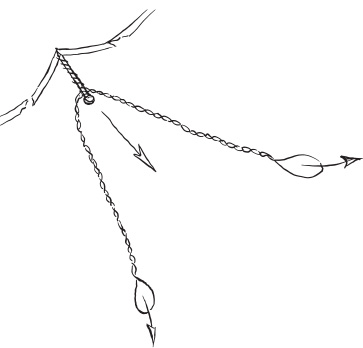

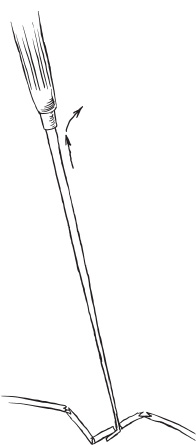

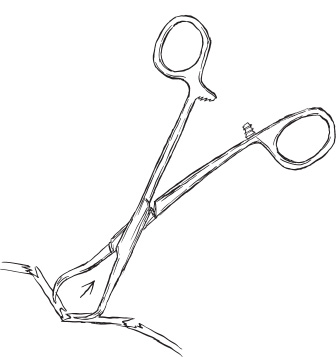

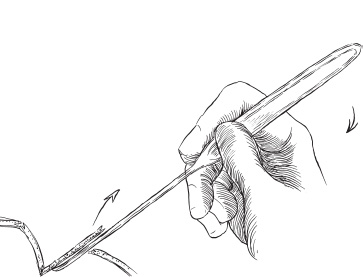

Trauma Twenty percent of children admitted to the hospital with head injury have a skull fracture. About 25% of skull fractures are depressed, and about 10% of those will be associated with dural laceration; 20% will be compound. The indications for elevation of depressed skull fracture have been discussed by Luerrsen and include cranial deformity, dural laceration, contamination, compression of the brain, and mass effect. Elevation of depressed fractures neither decreases the incidence of posttraumatic epilepsy nor substantially improves associated neurologic deficits. Principles of technique include adequate surgical exposure, decontamination, protection of the brain, and skin closure. Adequate exposure means a skin incision that allows ample working space to elevate the fracture. Small, chic incisions can lead to additional injury to the surrounding skin by power instruments, bone elevators, and retraction. Satisfactory decontamination includes the use of betadine or Hibiclens shampoo of the scalp and removal of all particulate matter. The time-honored neurosurgical technique of shaving the scalp has not proven efficacious. Shaving is time consuming, abrades and inoculates the skin with bacteria, and is not associated with a lower incidence of infection, although closing hairless skin is simpler, quicker, and requires less skill and patience. Sonic water irrigation and bacitracin irrigation solution are supplemented by intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis. The brain also must be protected from any additional injury caused by periosteal elevators. The heel of the curved Adson periosteal elevator can damage the underlying brain if used inappropriately in the dissection (see later discussion). Skin incisions generally incorporate any accompanying laceration unless the wound is a puncture. The hairline is always respected. S-shaped incisions allow wide exposure with self-retaining Gelpi retractors and facilitate extensive mobilization of the skin to close skin defects (see Goodrich). Wide undermining is essential in sliding the margins together; releasing the galea about 4 cm back from both edges of the incision can be useful. Three basic techniques are used to elevate the skull: dent pulling, craniotomy extraction, and prybar elevation. Each has its place in neurosurgical armamentaria. Dent pulling is a term taken from the automotive repair business. A screw is placed at the centerpoint of the depression. The screw is “noosed” with an 18-gauge wire, and upward pressure is exerted to elevate the fracture (Fig. 17–1). Alternatively, a small hole at the centerpoint of the depression gives purchase for a sturdy hook to be inserted, and the hook provides a good handle to pull up the fragments (Fig. 17–2). Another option is two obliquely drilled channels directed toward each other to allow a sharp towel clip to grip the fragment for extraction (Fig. 17–3). This technique is not well suited to depressions 1 cm or larger or more because the brain is too closely applied to the undersurface of the depressed bone to avoid injury. Simple or prybar elevation is best suited for depressions in neonates and infants (<1 year of age). A slot can be made in the bone at the margin (i.e., at the beginning of the slope) of the depression by a sharp, curved Adson elevator. Use controlled pressure downward and a side-to-side rocking motion similar to the action of the ancient tumi (Fig. 17–4). Alternatively, the edge of the depression can be rongeured away for a point of access. A straight Adson then is slipped through the slot, parallel to the surface of the dura, and edged carefully down the slope of the depression. If the diameter of the depression is short (<3 cm), a curved Adson works best; the tip of the curved Adson can be brought to bear near the deepest part of the depression and levered upward. Care is taken not to drop the heel or curve of the elevator on to the underlying brain. To erase the tissue memory of the depression, elevation of the fracture must be exaggerated and then allowed to settle into place. FIGURE 17–1. Dent pulling. FIGURE 17–2. Inserting a hook to pull up bone fragments. FIGURE 17–3. Two channels are drilled toward each other, and a sharp towel clip is inserted to grip the fragment for extraction.

DEPRESSED SKULL FRACTURES

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree