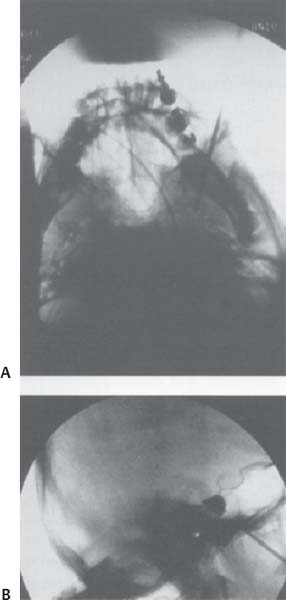

C H A P T E R 15 NEUROLOGY I. SEIZURE DISORDERS A. Evaluation—electrolytes (hypoglycemia, hyponatremia, hypocalcemia), complete blood cell count (CBC), computed tomography (CT), lumbar puncture (LP), toxicology screen, arterial blood gases (ABG), and electroencephalogram (EEG). B. Traumatic 1. Definition—early is <1 week after injury and late is >1 week. 2. Treatment—prophylactic anticonvulsants are used for only 1 week after traumatic hemorrhage if no seizure. Use for 3 weeks to 3 months if there is a cortical lesion; then perform EEG before tapering off over 2–4 weeks. C. Status Epilepticus 1. Signs/Symptoms—continuous seizures for >30 minutes or intermittent without a conscious interval; neurons may be damaged after 20 minutes of firing continuously. 2. Treatment—Ativan 0.1 mg/kg over 2 minutes (or Valium 0.2 mg/kg) and simultaneously load with Dilantin 20 mg/kg intravenously (IV) or phenobarbital 20 mg/kg IV (100 mg/min). If unsuccessful: 3. Consider general anesthesia [always use ABCs (airway, breathing, circulation)]; send for electrolytes, glucose, and ABG 4. Consider giving 50 mL of D50 or thiamine 100 mg IV D. Tonic-Clonic Seizures 1. Treatment—Dilantin, Tegretol, or phenobarbital E. Absence seizures 1. Treatment—ethosuximide or valproic acid F. Partial Complex Seizures 1. Treatment—Tegretol or Dilantin G. Antiepileptic Drug Side Effcts 1. Dilantin—nystagmus, ataxia, rash, gingival hypertrophy 2. Tegretol—ataxia, syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH), leukopenia, hepatitis (stop if γ-glutamyl transferase [GGT] 2× normal). 3. Keppra—thrombocytopenia H. Pregnancy 1. Folic acid—use in the first trimester to decrease birth defects 2. Anticonvulsants—increase the risk of congenital malformations; however, persistent seizures carry a higher risk I. Surgery—consider in a patient that has failed 1 year of multidrug therapy 1. Evaluation a. MRI—look for cortical dysplasia, tumor, or mesial temporal sclerosis b. Video EEG c. Positron emission tomography (PET) scan—localized hypometabolism ipsilateral to seizure focus in the postictal phase d. Wada test—assess dominant hemisphere language and memory function with large resection: intracarotid Amytal injection and angiogram to see cross-flow from dominant hemisphere; patient should have a flaccid arm for 5 minutes. e. Surgically implanted subdural surface grids—may be used to locate a focus. Avoid intraop benzodiazepines and barbiturates; use only narcotics and droperidol. Stimulate the cortex with 60 Hz frequency and 1 V for 2 msec. Taper the anticonvulsants preop and treat intraop seizures with phenobarbital 130 mg IV. 2. Resections a. Anterior temporal lobe—for mesial temporal sclerosis or local lesion b. Spare the superior temporal gyrus c. Incise the middle temporal gyrus to the temporal horn of the lateral ventricle; dissect over the hippocampus to incisura and choroidal fissure d. Stay subpial to preserve posterior cerebral artery (PCA) branches e. Resect 5 cm on the dominant side and 7 cm on the nondominant side f. Risks—vessel injury, Meyer loop injury (contralateral pie-in-sky field cut), and 3rd nerve injury near tentorium 3. Amygdalohippocampectomy 4. Discrete lesionectomy—cortical migration, tumor, or arteriovenous malformation (AVM) J. Disconnections—if seizures involve both hemispheres or are from an eloquent location 1. Corpus callosotomy—for drop attacks (atonic seizures) a. There is a 70% improvement in seizures. b. Cut only the anterior 1/3 of the corpus callosum to avoid disconnection syndrome (left tactile anomia and dyspraxia, right olfactory anomia and hand spatial problems, decreased spontaneous speech, and incontinence) c. Don’t cut the anterior commissure d. Consider Wada test for left-handed patients to avoid language and behavioral problems 2. Functional hemispherectomy—80% of patients improve a. Leave the basal ganglia intact. 3. Subpial transections—for partial complex seizures in eloquent cortex a. Cut every 5 mm to interrupt horizontal spread and leave vertical columns intact K. Vagal nerve stimulator—can decrease seizure frequency, but does not eliminate seizures; implant on the left side II. EEGMONITORING A. Helpful in the diagnosis of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD) and sub-acute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) B. Can determine burst suppression with barbiturates when used for cerebral ischemia C. Intraop reversal of somatosensory evoked potential (SSEP) wave helps to localize the motor—sensory strip junction. 1. An evoked potential decrease in amplitude of 50% or an increase in latency of 10% is considered significant, though there is much debate over how useful this is in surgery with tumor resection. III. DEMENTIA A. Treatable causes (20%)—medications, alcohol (ETOH), heavy metals, central nervous system (CNS) infection, hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, hyperglycemia, hypoglycemia, decreased parathyroid hormone (PTH), hypopituitarism, hyponatremia, Cushing disease, Wilson disease, uremia, porphyria, hydrocephalus, chronic subdural hematoma, tumor, hypertension (HTN), deficiency of vitamin B1 and B12 or folate B. Untreatable causes (80%)—Alzheimer disease (50%), multiinfarct dementia (15%), Pick disease, progressive supranuclear palsy (PSNP; Steele-Richardson-Olszewski syndrome), Parkinson disease, Huntington chorea, multiple sclerosis (MS), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), sarcoid, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), and CJD. C. Evaluation—CBC (infection or B12/folate deficiency with mean corpuscular volume MCV >100); electrolytes (glucose, Na+, BUN); thyroid; B12; folate; urine toxicity screen; electrocardiogram (ECG; AFIB with lacunes); chest x-ray (CXR), computed tomography (CT), lumbar puncture (LP), Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL). A. Cause—thiamin deficiency, usually in alcoholics B. Signs/Symptoms—confusion, conjugate gaze and lateral rectus palsies, nystagmus, and gait ataxia C. Evaluation—Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may detect inflammation and necrosis of the mamillary bodies, periventricular thalamus and hypothalamus, periaqueductal gray, floor of the fourth ventricle, and superior cerebellar vermis. D. Treatment—thiamine 100 mg IV followed by daily supplements and a normal diet E. Korsakoffpsychosis—a more chronic disorder with short-term memory loss and learning difficulties V. CREUTZFELDT-JAKOB DISEASE A. Cause—prion or slow virus B. Signs/Symptoms—dementia, ataxia, visual loss, and myoclonus C. Evaluation—MRI (hyperintense on T2 in basal ganglia), LP (rule out syphilis, may see increased protein), EEG (periodic spikes), and biopsy (spongiform encephalitis with decreased cells and no inflammation, stain for protease-resistant protein). D. Treatment—no treatment; death usually within 1 year E. Precaution—sterilize biopsy equipment with steam and sodium hydroxide. VI. PROGRESSIVE SUPRANUCLEAR PALSY—(PSNP; Steele-Richardson-Olszewski Syndrome) A. Cause—unknown, possibly autoimmune C. Evaluation—mainly clinical. MRI may show atrophy of the midbrain, superior colliculus, and subthalamic nuclei. D. Treatment—none VII. PARKINSONISM A. Cause—substantia nigra pars compacta degeneration producing decreased dopamine and increased acetylcholine (ACh) B. Signs/Symptoms—pill-roll tremor, cogwheel rigidity, bradykinesia, shuffle gait, and masked face C. Secondary Parkinsonism—olivopontocerebellar degeneration, Shy-Drager syndrome (autonomic dysfunction with orthostatic hypotension), progressive SNP (impaired vertical gaze, dysarthria, dysphagia, axial dystonia, emotional lability, survival 6 years), medically induced (Haldol, Compazine, Reglan), lacunes, and trauma D. Treatments 1. Dopamine agents—Sinemet with levodopa and carbidopa a. Dopamine does not cross the blood—brain barrier (BBB) but L-dopa does. b. Carbidopa (currently the most effctive agent) inhibits peripheral decarboxylation of L-dopa and is best for bradykinesia, but less effective for tremor. c. The major side effect is dyskinesia. 2. Dopamine agonists—bromocriptine (Parlodel) 3. Increase dopamine levels—Eldepryl (MAO-B inhibitor) and amanta-dine (dopamine agonist; inhibits reuptake) 4. Anticholinesterase—Benadryl (rarely used) 5. Fetal tissue implantation into substantia nigra—questionable benefit 6. Pallidotomy—radiofrequency (RF) lesion or stimulator to GPi or subthalamus a. Success rates—dyskinesia 90%, bradykinesia 85%, rigidity 75%, tremor 57% b. Also improves on/off symptoms c. Complications—visual field cut 3%, hemiparesis, dysarthria 8%, and speech and cognitive decline if bilateral lesions created 7. Thalamotomy—RF or stimulator to ventral intermediate thalamic nucleus (VIM) most effective for tremor VIII. ACUTE DISSEMINATED ENCEPHALOMYELITIS A. Cause—autoimmune, usually after a viral illness or vaccination B. Signs/Symptoms—monophasic deterioration with variable deficits that may include altered mentation, weakness, sensory loss, etc. C. Evaluation—MRI with hyperintense T2 plaque D. Treatment—steroids IX. MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS A. Cause—demyelination of white matter tracts in the CNS (especially periventricular) B. Signs/Symptoms—optic neuritis 50%, internuclear ophthalmoplegia (almost always indicates MS), motor, sensory, and genitourinary C. Evaluation—two attacks in Diffent places at Diffent times, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) oligoclonal bands of immunoglobulin G (IgG) with normal serum IgG, and protein <100, and MRI plaques (94% specific) D. Treatment—interferon beta-1b (Betaseron) injections decrease frequency of attacks by 30%; steroids are of unproven benefit. X. AMYOTROPHIC LATERAL SCLEROSIS B. Signs/Symptoms 1. Upper and lower motor neuron dysfunction 2. No cognitive, sensory, or autonomic dysfunction 3. Extraocular muscles and urinary sphincter usually spared 4. Tongue fasciculations common 5. Often lower motor neuron weakness in the legs with a normal MRI C. Evaluation—clinical and electromyogram (EMG; fibrillations) D. Survival—4 years E. Treatment—none XI. SUBACUTE COMBINED SYSTEMS DISEASE A. Cause—vitamin B12 deficiency, usually with malnutrition or pernicious anemia B. Signs/Symptoms—upper and lower motor neuron dysfunction (also may have peripheral neuropathy), impaired bilateral vibratory and touch sensation, and rarely mental or visual deterioration C. Evaluation 1. CBC to evaluate for macrocytic anemia (MCV >100) and hypersegmented polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) 2. MRI may reveal cervical and thoracic posterior and lateral column demyelination. 3. Other tests include B12 assay and serum methylmalonic acid and homocysteine. 4. Shilling test is used to evaluate for pernicious anemia. D. Treatment—B12 injections. Folic acid may correct anemia, but may worsen neurologic symptoms. A. Cause—autosomal recessive from chromosome 9 B. Signs /Symptoms 1. Gait ataxia, upper limb motor and sensory loss, and speech disturbances 2. Degeneration of axons and myelin in the posterior columns, corticospinal tracts, and spinocerebellar tracts 3. Degeneration of the cerebellum and brainstem nuclei 4. Motor neurons usually spared 5. Patients tend to have high-arched feet and pes cavus. C. Evaluation—clinical and MRI with cerebellar and spinal degeneration. D. Treatment—none. Patients are usually nonambulatory 5 years after onset (before 20 years of age) and die by mid-30s. XIII. ACUTE TRANSVERSE MYELITIS A. Cause—cell mediated immunity to CNS by infection, trauma, tumor, or toxin B. Signs/Symptoms—varied deficits, peaks at 2 days C. Evaluation—usually hyperintensity on T2-weighted MRI D. Treatment—steroids (unclear benefit). 50% of patients have a good recovery. XIV. GUILLAIN-BARRÉ SYNDROME A. Cause—possibly an antibody to peripheral myelin causing focal segmental demyelination with acute peripheral neuropathy B. Signs /Symptoms 1. Usually symmetric weakness, more proximal than distal 2. Little sensory involvement 3. Possible involvement of cranial nerves (CNs) 4. Possible autonomic dysfunction 5. Onset 3 days to 5 weeks after an upper respiratory infection, surgery, or immunization. Symptoms peak by 4 weeks with recovery over a few weeks after progression stops. C. Evaluation—CSF with increased protein and normal cells; nerve conduction velocity (NCV) with prolonged latencies D. Treatment—plasmapheresis, steroids (not proven helpful), and antibodies (unclear benefit) E. Diffentiate from 1. Acute intermittent porphyria—normal CSF protein, abdominal cramps, urine with δ-aminolevulinic acid 2. Lead poisoning—wristdrop, may be asymmetrical 3. Botulism—descending symmetrical bulbar paresis often with dilated pupils; normal NCV a. Cause—presynaptic impairment of ACh release b. Treatment—supportive by managing airway and circulation until toxin leaves system. Antitoxin may be used. XV. MYASTHENIA GRAVIS A. Cause—antibodies to nicotinic ACh-receptors on muscles B. Signs/Symptoms—intermittently weak (at end of day) with diplopia and ptosis in young females and older males C. Evaluation—CXR (15% have thymoma), collagen panel (other auto-immune diseases common), Tensilon test (edrophonium IV or neostigmine improves symptoms), EMG (decreased muscle action potential with repetitive nerve stimulation), and anti-ACh-receptor assay D. Treatment—anticholinesterase (pyridostigmine, consider decreasing muscarinic side effects with atropine), thymectomy (helps 80% of patients even without thymoma; there is frequent hyperplasia), plasmapheresis, azathioprine (immunosuppressant), and steroids XVI. EATON-LAMBERT (MYASTHENIC) SYNDROME A. Cause—antibodies to the presynaptic neuromuscular junction preventing ACh release B. Signs/Symptoms—symmetrical proximal pelvis and shoulder girdle weakness that improves with repetitive activity of the muscles; possible autonomic dysfunction C. Evaluation—search for primary neoplasm, especially pulmonary oat cell. Only 50% of patients have a known cancer at the time of diagnosis. EMG with incremental response D. Treatment—steroids and azathioprine (immunosuppression) XVII. PARANEOPLASTIC SYNDROME A. Cause—unknown, possibly autoimmune (anti-Yo, anti-Hu, etc.) B. Signs/Symptoms—variable with Diffent parts of CNS and PNS involved; may be acute or subacute and may be purely motor or sensory C. Evaluation—search for occult malignancy with CXR, etc. CSF to search for cytology and IgG D. Treatment—steroids XVIII. MENINGEAL CARCINOMATOSIS A. Cause—meningeal seeding by tumor cells B. Signs/Symptoms—headache, multiple cranial neuropathies, cerebrovascular assident (CVA), variable symptoms C. Evaluation—MRI with thickened enhancing leptomeninges; CSF with elevated protein and cells D. Treatment—steroids, but prognosis dismal XIX. POLYMYOSITIS A. Cause—autoimmune attack on muscles B. Signs/Symptoms—proximal symmetrical muscle weakness sparing ocular movements C. Evaluation—elevated creatine kinase (CK) and EMG with fibrillations. Rule out steroid myopathy, myasthenia gravis, hypothyroidism, and hyperparathyroidism D. Treatment—steroids XX. STEROID MYOPATHY—usually symmetrical proximal lower extremity weakness that resolves after steroid discontinued XXI. EPIDURAL LIPOMATOSIS A. Cause—accumulation of epidural fat compressing the thoracic or lumbar thecal sac, usually related to steroids or obesity B. Signs/Symptoms—back pain, lower extremity weakness, spasticity, sensory loss, and urinary retention or incontinence C. Evaluation—MRI D. Treatment—discontinue steroids, weight loss, and rarely laminectomy with resection of adipose tissue XXII. NEUROSARCOID A. Cause—unknown B. Signs/Symptoms—cranial neuropathy, hydrocephalus C. Evaluation—elevated serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (SACE) level 85%, CXR (hilar nodes), and skin biopsy with noncaseating granulomas D. Treatment—steroids; usually slow recovery XXIII. FIBROMUSCULAR DYSPLASIA A. Cause—unknown, but possibly a congenital medial defect B. Signs/Symptoms—headache, vertigo, transient ischemic attacks (TIAs); increased incidence of aneurysm (30%), tumor, and dissection 1. Angiogram 2. Second-most-common cause of ICA stenosis 3. 80% of cases are bilateral. 4. Most common site is the renal artery, followed by the cervical ICA D. Treatment—ASA, angioplasty, and resection with reconstruction (difficult) XXIV. SYNCOPE—transient loss of consciousness due to decreased cerebral blood flow A. Causes 1. Circulatory failure a. Impaired vasoconstriction (vasovagal response, postural hypotension, and primary autonomic insufficiency) b. Hypovolemia c. Decreased venous return (Valsalva maneuver, coughing, straining) d. Decreased cardiac output (dysrhythmia or obstructive) 2. Altered substrate delivery a. Hypoxia b. Anemia c. Hypoglycemia 3. Emotional disturbance B. Signs/Symptoms 1. Seizures causing sudden loss of consciousness 2. No prodrome, headache, or skin pallor changes 3. Syncopal episodes lack a postictal phase. A. Diffential—hemorrhage, pseudotumor cerebri, meningitis, venous sinus thrombosis, tumor, migraine, sinus disease, ear disease, dental disease, Tolosa-Hunt syndrome B. Innervation—there is no C1 sensory innervation. 1. Greater occipital nerve—from C2, 3 dorsal rami; provides sensation to the area rostral and medial behind the ear 2. Lesser occipital nerve—from C2 ventral ramus; provides sensation to the area caudal and lateral behind the ear 3. Posterior head—neck junction—innervated by the supraclavicular nerve from the C3, 4, 5 ventral and dorsal rami C. Migraine 1. Common—unilateral throbbing headache, nausea, vomiting, photo-phobia, and sometimes no aura of deficit 2. Classic—includes an aura of focal deficit <24 hour 3. Complicated—deficit may last up to 30 days 4. Migraine equivalent—focal deficit without headache a. Treatment (acute episode)—Compazine 10 mg IV, Toradol 30 mg IV, sumatriptan subcutaneously (SQ), caffeine/ergot 100 mg/1 mg 2 orally (PO). Ergots and triptans are vasoconstrictors. b. Prophylaxis—β-blockers (avoid in asthmatics), calcium-channel blockers, methysergide (serotonin agonist), control of HTN, and avoidance of oral contraceptive pills. 5. Other—There is frequently a family history of migraines. Children may present with an acute confusional state. D. Cluster headaches—unilateral oculofrontal or oculotemporal headaches with ipsilateral conjunctival injection, nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, lacrimation, partial Horner syndrome, agitation, and flushing (autonomic). Usually in males and last 30 to 90 minutes per day (at similar times) for 4 to 12 weeks with many months of remission 2. Prophylaxis—lithium 300 mg PO three times daily (t.i.d.) and methysergide E. Pseudotumor cerebri (benign intracranial hypotension)—increased intracranial pressure (ICP) and papilledema without a mass lesion and with a normal CT/MRI. Usually self-limited, though may cause blindness by optic atrophy. Occur most often in overweight females 1. Evaluation—MRI (there may be slit ventricles), LP (ICP >20 cm water), visual fields (enlarged blind spot and constricted visual fields), CBC, and collagen panel; be sure to rule out venous sinus thrombosis, sarcoid, and lupus erythematosus 2. Treatment—weight loss, diuretics (acetazolamide or Lasix), steroids, lumboperitoneal shunt (for headaches), or optic nerve sheath fenestration (for visual deterioration). F. Spontaneous intracranial hypotension—positional headaches exacerbated by standing. 1. Cause—possibly by a tear in a nerve root sleeve. 2. Signs/Symptoms—postural headache exacerbated by standing 3. Evaluation—MRI demonstrates meningeal enhancement. Consider myelography to locate leak. 4. Treatment—bedrest, hydration, Fioricet, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAIDS), and blood patch; similar to post-LP headaches and should be treated in a similar manner. XXVI. TEMPORAL ARTERITIS A. Cause—autoimmune disease B. Signs/Symptoms—headache, eye pain, visual loss (papilledema or optic atrophy, permanent blindness in 7%), jaw claudication C. Evaluation—elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) (50% have polymyalgia rheumatica with elevated CK) and biopsy (granulomatous skip lesions on external carotid artery (ECA) branches and ophthalmic arteries). XXVII. TRIGEMINAL NEURALGIA A. Rule out—atypical facial pain, V1 zoster, dental and orbital problems, temporal arteritis, and tumor B. Etiology—possibly due to ephaptic transmission of action potential C. Signs/Symptoms—lancinating, paroxysmal, sharp, electric, facial pain in a trigeminal distribution D. Evaluation—extraocular movements, facial sensation, corneal reflexes, jaw opening (pterygoid) and closing (masseter) E. Treatment 1. Pharmacologic—Tegretol 200 mg t.i.d. [up to 1600 mg/d, may cause confusion and lethargy, low WBC (keep >3000), SIADH, and elevated liver enzymes], baclofen, Neurontin, and Elavil. Narcotics usually not effective. 2. Surgical a. Destructive techniques—includes percutaneous balloon gangliolysis; (Fig. 15.1A,B), and glycerol or radiofrequency rhizotomy. The needle for percutaneous techniques is inserted 1 cm from the angle of the mouth, tunneled under the skin inside the cheek, aimed toward the foramen ovale under fluoroscopic guidance along the midpupillary line, and angled toward the zygoma 2 cm from the tragus. The needle should extend to the clivus–petrous ridge on lateral x-ray. Gamma knife radiosurgery is a new option that requires 2 to 6 weeks for improvement in pain. All of the procedures create new numbness as a trade-off for pain relief. b. Nondestructive technique—microvascular decompression. A vessel (usually by the superior cerebellar artery) compressing the trigeminal nerve is felt to cause emphatic transmission of painful impulses. A small retrosigmoid craniotomy is performed and the vessel is dissected offthe nerve which is then insulated with a Teflon pattie. A rare complication is hearing loss; so be sure the patient has contralateral hearing preoperatively. This technique is not usually useful for trigeminal neuralgia related to MS. Fig. 15.1 (A) Submental skull x-ray with needle in foramen ovale.(B) Lateral skull x-ray with inflated balloon showing characteristic “pear” shape. (With permission from Citow JS. Neurosurgery Oral Board Review. 1st ed. New York, NY: Thieme Medical Publishers; 2003: 23, Fig. 3.1A,B.) XXVIII. GLOSSOPHARYNGEAL NEURALGIA A. Signs/Symptoms—lancinating pain into the posterior throat or ear; afferent fibers from the carotid body to the dorsal X brainstem nucleus may cause the heart to stop with the pain. 1. Pharmacologic—similar to that for trigeminal neuralgia 2. Surgical—consists of craniotomy for microvascular decompression (posterior inferior cerebellar artery [PICA]) or sectioning CNs IX (above the arachnoid fold) and X (only upper two rootlets). XXIX. TRANSIENT GLOBAL AMNESIA A. Cause—may be related to migraine or vasospasm B. Signs/Symptoms—impaired recent and present memory in middle-aged persons; no other symptoms, benign course, seldom recurs XXX. MALIGNANT NEUROLEPTIC SYNDROME A. Causes 1. Blockage of dopamine receptors in the basal ganglia and hypothalamus after treatment with phenothiazines (Compazine or Thorazine) or Haldol 2. Possible dysfunction of the muscular sarcoplasmic reticulum 3. Possible autosomal dominance inheritance B. Signs/Symptoms—stupor, hyperthermia, hypotension, and rigidity C. Evaluation—hyperkalemia, myoglobinuria (may cause renal failure), elevated CK D. Treatment—bromocriptine (for CNS) and dantrolene (for muscles) XXXI. COMA A. Evaluation—electrolytes, CBC, ABG, urine toxicity screen, CT, LP (if CT normal) 1. Oculovestibular reflex (cold calorics)—do if the tympanic membrane is intact with head of bed (HOB) at 30 degrees. Irrigate 100 mL of ice water in one ear. In an awake patient there should be slow deviation ipsilaterally and the fast nystagmus component contralaterally [cold opposite and warm same (COWS)]. In a comatose patient with a normal brainstem, there should be conjugate ipsilateral deviation but no nystagmus because this requires cortical input. XXXII. BRAIN DEATH A. Signs/Symptoms—pupils fixed and dilated, absent corneal reflexes, oculocephalic reflexes (Doll’;s eyes), oculovestibular reflexes, gag flexes, and no movement of the body to a painful stimulus (the lower extremities may still have spinal-mediated withdrawal). B. Evaluation 1. Apnea test a. Requires pCO2 > 60 mm Hg without initiation of a breath b. Start with 15 minutes of 100% O2 and pCO2 40 c. Use passive O2 6 L/min during the test and wait 6 to 12 minutes while maintaining the pO2 > 80 2. Contributing factors to eliminate a. T >32.2°C (90°F) b. No intoxication c. Normal O2d. Systolic blood pressure (SBP) > 90 3. Reexamination—usually in 12 hours. For patients 1 year (1 day), 2 months (2 days), neonates (7 days) 4. Confirmation—usually not required. Consider EEG, cerebral blood flow (CBF; radionucleotide angiography), or test with atropine 1 mg (shouldn’;t affect heart rate because there will be no vagal tone). XXXIII. BRAINSTEM AND CORTICAL SYNDROMES Weber syndrome—CN III deficit with contralateral hemiplegia Benedikt syndrome—Weber’;s plus red nucleus lesion (ataxia and tremor of upper extremity) Millard—Gubler syndrome—CNs VI and VII deficit with contralateral hemiplegia Parinaud syndrome A. Signs /Symptoms 1. Decreased convergence, accommodation, and upward gaze (setting sun sign, supranuclear dysfunction) with normal vertical Doll’;s eyes 2. Possible lid retraction, usually caused by a pineal or quadrigeminal plate tumor or elevated ICP with the third ventricle pushing down upon the tectum 3. Diffential diagnosis of impaired ocular motility also includes Guillain-Barré syndrome, myasthenia gravis, botulism, Wernicke encephalopathy, and hypothyroidism. Foster-Kennedy’;s Syndrome—anosmia, ipsilateral optic atrophy, and contralateral papilledema, usually caused by an olfactory groove meningioma Dominant Parietal Lobe Lesion—Gerstmann syndrome with acalculia, agraphia (without alexia), right/left confusion, and finger agnosia Nondominant Parietal Lobe Lesion—dressing apraxia and neglect (may be from either side) Cortical Sensory Syndrome—decreased two-point discrimination, agraphesthesia (draw a number on the palm), and astereognosis (identify a coin in the hand) Alexia Without Agraphia—usually by a left posterior cerebral artery (PCA) stroke Prosopagnosia—due to a lesion in the bilateral or right medial parieto-occipital area XXXIV. SUPERIOR VERMIAN ATROPHY—trauma, Dilantin, ETOH XXXVI. ATONIC BLADDER—use urecholine to increase ACh. Evaluate with cystometrogram. XXXVII. SPASTIC BLADDER (HYPERREFLEXIC DETRUSOR)—use Ditropan to decrease ACh XXXVIII. REVERSIBLE POSTERIOR LEUKOENCEPHALOPATHY—demyelination of occipital lobes related to immunosuppression (cyclosporin), HTN, eclampsia. Usually resolves when the offending agent is withdrawn XXXIX. SELECTIVE VULNERABILITY TO HYPOXIA—hippocampus (CA1,3), parietooccipital cortex (layers 3,5), Purkinje cells, outer caudate, and putamen. Likely due to elevated glutamate levels XL. OPHTHALMOLOGY Monocular Blindness—consider amaurosis fugax, optic neuritis, retinal detachment Optic Neuritis—usually seen with MS (especially if bilateral) and sarcoid. A. Signs/Symptoms 1. Early stage—may appear as papilledema (blurred disk margins) 2. Later stage—may appear as optic atrophy (bright white optic disk with clean margins) Diabetic 3rd Nerve Palsy (Vasculitic/Ischemic)—pupil sparing and painful Compressive 3rd Nerve Palsy—pupil dilated early and painless Horner Syndrome—ptosis, miosis, and anhydrosis A. Sympathetic input to the head is through the superior cervical ganglion. B. Spontaneous causes—arterial dissection and tumor A. Cause—medial longitudinal fasciculus dysfunction B. Signs/Symptoms—contralateral medial rectus fails to move the eye medially to maintain conjugate gaze with the ipsilateral 6th nerve action (other 3rd nerve function is normal). C. Frequently associated with MS (especially if bilateral) or CVA Sixth Nerve Palsy A. Causes—elevated ICP, diabetes, cavernous sinus lesion, or Dorello canal inflammation B. Gradenigo syndrome—apical petrositis with sixth nerve palsy, V1-distribution retro-orbital pain, and a draining ear (due to infection) Painful Ophthalmoplegia A. Cause—often mucormycosis or diabetes B. Tolosa-Hunt syndrome—granulomatous inflammation of the cavernous sinus and superior orbital fissure Painless Ophthalmoplegia—consider myasthenia gravis Raeder’;s Paratrigeminal Neuralgia—partial Horner syndrome (no anhydrosis) with numbness in the trigeminal distribution Syphilis—causes near-light dissociation; pupil accommodates but does not react XLI. OTOLOGY Ménière Disease (Endolymphatic Hydrops) A. Signs/Symptoms—vertigo (5–30-minute episodes), emesis, tinnitus, and low-frequency hearing loss B. Evaluation—electronystagmography, audiogram, and MRI C. Treatment—salt restriction, diuretics, Valium, Antivert, avoidance of caffeine, 8th nerve sectioning, and shunting of the endolymphatic sac D. Rule out benign positional vertigo, vestibular schwannoma, and vestibular neuronitis Hearing Loss—use Rinne test to Diffentiate conductive versus sensorineural hearing Tinnitus—consider glomus jugulare, dural arteriovenous fistula (AVF), and cavernous–carotid fistula. Facial Palsy A. Causes—usually due to Bell palsy, trauma, zoster, or tumor. B. Treatment—repair with a direct anastomosis of XII, XI, or IX to VII Bell Palsy A. Cause—probably caused by a virus (usually herpes simplex virus [HSV], occasionally by Lyme disease). B. Treatment—steroids and eye protection (gold weight or tarsorrhaphy) C. Spontaneous recovery occurs in 80% (10% only partial); improvement begins in 3 weeks. Branches of the Facial Nerve (From Proximal to Distal)—to geniculate ganglion (lacrimation), stapedial (hyperacusis), chorda tympani (salivation, taste), and facial motor. Decreased Facial Sensation—consider hypocalcemia Helpful Hints

15: NEUROLOGY

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree