavy. FIGURE 13–2 Postoperative vertebral artery angiography after the left subtemporal approach shows total occlusion of the aneurysm base with a ring clip. FIGURE 13–3 Schematic drawing shows the skin incision and small tic craniotomy, and the operative sketch after total occlusion of the aneurysm with a ring clip. With the fenestrated clip designed in 1969 by Drake, the P1

Subtemporal Approach to a Basilar Bifurcation Aneurysm with Failed Surgery

Clinical Presentation

Surgical Technique

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree