CHAPTER 19 Dementia

OVERVIEW

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV)1 criteria for dementia require a decline in memory (see Key Points), as well as an impairment of at least one other domain of higher cognitive function (e.g., aphasia [a difficulty with any aspect of language]; apraxia [the impaired ability to perform motor tasks despite intact motor function]; agnosia [an impairment in object recognition despite intact sensory function]; or executive dysfunction [such as difficulty in planning, organizing, sequencing, or abstracting]). Several important qualifiers (i.e., the condition must represent a change from baseline, social or occupational function must be significantly interfered with, the impairment does not occur exclusively during an episode of delirium, or cannot be accounted for by another Axis I disorder, such as major depression) are included in the definition.1

Many elderly adults complain of difficulties with their memory, often with learning new information or names, or finding words. In most circumstances, such lapses are normal. The term mild cognitive impairment (MCI) was coined to recognize an intermediate category between the normal cognitive losses that are associated with aging and with dementia. MCI is characterized by a notable decline in memory or other cognitive functions as compared with age-matched controls. MCI is common among the elderly, although estimates vary widely depending on the diagnostic criteria and assessment methods employed; some, but not all, individuals with MCI progress to dementia. The identification of those at risk for progression is an active area of research.2,3

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF DEMENTIA

The most common type of dementia (accounting for 50% to 70%) is Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Among the neurodegenerative dementias, Lewy body dementia is the next most common, followed by frontotemporal dementia (FTD). Vascular dementia (formerly known as multiinfarct dementia) can have a number of different etiologies; it can exist separately from AD, but the two frequently co-occur. Dementias associated with Parkinson’s disease and Creutzfeld-Jacob disease (CJD) are much less common.4

THE ROLE OF AGE OF ONSET

The onset of dementia is most common in the seventies and eighties, and is quite rare before age 40. Both the incidence (the number of new cases per year in the population) and the prevalence (the fraction of the population that has the disorder) rise steeply with age. This general pattern has been observed both for dementia overall, and for AD in particular. Estimates of the prevalence of dementia vary to some extent depending on which diagnostic criteria are used. The incidence of dementia of almost all types increases with age such that it may affect 15% of all individuals over age 65, and up to 45% of those over age 80.5 However, the peak age of onset varies somewhat among the dementias, with FTD and vascular dementia tending to begin earlier (e.g., in the sixties) and AD somewhat later.

EVALUATION OF THE PATIENT WITH SUSPECTED DEMENTIA

Establishing a precise etiology of dementia (Table 19-1) whenever possible allows for more focused treatment and for an accurate assessment of prognosis. Although reversible causes will be found in less than 15% of new cases, a diagnosis may help a patient and his or her family to understand what the future holds for them and to make appropriate personal, medical, and financial plans.

Table 19-1 Etiologies of Dementia

| Vascular |

| Stroke, chronic subdural hemorrhages, postanoxic injury, diffuse white matter disease |

| Infectious |

| Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, neurosyphilis, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PMLE), Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), tuberculosis (TB), sarcoidosis, Whipple’s disease |

| Neoplastic |

| Primary versus metastatic carcinoma, paraneoplastic syndrome |

| Degenerative |

| Alzheimer’s disease (AD), frontotemporal dementia (FTD), dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), Parkinson’s disease, progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), multisystem degeneration, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), corticobasal degeneration (CBD), multiple sclerosis (MS) |

| Inflammatory |

| Vasculitis |

| Endocrine |

| Hypothyroidism, adrenal insufficiency, Cushing’s syndrome, hypoparathyroidism/hyperparathyroidism, renal failure, liver failure |

| Metabolic |

| Thiamine deficiency (Wernicke’s encephalopathy), vitamin B12 deficiency, inherited enzyme defects |

| Toxins |

| Chronic alcoholism, drugs/medication effects, heavy metals, dialysis dementia (aluminum) |

| Trauma |

| Dementia pugilistica |

| Other |

| Normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH), obstructive hydrocephalus |

Up to one-third of cases of cognitive impairment may be at least partially caused by medication effects; common offenders include anticholinergics, antihypertensives, various psychotropics, sedative-hypnotics, and narcotics. Any drug is suspect if its first prescription and onset of symptoms are temporally related.

Psychiatric examination may reveal evidence of delirium, depression, or psychosis. On formal mental status testing, such as with the Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; see Table 2-8),6 and other cognitive tests (Table 19-2), documentation of particular findings, in addition to the overall score, allows cognitive functions to be followed over time.

Table 19-2 Supplemental Mental State Testing for Patients with Dementia

| Area | Test |

|---|---|

| Memory | Recall name and address: “John Brown, 42 Market Street, Chicago” |

| Recall three unusual words: “tulip, umbrella, fear” | |

| Language | Naming parts: “lab coat: lapel, sleeve, cuff; watch: band, face, crystal” |

| Complex commands: “Before pointing to the door, point to the ceiling” | |

| Word-list: “In one minute, name all the animals you can think of” | |

| Praxis | “Show me how you would slice a loaf of bread” |

| “Show me how you brush your teeth” | |

| Visuospatial | “Draw a clock face with numbers, and mark the hands to ten after eleven” |

| Abstraction | “How is an apple like a banana?” |

| “How is a canal different from a river?” | |

| Proverb interpretation |

Laboratory evaluation should include a complete blood count (CBC) and levels of vitamin B12 and folate, a sedimentation rate, electrolytes, glucose, homocysteine, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and creatinine, as well as tests of thyroid function and liver function (see Chapter 3). Screening for cholesterol and triglyceride levels is also useful. Syphilis serology is often included in an initial panel, but evidence of active infection is very rare. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain, without contrast, can also be useful in identifying a subdural hematoma, hydrocephalus, stroke, or tumor.

Additional studies are indicated if the initial workup is uninformative, if a particular diagnosis is suspected, or if the presentation is atypical (Table 19-3). Such investigations are particularly important in young patients with rapid progression of dementia or an unusual presentation. Neuropsychological testing may be quite useful, and is essential in cases where a patient’s deficits are mild or difficult to characterize. Briefer screening tools, such as the Folstein MMSE, have poor sensitivity and specificity for dementia, particularly in highly educated or intelligent patients. Such tests also generally fail to assess executive function and praxis.

Table 19-3 Supplemental Laboratory Investigations

| What | When | Why |

|---|---|---|

| Neuropsychological testing | Patient’s deficits are mild or difficult to characterize | The sensitivity of the MMSE for dementia is poor, particularly in highly educated or intelligent patients (who can compensate for deficits) |

| Lumbar puncture (including routine studies and cytology) | Known or suspected cancer, immunosuppression, suspected CNS infection or vasculitis, hydrocephalus by CT, rapid or atypical courses | Look for infection, elevated pressure, abnormal proteins |

| MRI with gadolinium; EEG | Any atypical findings on neurological examination; suspected toxic-metabolic encephalopathy, complex partial seizures, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) | More sensitive than CT for tumor, stroke Look for diffuse slowing (encephalopathy) vs. focal seizure activity |

| HIV testing | Risk factors or opportunistic infections | Up to 20% of patients with HIV infection develop dementia, although it is unusual for dementia to be the initial sign |

| Heavy metal screening, screening for Wilson’s disease or autoimmune disease | Suggested by history, physical examination, laboratory findings | May be reversible |

CNS, Central nervous system; CT, computed tomography; EEG, electroencephalogram; MMSE, Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

Brief Description

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive, irreversible brain disorder that robs those who have it of memory and overall mental and physical function; it eventually leads to death.7

Epidemiology of Alzheimer’s Disease

AD is the most common cause of dementia, affecting at least 4.5 million Americans. The incidence of the disorder is steadily increasing as the population ages, and by 2050 the prevalence may reach 14 million cases in the United States alone.8 Currently, AD is the seventh leading cause of death for adults, and the cost of care for patients with AD is now approximately $100 billion per year.9 Female gender carries an increased risk, even when accounting for differences in longevity, but some of the difference is offset by greater risk of vascular dementias in men. Vascular risk factors (except for male gender), including diabetes, atherosclerosis, hypertension, and elevated cholesterol, all increase the risk of AD, as well as of vascular dementia, although the mechanisms are unclear. A history of head trauma also increases the risk of AD. Putative protective environmental factors include greater educational attainment (a finding that holds even when possible biases associated with screening procedures are taken into account). Several pharmacological agents, notably postmenopausal estrogen supplementation, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and antioxidants, are associated with a decreased risk in epidemiological studies, but clinical trials of these agents have thus far been disappointing. More preliminary evidence links statins and H2 blockers to protection against AD. Mental and physical exercise have also been associated with prevention of AD, but there is a concern that these findings may be related to the impact of prodromal symptoms at baseline. However, as part of a comprehensive vascular risk reduction program, physical exercise has many benefits that may include dementia prevention.10

Pathophysiology

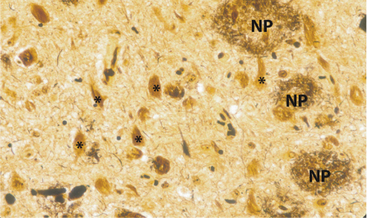

In his initial 1907 case, Alois Alzheimer identified abnormal nerve cells and fiber clusters in the cerebral cortex using then new silver-staining methods at autopsy. These findings, considered to be the hallmark neuropathological lesions of AD, are known as neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) and neuritic plaques (NPs) (Figure 19-1). Beta-amyloid protein, present in soluble form in the brain but also a major component of plaques, is thought to play a central pathophysiological role in the disease, perhaps via direct neurotoxicity.11 NFTs are found in neurons and are primarily composed of anomalous cytoskeletal proteins (such as hyperphosphorylated tau), which may also be toxic to neurons and contribute to AD pathophysiology.12–15

Genetics of Alzheimer’s Disease

In the context of genetic research, early-onset AD and late-onset AD are usually considered separately, divided by age of onset at 60 or sometimes 65 years. Early-onset AD is more likely to be familial; most autosomal dominant families have an early onset. However, late-onset AD also runs in families, and family and twin studies also support a role for genes in late-onset AD.16 These family and twin findings hold, despite controlling for the known late-onset AD gene APOE.

Four genes are recognized as being involved in AD. Three lead to early-onset AD in an autosomal dominant fashion. Although these genes have limited public health impact, they are devastating for affected families. These early-onset genes probably account for half of the cases of AD that occur before age 60. More critically, they have made a large contribution to our understanding of the pathophysiology of AD, and to the development of promising therapeutic strategies. Amyloid precursor protein (APP) on chromosome 21 was recognized first. To date, there are 26 mutations that affect 72 families. The age of onset for these APP mutations varies, and it is modified by APOE genotype. Next discovered was presenilin 1 (PSEN1) on chromosome 14. There are 156 PSEN1 mutations affecting 342 families to date; many have been found in a single family, often referred to as “genetically private.” PSEN1 mutations are associated with an age of onset in the forties and fifties; these mutations are not modified by the APOE genotype. Although overall quite rare, PSEN1 accounts for the great majority of autosomal dominant early-onset AD. PSEN1 mutations have also been observed in nonfamilial early-onset AD cases. The last early-onset gene is presenilin 2 (PSEN2) on chromosome 1. PSEN2 has 10 reported mutations affecting 18 families to date. The age of onset is quite variable, extending into the late-onset AD range, and it is modified by APOE genotype.17

The final AD gene is apolipoprotein E (APOE). Rather than a deterministic gene like the other three, APOE is a susceptibility gene that increases the risk for AD without causing the disease. APOE has three alleles, 2, 3, and 4, which have a complex relationship to risk for both AD and cardiovascular disease, with the 2 allele decreasing risk of both disorders and increasing longevity, and the 4 allele increasing risk and decreasing longevity. The effect of APOE-4 varies with age; it is most marked in the sixties, and falls substantially beyond age 80 or 90 years. APOE seems to act principally by modifying the age of onset, which is lowest in those with two copies of the risk allele, and intermediate in those with one. The APOE effect appears to be stronger in women and in Caucasians, which may relate to their lower risk of cardiovascular disease. Investigators believe that there are more AD genes to be discovered, and one analysis predicts 4 to 7 additional AD genes. However, these genes have been quite difficult to identify, and APOE remains the only documented late-onset AD gene.18

Patients frequently ask about their risk of AD based on their family history. Those with an autosomal dominant history are best referred for genetic counseling, ideally from an Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center or a local genetic counselor. Genetic testing is commercially available for PSEN1, which is likely to be involved when there is an autosomal dominant family history and the age of onset is 50 or lower. It can be used both for confirmation of diagnosis and for the prediction of disease onset, but there are complex logistical and ethical issues.19 Currently, genetic testing is only available for the remaining early-onset genes in research settings. Patients without such a history can be advised that there is an increased risk of AD in first-degree relatives. However, they should be made aware that this increase is modest and that age of onset tends to be correlated in families. Genetic testing for APOE can be used as an adjunct to diagnosis, but it contributes minimally. It is not recommended for the assessment of future risk because it lacks sufficient predictive value at the individual level. Many normal elderly carry an APOE-4 allele, and many AD patients do not.20

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

The typical clinical profile of AD is one of progressive memory loss. Other common cognitive clinical features include impairment of language, visuospatial ability, and executive function. Patients may be unaware of their cognitive deficits, but this is not uniformly the case. There may be evidence of forgetting conversations, having difficulty with household finances, being disoriented to time and place, and misplacing items frequently. At least two domains of cognitive impairment, including progressive memory decline (that affects functional ability), are required for a clinical diagnosis of AD.21 In addition to its cognitive features, a number of neuropsychiatric symptoms are common in AD, even in its mildest clinical phases.22 In particular, irritability, apathy, and depression are common early features, with psychosis (delusions and hallucinations) occurring more frequently later in the course of the disease.

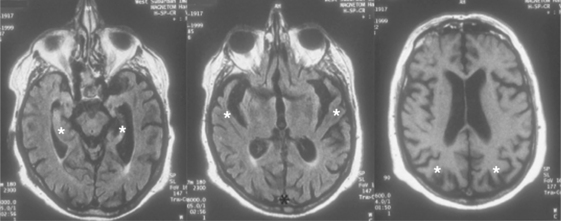

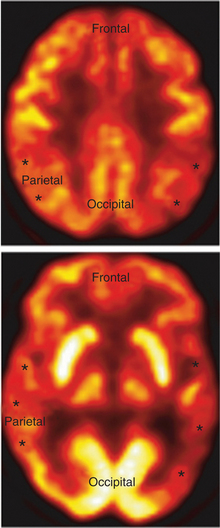

A definitive diagnosis of AD rests on postmortem findings of a specific distribution and number of its characteristic brain lesions (NFTs and NPs).23 Detailed clinical assessments (by psychiatry, neurology, and neuropsychology) in combination with structural and functional neuroimaging methods have a high concordance rate with autopsy-proven disease. Structural neuroimaging studies (such as MRI or CT) typically show atrophy in the medial temporal lobes, as well as in the parietal convexities bilaterally (Figure 19-2). Functional imaging studies of resting brain function or blood flow (i.e., positron emission tomography [PET] or single-photon emission computed tomography [SPECT]) display parietotemporal hypoperfusion or hypoactivity (Figure 19-3).

Differential Diagnosis

For AD, like other dementias, it is important to exclude potentially arrestable or reversible causes of cognitive dysfunction, or of other brain diseases that could manifest as a dementia (see Table 19-1). Beyond this, the key features are insidious onset, gradual progression, and a characteristic pattern of deficits, particularly early prominent deficits in short-term memory.

Treatments

Behavioral strategies, including environmental cues, such as reorientation to the environment with the addition of a clock and a calendar, can be reassuring to the patient. In addition, clear communication should be emphasized in this population, including keeping the content of communication simple and to the point, and speaking loud enough, given that decreased hearing acuity is common in the elderly. For those patients who are easily distressed or are psychotic, reassurance and distraction are strategies that can be calming.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree