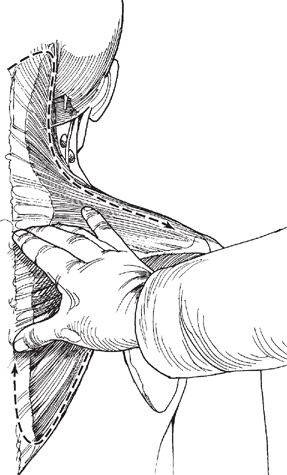

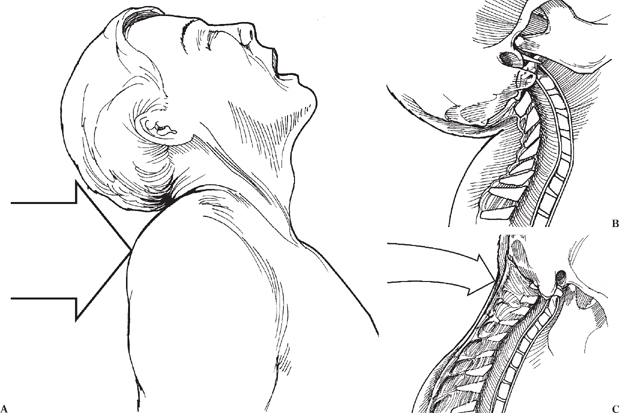

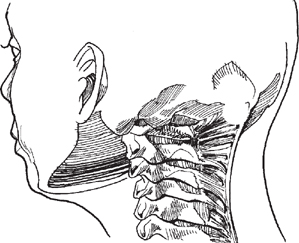

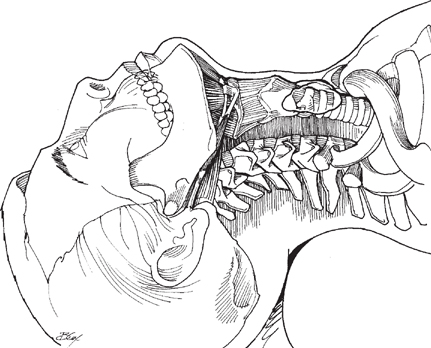

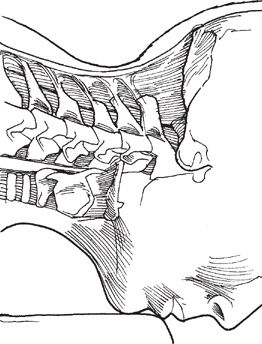

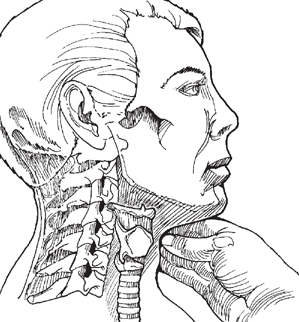

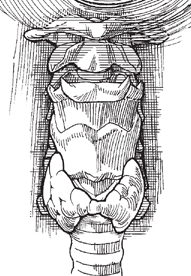

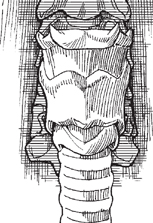

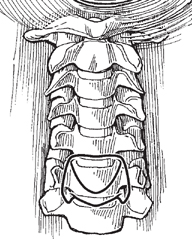

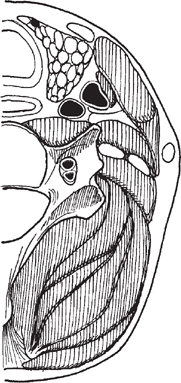

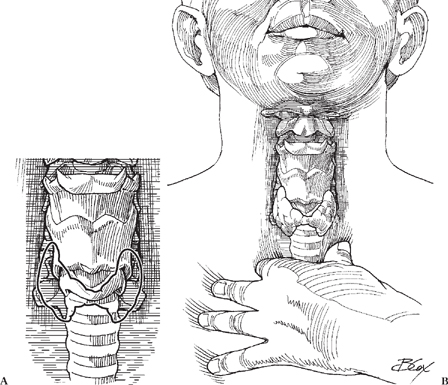

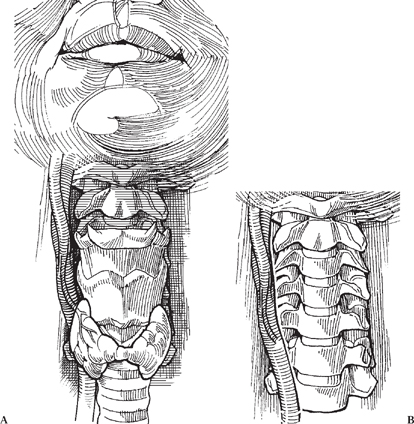

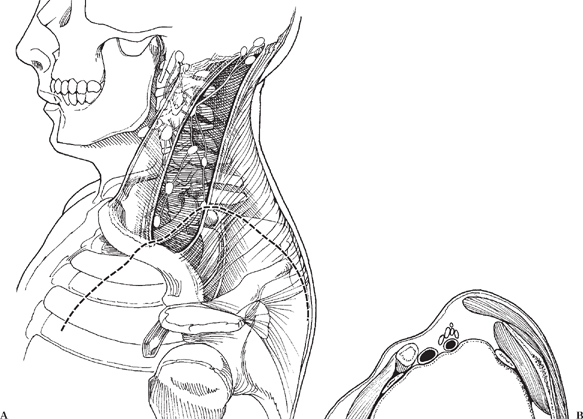

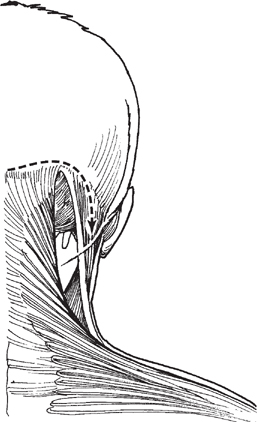

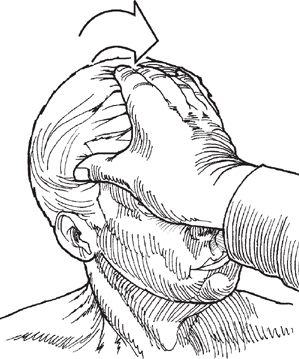

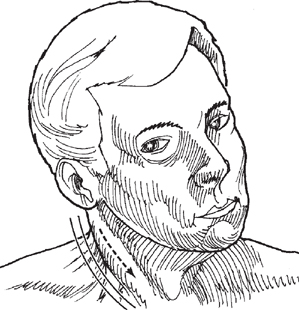

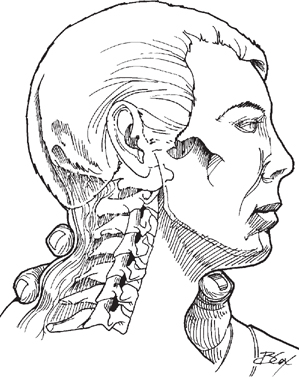

Chapter 2 CONTENTS II. CERVICAL SPINE MOTION TESTS The cervical spine exam is particularly important in patients with axial neck pain, arm pain, neurologic dysfunction of the upper or lower extremities, or bowel and/or bladder dysfunction. Because all of these symptoms can emanate from pathologies related to the cervical spine, spinal cord, or nerve roots, questions related to these types of symptoms should be posed while taking a history. Care should be taken to rule out myelopathy (signs/symptoms of spinal cord compression) to allow the patient an understanding of the risks associated with cervical spinal cord compression. If the patient has radicular complaints (pain, sensory changes, or weakness in a nerve root distribution), it behooves the examiner to try to delineate which nerve root is affected during the history and physical examination. Finally, always ask pertinent questions to help rule out a tumor or infection (night pain, fevers, chills, sweats, or unexplained weight loss). Visual Patient inspection starts when the patient enters the room. Observe the patient’s attitude. Note if the patient is in pain, irritated, angry, or frustrated, and if the complaint is a possible cause. Pay particular attention to see if the patient is protecting (splinting) any part of the body. Observe how the patient carries the head. Watch the patient, and note any kyphosis (hunch back), scoliosis (S-shaped curve), torticollis (twisted neck), difference in shoulder height, or other abnormalities. If the patient presents with an abnormality in posture, determine whether the patient can correct it without assistance. Be sure to note any pain. Try to deduce if the patient’s positioning could be causing the problem, and attempt to determine its relation to the patient’s complaint. Much can be learned from observing the patient undress. Motion of the head and neck normally should be smooth and fluid. Notice if the patient is limited in any motions or has trouble pulling the shirt over the head, unbuttoning buttons, or bending to take off shoes and socks. Note the patient’s range of motion and amount of pain. Once the patient is undressed, look for any signs of trauma, blisters, scars, discoloration, contusions, limb asymmetry, and atrophy. Palpation Before palpating, you may wish first to check for variation in skin temperature and for diaphoresis by comparing symptomatic with asymptotic areas using the back of the hand. Marked changes in temperature may indicate to the examiner areas where care should be taken not to cause unnecessary pain during palpation. Perform palpation systematically, using first bony and then soft tissue. In soft palpation, take note of tension and tenderness of the skin; the size, shape, and firmness of the muscles and any masses; and any other asymmetric differences found during the exam. Try to differentiate recent soft tissue changes that feel softer and more tender from older changes that will feel harder and more stringy. Also pay particular attention to the peripheral pulse: low pulse rate with low blood pressure could be the result of a sympathectomy from a spinal cord injury. Posterior Cervical Spine Soft tissue palpation should begin on the posterior aspect of the neck. It is best performed standing behind the patient with the patient seated (Fig. 2-1). Patients who are unable to sit may lie in a prone postion on the examination table. The examiner should stand facing the patient’s head. The posterior aspect of the cervical spine mainly consists of the trapezius, its associated lymph nodes, and the greater occipital nerve. Figure 2-1 Posterior view of the cervical spine, with bony and neural anatomy on the left (greater occipital nerve) and muscular anatomy on the right (trapezius muscle). Trapezius Origin: external occipital protuberance; medial one third of superior nuchal line; ligamentum nuchae; spinous processes from the seventh cervical to the twelfth thoracic vertebrae Insertion: lateral one third of the clavicle; acromion process; superior border and medial one third of the spine of the scapula Nerve supply: spinal accessory nerve [cranial nerve (CN) XI] and ventral rami of C3 and C4 Palpation of the trapezius starts bilaterally where the muscle is first located near its superior origin (Fig. 2-2). Find the muscle lateral and inferior to the inion, and palpate toward the acromion (Fig. 2-3). Feel for lymph nodes on the anterior aspect of the muscle. This chain of nodes is usually only palpable and tender from pathologic causes (infectious, tumorous, or viral). Once the acromion is reached, follow the lateral border of the muscle, palpating toward the spine of the scapula. Continue following the trapezius up along its origin on the spinal processes to the superior nuchal line. Figure 2-3 Continued palpation of the trapezius muscle at its origin on the spinous processes. Findings: Positive findings associated with the upper trapezius are frequently from flexion injuries as a result of whiplash. Tenderness in the area of the scapular spine insertion may also be indicative of a flexion injury of the cervical spine (Fig. 2-4). Tenderness here can also be related to disorders of the shoulder. Greater Occipital Nerve Palpation: Starting at the inion, bilaterally palpate for the greater occipital nerves. The greater occipital nerves are not normally palpable but can be sensitive. Findings: If the greater occipital nerves are palpable/hyperesthetic, it is probably because of inflammation as a result of a whiplash injury. Figure 2-4 (A-C) Whiplash injury. (B-C) Tenderness of the nuchal ligament can result from this injury. Palpation of nuchal ligament is helpful in identifying posttraumatic injury. Palpation: The superior nuchal ligament area is palpable in the midline from the inion to the C7 spinous process (Fig. 2-5). Findings: Generalized tenderness may indicate a stretch from a whiplash injury. Localized tenderness is not common in cervical spondylotic disease. Anterior Cervical Spine The anterior cervical spine is best palpated in the supine position (Fig. 2-6). Lay the patient on the examination table, and stand at the patient’s side. Place one hand under the patient’s neck for support, and use the other for palpation. Begin the examination with bony palpation, which consists of the hyoid bone, the thyroid cartilage, the first cricoid ring, the trachea, and the carotid tubercle. Follow this with soft tissue palpation, which consists of the sternocleidomastoid muscle with associated lymph nodes (looking for adenopathy), the carotid pulse, the parotid gland, and the supraclavicular fossa. Figure 2-5 Better delineation of this superior nuchal ligament originating on the inion and running in the midline attaching to the spinous processes. Figure 2-6 Position of the patient in extension for palpation of the anterior cervical spine. End palpation of the cervical spine with the patient in the prone position for bony palpation of the posterior head and neck (Fig. 2-7). The posterior bony palpation will include the occiput, the inion, the superior nuchal line, spinous processes of the cervical vertebrae, and the facet joints. Bony Palpation (FIG. 2-8) When palpating the bony structures, note any asymmetries, misalignments, lumps, abnormalities, and areas of tenderness. Hyoid bone The hyoid bone is a horseshoeshaped structure opening toward the spine. It is palpable by placing the thumb and index finger on each side of the neck, above the thyroid cartilage and below the mandible. Ask the patient to swallow, and feel for the hyoid bone as it elevates. Take care when palpating the hyoid bone because moderate pressure may cause it to break. The hyoid bone lies in a horizontal plane at the level of the C3 vertebral body. Figure 2-7 Patient in the prone position for bony palpation of the posterior head and neck. Figure 2-8 Bony structures of the neck. Figure 2-9 Beginning palpation for the thyroid cartilage by starting high in the neck. Thyroid Cartilage and Thyroid Gland Begin by locating the thyroid cartilage. Start high in the midline of the anterior neck, and palpate inferiorly until you feel its superior notch (Fig. 2-9). The prominent, superior portion of the thyroid cartilage, commonly known as the Adam’s apple (Fig. 2-10), lies in a horizontal plane with the C4 vertebral body. The inferior portion of the thyroid cartilage lies in a plane horizontal with the C5 vertebral body. Figure 2-10 Feeling the notch superiorly in the thyroid. Figure 2-11 Lateral and posterior to the thyroid cartilage is the thyroid gland. Figure 2-12 The first cricoid ring is located just below the thyroid cartilage. Figure 2-13 The carotid tubercle is found by moving laterally from the cricoid ring. Lateral and posterior to the thyroid cartilage is the thyroid gland (Fig. 2-11). Palpate the thyroid gland on both sides. A normal thyroid gland should be symmetric and smooth. If the gland feels cystic or lumpy, further work-up may be necessary to rule out disease of the thyroid. First Cricoid Ring The first cricoid ring is located just below the thyroid cartilage (Fig. 2-12). Ask the patient to swallow; this will cause the first cricoid ring to elevate and will make palpation easier. The first cricoid ring lies in a horizontal plane with the C6 vertebral body. Take care when palpating the cricoid cartilage; too much pressure may cause the patient to gag. Carotid Tubercle of C6 The carotid tubercle is found by moving laterally from the first cricoid ring (Fig. 2-13). Palpate the carotid tubercles one at a time. Bilateral palpation of the carotid tubercles may cause compression on both carotid arteries, causing the patient to faint (Fig. 2-14). Additionally, the depth of palpation necessary for this can be uncomfortable to the conscious patient. It is extremely useful to localize the C6 level when performing anterior cervical surgery. Figure 2-14 The carotid sheath lies directly anterior to the carotid tubercle. TRACHEA Evaluate the trachea (Fig. 2-15) for any deviation from the midline, and note any abnormal findings. Figure 2-15 (A) The trachea lies below the first cricoid ring and thyroid gland. (B) Palpation of the trachea. Soft Tissue Palpation of the Anterior Cervical Spine CAROTID PULSES The carotid pulses are palpable just lateral to the first cricoid ring and adjacent to the carotid tubercles (Fig. 2-16). The pulses are palpated one at a time to avoid restricting blood flow to the brain. The pulses should be of equal strength. Also feel for hematoma formation or thrills. Use the stethoscope at this point for auscultation. Figure 2-16 (A) Carotid artery branching showing internal and external divisions. (B) The carotid pulse is palpable just lateral to the first cricoid ring and adjacent to the carotid tubercles. SUPRACLAVICULAR FOSSA The supraclavicular fossa (Fig. 2-17) lies superior and posterior to the clavicle and lateral to the suprasternal notch. Look for any asymmetry, and palpate for any swelling or bulge. Findings: Enlarged lymph nodes and cervical ribs often present in the supraclavicular fossa. A large mass or asymmetry will need further investigation because of the possibility of a tumor. Figure 2-17 (A-B) Elements of the supraclavicular fossa. Sternocleidomastoid and Mastoid Process Origin: sternal head—anterior surface of the manubrium Clavicular head: superior surface of the medial one third of the clavicle Insertion: lateral surface of the mastoid process and lateral half of the superior nuchal line Nerve supply: spinal accessory nerve (CN XI) and ventral rami of C2 and C3 Palpation: Find the sternocleidomastoid muscle at its origin at the mastoid and follow it downward, palpating to its insertion on the clavicle. To find the mastoid process, start at the inion, and palpate laterally on the superior nuchal line until you feel its rounded process (Fig. 2-18). If the patient is able, have the person contralaterally rotate the head and ipsilaterally side bend the neck against resistance (Fig. 2-19). Figure 2-18 Finding the sternocleidomastoid at its origin at the mastoid is easiest by starting at the inion and palpating laterally on the superior nuchal line until you find the rounded process. Figure 2-19 If the patient is able, have the person rotate the head contralaterally while side bending against resistance. This will sometimes cause the patient’s sternocleidomastoid muscle to protrude (Fig. 2-20). Feel for the chain of lymph nodes that runs along the medial border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (Fig. 2-17). Findings: Torticollis is the turning of the head to one side because of injury to the sternocleidomastoid muscle. This may result from injury to the spinal accessory nerve, swelling, and/or protective spasm of the muscle, possibly due to stretch associated with a hyperextension injury of the neck, vertebral body disease, or tonsillar infection. Enlarged lymph nodes are a possible sign of infection in the upper respiratory tract. Parotid Gland Begin palpating the mandible at its union (Fig. 2-21). Follow it posteriorly back until you have reached the angle. The parotid gland lies over the angle of the mandible. If swollen, the angle of the mandible will not feel sharp. Figure 2-20 Protrusion of the sternocleidomastoid muscle seen with contralateral rotation and ipsilateral side bending of the neck. Figure 2-21 Palpation of the parotid gland at the angle of the mandible. Bony Tissue Palpation of the Posterior Cervical Spine The spinous processes are the most easily palpable bony structures in the spinal exam. Stand at the supine patient’s head. Place your thumb in the anterior midline and wrap your fingers around to the posterior aspect of the spine (Fig. 2-22). Starting high at the base of the skull, probe with your fingers until you find the first process, C2. Continue the exam caudally and end with T1. The spinous processes should lie in line with one another. Feel for misalignments and for any curvature other than the normal lordosis of the cervical spine. Note any pain, tenderness, or swelling in the paraspinal muscles. Facet Joints Begin by having the patient completely relax in the prone position. Start palpation of the facet joints by moving laterally on both sides of the C2 spinous process and feel for the facet joints between the vertebrae. Continue palpating to the C7-T1 facet joint and note any tenderness elicited from the examination. Figure 2-22 Palpation of the spinous processes, with the thumb in the anterior midline and the fingers wrapped around the posterior aspect of the spine. Active Motions Direct the patient to move the head in one of six directions and stop when the movement elicits pain or when the movement’s range has reached its limit. The goal of the active motion exam is to determine range of motion and pattern of movement. Positioning: The patient should stand or sit in a normal postural position. Observe the patient’s movements from behind or from the side. Flexion Instruct the patient to relax the jaw and bring the chin down as far as possible toward the manubrium without flexion of the thorax (Fig. 2-23). The patient should be able to touch the chin to the chest. Extension Instruct the patient to bring the head backward as far as possible without movement of the thoracic and lumbar spine (Fig. 2-24). As in flexion, instruct the patient to relax the jaw and leave it open to reduce tension of the platysma muscle. When the head is fully extended, the nose and forehead should be in a horizontal plane.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION OF THE CERVICAL SPINE

Chapter 2

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION OF THE CERVICAL SPINE

INSPECTION

CERVICAL SPINE MOTION TESTS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree