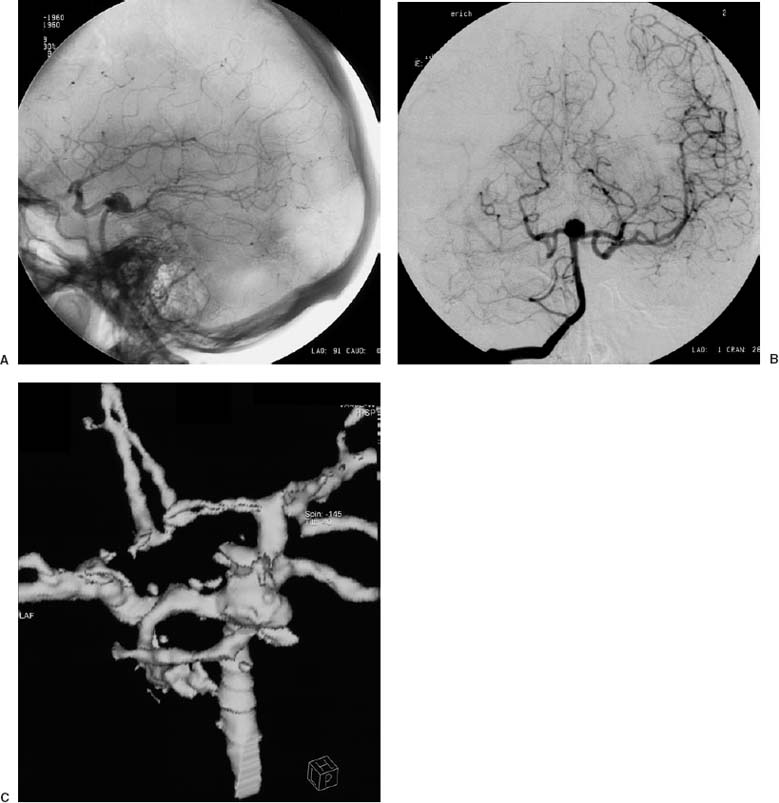

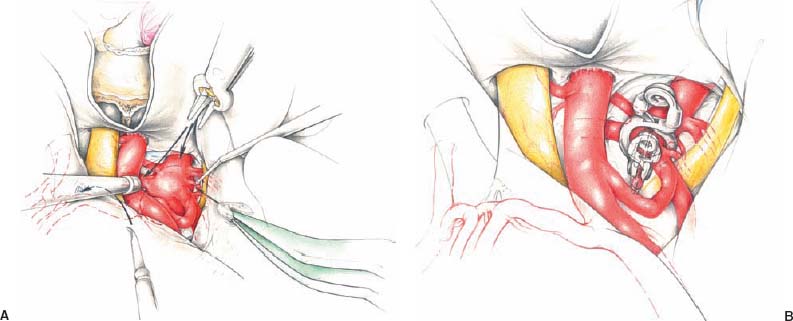

15 Diagnosis A backward-projecting, ruptured basilar bifurcation aneurysm associated with hypoplasia of the left internal carotid artery Problems and Tactics There were four preoperative angiographical findings of a ruptured basilar bifurcation aneurysm posing problems at the time of surgery: (1) There was backward projection of the aneurysm with its neck at the level of the posterior clinoid process (Fig. 15–1A). (2) The aneurysm was seen in combination with hypoplasia of the left internal carotid artery resulting in the entire left cerebral hemisphere being supplied vascularly from the vertebrobasilar circulation (Fig. 15–1B). (3) A fetal type of right posterior communicating artery was present. (4) The aneurysm had a broad neck so that both P1 segments were incorporated into the aneurysm neck at their proximal portion (Fig. 15–1C). Keywords Basilar bifurcation aneurysm, backward projection, hypoplasia of the internal carotid artery, extracranial-intracranial (EC-IC) bypass, selective anterior clinoidectomy This 42-year-old female suffered from a severe headache suddenly at night and was diagnosed on computed tomography (CT) as having a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). Cerebral angiography disclosed a basilar bifurcation aneurysm associated with the aforementioned problematic findings. The patient was operated on day 1 with an SAH of World Federation of Neurosurgeons Grading Scale (WFNS) Grade IV and Fisher 3. 1. A left-sided extracranial–intracranial (EC–IC) bypass was performed using a linear incision in the supine position, with the head turned to the right, as a primary surgical step before clipping of the aneurysm was undertaken. 2. Aneurysm clipping: The head was positioned and fixed in a Mayfield-Kees apparatus with the face turned to ~30 degrees to the left and the chin slightly turned upward. a. A pterional craniotomy on the right side was performed followed by flattening of the sphenoid ridge by drilling it away to the lateral corner of the superior orbital fissure. b. Opening of the dura and opening of the lamina terminalis for cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) drainage followed resulting in slackness of the brain. c. This was folllowed by an extradural selective anterior clinoidectomy, as has been described elsewhere.1 The clinoid process was removed en bloc. d. An additional dural incision toward the distal dural ring, at the lateral corner of the internal carotid artery, was made, enabling a wider working space and allowing for optimal illumination of the operating microscope. This enbabled better mobilization of the internal carotid artery. e. The basilar trunk was prepared by removing clots from around it within the retrocarotid space. For further dissection of the aneurysm a temporary clip to the basilar trunk was placed. This could be done with the removal of the anterior clinoid process and due to some distance of the basilar artery from the dorsum sellae in spite of the same level of the aneurysm neck and the posteior clinoid process seen on the lateral view of the angiography (Fig. 15–1A). FIGURE 15–1 Preoperative angiogram. (A) Lateral view of the vertebral artery: note the backward projection of the aneurysm with its neck just at the level of the posterior clinoid process. (B) Anteroposterior view of the right vertebral artery: the left middle cerebral artery is opacified via the strong left posterior communicating artery. (C) Three-dimensional computed tomographic angiography. Proximal portions of both P1 segments are incorporated into the aneurysm. FIGURE 15–2 Artist’s drawing. (A) Basilar bifurcation aneurysm projected backward after the anterior clinoidectomy: Small perforating branches are separated from the aneurysm wall by insertion of some small pieces of Tabotamp®. (B) The aneurysm was optimally occluded by use of a fenestrated clip in combination with an additional straight clip (see text). f. Another temporary clip was then placed to the left P1 from the opticocarotid triangle. Thus, the P1, the aneurysm dome over the basilar tip, and the area behind the basilar artery could be dissected safely by removal of the clot. Small perforating branches from the aneurysm neck and caudoproximal portion of the right P1 could thus be dissected from the aneurysmal dome. Haemostatic Tabotamp® (oxidated regenerated cellulose; Johnson & Johnson Intl) was inserted between the aneurysm dome and the basilar artery perforators (Fig. 15–2A). g. Dissection of the aneurysm neck was performed revealing the incorporation of the proximal portions of both P1 segments into the aneurysm neck. The absence of thalamoperforating arteries just in the vicinity of both the P1 and the aneurysm neck junction could thereafter be confirmed. Further dissection of the aneurysm at its cranial dome portion was abandoned because of the strong fetal-type posterior communicating artery, which was in the way. h. Application of a fenestrated clip was undertaken: One blade of the clip resided at the corner of the junctional portion of the P1

Backward-Projecting, Ruptured Basilar Bifurcation Aneurysm Combined with Hypoplasia of the Internal Carotid Artery

Clinical Presentation

Surgical Technique

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree