CHAPTER 3 Laboratory Tests and Diagnostic Procedures

A GENERAL APPROACH TO CHOOSING LABORATORY TESTS AND DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Diagnoses in psychiatry are primarily made by the identification of symptom patterns, that is, by clinical phenomenology, as outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR).1 In this light, the initial approach to psychiatric assessment consists of a thorough history, a comprehensive MSE, and a focused physical examination. Results in each of these arenas guide further testing. For example, historical data and a review of systems may reveal evidence of medical conditions, substance abuse, or a family history of heritable conditions (e.g., Huntington’s disease)—each of these considerations would lead down a distinct pathway of diagnostic evaluation. A MSE that uncovers new-onset psychosis or delirium opens up a broad differential diagnosis and numerous possible diagnostic studies from which to choose. Findings from a physical examination may provide key information that suggests a specific underlying pathophysiological mechanism and helps hone testing choices. Although routine screening for new-onset psychiatric illness is often done, consensus is lacking on which studies should be included in a screening battery. In current clinical practice, tests are ordered selectively with specific clinical situations steering this choice. While information obtained in the history, the physical examination, and the MSE is always the starting point, subsequent sections in this chapter address tests involved in the diagnostic evaluation of specific presentations in further detail.

ROUTINE SCREENING

Decisions regarding routine screening for new-onset psychiatric illness involve consideration of the ease of administration, the clinical implications of abnormal results, the sensitivity and specificity, and the cost of tests. Certain presentations (such as age of onset after age 40 years, a history of chronic medical illness, or the sudden onset or rapid progression of symptoms) are especially suggestive of a medical cause of psychiatric symptoms and should prompt administration of a screening battery of tests. In clinical practice, these tests often include the complete blood cell count (CBC); serum chemistries; urine and blood toxicology; levels of vitamin B12, folate, and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH); and rapid plasma reagent (RPR). Liver function tests (LFTs), urinalysis, and chest x-ray are often obtained, especially in patients at high risk for dysfunction in these organ systems or in the elderly. A pregnancy test is helpful in women of childbearing age, from both a diagnostic and treatment-guidance standpoint. Table 3-1 outlines the commonly used screening battery for new-onset psychiatric symptoms. The following sections will move from routine screening to a more tailored approach of choosing a diagnostic workup that is based on specific signs and symptoms and a plausible differential diagnosis.

Table 3-1 Commonly Used Screening Battery for New-Onset Psychiatric Symptoms

| Screening Tests |

| Complete blood count (CBC) Serum chemistry panel Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) Vitamin B12 level Folate level Syphilis serologies (e.g., rapid plasma reagent [RPR], Venereal Disease Research Laboratories [VDRL]) Toxicology (urine and serum) Urine or serum β-human chorionic gonadotropin (in women of childbearing age) Liver function tests (LFTs) |

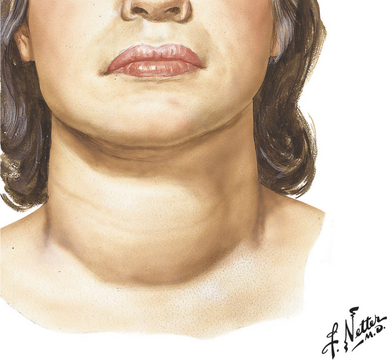

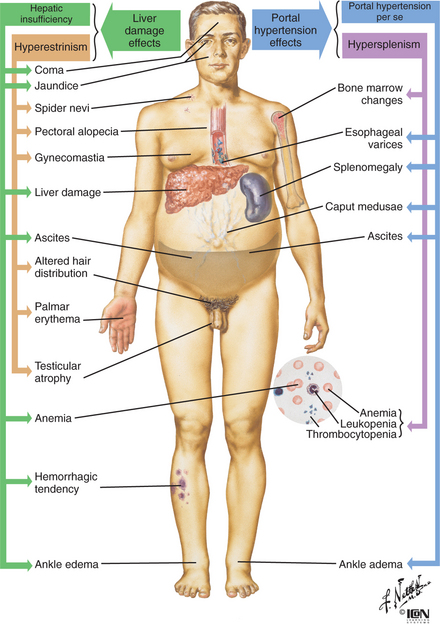

PSYCHOSIS AND DELIRIUM

New-onset psychosis or delirium merits a broad and systematic medical and neurological workup. Table 3-22 outlines the wide array of potential medical causes of such psychiatric symptoms. Some etiologies include infections (both systemic and in the central nervous system [CNS]), CNS lesions (e.g., stroke, traumatic bleed, or tumors), metabolic abnormalities, medication effects, intoxication or states of withdrawal, states of low perfusion or low oxygenation, seizures, and autoimmune illnesses. Given the potential morbidity (if not mortality) associated with many of these conditions, prompt diagnosis is essential. A comprehensive, yet efficient and tailored approach to a differential diagnosis involves starting with a thorough history, supplemented by both the physical examination and MSE. Particular attention should be paid to vital signs and examination of the neurological and cardiac systems. Table 3-33 provides an overview of selected physical findings associated with psychiatric symptoms. Based on the presence of such findings, the clinician then chooses appropriate follow-up studies to help confirm or refute the possible diagnoses. For example, tachycardia in the setting of a goiter suggests possible hyperthyroidism and prompts assessment of thyroid studies (Figure 3-1).4 On the other hand, tachycardia with diaphoresis, tremor, and palmar erythema, along with spider nevi, is suggestive of both alcohol withdrawal and stigmata of cirrhosis from chronic alcohol use (Figure 3-2).5 The astute clinician would treat for alcohol withdrawal and order laboratory tests (including LFTs, prothrombin time [PT]/international normalized ratio [INR], and possible abdominal imaging), in addition to the screening tests already outlined in Table 3-1. Neuroimaging is indicated in the event of neurological findings, although many would suggest that brain imaging is prudent in any case of new-onset psychosis or acute mental status change (without a clear cause). An EEG may help to diagnose seizures or provide a further clue to the diagnosis of a toxic or metabolic encephalopathy. A lumbar puncture (LP) is indicated (after ruling out an intracranial lesion or an increased intracerebral pressure) in a patient who has fever, headache, photophobia, or meningeal symptoms. Depending on the clinical circumstances, routine CSF studies (e.g., the appearance, opening pressure, cell counts, levels of protein and glucose, culture results, and a Gram stain), as well as specialized markers (e.g., antigens for herpes simplex virus, cryptococcus, and Lyme disease; a cytological examination for malignancy; and acid-fast staining for tuberculosis), should be ordered. A history of risky sexual behavior or of intravenous (IV) or intranasal drug use makes testing for infec-tion with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (with appropriate consent) and hepatitis C especially important. Based on clinical suspicion, other tests might include an antinuclear antibody (ANA) and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) for autoimmune diseases (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE], rheumatoid arthritis [RA]), ceruloplasmin (that is decreased in Wilson’s disease), and levels of serum heavy metals (e.g., mercury, lead, arsenic, and manganese). Table 3-46 provides an initial approach to the diagnostic workup of psychosis and delirium. Specific studies will be further discussed based on an organ-system approach to follow.

Table 3-2 Medical and Neurological Causes for Psychiatric Symptoms

| Metabolic | Hypernatremia/hyponatremia |

| Hypercalcemia/hypocalcemia | |

| Hyperglycemia/hypoglycemia | |

| Ketoacidosis | |

| Uremic encephalopathy | |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | |

| Hypoxemia | |

| Deficiency states (vitamin B12, folate, and thiamine) | |

| Acute intermittent porphyria | |

| Endocrine | Hyperthyroidism/hypothyroidism |

| Hyperparathyroidism/hypoparathyroidism | |

| Adrenal insufficiency (primary or secondary) | |

| Hypercortisolism | |

| Pituitary adenoma | |

| Panhypopituitarism | |

| Pheochromocytoma | |

| Infectious | HIV/AIDS |

| Meningitis | |

| Encephalitis | |

| Brain abscess | |

| Sepsis | |

| Urinary tract infection | |

| Lyme disease | |

| Neurosyphilis | |

| Tuberculosis | |

| Intoxication/withdrawal | Acute or chronic drug or alcohol intoxication/withdrawal |

| Medications (side effects, toxic levels, interactions) | |

| Heavy metals (lead, mercury, arsenic, manganese) | |

| Environmental toxins (e.g., carbon monoxide) | |

| Autoimmune | Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | |

| Vascular | Vasculitis |

| Cerebrovascular accident | |

| Multi-infarct dementia | |

| Hypertensive encephalopathy | |

| Neoplastic | Central nervous system tumors |

| Paraneoplastic syndromes | |

| Pancreatic and endocrine tumors | |

| Epilepsy | Postictal or intra-ictal states |

| Complex partial seizures | |

| Structural | Normal pressure hydrocephalus |

| Degenerative | Alzheimer’s disease |

| Parkinson’s disease | |

| Pick’s disease | |

| Huntington’s disease | |

| Wilson’s disease | |

| Demyelinating | Multiple sclerosis |

| Traumatic | Intracranial hemorrhage |

| Traumatic brain injury |

AIDS, Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Adapted from Roffman JL, Stern TA: Diagnostic rating scales and laboratory tests. In Stern TA, Fricchione GL, Cassem NH, et al, editors: Massachusetts General Hospital handbook of general hospital psychiatry, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2004, Mosby.

Table 3-3 Selected Findings on the Physical Examination Associated with Neuropsychiatric Manifestations

| Elements | Possible Examples |

|---|---|

| General Appearance | |

| Body habitus—thin | Eating disorders, nutritional deficiency states, cachexia of chronic illness |

| Body habitus—obese | Eating disorders, obstructive sleep apnea, metabolic syndrome (neuroleptic side effect) |

| Vital Signs | |

| Fever | Infection or neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) |

| Blood pressure or pulse abnormalities | Cardiovascular or cerebral perfusion dysfunction; intoxication or withdrawal states, thyroid disease |

| Tachypnea/low oxygen saturation | Hypoxemia |

| Skin | |

| Diaphoresis | Fever; alcohol, opiate, or benzodiazepine withdrawal |

| Dry, flushed | Anticholinergic toxicity |

| Pallor | Anemia |

| Unkempt hair or fingernails | Poor self-care or malnutrition |

| Scars | Previous trauma or self-injury |

| Track marks/abscesses | Intravenous drug use |

| Characteristic stigmata | Syphilis, cirrhosis, or self-mutilation |

| Bruises | Physical abuse, ataxia, traumatic brain injury |

| Cherry red skin and mucous membranes | Carbon monoxide poisoning |

| Goiter | Thyroid disease |

| Eyes | |

| Mydriasis | Opiate withdrawal, anticholinergic toxicity |

| Miosis | Opiate intoxication |

| Kayser-Fleisher pupillary rings | Wilson’s disease |

| Neurological | |

| Tremors, agitation, myoclonus | Delirium, withdrawal syndromes, parkinsonism |

| Presence of primitive reflexes (e.g., snout, glabellar, and grasp) | Dementia, frontal lobe dysfunction |

| Hyperactive deep-tendon reflexes | Alcohol or benzodiazepine withdrawal, delirium |

| Ophthalmoplegia | Wernicke’s encephalopathy, brainstem dysfunction, dystonic reaction |

| Papilledema | Increased intracranial pressure |

| Hypertonia, rigidity, catatonia, parkinsonism | Extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) of antipsychotics, NMS, organic causes of catatonia |

| Abnormal movements | Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, EPS |

| Gait disturbance | Normal pressure hydrocephalus, Huntington’s disease, Parkinson’s disease |

| Loss of position and vibratory sense | Vitamin B12 or thiamine deficiency |

| Kernig or Brudzinski sign | Meningitis |

Adapted from Smith FA, Querques J, Levenson JL, Stern TA: Psychiatric assessment and consultation. In Levenson JL, editor: The American Psychiatric Publishing textbook of psychosomatic medicine, Washington, DC, 2005, American Psychiatric Publishing.

Figure 3-1 Thyroid pathology in hyperthyroidism with diffuse goiter.

(Source: Netter Anatomy Illustration Collection, © Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.)

Figure 3-2 Gross features of cirrhosis of the liver.

(Source: From Netter Anatomy Illustration Collection, © Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.)

Table 3-4 Approach to the Evaluation of Psychosis and Delirium

| Screening Tests |

| Complete blood count (CBC) Serum chemistry panel Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) Vitamin B12 level Folate level Syphilis serologies Toxicology (urine and serum) Urine or serum β-human chorionic gonadotropin (in women of childbearing age) |

| Further Laboratory Tests Based on Clinical Suspicion |

| Liver function tests Calcium Phosphorus Magnesium Ammonia Ceruloplasmin Urinalysis Blood or urine cultures Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) test Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) Serum heavy metals Paraneoplastic studies |

| Other Diagnostic Studies Based on Clinical Suspicion |

| Lumbar puncture (cell count, appearance, opening pressure, Gram stain, culture, specialized markers) Electroencephalogram (EEG) Electrocardiogram (ECG) Chest x-ray Arterial blood gas |

| Neuroimaging |

| Computed tomography (CT) Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) Positron emission tomography (PET) |

Adapted from Smith FA: An approach to the use of laboratory tests. In Stern TA, editor: The ten-minute guide to psychiatric diagnosis and treatment, New York, 2005, Professional Publishing Group, Ltd, p 318.

ANXIETY DISORDERS

Medical conditions associated with new-onset anxiety are associated with a host of organ systems. For anxiety, as with other psychiatric symptoms, a late onset, a precipitous course, atypical symptoms, or a history of chronic medical illness raises the suspicion of a medical rather than a primary psychiatric etiology. Table 3-57 lists many of the potential medical etiologies for anxiety. These include cardiac disease (including myocardial infarction [MI] and mitral valve prolapse [MVP]); respiratory compromise (e.g., chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], asthma exacerbation, pulmonary embolism, pneumonia, and obstructive sleep apnea [OSA]); endocrine dysfunction (e.g., of the thyroid or parathyroid); neurological disorders (e.g., seizures or brain injury); or use or abuse of drugs and other substances. Less common causes (e.g., pheochromocytoma, acute intermittent porphyria, and hyperadrenalism) should be investigated if warranted by the clinical presentation. See Table 3-5 for the appropriate laboratory and diagnostic tests associated with each of these diagnoses.

Table 3-5 Medical Etiologies of Anxiety with Diagnostic Tests

| Condition | Screening Test |

|---|---|

| Metabolic | |

| Hypoglycemia | Serum glucose |

| Endocrine | |

| Thyroid dysfunction | Thyroid function tests |

| Parathyroid dysfunction | PTH, ionized calcium |

| Menopause | Estrogen, FSH |

| Hyperadrenalism | Dexamethasone suppression test or 24-hour urine cortisol |

| Intoxication/Withdrawal States | |

| Alcohol, drugs, medications | Urine/serum toxicology |

| Vital signs | |

| Specific drug levels | |

| Environmental toxins | Heavy metal screen |

| Carbon monoxide level | |

| Autoimmune | |

| Porphyria | Urine porphyrins |

| Pheochromocytoma | Urine vanillylmandelic acid (VMA) |

| Cardiac | |

| Myocardial infarction | ECG, troponin, CK-MB |

| Mitral valve prolapse | Cardiac ultrasound |

| Pulmonary | |

| COPD, asthma, pneumonia | Pulse oximetry, chest x-ray, pulmonary function tests |

| Sleep apnea | Pulse oximetry, polysomnography |

| Pulmonary embolism | D-dimer, V/Q scan, CT scan of chest |

| Epilepsy | |

| Seizure | EEG |

| Trauma | |

| Intracranial bleed, traumatic brain injury | CT, MRI of brain |

| Neuropsychiatric testing | |

CK-MB, Creatine phosphokinase-MB band; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CT, computed tomography; ECG, electrocardiogram; EEG, electroencephalogram; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PTH, parathyroid hormone; V/Q, ventilation/perfusion.

Adapted from Smith FA: An approach to the use of laboratory tests. In Stern TA, editor: The ten-minute guide to psychiatric diagnosis and treatment, New York, 2005, Professional Publishing Group, Ltd, p 319.

METABOLIC AND NUTRITIONAL

Myriad metabolic conditions and nutritional deficiencies are associated with psychiatric manifestations. Table 3-68 provides a list of metabolic tests with their pertinent findings associated with neuropsychiatric dysfunction. Metabolic encephalopathy should be considered in the event of abrupt changes in one’s mental status or level of consciousness. The laboratory workup of hepatic encephalopathy (which often manifests as delirium with asterixis) may reveal elevations in LFTs (e.g., aspartate aminotransferase [AST] and alanine aminotransferase [ALT]), bilirubin (direct and total), and ammonia. Likewise, the patient with uremic encephalopathy generally has an elevated blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine (consistent with renal failure). Acute intermittent porphyria (AIP) is a less common, yet still important, cause of neuropsychiatric symptoms (including anxiety, mood lability, insomnia, depression, and psychosis). This diagnosis should be considered in a patient who has psychiatric symptoms in conjunction with abdominal pain or neuropathy. When suggestive neurovisceral symptoms are present, concentration of urinary aminolevulinic acid (ALA), porphobilinogen (PBG), and porphyrin should be measured from a 24-hour urine collection. While normal excretion of ALA is less than 7 mg per 24 hours, during an attack of AIP urinary ALA excretion is markedly elevated (sometimes to more than 10 times the upper limit of normal) as are PBG levels. In severe cases, the urine looks like port wine when exposed to sunlight due to a high concentration of porphobilin.

Table 3-6 Metabolic and Hematological Tests Associated with Psychiatric Manifestations

| Test | Pertinent Findings |

|---|---|

| Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) | Increased in hepatitis, cirrhosis, liver metastasis |

| Decreased with pyridoxine (vitamin B6) deficiency | |

| Albumin | Increased with dehydration Decreased with malnutrition, hepatic failure, burns, multiple myeloma, carcinomas |

| Alkaline phosphatase | Increased with hyperparathyroidism, hepatic disease/metastases, heart failure, phenothiazine use Decreased with pernicious anemia (vitamin B12 deficiency) |

| Ammonia | Increased with hepatic encephalopathy/failure, gastrointestinal bleed, severe congestive heart failure (CHF) |

| Amylase | Increased with pancreatic disease/cancer |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (SGOT/AST) | Increased with hepatic disease, pancreatitis, alcohol abuse |

| Bicarbonate | Increased with psychogenic vomiting Decreased with hyperventilation, panic, anabolic steroid use |

| Bilirubin, total | Increased with hepatic, biliary, pancreatic disease |

| Bilirubin, direct | Increased with hepatic, biliary, pancreatic disease |

| Blood urea nitrogen | Increased with renal disease, dehydration, lethargy, delirium |

| Calcium | Increased with hyperparathyroidism, bone metastasis, mood disorders, psychosis Decreased with hypoparathyroidism, renal failure, depression, irritability |

| Carbon dioxide | Decreased with hyperventilation, panic, anabolic steroid abuse |

| Ceruloplasmin | Decreased with Wilson’s disease |

| Chloride | Decreased with psychogenic vomiting Increased with hyperventilation, panic |

| Complete blood count (CBC) | |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

| |